23 Oct 2016

The Nose: Royal Opera House, Covent Garden

“If I lacked ears, it would be bad, but still more bearable; but lacking a nose, a man is devil knows what: not a bird, not a citizen—just take and chuck him out the window!”

“If I lacked ears, it would be bad, but still more bearable; but lacking a nose, a man is devil knows what: not a bird, not a citizen—just take and chuck him out the window!”

Nikolai Gogol’s logic-defying tale of a runaway nose is magnificent in its extravagant absurdity. But, when Collegiate Assessor Kovalov awakens one morning to find his olfactory proboscis has mysteriously gone AWOL and launches a madcap search for his errant sniffer, it is more than his sense of smell that he is desperate to retrieve. His Nose, inflated in size, status and ego, is now a ‘self’ in its own right; indeed, it has stolen Kovalov’s own sense of ‘self’. He appeals for help to a wide range of state institutions - police, medicine and media: he places an advertisement in the newspaper, “I am giving you an announcement … about my own nose: which means almost about me myself …”

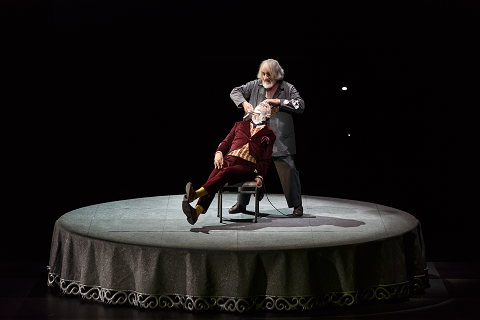

Ambitious, pretentious - a petty poseur - Kovalov has not known his place, and now he has none. This is the ‘dark side’ of ‘The Nose’, but it is not an angle which is illuminated with any great intensity by director Barrie Kosky’s new production of Shostakovich’s modernist operatic romp currently being staged at the Royal Opera House (the first production of the 1928 opera in the House). Kosky does, however, give us a virtuosic vaudeville which makes for an entertaining, if not electrifying, evening. Gogol’s hapless protagonist is a vain, flirtatious bureaucrat whose lust for status among the proto-bourgeois milieu is displayed in his casual amorous dalliances (he uses the military rank of ‘Major’ to impress women) and his obsession with his visual appearance - and its continual display during his daily strolls on Nevsky Boulevard. He awakens one morning to find that his nose has inexplicably vanished. Offended by its ‘owner’s’ habit of allowing the filthy barber Ivan Iakovlevitch to take his nose in his stinking hands when he soaps Kovalov’s cheeks, during his bi-weekly shaves, the Nose makes a bid for independence and embarks on a two-week spree of psychological revenge. Martin Winkler as Kovalov, John Tomlinson as Ivan Iakovlevitch © ROH. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Martin Winkler as Kovalov, John Tomlinson as Ivan Iakovlevitch © ROH. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

The Nose first turns up in a loaf of bread, baked for breakfast by Iakovlevitch’s wife. Discarded in disgust, it then takes on a life of its own. Tormented by the thought of parading along the fashionable Nevsky Prospect sans nose, Kovalov sets off in pursuit, chasing his missing sensory appendage through the streets to the market place and the cathedral; he seeks help from the state and from science but the institutions fail to assist him. And, when the Nose has been tracked down, arrested and returned, the Doctor actually encourages Kovalov to sell the Nose to him in order to make it available for the benefit of modern science and medicine, and his own pocket: “As for the nose, I advise you to put it in a jar of alcohol … then you’ll get decent money for it. I’ll even buy it myself, if you don’t put too high a price on it.”

Shostakovich was in his early twenties when he wrote his first opera, The Nose. He had entered the Leningrad Conservatory in 1919 and graduated in 1925. These were years of multifarious literary and musical manifestos among the cultural avant-garde in Russia and with its deliberately disordered chronology and symbolic distortions of events, it’s easy to see why Gogol’s absurdist satire appealed to the young composer, offering as it does ample opportunity for experimentation with new musical idioms but also allowing for a re-interpretation of the Russian society of the past. At its first fully-staged appearance, the opera was billed as an ‘experimental performance’ by the Artistic Council of Maly Theatre in Leningrad, who feared that some of proletarian audience might be ‘bewildered by the complexity and modernism of the musical medium’. And, Shostakovich does give us a riot of idioms, acrobatic vocalism and kaleidoscopic orchestration, along with a cast of almost 80 individual roles who perform a helter-skelter medley of scenes which race randomly and irrationally through umpteen St Petersburg locales with cinematic slickness. Sung and spoken dialogues alternate with diverse orchestral episodes, the latter serving as satirical embodiments of the dramatic events which ensue as Kovalov runs wildly through the streets in search of his nose, with all its social, and cultural potential. © ROH. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

© ROH. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Shostakovich’s daring musical comedy doesn’t always come off but the bravura bluster of the opera’s theatrical drum-rolls has been ingeniously exploited by Kosky and his set and lighting designer Klaus Grünberg. Wisely, they do not over-complicate things, and instead allow Buki Shiff’s gaudy, exuberant costumes and choreographer Otto Pichler’s vaudeville absurdities to serve as a coloristic complement to Shostakovich’s chaotic, often deliberately cacophonous, score. The garish spectacle is set against a black-grey-white backdrop scheme. Grünberg has placed a proscenium circle within the ROH’s fourth wall, creating a spy-hole through which we can observe, from the safe distance of ‘reality’, the ensuing anarchy. Circular platforms and a few props allow for some suggestion of place but otherwise the ‘city’ is abstract. Gradually any hints of realism are consumed by the escalating nightmare: these small private ‘spaces’ grow in size and become huge circus-rings around which gather a mindless human collective which witnesses the nose-less, near-naked Kovalov’s public disgrace and scandal with rabid relish. The dissident body-part becomes synonymous with personal humiliation.

The cast of The Nose © ROH. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

The cast of The Nose © ROH. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Occasionally, as Kosky gives free rein to the lunacy, there’s a risk of absurdity blunting satire and the whole thing falling off the precipice into farce - some scenes have too much of a Keystone-Cops-capers whiff about them - but Pickler does give us some terrific set pieces. The sacred tranquillity of Kazan Cathedral is shattered when a bevy of belles whip off their fur coats to reveal basques and fishnets and, to a percussion interlude, enact an unbridled physical paean to the giant Nose-God - a sort of black parody of Stravinsky’s Rite. A Tiller-girl line of outsized noses gives us a dazzling tap-dance spectacle which, judging from the guffaws, tickled the audience’s ribs. And, we don’t need Freud to tell us that the nose is a symbol of Kovalov’s fears of lost virility - indeed, Madame Podtotshina mistakes the Nose for a sexual rival of Kovalov - and there’s the requisite phallic imagery to suggest an impotence complex.

But, Kosky takes a couple of wrong turns. Gogol’s protagonist laments, “How can I do without such a conspicuous part of the body? It’s not like some little toe that I can put in a boot and no one will see it’s not there.” And, herein lies a related problem for a director: how to show a missing nose when the singer performing the role clearly has one? Kosky’s solution is to give the entire cast extra-large prosthetic noses - in the director’s words, a nose ‘that morphs an anti-Semitic Nazi cartoon nose with a bit of Barbra Streisand’s nose’ - and to give the nose-denuded Kovalov a circus-clown red conk. But, as the surreal commotion escalates, this only serves to emphasise the farcical at the expense of the potentially subversive. Then, Shostakovich’s Nose is sung by a high tenor but Kosky chooses to separate the Nose from its Voice. The Nose, which grows from animatronic mouse-dimensions to huge tap-dancing colossus, is performed by a boy dancer, Ilan Galkoff - who rightly received a hugely appreciative reception. But, this deprives the opera of one of Gogol’s most powerful scenes, when Kovalov, the preening careerist, is astonished to come across his Nose in the guise of a high-ranking official - a gentleman, as Gogol tells us, in a “gold-embroidered uniform with a big standing collar; he had kidskin trousers on; at his side hung a sword. From his plumed hat it could be concluded that he belonged to the rank of state councillor”. ‘Major’ Kovalov derides the poor, boasts about his fortune and status, and is fixated with image: he misses his nose because its loss inhibits his social climb. So, he summons his courage to confront the Nose with the fact that it is really his nose, but receives - aptly - just a sneer: “You are mistaken, my dear sir. I am by myself. Besides, there can be no close relationship between us. Judging by the buttons on your uniform, you must serve in a different department.” Kosky jettisons this crucial element of the original tale: Kovalov’s dream of personal advancement is destroyed by the personal part that defines his ‘self’ - his Nose has cut itself off to spite its owner’s face. Amid all the wit and hyperactivity, though, there are moments of stillness, and Martin Winkler in the title role is almost single-handedly responsible for the redeeming interjections of bathos amid the bedlam. The moment when having been summarily dismissed by the newspaper officials when he tries to place a classified ad about his missing nose is laden with real anguish, and Winkler - despite - made us pity Kovalov in his shame and anguish, lending this loathsome, lecherous narcissist an almost tragic dimension. This was a tremendously committed, brave performance from Winkler, one that makes the show. Winkler is partnered by John Tomlinson’s shrewd triple-embodiment as the barber Iakovlevitch, the Newspaper Office Clerk and the Doctor. The production opens with a chilling visual image of Iakovlevitch sharpening his knife on his leather belt, and it’s clear that the barber, who is utterly indifferent to his own distasteful odours, is the main suspect implicated in the disappearance of the Nose. As his scolding wife, Praskovya Ossipovna, Rosie Aldridge pounced with fiery anger to demand that her husband remove the offending olfactory adjunct from her house; she negotiated the unalleviated high register - perfect for her foul language and nagging - with aplomb, her voice penetrating but never ear-splitting. Alexander Kravets is an experienced ‘Nose-ist’: he has taken the title role (at the Aix en Provence Festival and Opéra de Lyon) and appeared as the District Police Inspector (at Staatsoper Berlin, Opéra de Lausanne, Dutch National Opera, and the Met). Here, he conjured piercing sounds as the embodiment of the state police, quite literally a bureaucrat shouting - though never nasally! - at the top of his voice. Wolfgang Ablinger-Sperrhacke was splendid as Ivan, Kovalov’s servant, and intoned his balalaika song with melancholy tinged with tongue-in-cheek irony. Ailish Tynan floated the Mourning Woman’s lament in the cathedral with grace and feeling, and Susan Bickley was assured and engaging as the Old Countess. Shostakovich described the orchestra score as an ‘uninterrupted symphonic current’ and conductor Ingo Metzmacher made the individual exclamations and ensemble interjections, which form a backdrop to the various on-stage conversations with the Nose, transparent and biting. We were treated to a deluge of contrapuntal textures and wonderful sounds which at times struck an (intentionally) satirical discord with absurdity on stage The opera is performed in a new English translation by David Pountney. While it has many admirable drolleries, I found the mis-accentuation of the text a bit galling at times. Shostakovich produced his own libretto from Gogol, in collaboration with Yevgeny Zamyatin, Georgy Ionin, and Alexander Preis, expanded the brief original with borrowings from other works by Gogol and a smattering of Dostoevsky. As he changed the narrative to direct speech, Shostakovich insisted that he aimed to achieve ‘a musicalisation of [the] words’ pronunciation’, and that described the vocal parts as building on ‘conversational intonations’. The vivid grotesqueness of Shostakovich’s theatrical satire was undoubtedly influenced by the work of Vsevolod Emilievich Meyerhold. Though the opera ends with an ensemble which reinforces how pointless the story is - it doesn’t benefit the motherland, and has no moral value - Kosky risks reducing the opera to meaningless absurdities. One might take a moment to remember the Book of Matthew and to consider its relevance to Gogol’s tale: “If your right eye offends you (skandalidzei se), pluck it out and cast it from you; for it is more profitable for you that one of your members perish, than for your whole body to be cast into hell.” Claire Seymour Shostakovich: The Nose Platon Kuzmitch Kovalov - Martin Winkler, Ivan Iakovlevitch/Clerk/Doctor - John Tomlinson, Ossipovna/Vendor - Rosie Aldridge, District Inspector - Alexander Kravets, Angry Man in the Cathedral - Alexander Lewis, Ivan - Wolfgang Ablinger-Sperrhacke, Iaryshkin - Peter Bronder, Old Countess - Susan Bickley, Pelageya Podtotshina - Helene Schneiderman, Podtotshina’s daughter - Ailish Tynan, Ensemble (Daniel Auchincloss, Paul Carey Jones, Alasdair Elliott, Alan Ewing, Hubert Francis, Sion Goronwy, Njabulo Madlala, Charbel Mattar, Samuel Sakker, Michael J. Scott, Nicholas Sharratt, David Shipley, Jeremy White, Simon Wilding, Yuriy Yurchuk); Director - Barrie Kosky, Conductor - Ingo Metzmacher, Set and lighting designer - Klaus Grünberg, Costume designer - Buki Shiff, Choreographer - Otto Pichler, Translator - David Pountney, Orchestra and Chorus of the Royal Opera House. Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Thursday 20th October 2016.