30 Dec 2014

Amsterdam: Lohengrin Lite

Stage director Pierre Audi is not one to be strictly representational in his story telling.

Stage director Pierre Audi is not one to be strictly representational in his story telling.

At times in my past encounters, Mr. Audi has summoned forth interpretive results of unearthly beauty and unerring emotional resonance. His successes are among my most memorable opera-going experiences. At other times, Pierre’s over-thinking of subtext has muddied the plot and defused the emotional core of the musico-dramatic source material.

His ambitious Lohengrin for the Netherlands Opera manages moments of haunting beauty, it is true, but random choices of distracting symbols and inexplicable stage movement draw the viewer out of the artistic illusion with alarming regularity.

I quite admired almost all of Jannis Kounellis’ imposing, brooding set design. The cavernous stage of the Muziekthater can be a big space to fill, but Mr. Kounellis has crafted an overwhelming, four story, floor-to-ceiling structure for Act I, that featured seated rows of countless stoic choristers, presiding like unyielding magistrates over a life-or-death trial in a colosseum.

Act II opened up quite a bit, first with an austere balcony for Elsa stage right, then with a more claustrophobic set of receding walls with restricted entrances that nonetheless provided concentrated focal points. For the bridal chamber, Kounellis provided a mysterious set of dark panels that were punctuated with (presumably swan) feathers. Illuminating and apt.

Angelo Figus contributed a wide-ranging, fantastical costume design, with attire often larger than life, bulky, and well, it has to be said, misshapen. The splendid sculpted voluminous capes for the men at the start of Two were replaced by curious white body ‘wraps’ that were unshapely and unflattering. Lohengrin himself appeared not unlike like he was wearing a sculpture of a swan. Best look of the night: Ortrud looked hip and stylish in a red-lined black vamp dress and blond wig. Runner up: the gorgeous visual moment when Elsa was ceremoniously topped with her bridal veil.

All of these visual components were tellingly lit by Jean Kalman. The harsh cross lighting was complemented by well-chosen specials and warm tints at critical dramatic revelations. The separate areas for the conspirators and Elsa in Act II were especially well considered. Mr. Kalman could only do so much however, and his gamely rendered, glowing backlighting effect for the arrival of the swan could not compensate for the fact a train-car full of oars (not a swan) slowly rolled across the stage from left to right as the hero’s voice sounded from off stage left. (See ‘distracting symbols,’ above.)

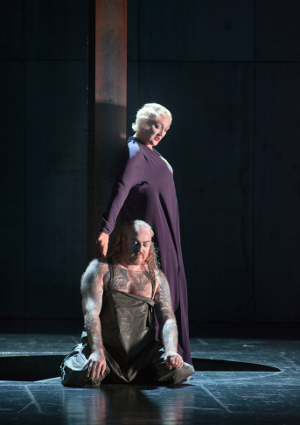

Michaela Schuster as Otrud and Evgeny Nikitin as Friedrich von Telramund

Michaela Schuster as Otrud and Evgeny Nikitin as Friedrich von Telramund

Audi did manage to provide plenty of ideas to chew on. After an opening act that seemed almost Konzertant, replete with semaphoric gestures and ritual choreographic movement, the director infused the rest of the night with more teeming movement that pulsated and morphed with dramatic purpose. The original primitive ritual posturing in which all men had weapons (clubs, staves, knives, pipes), relaxed into more naturalistic interaction to good effect.

The musical achievements were largely impressive. In the first third, the performance was characterized by a rather diffuse sound and lack of forward motion. No import. No inherent burning fire. But as of Act Two, conductor Marc Albrecht seems to have found his muse and from that point on the Netherlands Chamber Orchestra achieved a translucent vibrance and a thrilling sense of ensemble. Ching-Lien Wu’s meticulously prepared chorus went from strength to strength all night long.

The towering vocal performance of the night was the white-hot Ortrud from the laser-toned Michaela Schuster. Ms. Schuster poured out phrase after phrase that etched in the memory as among the finest I have yet heard in this role. The potent Michaela not only sang her socks off, but maybe also sang off the ceiling paint, and she alone was worth the price of admission.

Juliane Banse had most of the assets required as Elsa, including a warm and pulsing soprano that is very sympathetic. But if the occasional smudged phrases and splayed tone are any indication, the part may at this point be a size “just” too large for her inherently lyric soprano. It cannot be denied that her duo scene with Ortrud was arguably the highlight of the evening.

The reliable bass-baritone Günther Groissböck was plagued by an uncharacteristically unfocussed top at the start, but then settled down to regale us with his usual impressive, warm, and powerful vocal presence. Evgeny Nikitin, as an ersatz tattooed biker, was a stolid Freidrich von Telramund. Mr. Nikitin seemed hell bent on pulverizing top notes and ended up barely hanging onto sustained upper phrases with somewhat wooly, straight tone. But, when he sang softer, lo, Evgeny demonstrated a baritone of great beauty and control. More of that, please, sir!

Still, the opera is not named Ortrud, nor Elsa, nor Telramund. The actual title role found Nikolai Schukoff, and his slim tenor, lacking. Mr. Schukoff is handsome and stage-savvy. He has admirable innate musical sensibilities. What he does not have, and cannot suggest, is a heroic voice. Being over-parted, Nikolai resorted to trying to ride the orchestra by manufacturing a pointed, almost pinched delivery, but there was no disguising the fact that there simply was no substantial presence in his smallish instrument. When the opera is called Lohengrin, and that title role calls for a Wagnerian heroic tenor, that shortcoming is a serious limitation.

James Sohre

Cast and production information:

Heinrich der Vogler: Günther Groissböck; Lohengrin: Nikolai Schukoff; Elsa von Brabant: Juliane Banse; Freidrich von Telramund: Evgeny Nikitin; Ortrud: Michaela Schuster; Der Heerrufer des Königs: Bastiaan Everink; Conductor: Marc Albrecht; Director: Pierre Audi; Set Design: Jannis Kounellis; Costume Design: Angelo Figus; Lighting Design: Jean Kalman; Chorus Master: Ching-Lien Wu.