An indignant sense of unjust usurpation was probably just as prevalent in

Hanoverian London - that is, among those Jacobites who sought to

re-establish a Stuart monarchy. But, despite the large map of Milan which

looms from the wall of the political headquarters in Jones’s production,

there is little sense of ‘specificity’ of geography or ideology. Instead,

we find ourselves in a mid-twentieth-century mobster-land - dimly lit,

ugly, bleak. Characters - a steadfast but resourceful wife; a conflicted

villain; a noble, self-knowing ‘deliverer’ - take precedence over locale or

period which, given the striking musical portraits created by Handel, is

fitting.

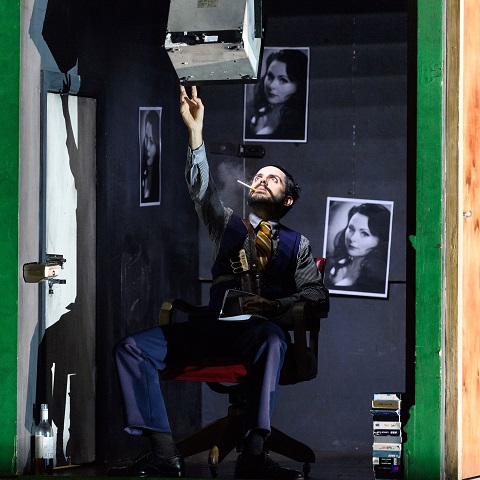

For Acts 1 and 2, Jeremy Herbert’s set divides the wide Coliseum stage in

two. Stage left is a dingy incarceration cell where Rodelina - whose

husband Bertarido, King of Milan, has been ousted from the throne by the

iniquitous Grimoaldo who nurtures amorous aims and claims upon his rival’s

wife - languishes in grief, with her son Flavio. The grimy prison houses an

array of surveillance cameras and telescreens worthy of an Orwellian

dystopia. In the panelled office of state, stage right, the supplanting

despots pour over the transmitted images of their captives with voyeuristic

slathering; when, that is, they are not eagerly destroying iconic images of

the rightful King and decorating the walls with their own visual

propaganda. The split stage is most powerfully deployed at the close of Act

2, when the reunited beloveds are forced to sing to each other, first

through a dividing wall, then separated by a central corridor, before the

rooms left and right slide torturously away from each other, cruelly

entrenching their severance. The emotional segregation of the characters is

further exacerbated in the final act, when horizontal partitions isolate

individuals with only their own emotional crises and inadequacies for

company.

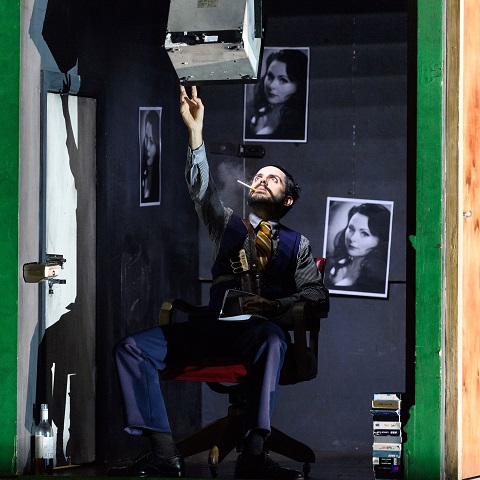

Rodelinda end of Act 2. Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

Rodelinda end of Act 2. Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

Rodelinda

has one of Handel’s least convoluted plots. Nicholas Haym’s libretto,

adapted from a text by Antonio Salvi, presents Rodelinda’s fidelity to her

‘dead’ husband (he has faked his own demise to both spy on his grieving

wife and surprise his usurpers), Grimoaldo’s inner conflict (he is torn

between genuine desire for Rodelinda and a lust for absolute power), and

Bertarido’s honour. There are a couple of ‘grotesques’: Eduige, Bertarido’s

sister, who is rejected by Grimoaldo, and the brutish thug Garibaldo who

makes overtures to Eduige in the hope of gaining the throne for himself. In

the end, ‘right’ triumphs over rapacity.

Jones (as revived by Donna Stirrup) and Herbert offer plentiful visual,

aural and choreographic details, with varying degrees of relevance and

effectiveness. Some will welcome and others lament the aural

verisimilitude: the door slamming, foot stamping, pained wailing that

punctures the exquisite music. The notion of fidelity which is at the heart

of the opera is represented visually by a recurring tattooing motif and

some blood-letting: one of the closing images of Act 3 is of a huge

forearm, tattooed in gilt with the name ‘Rodelina’, lying askew in the sand

beside a giant fist clutching a broken-off sword hilt: ‘Ozymandias’ meets Planet of the Apes.

Jones essays some humorous counterpoints to the prevailing tragic gloom,

but they don’t all hit the mark. During the overture, three turning

treadmills propel the characters into the dramatic maelstrom, but it’s not

so far from such cartoon capers to the farce of Keystone Kops. Indeed,

subsequently, when the loyal but ineffectual Unulfo (beautifully sung by

Christopher Lowrey), fleeing from his aggressors, spins and swirls along

and off the treadmill with the grace of a ballerina, one wonders if he’s

auditioning for English National Ballet.

Christopher Lowrey. Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

Christopher Lowrey. Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

Sometimes, mockery undermines a strong dramatic point, as when Flavio’s

rabid gesticulations present a violent charade to Grimoaldo which swerves

our attention from the fact that, in daring the tyrant to kill her son - an

act which will confirm his dastardliness but which she believes him too

cowardly to fulfil - Rodelinda proves herself an equal Machiavellian.

Similarly, when she dances a tense tango with Grimoaldo and then taunts

him, ‘I loathe you’, the bathos prompted a (surely unintended) chuckle. By

Act 3, when Unulfo is accidentally wounded by the imprisoned Bertarido and

staggers through the final act - ‘Don’t worry, it won’t be fatal’ - the

comic drollery has the upper hand over potentially tragic conflict. One

wishes that Jones had had faith that Handel’s own penchant for irony would

be sufficient.

The cast are, fortunately, superb, many reprising their roles from the

first run. Rebecca Evans captures all of Rodelinda’s dolorous grief and

self-examination, untroubled by the heights from which so many of Handel’s

phrases start, then fall lamentingly. She imbues her soprano with freshness

and warmth to convey the depth of her love for Bertarido, and their Act 2

duet is a musical and emotional peak of the performance.

Rebecca Evans. Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

Rebecca Evans. Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

Tim Mead surprised me with the impact and strength of his performance as

the exiled King; his always expressive countertenor seems to have found new

fullness and depth, and he persuasively communicated Bertarido’s sincerity

and self-belief. Bertarido’s aria of despair when he believes that

Rodelinda has forsaken him was utterly compelling, sung beneath the

fluorescent illuminations of a cocktail bar - the motif was perhaps a nod

towards David Alden’s 2004/05 Munich/San Francisco 1930s film noir

infused production which presented a similar neon sign, ‘Bar’, at the start

of Act 2, above seedy backstreets.

Juan Sancho and Tim Mead. Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

Juan Sancho and Tim Mead. Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

Juan Sancho was striking as Grimoaldo; though his tenor is quite light, he

made genuine the villain’s inner conflict - between his desire for power

and his desire for Rodelinda. The aria in which he reflects on his dilemma

- if he has Bertarido killed, he will retain his power but will lose all

hope of persuading Rodelinda to marry him; if he frees Bertarido, he will

lose both Rodelinda and, most probably, the throne - achieved the seemingly

impossible task of arousing some small sympathy for the rogue. Here,

though, one problem of Amanda Holden’s crisp translation was emphasised;

the English text is sometimes too sparse to convey the inferences of the

original Italian. In his self-doubt, Grimoaldo compares his complicated

torment to the simple life he imagines a shepherd to lead; the comparison,

and the lilting rhythms of the aria which suggest the peace offered by the

pastoral, are entirely authentic within an eighteenth-century context, but

the rather blunt translation raised an awkward laugh.

Juan Sancho. Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

Juan Sancho. Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

Susan Bickley’s Eduige was sparky and larger-than-life - a bit too Mrs

Slocombe (Are You Being Served) for my liking, but the

role was well sung. Neal Davies was a terrifically rough-edged Garibaldo

without ever sinking into pantomime mode. Actor Matt Casey is given a lot

to do, more than Handel probably intended, in the silent role of Flavio,

and almost suggested psychopathic tendencies equal to those of his captor.

Susan Bickley and Rebecca Evans. Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

Susan Bickley and Rebecca Evans. Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

Conductor Christian Curnyn guided his instrumentalists through an elegant,

attentive reading of the score - there was some lovely, prominent woodwind

playing - but it felt at little sedate at times; Act 2, in particular,

needed more dramatic impetus.

Handel provides the expected lieto fine, as all sing in praise of

the sun which warms the land and brings peace and harmony; but Jones,

characteristically, has one final twist up his sleeve. Whether you like

this production may well depend on whether you delight in such pouting and

piquancy; but, if you enjoy superb Handelian singing then you should get

yourself along to the Coliseum before the run finishes on

15th November

.

Claire Seymour

Handel: Rodelinda

Rodelinda - Rebecca Evans, Bertarido - Tim Mead, Flavio - Matt Casey,

Grimoaldo - Juan Sancho, Eduige - Susan Bickley, Garibaldo - Neal Davies,

Unulfo - Christopher Lowrey; director - Richard Jones, revival director -

Donna Stirrup, conductor - Christian Curnyn, set designer - Jeremy Herbert,

costume designer - Nicky Gillibrand, lighting designer - Mimi Jordan

Sherin, choreographer - Sarah Fahie, video designer - Steven Williams,

fight director - Bret Yount.

English National Opera, London Coliseum; Thursday 26th October

2017.