The unresolved tension,

much of it fruitful, some of it perhaps less so, between Brecht and Weill, came

through loud and clear in this estimable performance, given in a new

translation by Jeremy Sams (which was certainly preferable to his

‘versions’ of Mozart, even if not entirely free of the translator’s habit

of drawing attention to himself rather than to the work). Is it an opera? Yes,

of course. As David Drew pointed out long ago, in a 1963 Musical Times

article, one of the most pernicious ideas about Mahagonny has been

‘one that menaces even the most generous-hearted listener — the idea that

Weill intended the work as an attack on the body of the operatic

convention by means of parody or an injected virus (jazz, cabaret etc.). This

idea is wholly false.’ As Drew continued, Weill had far too much knowledge of

and respect for the operatic repertoire, above all Mozart, but others too (not

least, and ominously for his collaboration with Brecht, Wagner), but he was

also genuinely excited by the new paths opened up by composers such as

Janáček and Stravinsky. (He was also a great defender of Wozzeck.)

The problem, for me, is that sometimes, though not always, the musical material

does not present the composer at his strongest; in general, and despite the

songs and tunes we know and love, I find him the more compelling the closer he

comes to his time with Busoni. The Second Symphony and Violin Concerto are

surely his masterpieces. Mahagonny’s music, however, remains on an

entirely different level from Weill’s disappointing music for the United

States. (Whatever his apologists may claim, that is surely, in aesthetic terms

at least, where he ‘sold out’.)

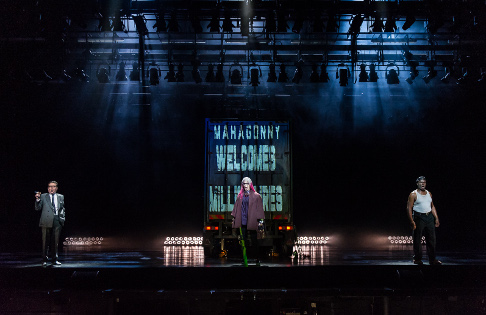

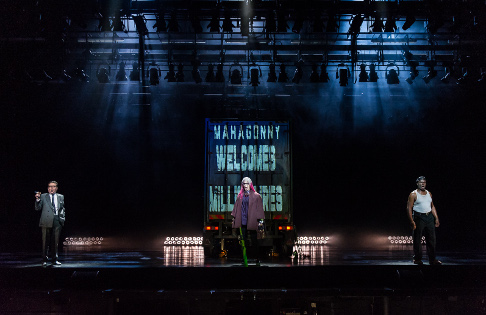

Peter Hoare as Fatty; Anne Sofie von Otter as Leocadia Begbick; Willard W. White as Trinity Moses

Peter Hoare as Fatty; Anne Sofie von Otter as Leocadia Begbick; Willard W. White as Trinity Moses

The greater problem still, though, lies in the collaboration with Brecht,

whose strengths are quite different, and whose adamant refusal to

sentimentalise may sometimes be undone by Weill. (Not that Weill is sentimental

as such, but his æsthetic is undoubtedly different, less didactic,

unquestionably less concerned with alienation, more concerned perhaps with

‘opera’). It is no mean achievement of John Fulljames’s production of

this difficult, perhaps impossible, work, that Brecht’s stature as, after

Beckett, perhaps the greatest of twentieth-century playwrights comes across

with increasing immediacy. There is no attempt to make us ‘sympathise’,

although Weill sometimes does not help in that respect. The conceit, as with

that of the work itself, is admirably simple, though certainly not simplistic.

Mahagonny and Mahagonny grow from a splendidly designed lorry. The

accoutrements of capital, of ‘entertainment’, of neo-liberal barbarism

sprout necessarily: garishly, of course, but retaining focus. Voice-overs and

video projections do excellent work, Brecht’s placards reimagined for our

computer-screen-obsessed age. Perhaps the acting does not always convince as

strongly as it might as acting, but that is part of the trade-off between

Brecht and Weill: an immanent criticism as much as, perhaps more than, a

shortcoming. Choreography is sharp and to the point, for instance during the

‘Mandalay Song’, as the men of Mahagonny — and what an indictment for us

this is of male behaviour, the Widow Begbick notwithstanding! — await their

turn with the prostitutes. I wondered whether the Christ-like imagery at the

end was exaggerated, but to be fair, it is no more so than it is in the work.

Besides, we are at liberty to interpret God’s coming to Mahagonny as we will.

Kurt Streit as Jimmy Macintyre; Jeffrey Lloyd-Roberts as Jack O’Brien; Darren Jeffery as Bank Account Bill; and Neal Davies as Alaska Wolf Joe

Kurt Streit as Jimmy Macintyre; Jeffrey Lloyd-Roberts as Jack O’Brien; Darren Jeffery as Bank Account Bill; and Neal Davies as Alaska Wolf Joe

For, in general, the action is non-specific enough for us to be able to

relate it to when and where seems most appropriate. (It would surely be

bizarre, if in our age of bankster-crime run truly riot, we did not think of

our own characters such as HSBC’s The Revd Prebendary Baron Green of

Hurstpierpoint, surely an invention who would have been too much, too

far-fetched, too agitprop, even for Brecht.) Price variations do their evil

work, and Fulljames, whilst not entirely ignoring the ‘American’ element,

does not overplay it. Weill was certainly alert to the danger of the work

seeming as if it were too much ‘about’ America, writing to his publisher:

‘The use of American names for Mahagonny runs the risk of

establishing a wholly false idea of Americanism, Wildwest, of such like. I am

very glad that, together with Brecht, I have now found a very convenient

solution … and I ask you to include the following notice in the piano score

and libretto,’ although, oddly, it would only appear in the full score, not

in the piano score: ‘“In view of the fact that those amusements of man

which can be had for money are always and everywhere exactly the same, and

because the Amusement-Town of Mahagonny is thus international in the widest

sense, the names of the leading characters can be changed into customary forms

at any given time. The following names are therefore recommended for German

performances: Willy (for Fatty), Johann Ackermann (for Jim), Jakob Schmidt (for

Jack O’Brien) [etc.]”.’ In an English-language version, we necessarily

tilt more towards Americana — the exhibitionist piano-playing of Robert Clark

is an especial joy! — but not too much. Moreover, whilst those of us with

Lotte Lenya in our mind’s ear, may miss her and the rest of the Wilhelm

Bruckner-Rüggeberg crew, we know that this is not a work to be confined to

nostalgic conceptions of Weimar culture.

Mark Wigglesworth is surely one of our most underrated conductors, although

let us hope his forthcoming tenure at ENO will change that; he conducted a

punchy, intelligently varied account. If I found the ‘Alabama Song’ a

little on the slow side, it was slow rather than sentimentalised. Weill’s

Neue Sachlichkeit generally won through, and where more typical

‘operatic’ impulses threatened Brecht’s conception, that suggested its

own humane rewards. Choral singing was well-drilled and not without

‘expressive’ quality: never too much, though. The chorales did their

formal, almost Stravinskian (think not least of The Soldier’s Tale)

work, reacting both with ‘tradition’ and with Brecht. There was certainly a

characterful, properly parodic sense of what Drew, in that Musical Times

article, called ‘the fairground banalities of the trial scene,’

likewise of the horrifying ‘stormtrooper tunes of the boxing scene’. Where,

though, was the Crane Song? Everything is permitted, of course, its omission

certainly so, but it seemed a pity. We should at any rate be grateful that the

once-popular ‘Paris version’, a travesty, with no warrant from Weill, in

which songs from the Songspiel were interspersed with a few

instrumental pieces from the opera, is no longer favoured.

Peter Hoare as Fatty; Willard W. White as Trinity Moses; Anne Sofie von Otter as Leocadia Begbick; Jeffrey Lloyd-Roberts as Jack O’Brien; Christine Rice as Jenny; Kurt Streit as Jimmy Mcintyre; Neal Davies as Alaska Wolf Joe

Peter Hoare as Fatty; Willard W. White as Trinity Moses; Anne Sofie von Otter as Leocadia Begbick; Jeffrey Lloyd-Roberts as Jack O’Brien; Christine Rice as Jenny; Kurt Streit as Jimmy Mcintyre; Neal Davies as Alaska Wolf Joe

The tension between Brecht and Weill was perhaps most clear in the vocal

performances. How to approach these roles as opera singers, in so large a

theatre? For the most part, the cast coped well enough; if their performances

fell somewhat uneasily between (at least) two stools, then perhaps that is

unavoidable in a presentation of the work so conceived. Willard White balanced

gravity and sleaze as Trinity Moses. Kurt Streit as Jimmy had his lyrical

moments — but also, alas, his moments of would-be lyricism. Christine

Rice’s Jenny veered uneasily between home-spun Oklahoma and operatic vibrato,

but her transformations were not so blatant as those of Anne Sofie von

Otter’s Widow Begbick. Stylistically, she was all over the place, but I

assume that in some sense was the point. In any case, the whole, as the cliché

has it, was more than the sum of its parts.

At the time of its first performance, Adorno’s was one of the few critical

voices raised in favour of the work: ‘Apart from the diametrically opposed

operas of the Schoenberg school, I know of no work better or more strongly in

keeping with the idea of the avant-garde than Mahagonny … Despite

and on account of the primitive façade, it must be counted among the most

difficult works of today.’ That difficulty may have lessened, as indeed has

that of Wozzeck or Von heute auf morgen — now when shall we

see that in London? — but it remains, the chill with which Brecht and Weill

react against each other perhaps no less than ever.

Mark Berry

Cast and production information:

Leocadia Begbick: Anne Sofie von Otter; Fatty: Peter Hoare; Trinity

Moses: Sir Willard W. White; Jenny: Christine Rice; Six Girls: Anna Burford,

Lauren Fagan, Anush Hovhannisyan, Stephanie Marshall, Meeta Ravel, Harriet

Williams; Jimmy McIntyre: Kurt Streit; Jack O’Brien: Jeffrey Lloyd-Roberts;

Bank-Account Bill: Darren Jeffery; Alaska Wolf Joe: Neal Davies; Bar Pianist:

Robert Clark; Toby Higgins: Hubert Francis; Voice: Paterson Joseph. Director:

John Fulljames; Set designs: Es Devlin; Costumes: Christina Cunningham;

Lighting: Bruno Poet; Video: Finn Ross; Choreography: Arthur Pita. Royal Opera

Chorus (chorus master: Renato Balsadonna)/Orchestra of the Royal Opera

House/Mark Wigglesworth (conductor). Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London,

Tuesday 10 March 2015.