08 Feb 2009

Poaching in Cologne

One definition of “poach” is “to take or appropriate something unfairly.”

One definition of “poach” is “to take or appropriate something unfairly.”

And that seems to be what Cologne Opera has facilitated at its latest premiere. For it has taken Albert Lortzing’s comic opera Der Wildschütz oder Die Stimme der Natur (The Poacher, or The Voice of Nature) and allowed the creative team to appropriate it as the basis for some wildly divergent production choices (this interpretation is shared with Stuttgart Opera).

Der Wildschütz is seldom performed outside of Germany, which is a pity since the score has some wonderful set pieces and arias, some of which turn up now and again on student recitals, gleaned from operatic aria anthologies. (I myself sang “at” a couple of them in college.) The plot is convoluted to be sure, even by normal mistaken-identity-royalty-in-disguise standards. But given the right production and good musical standards, it is capable of giving much pleasure.

Happily, “good musical standards” Cologne had in ample supply, most especially with its roster of soloists. Miljenko Turk is a house treasure, possessed of a buzzy, focused, well-schooled baritone; an authoritative, virile stage presence; and an innate musicality. Having already enjoyed him immensely in Billy Budd and Der Freischütz, I was just as taken with his secure vocal assumption of Count von Eberbach. Would that he had not been got up as a faux storm trooper for the first scene.

The engaging Hauke Möller always put his pleasing lyric tenor in good service to a physically wiry and agile performance as Baron Kronthal. Although boyishly handsome (at times a ringer for Sean Penn in “Milk”), this ectomorph was not flattered by putting him in knee-length britches and an apron that unfairly highlighted a good-looking guy’s skinny calves and knobby knees. He’s the romantic lead, people! Okay, okay, he did make his first appearance as a swaggering, helmeted, sunglasses-wearing NASCAR driver, someone’s idea of a vision in yellow. (David König is that “someone,” on the blame line for the evening’s variable costumes.)

In the title role of the “poacher” Wilfried Staber’s Baculus sang particularly well, his sizable, clearly pointed bass and animated presence welcome in his every appearance (even as he looked duff in his too-formal suit, red bow tie and horn-rimmed glasses). Tall (no, really tall), lanky, orotund bass Jochen Langner was the eccentric Pankratius, here demoted for some reason from major-domo to a hunchbacked chef. I kept waiting in vain for the “Young Frankenstein” joke (“What hump?”).

On the distaff side, Claudia Rohrbach’s pristine soubrette made her every phrase a delight and she scored big (with Mr. Staber) in the delightful A-B-C-D duet. I was (only) slightly less taken with the Countess von Eberbach, Viola Zimmermann, who arguably has the least developed female principal role. Her meaty mezzo occasionally seemed a little slow to respond in a few of the sprightlier passages, although she contributed well to the ensembles and is a poised actress. In the tiny role of Nannette, Opera Studio member Hanna Larissa Naujoks made her brief appearance entertaining.

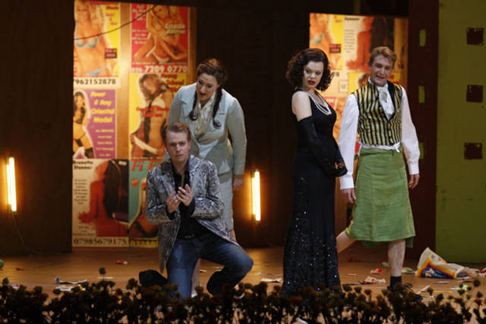

Miljenko Turk (Graf von Eberbach), Katharina Leyhe (Baronin Freimann), Viola Zimmermann (Gräfin), Hauke Möller (Baron Kronthal)

Miljenko Turk (Graf von Eberbach), Katharina Leyhe (Baronin Freimann), Viola Zimmermann (Gräfin), Hauke Möller (Baron Kronthal)

While I have admired Katharina Leyhe at past Cologne outings, her entrance aria as Baroness von Freimann (disguised flatteringly as a male student in one of the evening’s better costumes) was a bit fluttery. She seemed nervous, the low range a mite unsteady, the passage work squishy. She even fumbled and dropped her prop sword as she exited. Once past this, however, her rather light lyric soprano settled into a limpid and often affecting rendition of the part. Still, the role really requires a true diva temperament that seemed just beyond the ken of this gentle performer’s sensibilities.

Other questionable staging decisions aside (and I will chronicle a few), director Nigel Lowery made a fatal core mistake in his treatment of the dialogue. For he chose to present most of it in playback, first in the form of a scratchy “old” black and white film projected on an overhead screen, later as a filtered audio voice-over. All the while, the live actors were stuck on stage, dimly (and dumbly) down lit as they moved around in a Purgatory Pantomime, upstaged by the indifferent media display. This not only consistently frustrated any audience relationship that we tried to develop with the performers, rendering it to fits and starts; but, in a piece that relies heavily on its ability to charm, it rendered “Wildschütz” quite utterly charmless. Maybe I was just tired from the train trip, but after tedious dialogue film number three sputtered to ill-paced life, its way-too-earnest Teutonic close-ups reduced me to uncontrollable giggles at how colossally un-funny it was.) By the time the show reverted momentarily to live recitations in the play-acting scene of ancient tragedies, no amount of melodramatic posing could reclaim it.

Miljenko Turk (Graf von Eberbach), Chor der Oper Köln

Miljenko Turk (Graf von Eberbach), Chor der Oper Köln

Lothar Baumgarten’s lighting design, partly mandated by this Konzept, was unusually erratic. House lights inexplicably stayed at half through the overture. In arias, spots were often everywhere but on the soloists. Area lighting effects were sometimes at the cost of a good basic wash. Curious.

The evening actually started well enough with an amusing show drop that depicted a stylized man and woman, each immersed in reading the same red-covered book, “Wir sind sehr froh” (we are very happy). A gardener laconically watered a profusion of flowers in boxes hung on the lip along the entire stage front. The orchestra struck up a pleasing enough reading under Enrico Dovico. Things bode well. And then, when the requisite poacher’s shot was fired near overture’s end, high hope began to unravel as a gaggle of teenage girls ran on screaming and screaming and screaming as though there had just been a shooting at the Mall.

The curtain flies up to reveal a live couple center stage (Baculus and Gretchen) reading the same books. The playing environment is a big blond wood box with three lobby light-type fixtures overhead downstage (which later explode during the “storm”), and with two, two-dimensional stylized buildings that look to be a depressing factory and/or office building (instead of “a village inn”). Oh, yes, and a large cut-out letter “F” on the floor leans cock-eyed on the wall stage right. While my evil mind raced to many “F’ comment possibilities, it was revealed that it stood for “froh.” Oh. Joy. Well, undeterred, I soon enough wondered what the “froh” was going on.

For the chorus files on in drab working proletariat industrial smocks, all reading the same book (propaganda, get it?) and filing into the factory/office in an endless loop. The militant Count puts a white shopping bag over Gretchen’s head and leads her off stage. Huh? Oh, and then he carries on a life-sized realistic stuffed German shepherd, teeth bared to attack. After threatening the chorus with it, he props it on the prompter’s box, I guess to threaten us. (Laugh, dammit, or I give Rin Tin Tin “the command”.)

Baculus and Gretchen reappear to be hailed as the bride and groom at what is, after all, the celebration of their engagement. But they spend their first duet collecting up all the many overcoats which were shucked by the chorus. In due time, the male chorus re-appears as attack dog trainers in white protective body suits, genitals appropriately covered (by what, cod pieces?), sporting bowler hats and combat boots. Two similarly clad men wear life-like dog heads and crawl around, digging up and strewing lots of flowers, and later presenting the Count a real treasure: a decaying buried carcass. (Rene Magritte or Salvador Dali on acid couldn’t have dreamed this up).

Act II transformed into a stage within a stage, topped with another “F” that looks like the Broadway logo for Footloose. Of course this is not set in the script’s billiard room since the Count and Baron do not challenge each other to a billiard game, no, but rather haul out rifles and fire at police marksmanship targets they have hung on the false proscenium walls. The “stage” created is fairly clever (Owen also did the set design) and the various roll drops are a minor source of visual fun. The practical window in one of them provided an opportunity for a sight gag as our sporty tenor leaped through it effortlessly to disappear like Cherubino on the run. But couldn’t Owen have also designed some stairs instead of using two chairs as the only way for characters to get onto the “stage” from the floor? Seeing the principal women hike up and down the chairs while trying to sing was not pretty.

Fünftausend Taler, the most famous aria, was solidly sung by our title character. As for having it develop into a Las Vegas show number with two leggy chorines, and having the set (rather clunkily) evolve into a garish “entertainment strip” like a pre-Giuliani 42nd Street, well, why not? It worked. But then we were stuck with it. Mr. Turk’s vibrant “Heiterkeit und Frölichkeit,” musically the highpoint of the evening, was hamstrung with a scenario of his alternately schmoozing and abusing two prostitutes. By the time the High School girls (and youth chorus) came back on as wide-eyed tourists in porno land, and the chorus defiantly brandished their red books, we had been totally “froh’d.”

Overall, I actually had the impression the production may have been slightly under-rehearsed. Maestro Dovico led a competent reading that was at times spot-on, and other time rhythmically less sure. Certain allegro passages with soloists were marked by bars of unsteadiness. The chorus (under Irina Benkowski) worked hard enough, having their best moments as Act II’s multiple mythic and divine characters. But, if anything they seemed too refined, too cautious, too unengaged.

Der Wildschütz deserves better. Its riches include enchanting echos of Mozart and Weber, and prefigure Johann Strauss and company, even Gilbert and Sullivan. It would seem a perfect work for a professional summer festival. Glimmerglass? Saint Louis? You listening? Get a production team that believes in it, and it’s seriously up your alley.

As it is, we were here left with a dumping ground of unrelated ideas and schtick recycled in good measure from traditional operetta and Regie-theater alike, being served up as old wine in new (breakaway) bottles. I was reminded of a college tour we made one Christmas to perform at military bases in the Northeast Command.

At one very remote site outside of Thule, Greenland, one of our talented comics presented a perfectly memorized and mimicked “Weather Report” routine made famous by George Carlin. It always landed. This night after we had performed our opening musical set to very enthusiastic applause, he began his monologue with all his usual fire and there was not a peep of response. He kept going gamely. Nothing. Then he got desperate and panicked, rushing it, pushing and the silence was still deafening. How could this be? It always worked. Well, we found out later that the audience consisted solely of Danish contract workers who spoke not a word of English.

And that sort of sums up how I felt about this Wildschütz. It was as though they were using a bizarre artistic comic language we didn’t speak: Froh.

James Sohre