During the 17th century, daily religious observance was a regular feature at the French court. In the royal chapel Louis XIV was a habitual presence for Low Mass where custom sanctioned the performance of motets rather than settings of the Mass. Consequently, grands motets became the principal form of sacred music during Le Grand Siècle. With religious and ceremonial music offered regularly by the Musique du Roi, composers from Lully to Rameau responded to royal requirements with huge volumes of instrumental and choral music. Since Michel Richard Lalande (1657-1726) was responsible for providing and directing the music for the King over some forty years, it is no surprise that he left some seventy-seven Motets à grand chœur. Described by the 18th-century philosopher, writer and composer Jean Jacques Rousseau as ‘masterpieces of the genre’, these multi-sectional works were conceived for soloists, choir and instruments, and would become emblematic of the French Baroque, their texts chosen as much for specific liturgical occasions as to extol the piety and grandeur of the King.

As the favoured composer at the French court, effectively le grand fromage, Lalande brought the motet form to its height with performances becoming both a regular feature at court and, during the 18th century, a staple of the repertoire of Le Concert Spirituel. His music combines a wonderful mixture of nobility and joyousness with just enough toe tapping rhythm and melodic invention to keep a monarch from nodding off. And in these vibrant performances by Ensemble Correspondances under director Sebastian Daucé, there’s no danger of anyone catnapping. Voices are firm and characterful with colourful support from flutes, strings, plucked continuo instruments and organ. Added to that, interpretations sound freshly minted and incorporate plenty of stylish ornamentation, something which might conjure the frilly lace of Louis XIV.

Daucé champions three works by Lalande – Veni Creator (1684), Miserere (1687) and Dies Irae (1690) – which all belong to the early period of his career written between his appointment to the Chapelle Royale and his accession to the no less prestigious post of Surintendant de la Musique de la Chambre. Proceedings open with the Latin sequence Dies irae – composed for the funeral of the Dauphine Marie-Anne-Christine of Bavaria. Befitting a woman of royal connections, Lalande responds to the text with resplendent music, eliciting richly communicative performances from Ensemble Correspondances. Nowhere more heartfelt are the pleas on behalf of the Dauphine for eternal rest than in the long-limbed phrases and ravishing suspensions of the closing ‘Pie Jesu’. Earlier, intimations of the last judgment are superbly evoked by bass Etienne Bazola and concitato strings in the ‘tuba mirum’ and Perrine Devillers brings rapture to ‘Ora supplex at acclinis’.

Lalande’s Miserere is a setting of Psalm 50 (51) and would have been intended for performance during Holy Week. Lasting just under 35 minutes and following a format of alternating solos and choruses, its sombre beauty unfolds to reveal a judicious variety of sonorities, tempi and vocal weight. A soprano and alto duet brings charm to ‘Quoniam iniquitatem meam’ as the soloists acknowledge their transgressions, while a bass soloist and then a lively chorus adds to the accumulating drama of ‘Tibi solo peccavi’. Two ‘cleansing’ flutes anchored by a ground bass support a pure-voiced soprano in ‘Asperges me hysopo’, while an appropriate contrition underpins the ‘Sacrificium Deo’, the whole sung and played with considerable polish.

No less refined is the performance of Veni Creator, a work conceived for Pentecost, but also envisaged for ceremonies held on New Year’s Day and at Candlemas. This is reflected in its lively character which is heard to energetic effect in the dramatic ‘Gloria patri’, the choral writing now more virtuosic in the rapid scale figures and quick-fire exchanges. Instrumental playing is equally animated, the work set in motion with plenty of gutsy string playing and later a flatulent bassoon enlivens ‘Hostem repellas longius’ where a dialogue between solo and tutti groups endeavours to pursue the path of righteousness. Equally appealing is the tenor duet where the repetition at ‘Credamus omni tempore’ draws our attention to the everlasting spirit of the Almighty and his majesty.

Two items give opportunities for the instrumentalists alone, both works derived from Lalande’s Symphonies pour les Soupers du Roi. The first is a brief Quatuor and then, by way of a bonus track on the digital recording, a more substantial Grande pièce en G-ré-sol of alternating fast-slow movements with much variety of mood and timbre. Altogether, a fine disc, excellent notes and bright recorded sound.

David Truslove

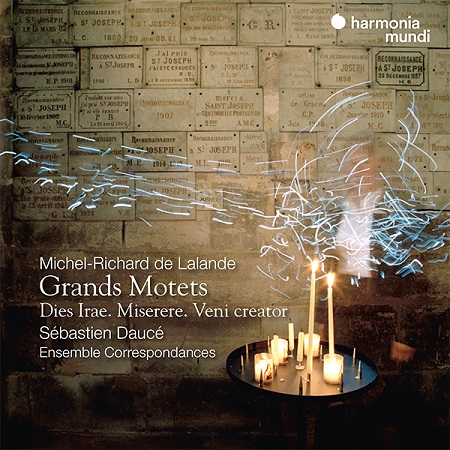

Michel-Richard de Lalande – Dies irae (S14), Miserere (S27), Veni creator (S31), Quatuor (extrait du 3e Caprice, ca 1713, des Symphonies pour les Soupers du roi), Grande pièce en G-ré-sol (digital version only).

Ensemble Correspondances, Sebastian Daucé (director)

harmonia mundi HMM 902625 [80.20]