02 Sep 2014

Glimmerglass: Butterfly Leads the Pack

Every so often an opera fan is treated to a minor miracle, a revelatory performance of a familiar favorite that immediately sweeps all other versions before it.

Every so often an opera fan is treated to a minor miracle, a revelatory performance of a familiar favorite that immediately sweeps all other versions before it.

Such was the case with the wholly persuasive Glimmerglass staging of Madame Butterfly devised by Francesca Zambello. The director has presented this same interpretation at other houses and in this case, familiarity has bred (near-) perfection.

Set designer Michael Yeargan has provided her with a cinematic playground of possibilities. Instead of a picture postcard house with a harbor view, cherry trees and japonaiserie, he has set crucial scenes in the waiting room of the American consulate. Goro shows Pinkerton a scale model of the house, rather than the usual on-site terrain walk. The women’s chorus for Butterfly’s entrance is comprised of American ex-pats gorgeously attired in white Edwardian dresses. Throughout, Anita Yavich‘s costumes were beautifully realized.

To be sure, Cio-Cio-San’s relatives and servants are there as well. And when the Bonze appears behind a scrim in front of an angry ancient sculpture, the consulate wall (upon which is printed the pledge of allegiance) flies out, the cast carries off the furniture and in a split second dissolve we are in a no man’s land of the psyche. As the curse recedes into a diminuendo, simple screen panels descend to suggest an abode. Pinkerton and Cio-Cio-San demurely remove clothing behind separate panels before uniting for a touching wedding night.

Act II finds the heroine back in the Consulate until such time as the cannon goes off in the harbor. Another dissolve reveals three ships in silhouette up left on the raked stage, like ghosts in the mist. In another vivid effect, the stage is completely bare for the Flower Duet and when the piece begins petals cascade down from the flies like a warm shower, blanketing the floor. Then, little Sorrow walks the whole perimeter of the stage strewing fistfuls of blossoms from a basket. Magic. The act ends with Butterfly facing far up stage center, framed by a searing golden light. (It is hard to over-praise the superb contribution of the chiaroscuro lighting by designer Robert Wierzel.)

With the waiting Butterfly immobile up center, Act III begins with a flashback of Pinkerton and Kate courting. Then, in another brilliant touch, a gangplank descends from the downstage right leg, with sailors and Lt. and Mrs. Pinkerton disembarking in Yokohama. A stage-filling configuration of rice paper panels form an overwhelming American flag that fills the stage. These give way to fewer and fewer white panels with finally only one front and center, behind which Cio-Cio-San prepares for her death.

In a final ‘coup de theatre,’ just as the doomed heroine does the deed, the panel flies out, and a deep red curtain falls from the heavens behinds her. Pinkerton shouts his “Butterfly’s” from behind it, then rips it down and rushes to cradle the corpse in a sea of blood red cloth. The goose bumps return even as I write this. I will never see this scene again without comparing it to this moment of unparalleled pathos. I have long been an admirer of Francesca’s fertile creative thinking, and this production found her at her considerable best. After decades of considering the clever Corsaro version at NYCO as the gold standard, this is my new benchmark for innovative illumination of this perennial favorite.

Still, whatever staging innovations may be put forth, the show ultimately rises or falls on the success of the leading soprano, and I can happily report that Yunah Lee was just tremendous. I am not sure what other current exponent of this demanding role is singing this part with such absolute security, freshness, and understanding. Ms. Lee’s well-schooled spinto is a bit (just a bit) on the metallic side, but she knows how to color and couch every phrase to maximum effect. She fully understands the role and gets comfortably under its skin. Every ‘Big Moment’ is thrillingly, memorably delivered. Moreover, Yunah is wholly believable as the 15-year old Geisha even in the proximity of the small Alice Busch theatre. For her overwhelmingly moving, impeccably sung performance, Yunah Lee deservedly earned the most vociferous ovation of the festival as the audience leapt to their feet as one to roar their approval at her curtain call.

Dinyar Vania’s Pinkerton was competent and perfectly acceptable, with his physical appearance suggesting Jerry Seinfeld as a Navy Officer. Mr. Vania effects a somewhat covered sound that delivers better in mid-range than at the top, where it can get just a bit effortful. He sounded best (which is to say very good indeed) at full voice and in ensembles. While Dinyar fully understood the motivations of the cad, he also brought some measure of conflict and remorse to it creating a fleshed out character.

As Sharpless, Aleksey Bogdanov commanded a handsome dark quality wedded to a solid baritone. He brought a slight officiousness and strong presence to the genial consul, not at all the oft-encountered conflicted milquetoast. Mr. Bogdanov’s rich singing and effective stage presence actually made the role memorable. Diminutive Kristen Choi was physically right for Suzuki, and her powerful, pointed mezzo brought astonishing power to her crucial moments.

Ian McEuen had many nice moments as Goro, and shows real promise. Sean Michael Plumb boasted a fine bass as Yamadori, Thomas Richards had the imposing vocal presence and threatening delivery that was needed as Bonze, and Erica Schoelkopf was an assured Kate Pierton. Louis McKinny (Sorrow) threatened to steal every scene whether saluting on cue, playing with his dad’s hat, adjusting his knickers, or even scratching his head. He was beautifully coached, deeply affecting and simply adorable.

Under Joseph Colaneri’s masterful baton, the orchestra played with such style and elasticity, such sensitive to the singers’ every phrase, that they seemed definitive partners in the drama. Even in a slightly reduced orchestration, Maestro Colaneri elicited a reading that was rich with detail and ripe with vibrant colors.

Christian Bowers as Clyde Griffiths

Christian Bowers as Clyde Griffiths

What a treat it was to experience the revised version of An American Tragedy, a complex and rewarding piece composed by Tobias Picker to a libretto by Gene Scheer. Having not seen the premiere production at the Met, but having listened to the duo’s pre-performance lecture, it appears that their fine-tuning of the love triangle and the elimination of material they found extraneous yielded a taut, lean and mean theatrical piece that was absorbing, emotionally engaging, and wholly persuasive.

An American Tragedy was fully realized both as a gripping piece of theatre and as a complicated, jittery, moody, smoldering musical composition. George Manahan conducted an incisive account of the score and the orchestra had its finest hours (of many) lavishing Picker’s score with playing of real distinction. The composer has provided no hiding place from the demands for virtuosic instrumental playing and to a person, the band rose to the occasion. Maestro Manahan ensured that sparks really flew in the many segments calling for orchestral brio, and then he settled things down just as easily to an uneasy peace with glowing legato playing during more inward leaning passages.

The cast is peopled almost exclusively with Young Artists, who are essaying meaty and exacting assignments that would tax performers with ten years more experience. As if they knew they were being mightily tested, they apparently harnessed every ounce of their gifts, and handily passed the test. Would that this piece could indeed be mounted again ten years hence with this same ensemble. They are all uniformly fine, and further experience will only make them better.

The central role of Clyde Griffiths is a huge sing and baritone Christian Bowers was every inch the heart of the piece (if you think Clyde has a heart!). Mr. Bowers over-sang his first pages and his buzzy, well-schooled baritone retaliated for being pushed by sounding (just) a little dry. As Christian relaxed into the part his instrument took on an inviting glow, and he found a good balance of bluster and conversational charm. His attractive presence embodies the social climber with aplomb. Throughout a tireless assault of musical demands, from the extremes of range, to the angularity of the phrases, to the shifting character development, Christian Bowers succeeded on every level. He is surely ready for whatever next big assignment comes his way.

Playing Roberta Alden, Vanessa Isiguen capitalized on the opportunity to be the show’s most sympathetic character and she had us in the palm of her hand. The ache we felt for her was not only because of her function in the plot, but also because she imbued her pristine singing first with love and elation, then later with pathos and desperation. Hers is a radiantly clear high lyric soprano that falls attractively on the ear and is trained to a fare-thee-well. Ms. Isiguen’s total immersion in the character’s plight evoked pity, and raised the stakes of the game.

Cynthia Cook also turned in a very fine impersonation as Sondra Finchley. As the spoiled rich girl with the (eventual) heart of gold, she was physically perfect and vocally secure. Mr. Picker has given the character some of the score’s most extended set pieces, filled with enormously elaborate leaps and melismas. Ms. Cook never faltered, although her generous vibrato sometimes got in the way of her good intentions. Held notes did not always want to behave, and there is some finessing to be accomplished with her technique to tame a tendency to fluttering. Still, Cynthia demonstrated admirable musicianship and considerable intelligence in her traversal of the role.

Daniel T. Curran was spot-on as a spoiled brat of a cousin (Gilbert Griffiths) and his bright tenor was sturdy, pointed and responsive. The matriarch Elizabeth Griffiths was well-taken by Jennifer Root, who contributed a mellow, mature sound that posed a nice a balance. Aleksey Bogdanov lent his well-modulated baritone in good service to Samuel Griffiths. Thomas Richards used every measure of vocal finesse in his arsenal as prosecutor Orville Mason to craft an accusatory cross-examination that built inexorably to a thrilling climax. Meredith Lustig made Bella all she could be and sang with an attractive, limpid tone.

Patricia Schuman came on rather late in the game as the controlling mother Elvira Griffiths and almost stole the show. This seasoned pro showed us how it was done as she strode on and took total command of the stage, acting with searing focus and singing with a ferocious intensity as the Jesus-Mom-from-Hell. Some of the vocal effects she effortlessly deployed were jaw-droppingly successful. Ms. Schuman totally nailed it.

The spare staging was mesmerizing in its simplicity. The basic structure featured a U shaped elevated platform with movable stair components. When a collage of white shirts on hangers flew in as backdrop and legs to suggest the factory, the startlingly apt artistic effect merited applause. Other pieces and two-story wagons were simply and fluidly introduced as needed. The all important boat effect (to enable the theatrical moment of Roberta’s drowning) was marvelous, a bare metal frame of a rowboat on an elevated structure; with a stage width eight foot high “water” cloth in front, lit with undulating waves, and concealing the stagehands operating the effect. The boat containing Clyde and Roberta is on a pivot point that allows it to “capsize,” spilling both up stage. Clyde clambers back on the upended vessel, while Robert drifts far upstage, flailing and drowning as she calls for help in a chilling, well-crafted, piercing musical moment. Erik Teague’s costumes captured the characters and the period.

Peter Kazaras’ sensitive direction was so effective it was barely noticeable. He facilitated well-motivated movement with the actors who were always perfectly placed to sing front. Nothing was done to excess, nothing called attention to the stagecraft, all was characterized by seeming spontaneity. Mr. Kazaras also made good use of the crowds in the church and the factory. And he (and accomplished lighting designer Mark McCullough) masterminded a beautiful opening to the piece, the love triangle personages in individual spots, with Clyde onstage stage center, and his two women towering above on the front platforms right and left. The piece ends with the same stage picture, only this time Clyde is strapped to a chair in the gas chamber. As the music stopped and he sucked in the fumes over and over, and the light finally abruptly snapped out, there was one more gasp. . . from a stunned audience. This was potent writing, well-served by a thoughtful production.

The cast of the Zambello production

The cast of the Zambello production

After Francesca Zambello’s definitive staging of the Puccini, I had hoped for the same experience with the totally different Ariadne in Naxos. The “in” is the key to the approach, since it is not set “on” the island of Naxos in the “opera” portion, nor in a Viennese private theatre for the “prologue” portion. Rather Ms. Z and company have set it in a fictitious town in rural upstate New York.

The concept seemed to spring from the cliché: “My folks have a barn, let’s put on a show,” for the unit set is indeed a barn. Who the wealthy patron is, and why (s)he would engage these artists to perform in this venue is not clear, or perhaps, plausible. Team Z tried very heard to make it work, or at least to distract from the fact that it didn’t. Set designer Troy Hourie provided a workable enough structure with its weathered wood, practical doors and makeshift platform; and he littered this “found space” with bales, farm implements, and all manner of improvised “scenery.” The New York state map painted on the barn’s façade looked intentionally home made and was characterized by red stars that marked the major cities, the most prominent star reserved for Naxos.

Erik Teague’s potpourri of colorful costumes mostly ranged from riotous to the point of garish, with a generous helping of “caricature” mixed in. Fair enough, since the commedia and operatic characters were indeed “standard issue” and needed to be immediately recognizable. Mr. Teague triumphed with his splendid second act gown for Ariadne, a superb achievement that was glittering and alluring and slimming all at one time, calling on an accomplished styling skill that used to transform divas of the immediate past.

Mark McCullough came up with a lighting design that was more functional than atmospheric, although I liked the strands of rudimentary carnival lights hung over the stage that characters could fan out for a drape-like effect. When the Nymphs unhooked and returned them to their original position during their last trio, they seemed like fluffy Norns weaving the fate of the world. Or at least, the barnyard.

As the production began tripping over its concept the most distracting element was arguably the English translation. In an effort to turn it into cheeky vernacular, when Hofmannsthal’s text didn’t suit the gag of the moment, hey, they just changed it! The stuffy Viennese hauteur that informs and drives the piece was nowhere in evidence. To its credit the staging, while busy, was never unfocussed. It just refused to settle down from its manic energy.

In Act Two (the “performance”) the opera was performed in German, with the commedia elements still in English. Such a variation can work as it certainly did in the fresh City Opera staging of the 1970’s which played the prologue in English and the second part in German. But mixing the languages just kept reminding us of the gags of Act I which were now past their sell-by date. By having Ariadne continue to do schtick, to pay attention to the spoilers, and to get engaged by them, neither comedy nor tragedy were heightened by contrast. The principals stubbornly remained Six Characters in Search of a Laugh.

Conductor Kathleen Kelly led a tight, propulsive performance of this Straussian jewel, although the opening instrumental statements were drowned out by the cast entering noisily down the aisles and, once on stage, scuffling their feet and moving set pieces. I was getting ready to turn and shush the people talking in the audience until I realized it was the cast!

I had previously admired soprano Christine Goerke’s work, but I had not heard her since she reinvented herself in her new dramatic Fach. First, she is a game and effortless comedienne. Ms. Goerke now has an imposing, warm tone that is especially rich in the middle voice, but it seemed like almost every phrase was treated as a grand gesture. While she is hailed as one of the current great Elektra’s, Ariadne is a different girl, benefitting from a dash of playfulness and elastic conversational utterances. That Christine has a major talent is not in question. I would only urge her to pull back from forte more often to discover all the nuance and character that are in the role.

I quite liked Catherine Martin’s firm, throbbing mezzo as the “female” Composer. She sang with great passion and a forcefulness that sometimes compromised the spin in those demanding high-pitched arching phrases. The gay romance contrived between this lady musician and Zerbinetta was interesting but ultimately extraneous, and having them remain on stage at the “piano” until the very end subverted the impact of the finale. The creators have given the Composer and Zerbinetta their big moments earlier in the show. The final kiss the coupled shared at the very button of the show pulled the focus entirely from Bacchus and Ariadne who should be having their moment.

Corey Bix managed a Bacchus that was every bit was as well sung as any I have heard. Every tenor must seek his own way to negotiate around the pitfalls of some cruelly difficult writing, and Mr. Bix has found a pleasing way to deliver the big moments with a voice of considerable heft that has a pleasant ring. The slight, almost imperceptible darkening at the top helps him skillfully scale the heights.

Young Artist Carlton Ford has one of the most uncommonly beautiful lyric baritones I have heard in many a year. His Harlekin completely dominated the quartet, the rest of whom were perhaps a season away from making the most of these opportunities, offering more potential and enthusiasm than accomplishment. The tricky section after Zerbinetta’s showpiece really needs seasoned pros to sing the daylights out it for it to be anything other than anti-climactic filler as it was here.

Zerbinetta is one of the Everest’s of the coloratura repertoire to be sure, an exhausting role with repetitive effects that call for no-fail execution Rachele Gilmore is a lovely and fearless performer, and has a beautifully trained instrument that possesses a real sheen. Ms. Gilmore did herself proud, especially since she was not helped by the English translation. Her lengthy aria had a good deal of variety and was enthusiastically received. That said, the endless duplicative roulades and arpeggios and trills and runs and acuti and, and, and, call for a wider variety of execution that is not “quite” yet hers to completely command.

Of the myriad small roles, John Kapusta (Dance Captain) had an appealing voice and an animated presence, and Adam Cioffari’s confident baritone made for a pleasing take on the Composer’s “Agent.” The three nymphs were well matched: Jacqueline Echols’ (Echo) plush soprano was a real treat; Beth Lytwynec served up a commendable account of the low-lying Dryad; and Jeni Houser handled Naiad’s high-flying phrases with skill, although when she pushes the volume the tone can turn acidic.

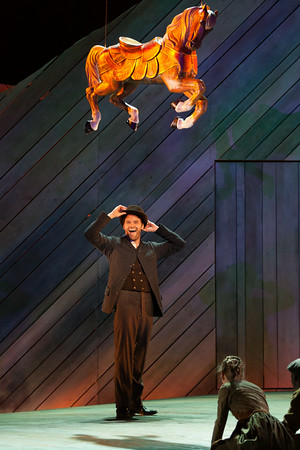

Ryan McKinny as Billy Bigelow

Ryan McKinny as Billy Bigelow

Since the season is over, I don’t have to issue a spoiler alert: Carousel has no carousel. And therein lay the crux of the problem with director Charles Newell’s staging. I can accept that there may be other meaningful ways to suggest the carousel, which is required for the pantomimed exposition that gets the whole show, um, spinning. But Mr. Newell and choreographer Daniel Pelzig did not find the means to serve that moment, to clarify the set-up, to establish the character relationships.

Instead, a pissed off chorus sets out to do some physical gesticulating that looks like River-Dance-Meets-Mark-Morris-Meets-Occupy-Wall-Street. What was all that anger about? Eventually, after principal characters mill around and pretty much go unnoticed, the men assemble in a circle, women jump and ride side saddle on the outside male hip, and the boys tote the girls in a circle like a sack o’ spuds, while the lone suspended carousel horse dips down into the scene, lit with pulsing colors like Disco Donkey.

Perhaps the team thought everyone knew the piece by now, but I had to explain what should have gone on in the opening waltz to my seat partners who had never seen it before and couldn’t figure it out. It is not surprising then that the first real book scene took a long time to jell. With no groundwork lain as to the general relationships of these characters, we stumbled onward as we pieced it together.

Once you forgive the failure of the carousel effect, there was much to admire in john Culbert’s handsome unit set. The layers of three successive walls lined with weathered planks, cut in undulating shapes to suggest waves was quite evocative. The back lighting that was made possible through the gaps in the slats was judiciously used by the multi-tasking Mark McCullough. After the chorus filed in a funeral procession for Billy, the candles they carried in small hurricane lamps got hung on the upstage wall to suggest stars as complemented by the star curtain cyclorama. The platforms and piers afforded for good use of levels and variety of placement.

Best of all, I loved the door in the up center wall/wave. We could tell there was a door there, but as the show progressed it didn’t get used. Act Two began and progressed and it still didn’t get used. And then, in a well-calculated touch, it finally opened to reveal the Starkeeper in a blaze of light. And the show finally came to life. Jessica Jahn mostly eschewed color in her well-realized costume design, and the use of white for the heavenly denizens was effective. Costumes were well-researched and the contrast between haves and have-nots was subtly realized.

What to say about the performance overall? Carousel seemed like a very fine college production staged by an experimenting grad student director. There was precious little chemistry or heat between the actors. It was not until Louise (the excellent Carolina M. Villaraos) and Carnival Boy’s (ditto Andrew Harper) ‘pas de deux’ midway in Two that there was any passion. This dance was a haunting, impressive, straight-forward and traditional piece of staging that more than redeemed Mr. Pelzig for the muddled opening and the rather pat cuteness of such numbers as Blow High, Blow Low. Too bad the finale of the ballet was truncated.

The presentational style kept vacillating all night. Many times, applause was discouraged and ignored at usual opportunities, and at others, it seemed invited. It is hard for the audience to get engaged if the rules keep shifting.

Ryan McKinny brought such a magnetic presence, smoldering sensuality and powerful delivery to last years Dutchman that anticipation was high for his Billy Bigelow. Alas, he couldn’t translate his success into Carousel. Billy calls for a high, bright lyric baritone, and Mr. McKinny is a mellifluous, smoky bass-baritone. Ryan could not decide whether to keep his placement in a natural Broadway ‘talky’ mode, or elevate the focus and make it 'operatic.' The audience was pleased with his Soliloquy even though he kept shifting gears (not always successfully) and semaphored his way through it. I would urge him to just sing the meaning and find one vocal style. He is movie star handsome, for sure and perhaps the movies’ Robert DeNiro has inspired that puzzling accent. Overall, the carefully scripted accents are all over the place.

If Billy comes off as more frat boy than sexy ne’er-do-well, he is ably abetted by frat brother Jigger, aka performer Ben Edquist. Mr. Edquist sings honorably but his fresh-faced villain had no inherent menace and Blow High lacked panache and a sense of debauchery. Andrea Carroll’s Julie Jordan was fairly staunch, not quite melancholy enough although she sang with a winning tone. I appreciate wanting to not represent Julie as the willing victim she is, but Ms. Carroll came off so strongly at times that she would likely have hit him back!

Sharin Apostolou was an enthusiastic and girlish Carrie Pipperidge, and her characterful musical comedy style was the best realized of the evening. If she sometimes came off as too ditzy, she was consistent and appealing. And she did find some determined spunk in Jigger’s attempted seduction scene that made hers the best-rounded character. Joseph Shadday had high notes for days as Mr. Snow but he was too placid. Perhaps he is just too young to have acquired the patina of eccentric charm that usually informs this part.

If, in general, the acting was played to the balcony, Rebecca Finnegan’s harridan of a Mrs. Mullins was at first playing to the outside porch. She settled in to a subtler reading as the show progressed. I quite liked her as the Heavenly Friend although the doubling was visually a bit confusing when she and Billy bounded onstage in white, as if it were a flashback of him cavorting with Mrs. Mullins. Wynn Harmon contributed a notable turn doubled as the Starkeeper and Dr, Seldon. Deborah Nansteel’s stylish Nettie Fowler was an asset.

God bless the hard-working Young Artists that formed the chorus. They sang diligently and were well schooled at moving from grouping to grouping cleanly and with purpose. They executed all that was asked of them within a stylized theatrical representation that was well managed but hollow.

On this occasion, Conductor Doug Peck seemed off form in the pit. Perhaps it was the torrential rain and high humidity that caused the orchestra to start slightly out of tune with a few scrappy woodwind licks. Once the famous waltz tune emerged things hummed along amiably enough. But some of the tempi for charm songs, like the lilting When the Children Are Asleep seemed sluggish, and ignored the possibility to keep the sprightly opportunities moving so that they contrast with the impending drama.

I do appreciate the thought of doing musicals acoustically with full orchestra, but truth to tell they have been the least effective productions of the last four festivals.

Next summer should bring a better fit with Bernstein’s Candide which has often been successfully co-opted by opera companies. Rounding out the 2015 Glimmerglass offerings are a new The Magic Flute, Verdi’s Macbeth (with Eric Owens in his title role debut), and a Vivaldi rarity, Cato in Utica. Ms. Zambello’s pre-show announcement of that title always garnered applause and laughs since the local opera-goers seemed unaware that Cato had ever been in (nearby) Utica.

James Sohre

Casts and production information:

Madame Butterfly

B.F. Pinkerton: Dinyar Vania; Goro Ian McEuen; Suzuki: Kristen Choi; Sharpless: Aleksey Bogdanov; Cio-Cio-San: Yunah Lee; Cousin: Jacqueline Echols; Mother: Aleksandra Romano; Aunt: Vanessa Isigeun; Uncle Yakuside: Christian Bowers; Imperial Comissioner: Chris Carr; Official Registrar: Adam Cioffari; Bonze: Thomas Richards; Prince Yamadori: Sean Michael Plumb; Sorrow: Louis McKinny; Kate Pinkerton: Erica Schoelkopf; Conductor: Joseph Colaneri; Director: Francesca Zambello; Set Design: Michael Yeargan; Costume Design: Anita Yavich; Lighting Design: Robert Wierzel; Hair and Makeup Design: Anne Ford-Coates

An American Tragedy

Gilbert Griffiths: Daniel T. Curran; Clyde Griffiths: Christian Bowers; Elvira Griffiths: Patricia Schuman; Roberta Alden: Vanessa Isiguen; Elizabeth Griffiths: Jennifer Root; Bella Griffiths: Meredith Lustig; Samuel Griffiths: Aleksey Bogdanov; Sondra Finchley: Cynthia Cook; Reverend McMillan: John Kapusta; Orville Mason: Thomas Richards; Conductor: George Manahan; Director: Peter Kazaras; Choreographer: Eric Sean Fogel; Set Design: Alexander Dodge; Costume Design: Anya Klepikov; Lighting Design: Robert Wierzel; Hair and Makeup Design: Anne Ford-Coates

Ariadne in Naxos

Prima Donna/Ariadne: Christine Goerke; Zerbinetta: Rachele Gilmore; Composer: Catherine Martin; Tenor/Bacchus: Corey Bix; Harlequin: Carlton Ford; Master of the Estate: Wynn Harmon; Agent: Adam Cioffari; Dance Captain: John Kapusta; Naiad: Jeni Houser; Echo: Jacqueline Echols; Dryad: Beth Lytwynec; Brighella: Brian Yeakley; Scaramuccio: Andrew Penning; Truffaldino: Gerard Michael D’Emilio; Officer: Cooper Nolan; Wig Maker: Thomas Richards; Farmhand: Matthew Scollin; Conductor: Kathleen Kelly; Director: Francesca Zambello; Choreographer: Eric Sean Fogel; Set Design: Troy Hourie; Costume Design: Erik Teague; Lighting Design: Mark McCullough; Hair and Makeup Design: Anne Ford-Coates

Carousel

Carrie Pipperidge: Sharin Apostolou; Julie Jordan: Andrea Carroll; Billy Bigelow: Ryan McKinny; Nettie Fowler: Deborah Nansteel; Enoch Snow: Joseph Shadday; Jigger Craigin: Ben Edquist; Mrs. Mullins/Heavenly Friend: Rebecca Finnegan; Louise: Carolina M. Villaraos; Carnival Boy: Andrew Harper; Starkeeper/Dr. Seldon: Wynn Harmon; Conductor: Doug Peck; Director: Charles Newell; Choreographer: Daniel Pelzig; Set Design: John Culbert; Costume Design: Jessica Jahn; Lighting Design: Mark McCullough; Hair and Makeup Design: Anne Ford-Coates