Terfel’s admirers would not have been disappointed. His voice boomed

with authority, impressive for its strength, even when he had to sing

dragging a heavy rope across the stage and wade through the real water at the

front of the platform. Terfel’s vocal power always impresses, and he has

done interesting Dutchmen elsewhere. However, in this production, by

Tim Albery, he was not called upon to develop the character. Not long ago,

Albery presented Boris Gudonov as stolid, mild-mannered bourgeois.

This Dutchman was no more ravaged than Daland. When the women and

Daland’s sailors call out to the doomed souls on the haunted ship, they

face the audience and shine lights into the auditorium. When the Dutchman’s

crew do appear, they’re neatly dressed in uniform, as if they’d never

been to sea. Maybe there’s some deep meaning in this, but it could have

been thought through with more focus.

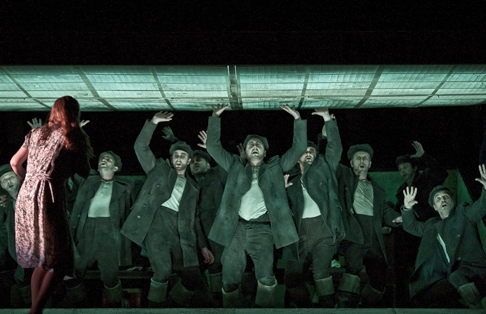

Anja Kampe as Senta

Anja Kampe as Senta

The performance was more interesting, though, for what it brought out in

the music. That glorious overture is a marvel of dramatic scene-painting,

setting the mood for the entire opera. How it’s staged reflects on the

whole production. Here it unfolded against a backdrop of green light and

projected images of rain, with shadowy figures flitting from left to right.

This was interesting, but hardly enough to sustain interest for that period

of time. Nor did it vary, although the score itself is characterized by

distinct developmental phases. This was disappointing because Marc

Albrecht’s conducting shaped these changing themes very clearly, for they

define the duality that is fundamental to the whole opera.

Albrecht’s approach revealed the underlying structure. Wagner wields

leitmotivs like weapons. By juxtaposing the sailor’s cheery love songs with

the savagery of the music associated with the storm and the Dutchman, he

draws contrasts, between stability and chaos. Particularly brilliant are the

crosscurrents in Act Three, throwing the music of the village against the

music of the haunted sailors. This act depicts a “storm on land”, just as

the first depicts a storm at sea. Keeping the different ensembles distinct is

important here, and takes some sophistication. But the Royal Opera House

Chorus excels in intricate ensemble. At last the production sprang to life,

animated by the sheer vitality of the singing.

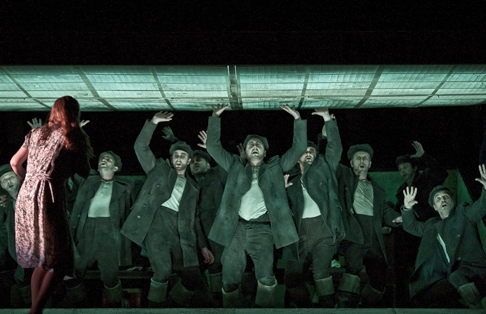

A scene from Der fliegende Holländer with Anja Kampe (Senta) in the foreground

A scene from Der fliegende Holländer with Anja Kampe (Senta) in the foreground

Indeed, the role of the chorus in this opera is sometimes underplayed

since attention usually centres on the Dutchman and on Senta. The influence

of Weber still hung heavily on Wagner. Some of these choruses are reminiscent

of Der Freischütz, another tale of demonic forces. Thus

Albrecht’s vignette-like focus reflects episodic “aria” opera tradition

rather than the overwhelming sweep of late Wagner in full sail. Der

fliegende Holländer is only the first stage of the saga.

Bryn Terfel may have been the big draw, but perhaps this production will

be remembered as the moment Anja Kampe made her name. Anyone who can steal a

scene from Terfel is worth listening to. From Kampe’s small frame emanated

a voice of great power, enhanced by an understanding of Senta’s role. Even

before she meets the Dutchman, she fantasizes about him. The other women work

in a factory, but Senta is by nature a non-conformist, drawn to the wildness

that the Dutchman symbolises. No wonder she knows right away she wants him,

not Erik. Senta is the prototype of Wagner’s later heroines who equate love

with death, and who find fulfilment in redeeming others. This does reflect in

many ways Wagner’s own predicaments, but the archetype becomes wilder and

more cataclysmic. Kampe probably has the ability to make much more of such

heroines in the future, given the productions that make more of the extreme

intensity - madness, even - in these roles. She’s singing Isolde at

Glyndebourne this summer, which will be something to look forward to.

Anne Ozorio