19 Apr 2010

Mark Morris Dance Group: L’Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato

‘Each action will derive new grace

From order, measure, time and place;’ (Milton, Il

Penseroso)

‘Each action will derive new grace

From order, measure, time and place;’ (Milton, Il

Penseroso)

What fitter words to describe Mark Morris’s L’Allegro, Il Penseroso ed Il Moderato which, 22 years since it first amazed audiences at the Théâtre de la Monnaie in Brussels, still has the power to incite wonder, astonishment and joy.

Handel’s pastoral ode is a musical reflection upon Milton’s philosophical meditations on the gregarious, the introspective and the balanced modes of living. His librettist, Charles Jennens, (best known as the librettist of The Messiah), selected and assembled Milton’s poems sequentially, and added the text for Il Moderato; Morris re-arranges once again, moving continually but naturally between contrasting states, the frolicking lightness of L’Allegro tempered by the brooding melancholy and pensiveness of Il Penseroso; and he adds two movements from Handel’s Concerto Grosso Op.6 No.1 to serve as an overture.

Music’s power to express emotional states, or affekts, and to produce ethical responses in the listener, was an essential thesis of the seventeenth-century artistic and spiritual imagination, and one which continued to be upheld by eighteenth-century composers of opera seria. Here, Morris seems almost literally to lift the notes from the page as his dancers physically embody the rhythms, textures and figures of the musical score; his forms present a stunning visualisation of the way music can initiate or allay particular passions and sentiments. And, in so doing, Morris reveals his own, oft-remarked, innate musicality and, more especially, a profound appreciation of the architecture and ethos of baroque musical forms. Rigorous, mathematical choreographic structures are interlaced with ornamented mannerisms and deviant whirls; gestural cliché sits happily alongside surprising idiosyncrasy.

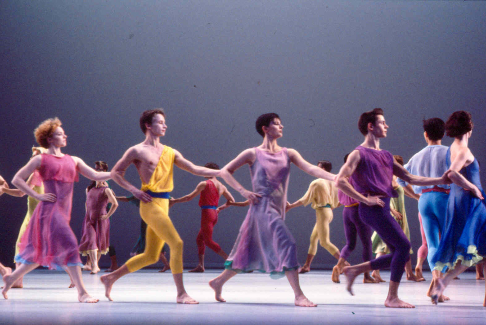

Morris is ably supported by his designers. The warm lighting (James F. Ingalls) effortlessly matches the modulations from light to shade, from clarity to opacity, of Morris’s sequence; it is complemented by Adrianne Lobel’s simple but purposeful conception of the literal and philosophical spaces suggested by text and score - the dancing arena now foreshortened, now extended, almost imperceptibly, by an airy array of descending drops and gauzes. Christine Van Loon’s costumes gladly conjure the pastoral simplicity of classical nymphs and shepherds, the muted pastels of ‘Part the First’ giving way to more vibrant tones in the latter half.

William Blake’s nineteenth-century illustrations of Milton’s poems are cited as a visual influence; but also evoked are the stained-glass windows of a gothic cathedral, panes of many and contrasting colours through which the light reverberates illuminating tales in rich tapestries — such windows as Milton himself described in Il Penseroso, ‘Storied panes richly dight’.

Indeed, the intersection of the vertical and horizontal in Morris’s forms, and in Lobel’s shifting panels and flats, does suggest the meeting-point of heaven and earth, of spirit and flesh, as expressed in the perpendicular architecture of the seventeenth century. Most fittingly then, Morris combines narrative with abstraction for in so doing he combines qualities inherent in seventeenth-century verse, with its integration of the human and heavenly, with those of eighteenth-century music, with its preference for metrical regularity, abstract universality and conceptual clarity.

To focus overly on such weighty matters is, however, to overlook that in this collection of more than 30 dances, gravity is equalled and occasionally challenged by Morris’s trademark wit and irony. In an hilarious hunting scene, three leashed dogs pursue fleeing foxes, pausing momentarily to urinate under a tree; even in such wry fun there is beauty, as the changing landscape is simulated by dancers evoking gnarled branches which form and re-form almost imperceptibly before our eyes. Elsewhere seriousness is alleviated with irreverence, as Morris makes playful reference to the formal salutations and farewells of baroque custom and dance. Throughout there is effortless fluidity between change and stasis, speed and stillness.

The work comprises a rich assortment of solos and ensemble pieces, including a startlingly complicated ‘canon’ for three pairs of dancers — momentarily revealing the technical and choreographic complexity which underpins behind the deceptive simplicity of so much of Morris’s seemingly natural, ‘human’ movement. But ultimately this is a company piece, the group extended to 24 dancers; it is not surprising therefore that it is in the choral scenes where Morris’s invention and confidence is most powerfully evident. Most noteworthy are the final scenes in each Part: in the closing scene, to the celebratory accompaniment of vibrant trumpet fanfares, the 24 dancers form streams of colour, streaking and darting across the stage, conjuring startling pace, energy and joie de vivre — ‘These delights if thou canst give/ Mirth with thee I mean to live’.

The four singers, sopranos Sarah-Jane Brandon and Elizabeth Watts, tenor Mark Padmore and bass Andrew Foster-Williams, all projected the narrative superbly, blending convincingly with the stage drama, enhancing and receding as appropriate. Foster-Williams, in particular, delivered his airs with buoyancy and brightness. Jane Glover skilfully conducted the alert, energised members of the English National Opera Orchestra, bringing freshness and translucence to Handel’s score; the woodwind were especially impressive, exquisitely evoking the pastoral milieu, as when first a lark, and then a whole flock of birds, intricately twist and tumble in fantastic flight, their aspiring arcs symbolised by a scintillating soaring soprano. The New London Chorus were crisp and clear throughout.

The ‘imperfect, labouring’ bodies noted by Joan Acocella in her 1994 critical biography - and which once exemplified Morris’ preference for dancers who whose physicality captured the mortality and genuine ‘flesh-and-blood’ of the human form — were no longer so dominant, replaced by a sweet litheness of form and truly eloquent tenderness. Yet, Morris’s pastoral vision is not an ethereal or idealised landscape but an earthy dominion where the rich diversity of the human spirit is rejoiced. Capturing all the elements which have characterised Morris’s career — beauty and realism, levity and gravity, formal rigour and quirky invention — it remains utterly captivating and uplifting. It is, in the words of Milton himself, ‘linckèd sweetnes long drawn out. (L’Allegro)

Claire Seymour