Audience members packed into the church hall at the Church of the Covenant on

East 42nd Street to witness the spectacle of a small, emerging

company taking on one of the grandest operas in the

common repertory.

While not a traditional performance space, the production team managed to

make this small church hall feel much like a genuine theater. Creative lighting

placement added to the authenticity of the theatricality, and while the set was

simple and unchanging for the duration of the opera, it was beautifully

designed and offered a basic backdrop for the action of the opera. The

stadium-style set suggested a metaphor oft-utilized in many previous Carmen

productions — that Carmen and Jose are but two sparring members of a

bullfighting ring.

Indeed, the entirety of the production existed in the realm of the

traditional, taking very few liberties that might have contributed to a more

creatively imagined Carmen. At the same time, the production found its

strength in remaining traditional. The costuming was temporally nebulous and at

times inconsistent, but in general costume designer Taylor Mills offered

beautiful displays of craftsmanship, in particular with Micaela’s and

Carmen’s attire. The score was well-preserved, with few cuts. This allowed

for the audience to experience beautiful music often missing from productions

by smaller companies, particularly the chorus numbers, which shimmered in this

production, especially those sung by the female chorus.

The orchestra was on the same level as the audience, but partitioned to

create a semblance of a pit. There are few things more pleasing than the

opportunity to hear a full, unreduced orchestra; however, in this case, the

orchestra provided proof that bigger is not always better. The orchestra, under

the baton of music director Alden Gatt, grew increasingly ragged throughout the

night, with some notable moments of unraveling that were obvious even to the

untrained ear. Intonation and rhythmic problems were rampant throughout the

night, while dynamics and musical variation were sorely underutilized. Gatt

appeared at times oblivious to the breathing needs of his singers, forcing the

singers into some awkward phrasing choices. There were moments of beauty,

however, which hinted at the potential of this orchestra with some polishing,

particularly during the overture and entr’acte.

It is to the credit of the fine group of singers that they managed as well

as they did. The ensemble of singers struggled against a languid orchestra to

stay on the beat, but they pulled it off admirably, especially in the jaunty

smuggler’s ensemble at the close of Act II. The vocal talent was remarkable

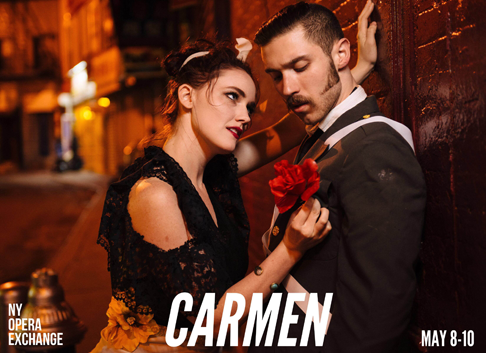

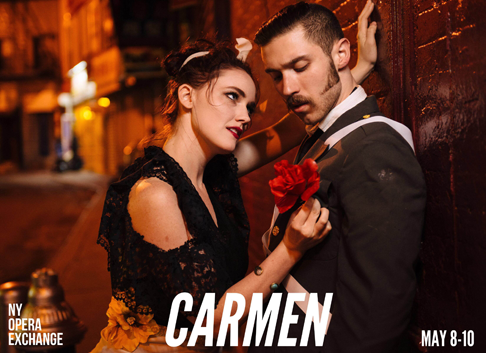

and the strongest element of NYOE’s Carmen. Avery Amereau (Carmen)

has an effortlessly rich mezzo-soprano voice worthy of any professional stage

in the industry, with the charisma to match. Victor Starsky’s Don Jose is

terrifying and compelling, with a voice that performs vocal acrobatics with

strength and beauty that remains undiminished through his final line. The

scenes between Amereau and Starsky were electric like nothing else in the

opera, both vocally and dramatically. The ensemble scenes sagged beneath banal

and stiff staging, but vocally, each singer shone with professionalism and

artistry. Of the smaller roles, Kate Farrar (Mercedes) stunned with a

remarkably rich mezzo-soprano sound, while Kaley Lynn Soderquist (Micaela)

soared through her high range.

Despite the kinks in this production, New York Opera Exchange is onto

something, which is bringing together a community of artists, entrepreneurs,

and culture-seekers. Artistic Director Justin Werner manages to infect others

with his enthusiasm through sheer force of charisma and passion. Only four

years old, New York Opera Exchange has serious potential to grow in excellence

and artistry, and this vibrant production of Carmen suggested the

beginning of this budding future.

Alexis Rodda