31 Mar 2015

Fedora in Genoa

It is not an everyday opera. It is an opera that illuminates a larger verismo history.

It is not an everyday opera. It is an opera that illuminates a larger verismo history.

If the operas of Giacomo Puccini are the standard bearers for operatic verismo, the stories of Giovanni Verga hold that place in literature. And there was the Casa Sonzogno [an Italian opera publishing house destroyed by a WWII bomb] that sponsored the famous 1888 competition in which Pietro Mascagni’s Cavalleria Rusticana (libretto on a story by Verga) took first place and became the emblematic moment of verismo.

A now forgotten opera by Umberto Giordano, Mala Vita (An Unhappy Life) took sixth place (out of 73 entries) in that competition. Mala Vita is the grizzly tale of a tuberculosis stricken prostitute and was in fact performed in 1890. Note that Puccini’s La boheme premiered in 1896.

Meanwhile in those same years Giordano saw the famed French tragedienne Sarah Bernhardt as Fédora and Puccini saw la Bernhardt as La Tosca, eponymous plays by Victorien Sardou. This facile playwright gave the public what it wanted — intense moments for dramatic outbursts against a colorful historical backdrop, with no demand that the public wade through motivations or contexts.

The operas Fedora (1898) and Tosca (1900) are very similar pieces. Both are three brief acts, both are about a powerful female in a politically volatile climate, both end in suicide. But where Puccini lyrically expands the personalities of his protagonists into rich, post romantic music, Giordano stays very close to the action making his story an intense, fast moving single action. Lyric moments are brief and fiery, generally less than a couple of minutes, the music looking forward to the more direct, minimalist tendencies of twentieth century music drama.

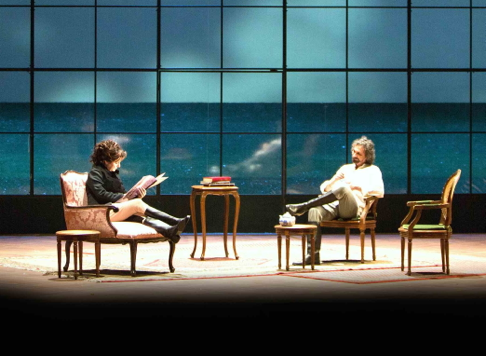

The new production of Fedora in Genoa attempts to bring historical depth to the Sardou play. Stage director Rosetta Cucchi and her set designer Tiziano Santi created a huge, full stage window looking upstage onto an imaginary plain where actions went well beyond the direct, let us say brutal happenings taking place downstage — Fedora’s mortally wounded fiance is brought on stage to die (Act 1), Fedora falls in love with the murderer and betrays him to the police (Act II), Fedora regrets this and kills herself (Act III).

The contexts for these acts played out in this imaginary space were visually splendid if rather confusing. There were battle fields that made us think of the of the 1916 revolution far more than remind us of the the specific context of Sardou’s play — the 1881 assassination of Alexander II. This impression was reinforced by a tableau portrait by costumed supernumeraries of the Czar’s family that made us think of the 1918 murders of the Romanov family. [See lead photo.]

To complicate these contexts the whole opera was played as a flashback — a duplicate Loris (as the by now very aged assassin of Fedora’s fiance) sat on the stage apron for the entire opera (including intermissions) only to walk into the imaginary plain in the final moments of the opera for a brief encounter/recognition of a young goatherd, perhaps the youngest son of the assassinated Ivan the Terrible. Or what?

Daniela Dessi as Fedora, Fabio Armiliato as Loris, Act III

Daniela Dessi as Fedora, Fabio Armiliato as Loris, Act III

Of course none of this really mattered because Giordano’s opera is about the immediate passions of a rich Russian aristocrat, the widow Fedora. Fedora was sung by 56 year-old diva Daniela Dessi. Loris, the assassin of her fiancé and a suspected nihilist, was sung by 59 year-old Fabio Armiliato (both ages determined by birth dates found on the internet). These two formidable artists are partners in real life. Both were in good voice, but voices no longer capable of carving Giordano’s unique vocal exclamations in easy tones, relying instead large, uncolored wooden sounds. It was obvious that both artists knew well and once embodied the vocalism and the musicality of the style, and that they were working hard and honestly to achieve it again. The result was compromised.

Fedora’s friend Olga was enacted by Russian soubrette Daria Kovalenko, ably creating the intended overbearing presence of such a Slavic personality. Pianist (in real life) Siriio Restani, the Carlo Felice house pianist, had his moment in the spotlight giving the Act II solo concert against which Fedora and Loris declare their love in a precious scene that would find itself perfectly at home in the shallow sensualism and sensationalsim of Italian decadentismo, a parallel style to gritty verismo.

Daniela Dessi as Fedora, male supporting cast

Daniela Dessi as Fedora, male supporting cast

The myriad of smaller roles were executed with typical Italian panache.

The greater impact of the evening was lost by a late start for the brief first act, explained somewhat by an announcement about some casting problem, then there was an overly long first intermission. After the brief second act there was a very extended intermission (one can assume there was some backstage drama, left unexplained). The orchestra players became impatient and began stamping their feet, and finally we were given the brief third act. The far less-than-sold-out house gave la Dessi a huge ovation.

The pit at the Teatro Carlo Felice does not offer a great presence to an orchestra. None the less it was obvious that we were in fine musical hands. Young conductor Valerio Galli, already a verismo specialist, made the most of Giordano’s sophisticated score over this too long evening.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Fedora: Daniela Dessì; Loris: Fabio Armiliato; De Siriex: Alfonso Antoniozzi; Olga: Daria Kovalenko; Dimitri: Margherita Rotondi; Desiré: Manuel Pierattelli; Il Barone Rouvel: Alessandro Fantoni; Cirillo: Luigi Roni; Boroff: Claudio Ottino; Gretch: Roberto Maietta; Lorek: Davide Mura; Nicola: Matteo Armanino; Sergio: Pasquale Graziano; Michele: Roberto Conti; Boleslao Lazinski: Sirio Restani. Chorus and Orchestra of Teatro Carlo Felice. Conductor: Valerio Galli; Metteur en scène: Rosetta Cucchi; Set Design: Tiziano Santi; Costumes: Claudia Pernigotti; Lighting: Luciano Novelli. Teatro Carlo Felice, Genoa, March 25, 2015.