Erismena in Aix was an incredible feat, captivating its audience for nearly three hours, evoking a thunderous applause. Its dramatis personae seducing us with their airs and ariosos, their elaborate recitatives and a final madrigal sung by its two sets of lovers, four soprano voices interweaving with such sweetness that we too drowned in their eternal raptures of love.

It took a long time to get to that madrigal, but no one minded. Least of all, seemingly, the young artists who sustained a concentration of voice and word and line, and the suspended tension of outcome created by the insatiable thirst Aldimira had for lovers, the terrifying dream that haunted Erimante, the dalliances of servants, the discoveries of “real” identities (and so on and so forth). It was the youth and the charm and the excellent artistry of these artists that made the inanities of Venetian opera into high art and great entertainment.

This version of Cavalli’s masterwork was created by Argentine born, Swiss early music conductor Leonardo Garcia Alarcón with his continuos provided by his Cappella Mediterannea (last spring Mo. Alarcón created a version of Cavalli’s massive Giasone for the Geneva Opera). The continuos in Aix were rich indeed with the maestro seated at an organ with virginals atop, harpsichord, two cellos, a bass and three “pluckers” on a variety of instruments. Two violins and two wind players added a plentitude of additional colors for the concerted pieces.

There were always new combinations to support the complications on the stage — from the roughness of Baroque violins, the violence of the cornetti, the sweetness, then unleashed chirping of the flutes, the warmth of full ensemble, the thundering (intended) of the organ. It was a very busy pit, Mo. Alarcón conducting seated, standing, with one hand (the other always at a keyboard), with his head, with his body. It was concentrated, joyous music making.

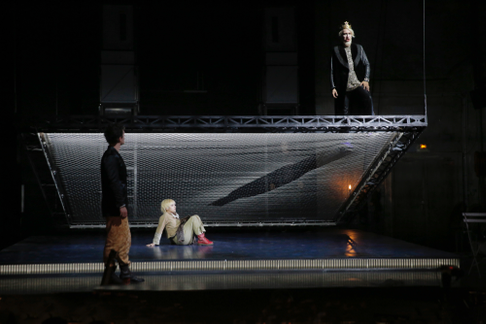

The platform

The platform

On stage there was nothing but a suspendible platform of transparent metal mesh, two elevated doorways, a canopy of suspended light bulbs and five or so cafe chairs from a junk pile somewhere. Think minimalism but do not think it was minimal. Moving these elements every which way as the situations changed throughout the evening was a monumental task. And there was a multitude of lightbulbs, some of which even knew to burst with a bang when there was a revelation down below!

The production requirements and accomplishments were formidable. From the “found” nature of the costuming (but indeed constructed given that no fuchsia suit the size needed to cloth the “skirt role” of the nurse could possibly exist, or the specific choice of fabric and sizes for the skirts worn by the male roles) to the make-up that added flashes of sparkle to the femme fatale Aldimira and the livid facial scar worn by Erimante’s lieutenant Diarte as examples of many.

There was no metaphor. The imagined story of pseudo-Roman history was told as written in this abstract, contemporary setting, French director Jean Bellorini moved his actors on and off the sometimes suspended platform, carefully established a space for each of the arias, changed his actors positions in direct dialogue to punctuate statement, and displaced them in a sudden blackout into a pool of light to utter an inner thought. Mr. Bellorini also masterminded the lighting that was of formidable complexity and huge effect.

The bows

The bows

This weighty production effort was effectively absorbed, even eclipsed by the individual performances. Italian soprano Francesca Aspramonte sculpted the title role disguised as a warrior in clear tone, making impressive use of the Italian rolled “r” to aggravate her chagrin (she has lost her lover Idraspe to Aldimira), Italian counter-tenor Carlo Vistoli brought sensitivity and strength to Idraspe (who finally, hours later, recognized Erismena). British soprano Susanna Hurrell as Aldimira negotiated her nymphomania with soprano-esque verve, Polish counter-tenor Jakub Jósef Orliński dazzled us with some spectacular breakdance move declaring his love for Aldimira. These four artists delivered the final, mesmerizing, four part madrigal.

Some of the most impressive singing of the evening was achieved by 23 year-old French mezzo Lea Desandre as Aldirmira’s maid Flerida and Italian baritone Andrea Bonsignore as Idraspe’s servant Agrippo. The man who lost it all but gains a daughter and an heir, the Median king Erimante was solidly sung and acted by Russian bass-baritone Alexander Miminoshvili. New Zealand tenor Jonathan Abernathey was the strong voiced, virile lieutenant to King Erimante, these the two male voiced male roles.

Not to neglect dwelling on the crowd pleasing accomplishments of the comic roles — the nurse, Alcesta, well sung and convincingly, even lovingly acted by British tenor Stuart Jackson, and the role of Idraspe’s friend Clereo Moro, sung in very beautiful voice and estimable charisma by American counter-tenor Tai Oney.

The program booklet included a two-page, small print synopsis of the story of the opera. No one but no one could have made heads or tails of it. This excellent production took it all in stride and made an evening of admirable, comprehensible and highly amusing theater.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Erismena: Francesca Aspromonte; Idraspe: Carlo Vistoli; Aldimira: Susanna Hurrell; Orimeno: Jakub Józef Orliński; Erimante: Alexander Miminoshvili; Flerida: Lea Desandre; Argippo: Andrea Vincenzo Bonsignore; Alcesta: Stuart Jackson; Clerio Moro: Tai Oney; Diarte: Jonathan Abernethy. Orchestre Cappella Mediterranea. Conductor: Leonardo García Alarcón; Mise en scène et lumière: Jean Bellorini; Décors: Jean Bellorini et Véronique Chazal; Costumes: Macha Makeïeff; Wigs and Make-up: Cécile Kretschmar. Théâtre du Jeu de Paume, Aix-en-Provence, July 7, 2017