Like the nursery rhymes of childhood, Dred

Scott, Harper’s Ferry and John Brown are words that resonate only

indistinctly in the minds of today’s elders; an ahistorical younger

generation knows them not at all. Thus the astonishment that prevailed in the

Lyric’s aged venue at the contemporary relevance — indeed, the urgency

— of the story of the man determined to end slavery in this country —

even by force, if necessary.

Although decades in the making Mechem’s monumental score — it runs

slightly over three hours, less two intermissions — comes to the stage as

racism rumbles beneath the surface of a major political campaign. Brown, if

not totally a’mouldered, would turn nervously in its grave at the sight of

current events.

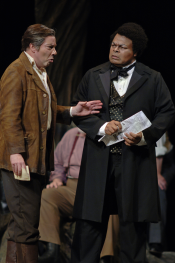

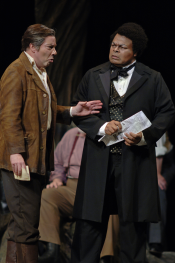

James Maddalena as John Brown and Donnie Ray Albert as Frederick Douglass.

James Maddalena as John Brown and Donnie Ray Albert as Frederick Douglass.

Mechem, author of the Brown libretto as well, has done his

homework in his use of the archives in what is in many ways a documentary

drama. Furthermore, for Mechem Brown is a family matter, for his

historian father once attempted to tailor this story for the opera stage.

Much to his credit, the younger Mechem, born in 1925, has resurrected Brown

in all his ambiguity. At the very center of his opera is the confrontation

between Brown and Frederick Douglass, the eloquent black leader who insisted

upon abolition by legal and peaceful means. Brown, on the other hand, killed

no one, but approved the murder of six men to achieve his goal. Thus

questions of violence and terrorism, ghosts that lingers from the years of

opposition to the Vietnam war, add weight — and darkness — to Mechem’s

tale.

The Lyric could hardly have done better than casting James Maddalena and

veteran black baritone Donnie Ray Albert as Brown and Douglass. Maddalena, on

stage almost without interruption, makes of Brown a towering and commanding

figure, and although Mechem portrays him positively in sometimes mesmerizing

music, he never evades the complex issues encountered in Brown’s position.

Albert makes Douglass, a man to whom ambiguity was alien, a veritable Rock of

Gibraltar in the middle of this story. Indeed, this role must be a major

triumph in Albert’s long and distinguished career.

Death of Oliver at Harper’s Ferry: James Maddalena as John Brown and Patrick Miller as Oliver Brown.

Death of Oliver at Harper’s Ferry: James Maddalena as John Brown and Patrick Miller as Oliver Brown.

Mechem adds a person dimension to Brown’s story with a sub-plot

involving his family and the hesitation of those next to him to support his

plans for the raid on the armory at Harper’s Ferry, the attempt to free

slaves that failed and resulted in his arrest and execution. Son Oliver

Brown, movingly sung by tenor Patrick Miller, and daughter-in-law Martha,

sensitively played by soprano Jennifer Aylmer, underscore the human toll

taken by history.

Mechem’s lush score abounds in moments of richness, such as the love

duet between Oliver and Martha that opens Act Two, when Vanessa Thomas steps

forth from the wings to read a letter by a young slave’s wife and when Oliver dies

in his father’s arms. The score is often marvelous both in sound and

emotion, yet it is always measured. It is tonal and lyric throughout, but

never trite, and a major strength lies in Mechem’s experienced hand as a

choral composer. In many especially moving moments he concludes a crucial

scene with a chorus that never stands by itself, but is always an integral

continuation of what has gone before. The choruses “I’m Free” and

“Stoke the Fire” are as stirring as anything Verdi ever wrote.

Mechem makes no secret of the deep religious convictions that motivate

Brown, who sees himself doing God’s work in fighting slavery. However, he

treats this aspect of his hero’s character with reserve, never allowing him

to seem a zealot — despite many Biblical references and the inclusion of

hymn tunes in his score. There are points in the opera at which Mechem

hauntingly recalls Bach’s passions in his portrayal of Brown’s agony.

Lyric artistic director Ward Holmquist conducted members of the Kansas City

Symphony to fine effect.

It is clear that John Brown, a commission that

celebrates the Lyric’s 50th anniversary, should move on to other stages.

Before it does so, however, revision is needed. The opera now runs over three

hours; and, word from within was that considerable cuts had already been

made.

The first act is totally absorbing in its dramatic force. The final act,

on the other hand, wanders and lacks focus. It could end at a number of

places, and the contribution of the post-scripted Apotheosis to the score is

questionable. One knows by then what Brown’s fate is to be, and to have him

swing visibly above the stage on the hangman’s rope is — well —

overkill and even raises questions of taste.

Donnie Ray Albert as Frederick Douglass with cast

Donnie Ray Albert as Frederick Douglass with cast

The Lyric, set to move into a new performing arts center next year, has

outdone itself in staging John Brown in its current outdated home.

Book — and flag-burning — to mention only two special effects — are

staged credibly. One does not often seek a message in opera, but there is one

here and it is of particular urgency today. “One of the uncomfortable

truths this opera asks us to confront,” writes director Kristine McIntyre

in comments in the program, “is that most people, even when confronted with

a great wrong, are simply afraid to stand up and be counted. We don’t want

to be stirred out of our complacency and we aren’t ready to have our

preconceptions challenged.”

Wes Blomster