16 Apr 2018

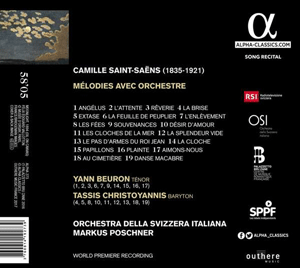

Camille Saint-Saens: Mélodies avec orchestra

Saint-Saëns Mélodies avec orchestra with Yann Beuron and Tassis Christoyannis with the Orchestra della Svizzera Italiana conducted by Markus Poschner.

Saint-Saëns Mélodies avec orchestra with Yann Beuron and Tassis Christoyannis with the Orchestra della Svizzera Italiana conducted by Markus Poschner.

Though the songs for voice and piano have previously been recorded, this is the world premiere recording of the full orchestral versions, taken from a performance in Lugano in 2016 sponsored by Palazzetto Bru-Zane, champions in the promotion of French repertoire. In this landmark issue, distributed by Alpha classics, nineteen of the twenty-five orchestral songs in the composer's catalogue are included.

Saint-Saëns was only thirteen years old when he wrote L'Enlèvement, in 1848, first for piano and voice, orchestrating it very shortly afterwards. Aimons-nous was completed seventy years later, two years before the composer's death. Though Saint-Saëns’ reputation has been based on his larger works, he had a lifelong commitment to song. This is particularly significant given the dominance of Grand Opéra and symphonic works in mid-19th century France. Berlioz's Les nuits d'été was initially composed for voice and piano, the orchestrations only completed in 1856. Concert performances tended towards programmes of operatic arias or works for piano.

By orchestrating his songs, Saint-Saëns was making an artistic statement. In 1876, he wrote "The Lied with orchestra is a social necessity. If such things were available, people would not always be singing operatic arias in concerts, which often make a pitiful effect in those surroundings". As Sébastien Troester writes in his notes, "incongruous accents and faulty ceasuras and enjambments" could occur in popular works by composers whose native language was not French. Thus Saint-Saëns created orchestral song as art song as serious concert music, a synthesis of voice and symphony, building on the riches of French poetry. Orchestral form also allows for exotic colour and sensuality, making use, as Troester writes "of ancient modes, of ostinato rhythms that create a sensation of languor, of vocal melismas", distinctive and very Belle Époque.

The performances here are superb, the epitome of idiomatic style. Despite its richness, the beauty of Saint-Saëns music lies in its purity. The ornamenations exist to amplify ideas and structure. Poschner and the orchestra keep, the colours clear. "Hollywood excess" is not the way to go Elegance lies in articulation. Beuron and Chritoyannis phrase and shape so that the words can be heard clearly, without exaggeration, but with natural, flowing flair.

Angélus, to a poem by Pierre Aguétant (1890-1940) begins with the tolling of a bell, followed by shimmering strings. "Les clochers, souverains du soir", sings the tenor Yann Beuron, pacing the line with the deliberation of medieval chant. In the monastery, the monks are singing Angelus, and outside, the shepherds hear the sound on the air as if the wings of God were rushing past. Similar frisson in the strings introduces L'attente (Victor Hugo) but here the pace is swift, barely able to contain excitement. "Climb, squirrel, up the oak.... eagle, rise from your eyrie!" In Rêverie (Hugo) phrases in each strophe are repeated, with slight variation, the orchestra echoing the vocal line, the effect as lovers entwined. Beuron's wonderful diction warms words tenderly: "Mon coeur, dont rien ne reste, L'amour ôté ! "

Extended orchestral colour pays off handsomely in songs like La Brise from Saint-Saëns' Mélodies Persanes op 26 (1870) to a text by Arrmand Renaud (1836-1895). Swaying string lines suggest exotic dance, against dance rhythms based on percussion and bells. A clarinet suggests "oriental" woodwinds. The vocal line (Tassis Christoyannis) equally agile, with long, curving phrases. Similar felicities in Extase (Hugo) where the text itself repeats and changes in intricate patterns. Woodwinds "mobile et tremblante" suggest the falling leaves in La feuille de peuplier (Mme Amable Tastu, 1795-1885). A lilting woodwind melody lifts L'Enlèvement (Hugo) raising the song to heights few composers aged only 13 could hope to achieve. Woodwinds again in Les Fées (Théodore de Banville 1821-1891) suggest the movement of swallows in flight, as the vocal line soars upwards. The vocal line (Beuron) in Souvenances (Ferdinand Lemaire 1832-1879) dips gracefully, garlanded by the orchestra.

Flutes and strings shimmer in Les cloches de la mer to a text by the composer himself, but a much darker, more dramatic mood emerges, the orchestra surging tutti, suggesting the depths of the ocean. La splendeur vide from Mélodies Persanes op 26. describes "un merveilleux palais" filled with jewels (vividly evoked by the orchestra), but the glory masks despair. "Plus je suis tombeau", sings Troyannis, his voice descending to near whisper. The full orchestra surges again, horns ablaze, in Le pas d'armes du roi Jean (Hugo) a long ballad where the singer (Troyannis) has to characterise the different figures in the poem, while marking the short, clipped phrases in the text.

More mock medievalism in La cloche (Hugo) where Beuron floats the last line "dans le ciel" so it dissolves into silence. This prepares us for the fluttering delicacy of Papillons (Renée de Léché) where a pair of flutes duet, darker winds and strings adding texture. The song ends abruptly : butterflies die. Thus Pliante (Tastu), (1918) with strong chords of dark portent. "Ô monde ! Ô vie ! Ô temps!". In contrast, though written in the same period, Aimons-nous (Banville) where lovers embrace, peacefully, in death. In Au cimetière again from Mélodies persanes the two groups of strings are plucked, then bowed, suggesting the beat of a pulse and sighs of breath. The mood is hushed, yet enraptured. To conclude, Danse macabre op 40 but with a difference. This was originally written for voice and piano in 1872, then revised for violin and orchestra. Here, voice, violin and orchestra come together. It's a treat ! Christoyannis sings "zig-a-zig-za-zig le mort en cadence". Violin and voice locked in sinister dance. Méfistofeles having a laugh. Truly "et vive la mort et l'egalité!"

Anne Ozorio