These two gentlemen were at it again just now in Zurich, Mr. Vick staging a new Verdi Otello and Mr. Hampson attempting its villain Iago, a late career role debut that did not even require him to change costume from his convincing, indeed moving portrayal of Rick, the professional soldier cum World Trade Center hero.

In Pesaro Graham Vick exploited the explosive hostilities of the Palestinians and Jews in such graphic detail that some audience fled the theater in terror. The Cyprus Greek Turkish tensions do not carry as much emotional baggage or fearsome consequences, at least in the international psyche, but like Mosé in Egitto the contemporary metaphor, here the on-going Cyprus problem, is too striking to ignore. All this is to say that Verdi’s old story, no longer old, was told in contemporary terms.

Unlike the huge ethnopolitical tragedies of Mosé in Egitto, Otello is a personal tragedy that unfolds in war torn Cyprus, though the visible ravages of war could be anywhere. Its opening chorus is not watching the battle but immersed in it by slathering black soot on their faces, stripping off clothes exposing white bodies parts as if wounded.

Fiorenza Cedolins as Desdemona

Fiorenza Cedolins as Desdemona

To preface the opera however, Otello, not in blackface, presented himself alone on the stage thus forcing himself into our close focus for the duration. Maybe it was the lack of the expected blackface that planted the seeds of racism in our minds, and Vick finally allowed overt racism to burst forth only in Act III when a suddenly exposed back-of-a-stage flat said “nigger.” But Vick had made it a black and white opera long before, and on multiple levels. Desdemona appeared in Act I as a phantom bride, a white veiled wife, who moved as if in an Otello dream, his dream of a world of beauty and purity, a sanctuary from the burned black colors of war.

Act IV, the Desdemona act, placed Desdemona in the center of a black stage. She re-entered the wedding dress, covered herself with the bridal veil and became again Otello’s dream as she sang her song and prayer, standing and immobile. We now knew and felt with certainty that this was Verdi’s opera as the Othello tragedy and not the melodrama of a fallen woman.

Acts II and III were in fact the Desdemona acts when she presented herself as an emancipated, worldly woman, possibly unfaithful, even defiant thus taunting the sensibilities of this Venetian general whose Asian sensibilities imagine his woman as veiled, like the burka covered women who praised Desdemona’s exposed beauty in Act II. The opera had suddenly gone globally political and we knew then that its tragically violent outcome was to be understood in universal as well as personal terms.

Judith Schmid as Emelia and Thomas Hampson as Iago

Judith Schmid as Emelia and Thomas Hampson as Iago

Where, you may ask, did Iago fit into all of this? This is where the Zurich casting choices for this remarkable Graham Vick production come into question. Tenor Jose Cura was a gruff, hulking, brutal Otello who held forth magnificently in high Italianate vocal style and whose high style method acting transported his Otello to admirable histrionic heights. Soprano Barbara Frittoli is young and shapely and a formidable Italianate singer whose personal beauty and beauty and range of voice fulfilled the gamut of Desdemona’s expressive needs in this complex concept.

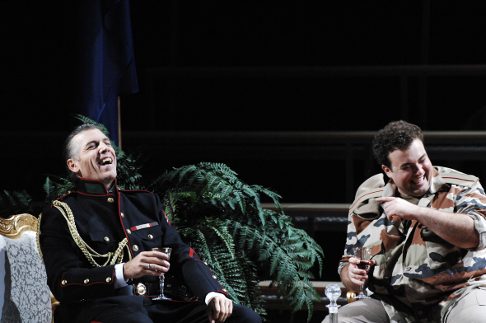

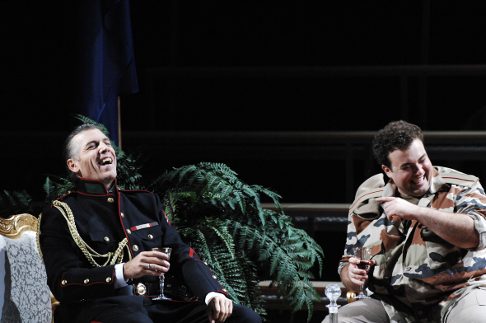

Thomas Hampson simply did not fill the bill as Iago. His size and age precluded a physicality that could color and magnify and therefore interest us in the ugly insinuations Iago dishes out to Otello. In his army fatigues he seemed still the aged Rick Rescorla of the World Trade Center, towering over everyone, and shouting out accusations to Otello like instructions for evacuation. His nemesis Cassio, played by 24-year-old Stefan Pop was equally out of place in age and size, thus depriving this pivotal character of his essential weight and meaning in Verdi’s drama. Vocally however this young singer made the most of Verdi’s musical points.

With the Pesaro Mosé in Egitto and this Zurich Otello Graham Vick has proven himself to be one of our greatest contemporary stage directors, working now in a rich, highly minimal language with the goal of bold and highly pointed storytelling. As well both operas were laden, burdened, over-burdened with contemporary political messages that enriched the inherent political agendas of both operas. With significant participation of his designer, Paul Brown, the visual and theatrical language is refined to few moves, shapes and colors that bring this theater to astonishing heights of a minimalist expressionism.

Thomas Hampson as Iago and Stefan Pop as Cassio

Thomas Hampson as Iago and Stefan Pop as Cassio

Conductor Massimo Zanetti rose to the occasion executing Verdi’s score in biting and cutting detail, pushing its nervousness to an ultimate extreme, sometimes forcing his singers, maybe including Mr. Hampson, to shout rather than sculpt their musical lines (there is however the possibility and suspicion that this was a staging mandate). While this musical brutality may work for the Otello personage it can as well suppress much of the well known subtlety of this Verdi score.

Finally this Otello tragedy was powerfully felt, intellectually and theatrically. It was not musically felt. And that is perhaps the inevitable when a formidable stage director like Graham Vick tackles a formidable work of theater, overlooking that Verdi’s Otello is an opera as well.

Michael Milenski