15 Jun 2008

See Venice and then die

For the belated Spanish premiere of Britten’s Death in Venice, 35 years after its creation in Aldeburgh, Barcelona seems a felicitous choice.

For the belated Spanish premiere of Britten’s Death in Venice, 35 years after its creation in Aldeburgh, Barcelona seems a felicitous choice.

The 17 scenes in this opera, succeeding at a very tense pace, profited by the Liceu’s sophisticated machinery and lighting equipments to turn the whole into a motion picture, if one unrelated to Luchino Visconti’s award-winning masterpiece Morte a Venezia. Incidentally, the opera and the film share both the same year of first release (1973) and the ominous fame of swan songs of their respective creators, neither of these having survived 1976. At that time, the openly homoerotic charge of Thomas Mann’s original novel (1913) still worked as a stumbling block for mainstream opera-goers, but nowadays the coming-out of respectable old professor von Aschenbach is probably perceived as no big news and definitely not worth such a tragic punishment as death by cholera or, arguably, a “passive” suicide.

Guilt and punishment are such stuff as tragedy is made of. Since the shift in current morals caused feeling of guilt to disappear from the Western public discourse on homosexuality (even less so in Spain, where gay couples are legally allowed to marry), tragicism is no longer an option for staging Death in Venice. Thus director Willy Decker felt bound to pepper the story a bit by adding such hypes as Aschenbach kissing the boy Tadzio on a megascreen or desperately waltzing with him around the stage. True, all that happens as if in a dream, but when the agonizing scholar gets overwhelmed by a heap of naked male bodies choking him to death, one cannot help wondering how counter-heroically all that display of flesh can work, irrespective of the viewer’s sexual leanings. Let’s stop it here, lest both the director and this reviewer be exposed as homophobics in disguise…

The tribute to postmodern commonsense having been paid, Decker felt free to follow the libretto as literally as librettist Myfanwy Piper had done with Mann’s novel. His Venice is a disquieting city peopled by ruffians, gondoliers, porters, whores and peddlers of dubious goods and services, their faces and clothes painted with garish clown-like colors. The hollow cosmopolitan socialites assembling in the Grand Hôtel des Bains at the Lido are their victims, yet Aschenbach cannot sympathize with them either. All he is after is ideal beauty, whether in a Caravaggio painting on display at a museum or in Tadzio’s angelic face. In the end, both images morph in front of his eyes into one nightmarish obsession, while the Gods of Greece — Apollo and Bacchus — fight over his soul with contrasting messages from heaven, as in a mystery play. The sets are gorgeous, with blue skies recalling Magritte and pitch-black waters in realistic movie projections.

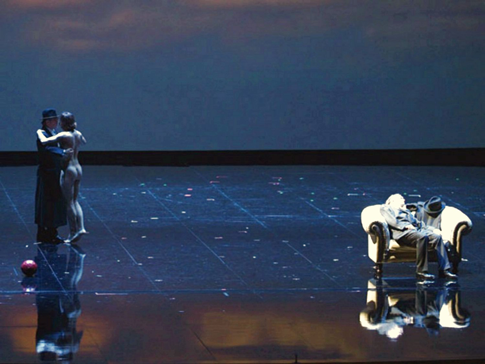

left: Uli Kirsch (Tadzio) [with Aschenbach’s Dopplegänger], right: Hans Schöpflin (Aschenbach)

left: Uli Kirsch (Tadzio) [with Aschenbach’s Dopplegänger], right: Hans Schöpflin (Aschenbach)

The same struggle between life and death breathed from the orchestral pit, mirroring the shifts of wind and tide from the iodine scent of the open sea to the heavy stench of the Lagoon in Summer and back — a common experience for Venice visitors, cleverly described in the libretto. Under Sebastian Weigle’s baton, the taxing score emerged in a glory of harmonies and colors: full-tone scales alternating with polytonalism, piano with Java-style gamelan and far-away echoes of the Baroque. Also the singing company was top-level. The German tenor Hans Schöpflin spun his exquisite mezza voce over the stream of inner monologues and extatic flourishes devised by Britten for his aging mate Peter Pears. Aschenbach’s protean opponent, tempter, flatterer, was the Texan baritone Scott Hendrick, always magnetic throughout his seven so diverse roles. Countertenor Carlos Mena, a reputed Baroque specialist, lent his sunny and mellow alto range to Apollo’s oracles. Within the swarm of cameo roles, particular praise was deserved by the sanguine Begoña Alberdi in the double bill of Strawberry Seller / Newspaper Seller, and by Leigh Melrose, a New Yorker, whose extended narrative solo as The English Clerk in the travel bureau (“In these last years/ The Asiatic cholera has spread/ from the Delta of the Ganges”) conveyed a thrill of Doomsday.

Carlo Vitali

Death in Venice, Act 2, sc. 10 (The strolling players)

Death in Venice, Act 2, sc. 10 (The strolling players)