12 Sep 2014

Norma in San Francisco

It was a Druid orgy that overtook the War Memorial. Magnificent singing, revelatory conducting, off-the-wall staging (a compliment, sort of).

It was a Druid orgy that overtook the War Memorial. Magnificent singing, revelatory conducting, off-the-wall staging (a compliment, sort of).

Not much more is known about Druid ritual than what Vincenzo Bellini documents in his operatic version of an ancient mistletoe ceremony. He and his librettist Felice Romani then considered what might have happened if this fertility drug had begotten two adorable children and therefore doomed (in this production) an entire civilization to extinction. Their conjecture is complicated by a very human, operatically volatile tangle of fidelity and infidelity.

Make no mistake. Norma is not about human nature. It is about singing about human nature, and if you are the singer it is finding your way out of Romani’s mess by singing long enough, and singing beautifully enough. It got complicated in San Francisco.

Most of all the singing was loud enough, and that is important for a huge theater like La Scala where the opera began (2800 seats) and the War Memorial (3200 seats) where Norma now may be heard as it has never been heard before.

As usual when conductor Nicola Luisotti is in the pit the opera is about the maestro and the pit. The singers are usually lined up across the front of the stage to fall under the direct control of the maestro. He does not hear Norma as bel canto — long, dramatically graceful melodies that soar — but as overwrought emotional outpourings composed to challenge the techniques of big artists. It is big canto, and not only for the singers but also the orchestra who sang out Bellini’s simplistic harmonies as if they were those of Richard Strauss.

Surprisingly Bellini and the audience endured all this (unless as a bel canto purist you were so offended you walked out — though I saw no empty seats after intermission). The orchestra loudly declaimed bel canto subtleties meant to be subtle, and the singers rose magnificently to the challenges of deadly slow tempos or break-neck, ear splitting speed. Just when you thought it was all for nought Norma and Adalgisa, complicit with the maestro, gave a musically splendid duet “Sola, furtiva al tempio,” lines interwoven at a tempo that was at least melodically coherent, if unusually fast.

The second act generally sank under the musical weight imposed by the pit, until the concerted finale “Deh! non volerli [my children] victime.” Here the maestro found enough dramatic resolution occurring on the stage to support the massive energy coming from the pit. And when Pollione, the fickle tenor, declared “O mio dolore” and continued with “contento il rogo [the pyre] io ascenderò” it was spine tingling to the end.

Sondra Radvanovsky may be the epitome of Norma’s in recent history. Not the proto type bel cantista who slides through the intricacies of the role and easily overcomes its roadblocks but the mature priestess, distraught mother, and discarded lover who has a lot of uncomfortable things to sing about. La Radvanovsky has the powerful, luminous spinto voice to color the character, and the range and technique to take on the challenge of accomplishing mature bel canto. Here in San Francisco she accepted the risks perpetrated by the maestro, delivering the “Casta Diva” as melodic stasis, the physical act of vocal production (air moving forward) pitted against frozen motion from the pit (like frozen time in Berlioz’ Les Troyens love duet). Incredibly among the literally thousands of moments when her tone might break during this epic singing event a crack occurred only twice.

Marco Berti as Pollione, Jamie Barton as Adalgisa

Marco Berti as Pollione, Jamie Barton as Adalgisa

Soprano Jamie Barton took on the challenges of Adalgisa. This young artist, already well credentialed in this role, made a coherent dramatic and vocal contrast to the mature presence of Mme. Radvanosky. She brought appropriate virginal voice and presence that validates the casting of a young artist for artistic reasons (in this case like the original 1832 production) rather than for pecuniary reasons. Mlle. Barton displayed a technique well able to cope with Bellini and luckily has already gained sufficient sea legs (stage legs) to cope with this maestro.

Italian tenor Mario Berti sang Pollione. Mr. Berti is not a subtle artist, nonetheless he is a fine artist. Perhaps most importantly he brings true Italianate voice and flair to the War Memorial and the sense that San Francisco Opera may be an international house after all. Without really the range and agility to bring off this role (most glaring in his initial aria

“Meco all'altar di Venere”) he later exhibited some very effective descents into his chest voice plus he succeeded, surprisingly, to sing softly a couple of times. Not to forget the tenorial coglioni that made the final moments of the opera a tenor showpiece (like Calaf in Turandot for example). Following this performance San Francisco Opera announced the Mr. Berti is being replaced by Russell Thomas, a recent graduation of the Met's young artist program, for the five remaining performances.

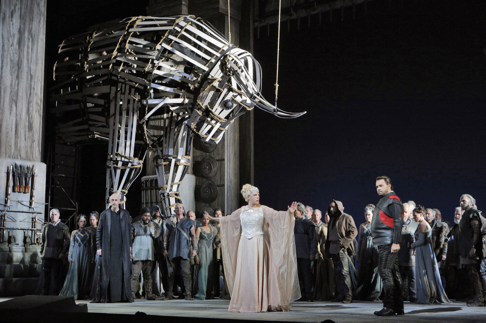

It is a big, new production by American director Kevin Newbury to be shared with Barcelona, Toronto and Chicago. Mr. Newbury has worked operatically primarily in Minneapolis and Houston. But he works also in theater and most recently in film. The production, created with designer David Korins (whose program booklet biography includes restaurant interiors), reflects this range of experience.

The set seemed to be the front of a stage proscenium (a stage within a stage), but also an old fashioned back stage, a mid-western barn, the Old Globe, off-Broadway, a fantasy film and Epic Theater. All these elements crowded at once onto the stage.

The concept seemed to be that maybe the Romans (who wanted the British Isles) snuck a general into Druid country to seduce a high priestess. This dreamed up, far fetched treachery made Messrs. Newbury and Korins think of the Trojan Horse. Since there were already bulls in the Druid mistletoe ceremony the production creators perhaps thought that a Trojan Bull might be constructed (long slats that seemed to be rolled up venetian blinds were carried across the stage from time to time). A huge slatted bull was rolled on stage at the end (explaining those wooden slats) and set afire, Druid soldiers and Norma and Pollione having climbed inside. The barn doors at the back of the stage (wooden) had been barred, trapping the the remaining Druids within the conflagration.

Given the fertility claims of mistletoe one suspects that Messrs. Newbury and Korins tripped out over the word “trojan.” Make no mistake, all this made for an amusing evening.

Michael Milenski

Casts and production information: