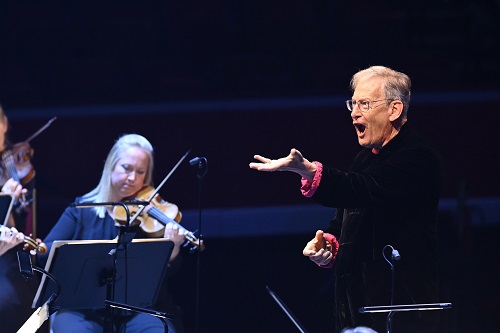

There’s no denying the energy and precision Sir John Eliot Gardiner can still coax from the Monteverdi Choir and English Baroque Soloists, founded by him over fifty years ago. In his 60th Promenade concert appearance there was vitality in abundance in a programme that focussed on the year 1707 when Bach and Handel were a couple of 22-year-olds. Their stylistic differences were artfully eclipsed in performances that highlighted a shared theatricality.

Lodged between Handel’s Donna, che in ciel and his virtuosic Dixit Dominus, Gardiner chose Bach’s Easter cantata Christ lag in Todes Banden (Christ lay in the fetters of death), revealing the latter’s own compositional virtuosity. Far from austere in its Protestantism, it’s an elaborate and dramatic setting of Martin Luther’s popular hymn, ‘Christ ist erstanden’. In his programme article Lindsay Kemp suggests the work may have been written to showcase his skills as part of an audition process for the post of organist at Mühlhausen. This marvellously detailed performance shone a light on Bach’s ingenuity, Gardiner articulating the work’s variation techniques with unfailing clarity and bringing into focus the expressive power of a text concerning man’s powerlessness over death, and the joy of the resurrection.

Indeed, references to Christ’s Easter rising in the first verse were made conspicuous by an emphatic delivery, the syncopated rhythms of the closing ‘hallelujahs’ sung with superb agility. There was tenderness in the soprano and alto duet (never originally conceived for solo voices), its pianissimo closing bars room-stilling in their intimacy. Thereafter, tutti tenors and later rich-toned basses made clear their unanimity of ensemble and clarity of diction, their energy and solemnity encapsulating a work that unequivocally declares Christ shall be our sustenance.

No less involving was Handel’s Marian cantata Donna, che in ciel, a work commemorating the fifth anniversary of an earthquake which shook the area around Rome, and which gives thanks to the Mother of God for averting disaster. No matter that Handel, a Lutheran, was setting a Catholic text; the composer takes every opportunity to assimilate Italian influences in a work scored for string band and alto soloist. Typically, Handel was to recycle some of its music for Agrippina and notably in the same year for Dixit.

Swedish mezzo soprano Ann Hallenberg was a suitably soothing protectress, wonderfully lissom in the coloratura writing of ‘Vacillò, per terror del primo errore’, strings enjoying the imitative writing and their thunderous effects. A decorative lute caught the ear in Hallenberg’s portrayal of Mary as a ‘serene star’, her melismas cherished if somewhat monochrome. Tuning was not always impeccable, but her voice found a natural outlet in the cantata’s operatic demands. Throughout, the English Baroque Soloists and their leader Kati Debretzeni were sensitive collaborators, along with the Monteverdi Choir which provided stylish support in the closing aria and chorus with the Virgin Mary’s assurances of peace and joy for the eternal city.

After the interval joy became unadulterated exuberance for the tour de force of vocal and instrumental writing that is Dixit Dominus, one of three Psalm settings Handel wrote in Rome for Cardinal Colonna. Its opening string passage burst upon us with an electricity that was as much do with Gardiner’s galvanising direction as the abandonment of social distancing on the platform. Then there was the choral force-field of 30-strong voices, unfailingly alert and crisp, at times pugnacious (‘Juravit Dominus’), and when delicate (the fiendish ‘Secundum ordinem Melchisedech’) possessing an intensity of delivery that was breath-taking. How could one not be enthralled by the disciplined attack at ‘Conquassabit’ or the fleet-footed sopranos who launched the beginning of the ‘Gloria Patri’? Singing as precision-engineered as this takes some beating.

Among the various soloists drawn from the body of the choir, Bethany Horak-Hallett and Dingle Yandell impressed in their respective alto and bass contributions, but it was Julia Doyle and Emily Owen whose singing crowned the evening. They sparkled in ‘Dominus a dextris tuis’ (with an ear-catching continuo team) and brought peerless musicianship to the melting suspensions of ‘De torrente’. Repeated as an encore, this duet was fabulously expressive and beautifully projected – an emotional highlight that held the audience spellbound.

David Truslove

The Monteverdi Choir and English Baroque Soloists: Handel – Donna, che in ciel; Dixit Dominus; J.S. Bach – Christ lag in Todes Banden BWV 4

Ann Hallenberg (mezzo-soprano), Julia Doyle and Emily Owen (sopranos), Bethany Horak-Hallett (alto), Graham Neal and Peter Davoren (tenors), Dingle Yandell (bass), Sir John Eliot Gardiner (conductor).

Royal Albert Hall, London; Wednesday 1st September 2021.

ABOVE: Ann Hallenberg with the Monteverdi Choir and English Baroque Soloists conducted by Sir John Eliot Gardiner (c) BBC/Chris Christodoulou