The opera, composed in 1985-1988, received its North American stage première in March 2016 at the Park Avenue Armory. Indeed, there were moments of the music that were stereotypically unbeautiful, particularly during the hammered clangor of the first movement. This opera does not make for "easy listening". But these moments, challenging the ear and mind of the listener, are beautiful, at least in the Marxist sense of the word, illustrating the rhythms and realism of human existence as they jolt us out of futile reveries and delusions of myth. This production of De Materie, directed brilliantly by Heiner Goebbels, was surprising in many respects (and, yes, I'll get to the sheep). Yet it was Andriessen's music, performed in all its miraculous starkness by the International Contemporary Ensemble, that elevated the performance to what will surely be remembered as one of the top cultural events of the year.

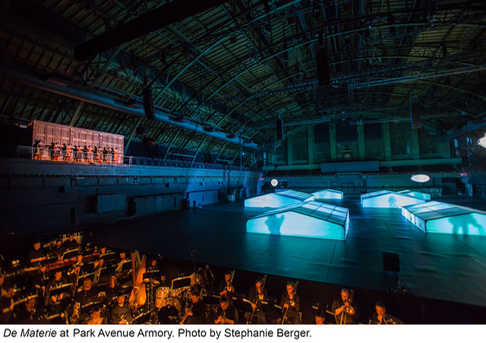

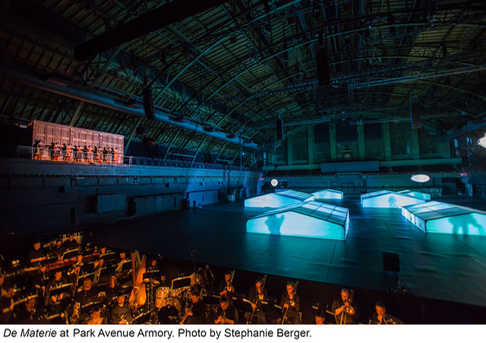

The first movement, intended as an evocation of the Dutch seventeenth-century ship-building industry, opens with the same brutally loud, metallic chord repeated 144 times in the brass and percussion. In De Materie Andriessen turns minimalism on its head in the same vein of his 1975 Workers' Union, which is scored for "any loud-sounding group of instruments"; repetition and process music get melted down into something more earthy and dissonant. The sounds were made even more elemental and unexpected by their sources' location; the musicians were partially obscured from the audience but must have been steered with precision by conductor Peter Rundel. The brash bangs and clangs contrasted bitingly with the human voices interspersed as Chorwerk Ruhr began singing from a balcony. These sounds were juxtaposed with the elegant visuals of Florence von Gerkan's costumes and Klaus Grünberg's stage and lighting design: glowing tents arranged like a checkerboard along the enormous black stage of the Park Avenue Armory; likewise glowing blimps floated languidly overhead. Occasionally the text of the vocals would appear in wavering font along the side of a tent or blimp. However, this wasn't a narrative meant to be followed linearly but rather glimpsed in momentary bursts, through the cacophony and confusion.

Throughout the second, third, and fourth movements, sharply defined musical moods were likewise paired with abstract, sleek visuals and Goebbels' continually startling direction. During the second movement, a stunning 25-minute long aria was sung by soprano Evgeniya Sotnikova in the role of 13th-century mystic poetess Hadewych. As she sang, her face frequently obscured by her dark robe, a procession of rectangular-costumed figures bowed and posed and held their bodies in contorted positions, scattered throughout a checkerboard of pews. Occasionally their positions would change; at one point a burbling bassoon interrupted the legato vocals and strings. The next movement—a scherzo to the second movement's adagio—featured a team of dancers choreographed by Florian Bilbao, including boogie-woogie soloists Gauthier Dedieu and Niklas Taffner. Jazzy, pointillistic music was here paired with a Mondrianesque acrobat show, visually centered around a pendulum and the color blocks (red, yellow, blue, black, white) associated with the early twentieth-century visual art movement De Stijl. The frenzied dancing continued; the musicians' platform rotated across the stage; and finally, 100 Pennsylvanian sheep made their way onto the stage.

The fourth movement was a bit anti-climactic; I had heard about the sheep but couldn't discern their purpose, other than to make the final 25 minutes of the opera somewhat awkward and smelly. Audience members coughed and buried their noses in their sleeves; I don't envy whoever's job it was to clear the stage of sheep excrement in between performances. As the sheep followed each other around the stage, occasionally eliciting a humorous "baa!", the final portrait began. Dancer Catherine Milliken read out Marie Curie's regretful reminiscences, first accompanied by simple, repeated chords from the percussion and then by silence. She continued reading aloud, both from Curie's diaries and from her Nobel Prize acceptance speech, as a group of silent men filed into the performance space, in a visual echo of the sheep. Eventually, the percussion crescendoed on a recurring metallic tone; the opera, quite suddenly, was over. I thought surely I had missed something. What were the sheep there for—as a further commentary on the state of humanity? Another tile in the mosaic of Dutch culture and history? The entire fourth movement felt contrived, not to mention confusing. And yet, it seemed so far from reality as to negatively illustrate reality, bringing about what Goebbels laid out as his goal in the program note: "art, and theater too, should not imitate reality nor represent it, but it should insist on the difference to empirical reality." Andriessen's opera—and Goebbels's production of it—is extraordinary in its illumination of the chasm between art and reality, the instability of matter and of spirit, and the beauty of ugliness.

Rebecca Lentjes