And

happily, unlike Waters’ film, this production scored all the right points

for compelling dramatic relevancy.

The world’s most famous libertine (pace, Bill Clinton) is after all a

sexual compulsive in need of a Twelve Step Program. Director Robert

Tannenbaum has chosen to place heavy (though not heavy-handed) emphasis on

the title character’s wanton and unfulfilling abuses of his prodigious

sexual powers. Mr. Tannenbaum can always be counted on for a fresh and

inventive, yet honest interpretation. True, he can perpetrate the odd moment

here and there that doesn’t quite click; but mostly I find that he excels

at telling the story, presenting the character relationships that the authors

created, and staying out of the way of the music.

Indeed, the only character in this modern dress, minimalist production

that is not presented as a sexually active being with a gnawing appetite, is

the “Commendatore” The “Don” first appears in pantomime during the

overture, disguised as a cleric who seduces “Anna” from her evening

prayers in the chapel. She capitulates to his attentions quite willingly and

is soon pinned against the wall, writhing in increasingly pleasurable

foreplay until interrupted by daddy.

“Elvira” is presented as compulsive about all things: she reveals, and

consumes a chocolate cake during “Mi tradi”; tipples wine immodestly from

a bottle through much of the rest; and lengthily swaps some serious spit with

a “Leporello” who appears quite happy to have his tonsils cleaned by his

master’s sloppy seconds.

“Ottavio,” usually a cipher, was here a troubled divinity student who

was very receptive to having an intimacy-starved “Anna” remove his Roman

collar, and tear his cassock open to nuzzle his heaving bare chest during the

allegro section of “Non mi dir.”

And the young and shallow Love Couple, “Zerlina” and “Masetto,”

(mis-)behave like feckless horny wedding peasants from Nutley, New Jersey

sporting the best polyester wedding apparel that money can rent. His coral

prom tuxedo with ruffled shirt was just one of the many witty and telling

costumes by Ute Fruehling.

Peter Werner’s wholly effective modern setting consisted of a series of

high walls joined at disparate angles, creating a central hallway of sorts,

mounted on a turntable, and trimmed in with walls as matching legs. The

neutral textured ecru was an ideal surface upon which to project endless

lines of countless names of “Giovanni’s” conquests, the image varying

in intensity and legibility from scene to scene. No one was credited with the

wonderful lighting design which alternately used isolated areas and

spotlights, and mood- enhancing washes with excellent results.

Diana Tomsche (Zerlina), Mika Kares (Masetto), Konstantin Gorny (Don Giovanni), Christina Niessen (Donna Elvira), Ina Schlingensiepen (Donna Anna) and Bernhard Berchtold (Don Ottavio) [Photo: Jacqueline Krause-Burberg]

Diana Tomsche (Zerlina), Mika Kares (Masetto), Konstantin Gorny (Don Giovanni), Christina Niessen (Donna Elvira), Ina Schlingensiepen (Donna Anna) and Bernhard Berchtold (Don Ottavio) [Photo: Jacqueline Krause-Burberg]

The whole scenic structure rotated and spun with judicious directorial

thought and attention. Only once did it seem to create unwanted dead space

while we waited for a new positioning. In fact, the set facilitated many

successful groupings and offered opportunities for meaningful dramatic

reinforcement, none more so than the attempted party rape of “Zerlina.”

The deed itself was happening on stage right with the roiling mob stage left,

all the while separated from each other by a jutting piece of wall that came

right to the stage’s edge. This was undoubtedly the most chilling and

suspenseful staging of this moment I have yet encountered.

Later, at the “Don’s” final fateful party, he is portrayed much as

the dissolute, impotent Jack Nicholson at the end of “Carnal Knowledge,”

sitting in his designer leather easy chair, distractedly clicking his remote

and viewing his own Mozartean “Ball Busters on Parade” slide show, with

photo after photo of past conquests flashing on the wall.

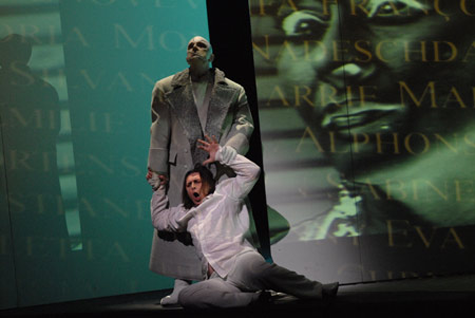

Konstantin Gorny (Don Giovanni), Stefan Stoll (Leporello) and Christina Niessen (Donna Elvira)

Konstantin Gorny (Don Giovanni), Stefan Stoll (Leporello) and Christina Niessen (Donna Elvira)

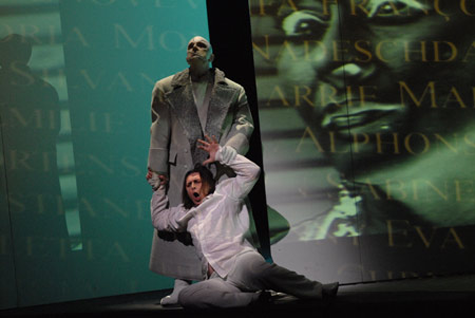

When the “Commendatore” finally nabs his arm in a death grip, hell

arrives in the form of a sex-guilt-induced hallucination of these same images

that now flood the stage, disorienting the audience with strobe-like rhythmic

interweaving that make the “Don” appear to be floating in a visual hell

of his own creation. This was emotion-laden, first-rate stagecraft.

Less effective was the closing sextet. The set did not quite turn in time

for them to be singing full front at its opening, and all were sharing

breakfast at a Victorian dining table, “Masetto” and “Zerlina” with

baby carriage in tow and (judging from “Zerlina’s” Britney Spears bare

bulging belly) another tot on the way. I guess they were all being hosted by

the nun-garbed “Elvira,” now in her convent. It was a bit of a

miscalculated visual, especially after an evening of utmost clarity.

For Robert Tannenbaum knows how to direct singing actors. He knows how to

position them so they can be heard to maximum effect. He knows how to draw

focus to the soloist when there are others on stage. He knows how to

illuminate their relationships and enhance our appreciation of the piece.

This is a director serious about serving the work at hand, and hey, I can

live with an odd, well-intended dining table or two. Tannenbaum scores a

significant achievement with memorably inventive work on this evergreen

standard.

But no amount of fine design or direction could have saved indifferent

music-making, and here, too, Karlsruhe came up with the goods in spades. At

the center of it all, the fine (guest) international baritone Bo Skovhus was

virile, potent, mesmerizing, and troubled; singing all the while with beauty

of tone, dramatic fire, and star power. His effervescent, articulate

“Champagne Aria” was as fine as I have ever heard.

One non-musical note about our star: the production should consider losing

the long straight-haired wig he is made to wear until the final scene, when

he is blessedly “au naturel.” It may be meant to convey a rock star

image, but ends up looking a bit like Ali McGraw on a bad hair day.

Ulrich Schneider (Commendatore) and Konstantin Gorny (Don Giovanni)

Ulrich Schneider (Commendatore) and Konstantin Gorny (Don Giovanni)

Tenor Bernhard Berchtold literally stopped the show with a breath-taking,

superbly controlled sotto voce rendition of “Dall sua pace.” His second

aria was also sung very well, and if a couple of upward leaps sounded a bit

squally, he nevertheless inspired his public to deserved rapturous

ovations.

Guest bass Christophe Fel’s rather stock “Leporello” was well-served

by a big, grainy voice of pleasing timbre, and ample projection. It must be

said that his generally good comic timing lacked in subtlety, and his singing

was marked by several patches of casual acquaintance with the downbeat. And

upbeat. Or any beat.

“Masetto” found a pleasing physical/dramatic embodiment in Mika Kares,

who produced a suave and rolling bass-baritone. His Partner in Peasantry was

the delightful, petite Diana Tomsche as “Zerlina.” Her clear, free lyric

voice wanted a bit more fullness in “La ci darem,” especially since she

otherwise brought a delectable tone and substantial vocal presence to the

stage.

Another guest star, Carmela Remigio offered us a beautiful, pointed,

well-schooled soprano of ample size; always in command of “Anna’s”

heroic music; wedded to a good realization of the role’s dramatic and

directorial demands. While this was a very credible and enjoyable turn, I

hope I may be forgiven if I say that she is not just yet in a league with my

“Anna’s-of-Christmas-Past” including Leontyne Price, Carol Vaness, and

Joan Sutherland. However, time and further experience could certainly bring

her into that company, as she already has a lovely presence and considerable

gifts. (She has recorded the role.)

“Elvira” was a bit of a mixed blessing in Christina Niessen’s

competent hands. Hers is a unique, metallic sound that aptly suited the

shrewish aspects of this role as she unrelentingly pursued her once and (she

wishes!) future prey. I found that although she was always completely in

service of the role and the director’s concept, her technique did not wear

especially well on me, seeming almost strident by opera’s end. Perhaps some

modulating of her heated dramatic zeal would correct some of this

impression.

In his small role, Ulrich Schneider was an imposing, dark- hued

“Commendatore.” The Badisches Staatskapelle played with stylish vitality

and solid commitment under the sure hand of Jochem Hochstenbach.

This “Don Giovanni” strikes a welcome balance between

“traditional” and “what-was-that-about?” and clearly pleased its

public. The raw power of the libido-driven action, coupled with persuasive

musical results made a great case for Mozart’s masterpiece. Not only would

Wolfgang have approved, but he assuredly would also have giddily joined in

this pleasurable evening of “goin’ sexin’.”

James Sohre