For this ‘new’ production at the Royal Opera House, Canadian director Robert Carsen - as he did in Salzburg in 2004 - updates the action from

Hofmannsthal’s mid-eighteenth century, before Enlightenment was superseded by Revolution and Terror, to the time of the opera’s composition, during the

troubled years leading up to World War I.

The curtain rises tantalisingly slowly on designer Paul Steinberg’s Act 1 set, to reveal the formal grandeur of a nineteenth-century Vienna which is

tottering through the increasingly unstable years of the early twentieth. Through the imposing doors of the Marschallin’s chamber emerges Alice Coote’s

Octavian, in crumpled night-shirt; flinging his leg swaggeringly across the arm of a plush Beidermeier sofa in the antechamber, the young Count enjoys a

post-coital cigarette, before Renée Fleming’s Marie Thérèse appears, drawing him back into her den of sexual intimacy.

Renée Fleming (Marschallin). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Renée Fleming (Marschallin). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Peeling back the façade, Carsen and Steinberg present us with the first of three wide-screen vistas. The angled brocaded walls of the bedchamber span the

stage. The focus, naturally, is the bed itself, larger than most studio apartments in present-day London. The polished parquet floors and plush red pelmets

are reminiscent of the rococo luxury of Hofmannsthal’s original locale; the walls are decorated with portraits of men of measure and might - it’s clearly a

man’s world.

Beyond a door to the rear lie a series of connective antechambers and corridors. Later, when the anxious Marschallin requests that Octavian be summoned

back, so that she can remedy her remissness in failing to bestow her departing lover with a kiss, a dozen footmen appear in a flash, anxiously insisting

that they had done their best, but failed, to waylay the Count’s impulsive departure. Silent servants appear throughout the scene, to move a chair, hold a

salver, or re-position a platter. When the curtain falls on this opening Act, one senses the overwhelming responsibility borne by those charged with

sustaining the identity of a city which, at the crossroads of Europe and the centre of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, has been crumbling for years.

Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Act 2 takes us to Herr von Faninal’s nouveau riche mansion. He’s an arms-dealer so it’s fitting that this act is all about regiments: of servants and

seamstresses, of dancing duos, of Ochs’ menacing Prussian retainers. The highly ornamented interior of the Marschallin’s mansion is replaced by a more

modern, monochrome palette. There’s an elegant simplicity about the black and white marble floor tiles, while a mustard-toned Grecian frieze tells historic

tales of war and plunder. Not cultural artefacts but two giant cannons - destined for the battlefields of Flanders? - are the centre-piece of Faninal’s

modish interior. When Sophie and Octavian seek respite from the maelstrom of Ochs’ marauding servants, their hiding place - they nestle between the two

grey guns - ominously belies the romance. And, sure enough, Ochs’ nasties return: the choreography (Philippe Giraudeau) of their vicious humiliation of

Sophie is superb.

Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

As in Salzburg, Carsen replaces Act 3’s usual rustic inn with a gaudy brothel managed by a male ‘madam’. We begin, like the opening, with a façade; for all

the gilt paint and flock wallpaper, the series of doors through which scantily clad women beckon and beguile, recalls the soulless sex-selling of ENO’s

recent Don Giovanni. This is a world of decadent debauchery; at one

wonderfully wry moment, a near-naked man wanders casually and indifferently through the dissipation as Ochs cries in disbelief, ‘Was war denn das?’ (‘What

was that?’). And, Ochs’ temptress, ‘Mariandel’, is no shrinking violet - sporting a blue satin dressing gown atop a cerise corset, she dreams up

indecencies for Ochs that are played out in the neon windows - straight from Amsterdam’s red light district - whose vices push aside the classical

paintings of naked majas, nymphs and Venuses.

Alice Coote (Octavian/Mariandel) and Matthew Rose (Baron Ochs). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Alice Coote (Octavian/Mariandel) and Matthew Rose (Baron Ochs). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

It’s an odd place for the Marschallin to find herself; and the second half of the Act doesn’t quite convince. She should be above such crudeness and

coarseness; and, she knows it. The Murphy bed - confidently flipped down by Mariandel - is again the site of most of the action, as Sophie and Octavian,

bathed in a red glow, canoodle fervently, as the Marschallin graciously, with quiet resignation, accepts that the two youngsters are in love.

Renée Fleming (Marschallin). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Renée Fleming (Marschallin). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

This production was unofficially promoted as Fleming’s London swansong, and there was an autumnal air which straddled real life and theatre. Aided by

Brigitte Reiffenstuel’s gorgeous costumes, Fleming had undeniable stage presence. But, while her bitter-sweet reflections about transience and the

relentlessness of Time avoided a cloying sentimentality, Fleming did not really communicate the Marschallin’s inner life. Her musings needed to be

projected more strongly. She can still glide through a phrase with lovely sweetness and style, and the bloom and lustre are not lost, but they can’t be

sustained. And, Fleming knows this: she saved herself for the big moments, and at times her soprano seemed too reticent to hold Strauss’s ardency. The last

20 minutes of Act 1 saw her tone and timbre recede - the Marschallin’s psychological fragility seemed vocally laid bare. Yet, Fleming showed that she could

still yield the magic: when she gave the silver rose presentation box to her young page for him to take to Octavian, she spun a line of wonderful silky

sheen, a delicious musical anticipation of the formal courtship ritual to come. Conductor Andris Nelsons seemed to quell the orchestral boisterousness and

pace in sensitivity to Fleming (in contrast, in the ensembles he was less judicious and the voices sometimes struggled to compete) and this further lowered

the temperature at times, though during this Act 1 finale Nelsons encouraged some exquisite playing from the woodwind, adding to the sense of

introspection.

Sophie Bevan (Sophie von Faninal) and Alice Coote (Octavian). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Sophie Bevan (Sophie von Faninal) and Alice Coote (Octavian). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Alice Coote sang the marathon role of Octavian with enormous commitment - some may have found her young Count a touch too uninhibited - and acted well.

Occasionally petulant and over-sensitive to slights to his amour propre, this Octavian was more than a match for Matthew Rose’s menacing Ochs.

Even when upset by Marschallin’s honest prophesying, Octavian summoned his stature, and with a sharp, click of the heels made an authoritative exit, not a

young man to let the public face of masculine command slip. There was a discrepancy, however, between the heaviness and occasional lack of focus of Coote’s

lower register and the rich brightness of her top, and vocally her performance did not feel entirely controlled, but she blended beautifully in the

ensembles and overall this was a persuasive performance.

Sophie Bevan sang her namesake’s soaring phrases with ease, and considerable strength; this Sophie was by turns furiously feisty and - particularly in the

final duet - charmingly innocent. But, Bevan could not offer the slithers of silvery caress that we have come to expect. I longed for ‘Wie himmlische,

nicht irdische’ to linger, just a fraction longer. But, perhaps this was not Bevan’s fault; for though Nelsons often took things fairly steadily, the

presentation of the rose felt far too precipitous. Dressed not head-to-toe in silver, but in military black and white, Octavian fairly charged through the

ranks of ceremonial onlookers. Behind the enchanted young lovers, pairs of dancers swirled in stylised fashion during the duet which should seem to hold

Time still and refute the evidence of the opera, and of life, that the clock’s cannot be stopped. The purple light which bathed the scene was not enough to

transport and translate, and was quickly superseded by the white glare of reality during the ensuing tête-à-tête, and later by the lurid green

gleam which accompanied Ochs’ pompous arrival.

Sophie Bevan (Sophie von Faninal). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Sophie Bevan (Sophie von Faninal). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Matthew Rose’s Baron was a revelation. I have never heard Rose sing with such elegance and beauty of tone. Writing in 1942, Strauss recalled the first

performances of Der Rosenkavalier and offered some hints to performers, noting that Ochs was not, as ‘most basses have presented him’, ‘a disgusting vulgar

monster with a repellent mask and proletarian manners’, but rather ‘a rustic beau of thirty-five, who is after all a member of the gentry […] He is at

heart a cad, but outwardly still so presentable that Faninal does not refuse him at first sight.’ Carsen and Rose seem to have heeded the composer’s

advice. Dressed in the stiff military uniform of a Prussian office, this Ochs was no lumbering bucolic buffoon but a threatening lecher, accompanied by a

rifle-toting platoon. Angry at Sophie’s rejection and obvious distaste, Ochs threw her dismissively to the floor. The resonance and charm of Rose’s voice

was an unnerving but rewarding counterfoil to Ochs’ confident menace.

Carsen offers many inventive gestures, quirky details that tickle the imagination but never go too far, and in the secondary roles the cast are

characterful. As the Italian Singer, a matinée idol in white suit and hat, Giorgio Berrugi blasted his way through his aria with a little too much bombast,

but did a good impression of Caruso, effusively handing out his latest gramophone recording. The conspiratorial manoeuvring of Annina (Helene Schneiderman)

and Valzacchi (Wolfgang Ablinger-Sperrhacke) is well-choreographed, as is Alasdair Elliot’s spirited abandon as the cross-dressing brothel owner. Jochen

Schmeckenbecher bullied and badgered blusteringly as Faninal, while Scott Connor’s Police Commissioner was a smooth-operator, coolly departing with the

Marschallin at the close - her next inamorato, perhaps.

Helene Schneiderman (Annina) and Wolfgang Ablinger-Sperrhacke (Valzacchi). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Helene Schneiderman (Annina) and Wolfgang Ablinger-Sperrhacke (Valzacchi). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

In the pit the Orchestra of the Royal Opera House were fervent but occasionally a little ragged under Nelsons’ baton. Certainly he fired the players up in

the graphically pictorial prelude - indeed, the horns let rip with a little too much vigour at the expense of control, and more punch than blend at times.

But, there was too often a lack of finesse.

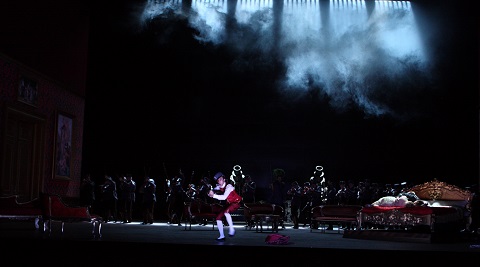

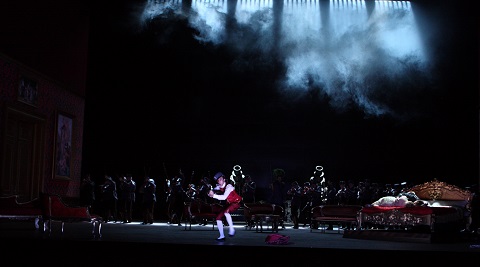

Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Conventionally, the opera’s whimsical coda consists of a playful dash by the page Mohammed back into the bedroom to search for Sophie’s lost handkerchief.

Instead, Carsen slides back the slanting walls of the garish bawdy house and opens up the expanse of the ROH stage, to reveal a row of ghostly soldiers,

headed by the Feldmarschall and with a green-turbaned Prophet in their midst. Faninal’s cannons, shrouded in mist, point towards the slaughter-grounds of

WW1. The grey platoons fall, in slow motion. The outsized Silver Rose may have sparkled like Swarovski crystal but its dazzle was clearly deceptive. The

frisky pastimes of the bordello are over; it seems that future field manoeuvres offer Octavian only an early grave.

Claire Seymour

Richard Strauss: Der Rosenkavalier

Marschallin - Renée Fleming, Octavian - Alice Coote, Sophie von Faninal - Sophie Bevan, Baron Ochs - Matthew Rose, Faninal - Jochen Schmeckenbecher,

Valzacchi - Wolfgang Ablinger-Sperrhacke, Annina - Helene Schneiderman, Italian Singer - Giorgio Berrugi, Marschallin’s Major Domo - Samuel Sakker,

Faninal’s Major Domo - Thomas Atkins, Marianne/Noble Widow - Miranda Keys, Innkeeper - Alasdair Elliott, Police Inspector - Scott Conner, Notary - Jeremy

White, Milliner - Kiera Lyness, Animal Seller - Luke Price, Doctor - Andrew H. Sinclair, Boots - Jonathan Fisher, Noble Orphans -Katy Batho, Deborah

Peake-Jones, Andrea Hazell, Lackey/Waiters - Andrew H. Sinclair, Lee Hickenbottom, Dominic Barrand, Bryan Secombe, Mohammed - James Wintergrove, Leopold -

Atli Gunnarsson; Director - Robert Carsen, Conductor - Andris Nelsons, Set designer - Paul Steinberg, Costume designer - Brigitte Reiffenstuel, Lighting

designers - Robert Carsen and Peter van Praet, Choreographer - Philippe Giraudeau, Orchestra and Chorus of the Royal Opera House (Concert Master - Sergey

Levitin)

Saturday 17th December 2016; Royal Opera House.