Yet one senses throughout Beethoven’s inexperience with the operatic

genre. He toiled on Fidelio for over a decade, through three

versions and four overtures, complaining that it would have been easier to

start over. The result bears the marks of a struggle, not entirely successful,

to impose coherence on conflicting plot elements and musical styles.

The bourgeois domesticity with which the opera begins—based on a

trivial matter of unrequited petit-bourgeois love—alternates, often

abruptly, with the universal struggle for political justice against tyranny.

Beethoven increasingly came to see the latter as the opera’s real theme;

it is no coincidence that the real-world story that inspired the libretto took

place during the Reign of Terror in 1794. Yet he never entirely erased the

traces of the previous, more prosaic theme.

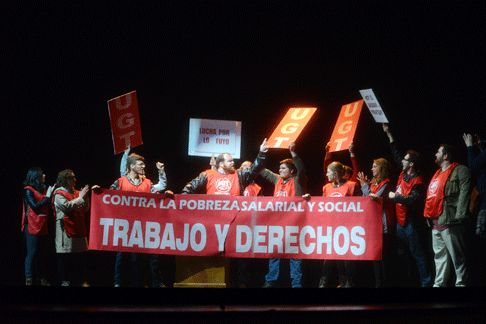

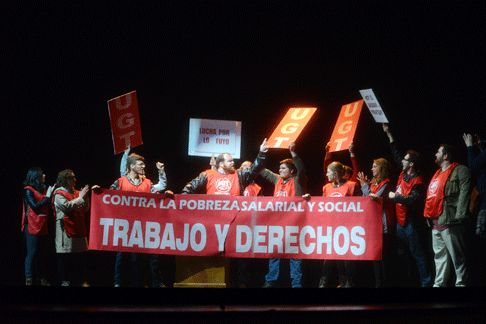

Opening staging

Opening staging

Of course the personal and the political are connected: in order to fight

for universal human rights, Beethoven seems to be saying, we must transcend

more immediate concerns about material comfort, family attachments and personal

safety. Or, more subtly, we must learn that a genuine commitment to the welfare

of those in our immediate surroundings may well imply that we struggle for

universal justice.

Yet Beethoven never entirely succeeds in weaving the personal and the

political into a coherent musical tapestry. Fidelio set a

new standard for music of heroic grandeur: at its best, it nobly portrays

secular idealism by drawing on elements of religious music, as in numerous

choruses and the solo numbers of Leonore and Florestan—and, later, in the

Ninth Symphony. Yet the opera also contains numerous Singspiel, opera

buffa and spoken elements that seem to have parachuted in from

another opera. Struggling to combine the two types of expression,

Beethoven’s score repeatedly thrusts powerfully forward and upwards only

to be brought back down earth by comic relief, lighter music, and spoken

dialogue.

These awkward tensions have an important implication: a great live

performance of Fidelio demands that performers infuse every

moment with vocal and orchestral conviction so powerful as to sweep away all

hesitations and misgivings. In the mid-20th century, many

treated Fidelio as a grand symphony and looked to great

conductors to supply this forward impetus.

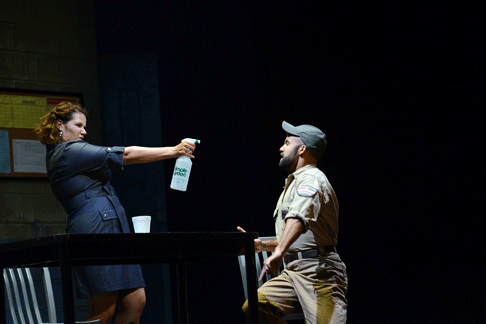

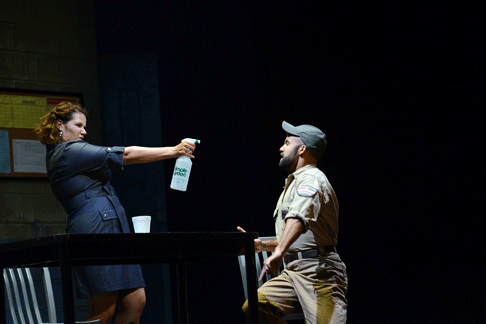

Danielle Talamantes (Marzelline) & Michael Kuhn (Jaquino)

Danielle Talamantes (Marzelline) & Michael Kuhn (Jaquino)

In this spirit, conductor Richard Tang Yuk, director of the Princeton

Festival, invoked the admirable tradition of inserting the

epic Leonore Overture No. 3 before the final scene—a

practice now threatened by musical literalism, short audience attention spans,

and union wage scales. Here, as elsewhere, the slimmed-down orchestra played

smoothly and surprisingly error-free throughout. This is no small feat, as the

score contains cruelly exposed wind parts that occasionally embarrass even the

world’s greatest musicians.

Yet interpretively, the orchestral playing was less than the sum of its

parts. Yuk’s approach to the score—as has been true before in

Princeton—tends to privilege smoothness and accuracy over energy and

attack. He selected cautious tempos and smoothed Beethoven’s dynamics to

the middle of the spectrum. The overtures and the opening to Act 2 were

lovely in places but lacked sweep and drama. A more impetuously inflected

approach to the orchestral score, as Beethoven himself reportedly conducted it,

would have been welcome—even at the cost of a few more bloopers. The

orchestra was also generally too loud when accompanying singers and too soft

(or improperly accented) in grand orchestral moments like the Leonore

No. 3. The dynamics in the vocal score—except in a few

exceptional numbers—tend to be p or pp when anyone is singing, and marked

louder and regularly punctuated by Beethoven’s distinctive accented

dynamics (sfp and fp) when he wants the orchestra

to be more prominent.

The primary responsibility for bringing this Fidelio to

life, therefore, fell on the singers. The Princeton Festival casts solidly and

this year it assembled seven vocalists, each of which is the model of the

modern American singer. Armed with degrees from top conservatories, competition

awards, and experience in young singers’ programs, most are now in their

30s, working their way up in a tough profession. At major houses like the MET,

they sing comprimario roles or cover more established

colleagues; at regional companies, they sometimes assume lead roles. Most also

do concert or Broadway work, and several have foreign experience.

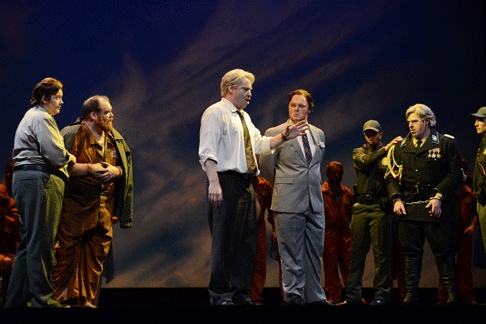

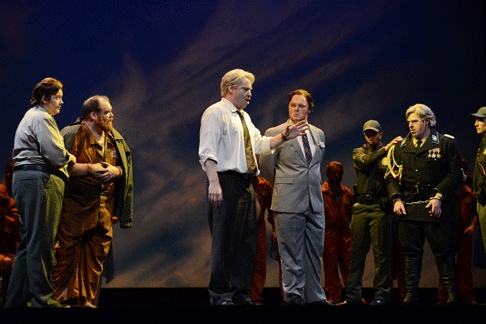

(L-R) Marcy Stonikas (Leonore/Fidelio), Noah Baetge (Florestan), Gustav Andreassen (Rocco), Cameron Jackson (Don Fernando), Joseph Barron (Don Pizarro)

(L-R) Marcy Stonikas (Leonore/Fidelio), Noah Baetge (Florestan), Gustav Andreassen (Rocco), Cameron Jackson (Don Fernando), Joseph Barron (Don Pizarro)

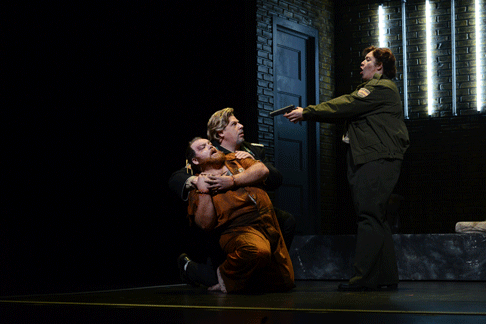

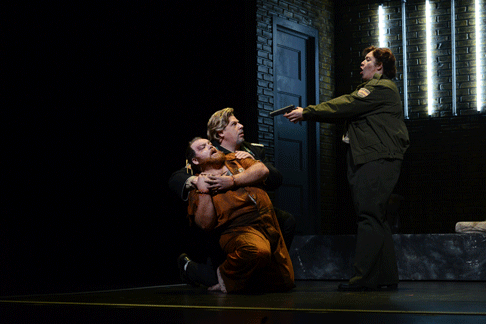

By far most impressive among them is Noah Baetge. From the first word of

Florestan’s Act II recitative—a striking messa di

voce from pianissimo to forte and back on

“Gott!”—he displayed a voice of potential greatness. I have

rarely heard any tenor, live or in recordings, so effortlessly navigate

Beethoven’s unforgiving heights, to which Baetge adds heroic brilliance,

a sweet timbre and spot-on intonation. A bit more weight in some swiftly moving

passages lower down and better German diction (especially spoken) would have

rendered this performance worthy of a major house. I have not heard such a

thrilling voice in live opera in Princeton since the young Lisette Oropesa

appeared a decade ago in Lucia di Lammermoor—a role she

reprises this fall at Covent Garden.

Raised in Chicago and now based (like Baetge) in Seattle, Soprano Marcy

Stonikas has sung Leonore at the Vienna Volksoper. She deploys a voice of

considerable weight with conviction. For lack of more freely soaring high notes

and warmer low ones, and a general cautiousness of utterance, the character of

Leonore never came entirely to life.

The rest of the cast sang with uniform professionalism. Norwegian-American

bass Gustav Andreassen made a solid Rocco, even without the warm bass, crisp

articulation and clear diction appropriate to his voluble paternalism. Soprano

Danielle Talamantes (a graduate of nearby Westminster College) and tenor

Michael Kuhn (who appeared in “A Little Night Music” last year in

Princeton) waxed passionate as Marzelline and Jaquino, even if somewhat they

lacked some smoothness and charm. (Kuhn, an experienced Broadway singer, did

act convincingly.) Pennsylvanian bass-baritone Joseph Barron, returning after

“Peter Grimes” last year, chewed the scenery as a truly villainous

Don Pizarro. Cameron Jackson, still attending graduate school in North

Carolina, presented a believable Don Fernando. The chorus sang lustily, with

fine solos from the two prisoners.

Marcy Stonikas (Leonore/Fidelio), Noah Baetge (Florestan), Joseph Barron (Don Pizarro)

Marcy Stonikas (Leonore/Fidelio), Noah Baetge (Florestan), Joseph Barron (Don Pizarro)

The Princeton Festival’s long-time stage director, Steven

LaCosse, set the action in modern Spain, with Florestan as a union

organizer, Rocco as an older prison warden, Marzelline as his daughter, Jaquino

as a janitor, Don Fernando as a prime minister in a fancy grey suit, and so on.

Some of the resulting dramatic action, especially in Act I, was remarkably

convincing to a modern audience.

While I deplore, for example, the modern habit of distracting audiences by

“staging” overtures and “entre’acts” behind a

scrim. (This is particularly annoying when the music from which one is being

distracted is a timeless Beethoven overture.) Yet I must admit that this

approach worked well: during the Fidelio overture, we saw

Florestan being arrested for holding a union meeting and during

the Leonore No. 3 we saw loved ones greeting the freed

prisoners one-by-one as they emerged from the subterranean prison. Both

stagings tastefully went dark at the recapitulation, giving music lovers their

moment, too.

Similarly impressive was the use of class distinctions to underscore

conflicts, as with Marzelline’s unwillingness to give Jaquino the time of

day apparently because he is a custodian. For the first time ever, I heard an

audience actually laugh at the comic interchanges in the first scene. And

amidst the concluding jubilation, I appreciated the conceit of the lead

characters giving brief TV interviews.

Otherwise the sets honed to the successful formula of opera at the Princeton

Festival: simple, suggestive, realistic and brightly lit. One suggestion for

the future. It is always worth the expense—especially in a hall like

Matthews Theater, with exceptionally harsh and cold sound—to create

acoustically resonant scenery. Above all, that means avoiding

“open” sets (scenery without backs, sides or a top), which project

substantially less vocal sound to the audience (up to 25% less, according to

some studies). This surely contributed to the persistent imbalance between

orchestra and singers—except in the case of Noah Baetge, a singer I hope

to hear again soon.

Overall, with this Fidelio Princeton Festival extends a

string of remarkably accomplished and successful operas—an impressive

achievement not least because each production receives only two performances.

The audience, which filled about ¾ of the hall, responded

enthusiastically.

Andrew Moravcsik