12 Feb 2018

Il barbiere di Siviglia in Marseille

Any Laurent Pelly production is news, any role undertaken by soprano Stephanie d’Oustrac is news. Here’s the news from Marseille.

Any Laurent Pelly production is news, any role undertaken by soprano Stephanie d’Oustrac is news. Here’s the news from Marseille.

Rossini’s grand old (1816) comedy took the stage just now in Marseille’s fine, old (1787) opera house in the form of a Laurent Pelly production.

Pelly’s black and white production premiered this past December at Paris’ Théâtre des Champs Elysees. France’s most read newspaper Le Monde dubbed it a Barber in “demi-deuil” (half-mourning) and somehow dug up hints of tragedy in the storm — a bewildered Rosina rushed across a blank dark stage, dead leaves flying. Laurent Pelly’s conceit was in fact black ink on white paper, huge sheets of blank musical score paper on which Figaro tried to write out Lindoro’s “Se il mio nome bramate” (If you wish to know my name). In due time, however, for its moment “L’Inutile precauzione,” as backdrop, was fully notated (wittily it was not with the actual tune).

It was a complex conceit, the singers filling in, virtually, the notes missing on the scenery, or maybe the old warhorse having been performed so many times that Mr. Pelly found its story irrelevant — thus Il barbiere di Siviglia is only music, or maybe Mr. Pelly’s was saying that Il barbiere is music, though we already know this. Music was indeed a useless precaution in this scheme of things Barberiana.

Or something.

To be generous the five black lines of the musical staff did serve to imprison Rosina who appeared behind them when a square opened on a white page wall creating her balcony.

Mr. Pelly deployed his choruses and ensembles in geometric patterns, dissolving movement into abstracted, repeated motions (like music notation) reinforcing the music score conceit (the chorus mimed unison violins for Lindoro’s “Ecco ridente in cielo,” then stormed in as police brandishing folding metal music stands. These events were just the tip of the iceberg — there are lots of duets, trios, quartets and quintets, and one more chorus — gentlemen in regimented concert formation, sheets of music on their folding metal stands. It was a masterwork of stage choreography.

The drunken soldier, Figaro in swing

The drunken soldier, Figaro in swing

It was a long evening at the Marseille Opéra, a very long evening. [One of the most charming evenings I have ever passed in a theater was Laurent Pelly’s La Périchole (Stephanie d’Oustrac) at the Marseille Opéra back in 2002.]

Conductor Roberto Rizzi Brignoli was determined to make Rossini’s comic masterpiece into something it is not — Mozart, with touches of Cilea. The Barber’s overture was a caricature of this oft concert-performed masterpiece, this maestro insisting on determined, very determined tempos and very shaped phrases. The opening oboe solo was so extended that you could feel the player’s face turning red. Missing from the entire evening was the joy of music making, the joy of singing and the release of musical spirit when a vocal line explodes into fioratura.

The only carry over from the Paris cast was to have been the Figaro of Florian Sempey, but the diseases of the season claimed veteran baritone Carlos Chausson’s Bartolo at the very last minute, thus Spaniard Pablo Ruiz [the opera singer, not the pop singer of the same name] from the Paris cast jumped in.

It is surely possible to say that young baritone Florian Sempey will be (probably is) the reigning Figaro of our day. Less a look-alike of an imagined young Rossini now than in his Pesaro Figaro in 2015 he once again succeeded in bringing perfect Rossinian spirit to this comic hero. Mr. Sempey has facile, graceful movement on stage, and facile command of Rossini’s vocal requirements, singing in strongly focused, beautiful tone. Of infectious energy Mr. Sempey's Figaro in this production had no easily apparent context, thus there was no dramatic focus and this rendered his fine performance somewhat overbearing.

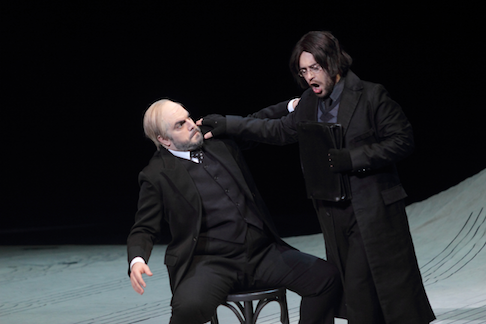

Bartolo and Basilio

Bartolo and Basilio

There can be no argument that Stephanie d’Oustrac can create fascinating character, witness her recent successes as Carmen in wildly different productions. Certainly her Rosina in this production is a masterpiece of character — a sort of “valley girl” or whatever the French equivalent is. La d’Oustrac’s Rosina is more than anything else fun, and she is not a bit frightened by the prospect of marrying Bartolo. Her “una voce poco fa” was so inflected with personality that you forgot it was being sung. Although her performance was vocally secure and virtuoso indeed, I did miss a purely sung Rossini Rosina.

With the powerhouse conducting, the overwhelming staging conceit, and the surpassing performances of Mme. d’Oustrac and Mr. Sempey the balance of the cast struggled to make impression. Lindoro was ably if softly sung by French tenor Philippe Talbot, Spanish baritone Pablo Ruiz was an able, persuasive Bartolo, Young Italian bass Mirco Palazzi was Basilio, paired in appearance with Lindoro, a subtle casting touch. Annunziata Vestri was a lively, big voiced Berta and did make an impression. Fiorello was well presented by local Marseille singer Mikhaël Piccone.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Rosina: Stéphanie d’Oustrac; Berta: Annunziata Vestri; Comte Almaviva: Philippe Talbot; Figaro: Florian Sempey; Bartolo: Pablo Ruiz; Basilio: Mirco Palazzi; Fiorello: Mikhaël Piccone; Un Ufficiale: Michel Vaissiere; Ambroggio: Jean-Luc Epitalon. Orchestre et Chœur de l’Opéra de Marseille. Conductor: Roberto Rizzi Brignoli; Mise en scène, décors, costumes: Laurent Pelly; Lighting: Joël Adam. Opéra de Marseille, February 9, 2018