Sadly, director Rufus Norris, designer Ian MacNeil, and conductor Kirill

Karabits, are desperately out of kilter in this miserable, in all senses of the

word, production of Mozart’s Don Giovanni.

A sparking, spluttering lighting rig occupies centre-stage as the opening

notes of the overture strike up; gradually it rises, resting askew, half-way to

the rafters, and there it dangles redundantly for the rest of the performance,

occasionally emitting a spark or flash. As the Stone Guest’s motif

sounds, there’s some vacuous brutality in the dark recesses, a nameless

women is brought before Giovanni to be abused, and we are clearly being told

that this is going to be a ‘nasty’ evening. Never mind that Da

Ponte’s Giovanni proves to be a rather ineffectual Casanova, not once

carrying out a successful seduction in the course of the opera. We are in a

modern degenerate dystopia, and Mozart and his librettist have clearly been

left far behind in the eighteenth century.

With this re-reading, a crucial aspect of the original is lost: namely, the

class conflicts inherent in the amorous entanglements and betrayals. The

erratic costumes don’t help. Dressed initially in jeans and scruffy

trainers, the Don dons an aquamarine eighteenth-century frock coat for his

opening sexual encounter, complete with antique wig; he then exchanges this

outfit for a slick red suit, aptly devilish over a black thug’s t-shirt,

as debonair man-about-town, gaily throwing parties for the plebs; and finally,

he slips into slobby black pyjamas adorned with the face of Christ and topped

off with a hallowe’en mask. Frankly, Masetto’s shiny blue Primark

suit is more stylish. This confused costuming destabilises our sense of the

power relations between the protagonists; and makes a nonsense of the

Masetto’s avowal, ‘At your service, sir’, when Giovanni

interrupts the wedding party. The Enlightenment’s strict stratification

of society, with its attendant modes of behaviour and codes of honour, has been

jettisoned, making the Don’s philandering seem like tedious

self-indulgence as opposed to radical subversion.

Hyperactive periaktoi, spun wildly in the urban gloom by masked marauders,

present us with fleeting visions of dingy street-corners, Elvira’s

Formica flat, a Seventies’ discotheque, as MacNeil tries in vain to

conjure up an air of reckless abandon and amoral depravity.

All this is a waste of good translation and some strong singing. Jeremy Sams

perhaps indulges in a few too many vulgar double entendres —

‘I’m tired of playing sentry/while he tries to force an

entry’ — but his wit sparkles and the rhyming couplets spill out

easily (perhaps a bit too profusely in the final scene), reminding us of the

fun and alertness of Mozart’s and Da Ponte’s buffa opera.

Sadly, at times it is clear that the director does not care what the cast are

actually singing about: when Zerlina tries to wile her way back into

Masetto’s affection after his beating at the hands of Giovanni’s

thugs (where does it hurt … here, or here …?), providing, one

might think, ample opportunity for some affectionate petting … there is

no chance of an ardent quiver or two, as Norris has seated her on a window

sill, 15 feet away.

Brindley Sherratt as Leporello

Brindley Sherratt as Leporello

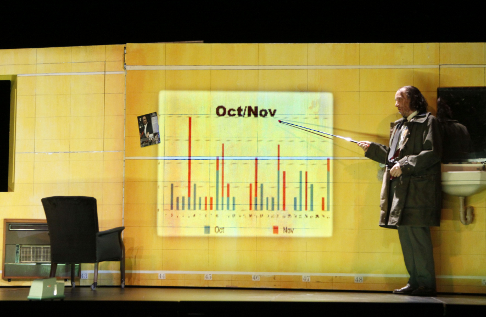

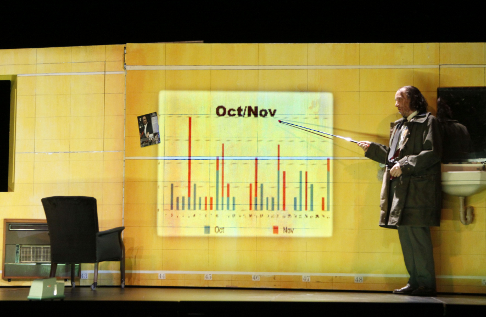

Part of the problem was the pace, or lack of it. Kirill Karabits never once

whipped up the necessary excitement and zip in the pit; the overture was

ponderous and fuzzy, the recitative almost static, and during one of the

greatest of operatic denouements, as Giovanni is sucked down to hell, the only

thing electrifying was the exploding circuit which descended and despatched

Giovanni to his death. Thus, Leporello’s catalogue aria — skilfully

and side-splittingly re-imagined by Sams as a spin-doctor’s statistical

presentation of his master’s conquests month by month, powerpoint,

spreadsheets and all — never generated enough momentum to suggest the

rush of the Don’s romping rampages, despite the artful timing and neat

delivery of Brindley Sherratt’s yobbish Leporello.

The cast tried their best to inject some frisson. The women fared best.

Deputising at the last minute for Rebecca Evans (afflicted with infected

sinuses), Sarah Redgwick was dramatically convincing as the scorned and

scornful Donna Elvira. Attired in a sharp red suit, her ‘Mi tradi’

was clear and penetrating, and she never once became the nagging harridan or

neurotic hysteric of Giovanni’s imaginings. Katherine Broderick has a

sufficiently hefty voice for Donna Anna, but at times it was rather shrill and

ragged, especially in Act 1. Sarah Tynan’s Zerlina was ravishingly sweet,

and she minced delightfully; her bright sound was consistently matched by John

Molloy as Masetto. But whatever happened to subtle innuendo: why, oh why, was

Masetto offered a boxing glove on a silver platter during Zerlina’s

faux-subordinate ‘Batti, batti’?

Sarah Redgewick as Donna Elvira, Iain Paterson as Don Giovanni and Brindley Sherratt as Leporello

Sarah Redgewick as Donna Elvira, Iain Paterson as Don Giovanni and Brindley Sherratt as Leporello

In the title role, Iain Paterson showed that he is a composed, accomplished

singer, able to vary and control his voice, a confident stage presence. Yet,

though the text was clearly enunciated and singing flexible and relaxed, he

didn’t generate sufficient testosterone-fuelled dynamism — maybe

the baggy Jesus t-shirt was to blame. Moreover, it was no fault of

Paterson’s that his ‘Senerade’, delectably sung, made no

dramatic sense: for, after a surfeit of comic crudities, Sams’ inserts

sentimental longings for an ideal love, ‘the one I miss the most’,

yearnings which are totally unconvincing. Mawkish projections of this

‘muse’ — assumingly an idealisation of female beauty —

did not help.

As Don Ottavio, Robert Murray produced a warm tone and presented a generous

heart as Donna Anna’s loyal, steady ‘protector’; he performed

‘Dalla sua pace’ with a consistently smooth line and striking

radiance. Unfortunately, his portrait of integrity and loyalty was not assisted

by the spangly, heart-shaped balloon he was forced to clutch, or the smooching

couples dancing in distance. Murray suffered a fair share of the

director’s indignities, encouraged inexplicably to remove his clothes at

the end of the great Sextet? Matthew Best lacked a monumental majesty in the

opening scene, but was suitable imposing at the close and made a striking

image, slumped, white-suited and pallid against a graffitied wall. The chorus

of identikit demons were, like their surroundings, unfocused and lacking

spark.

The closing scene begins with Giovanni and his side-kick, slouched like

drunken tramps on a grimy street, preparing a pavement picnic of takeaway

left-overs drawn from a discount-store carrier-bag: an image that ironically

rather sums things up — for, like the stale bread rolls they fling

contemptuously at the Commendatore, there really is a lot of garbage in this

production. The mock-fugue finale presents a simple moral: “if

you’re bad you’ll go to hell” — relevant in more ways

than one.

Claire Seymour