In 2016 director Daisy Evans invited us to enter the creative processes

involved in staging and performing Henry Purcell’s

The Fairy Queen

- “we’re creating it as we go along” - presenting riotous rehearsals during

which luvvies, divas and techies roamed around a stage littered with

lights, ladders and electric leads. Musicians hunted for their seats,

soloists for their scripts, and the entire ensemble seemed in search of a

production. Last year, Evans offered a

‘King Arthur for the Brexit Age', re-ordering the score, discarding Dryden’s original text entirely and

replacing the poet’s allegorical obfuscations with what she described as “a

stage-invasion protest” in which opposing factions of Brexiteers and

Remainers offered “their perspective on the current stage and meaning of

British identity”. Brechtian flip-charts reminded us of the work’s

‘relevance’, the final poster bluntly stating, “The Barbican - Today”.

Nahum Tate’s libretto for Purcell’s three-act tragic opera, Dido and Aeneas, which was derived from the poet’s own play, Brutus of Alba or The Enchanted Lovers and various

translations of Book IV of Virgil’s Aeneid, might also seem to

offer scope for similar ‘modern, political intervention’. Certainly, there

has been much speculation about the opera’s engagement with the crises of

the final years of the Stuart monarchy. The Prologue, for which the music

is lost, might be thought to allude to the Glorious Revolution of 1688 with

Phoebus and Venus representing those embodiments of the new political

order, William and Mary. After all, in Act 1 the chorus celebrate: “When

monarchs unite, how happy their state,/They triumph at once o’er their foes

and their fate.” Then again, the opera’s tragic account of a Prince’s

desertion of a Queen would surely have made for a less comfortable court

entertainment. Moreover, in a poem written in 1686 Tate had alluded to

James II as Aeneas, intimating that his abandonment of Dido (a symbol of

the nation) was a result of his duping by the evil Sorceress and her

witches (signifying Roman Catholicism). Was Tate covertly warning William

III not to mistreat his English queen and nation?

Thomas Guthrie. Photo credit: Theresa Pewal.

Thomas Guthrie. Photo credit: Theresa Pewal.

The scholarly debates have engaged with multifarious musical and

extra-musical factors - literary, historical, sociological, political. And,

when I ask director Thomas Guthrie about his plans for the performance of Dido and Aeneas that the

Academy of Ancient Music

will present in the Barbican Hall on 2nd October, he explains his

fascination with the history of the literary treatment of Dido -

particularly Ovid, Virgil and then, in the sixteenth century and beyond,

Marlowe and others - and how that’s been reflected in the way the story has

been used politically, especially in reference to Elizabeth I. “I find her

especially useful in fleshing out and understanding the character of Dido

in the opera - I think it will be a real key for us. I’ve found Deanne

Williams’ article ‘Dido, Queen of England’,

[1]

particularly helpful: “Elissa dies tonight, and Carthage flames tomorrow!”

The idea of celibacy being a necessity for her, despite huge political

pressure to marry in the state’s interests, precisely to defend her

‘marriage to the state’, possibly provides answers - or at least a context

- to the very real tragedy of Aeneas’ change of heart, the subsequent sense

of betrayal Dido feels, and her suicide. I think this is at the heart of

it.”

’The Sieve Portrait’ by Quentin Metsys the Younger (c.1583; British Library Collection; Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena, Italy/Bridgeman Images). This portrait of establishes a connection between Elizabeth I’s virginity and England’s military power. The sieve represents both the Queen’s chastity and her discerning moral judgement. The pillar to the right of Elizabeth depicts scenes from the Aeneid, including Dido’s first meeting with Aeneas and her suicide.

’The Sieve Portrait’ by Quentin Metsys the Younger (c.1583; British Library Collection; Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena, Italy/Bridgeman Images). This portrait of establishes a connection between Elizabeth I’s virginity and England’s military power. The sieve represents both the Queen’s chastity and her discerning moral judgement. The pillar to the right of Elizabeth depicts scenes from the Aeneid, including Dido’s first meeting with Aeneas and her suicide.

Thomas also makes it clear that he inclines to a “less is more” approach

and that musical values will be paramount. His work always displays a

genuine commitment to new ideas and to challenging the audience but he

emphasises that while he aims to make a work feel “fresh and relevant” he

does “insist that the music and the storytelling are the most important

elements”: “I try to inspire the audience to engage in a critical way in

order to achieve good theatre. It’s not a matter of telling them what to

think or announcing ‘look how clever I am’; you have to invite them to

imagine for themselves. To encourage them to make their own pictures that

resonate with their own tastes, experiences and memories.”

Thomas points out that there are many questions unanswered, and often

unasked, about Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas. Indeed, the plot is

characterised by ambiguity and evasion. How does Dido die, for example?

Thomas comments that he does not think that the means of suicide is

particularly important: “A decision of course has to be made here - but it

is more a question of understanding why, and not settling for a

purely ‘heartbroken crossed lover’ assumption, which is common, and seems

too sentimental and shallow to me.”

I raise a further issue which has troubled commentators, whether Dido is

chaste - a question posed with surprising directness by Charles Perrault:

‘What had that Piety of Father Aeneas to do in the Cave with Dido Queen?’

[2]

Thomas replies: “Again, I think it’s clear from the classical sources and

then from Aeneas himself in Tate’s libretto (‘one night enjoyed’) that she

has not been chaste; and, the shame and betrayal to Carthage that she then

feels - after the sacrifices one presume she has made - are then more

understandable. To me one of the biggest unanswered questions centres

intriguingly around the Second Woman’s aria, ‘Oft she visits this lone

mountain’. Why has she sung this strikingly inappropriate song as an

entertainment at the grand state ‘betrothal picnic’? Or, who has put her up

to it, and why? Belinda is Dido’s closest ‘member of staff’; a

lady-in-waiting, a confidante, but also a go-between. One can only imagine

the pressure on her to snap the queen out of her apparent crisis/paralysis

when she sings her first, ‘Shake the cloud from off your brow!’ - in the

presence of the entire court. Matters of government must be pressing:

famine, threat of invasion. How long has it been since Dido has made a

public appearance? And, as a woman, she must want to be seen to be able to

keep any apparent overly emotional behaviour under control. Is Belinda

warning Dido by instructing the Second Woman to sing this particular song,

with its ominous, violent and well-known ending? Or, is she warning Aeneas,

and if so, why?”

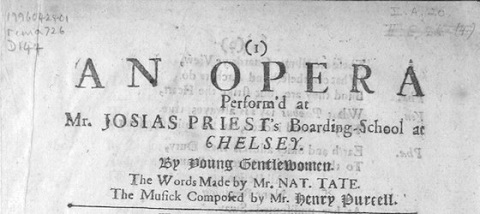

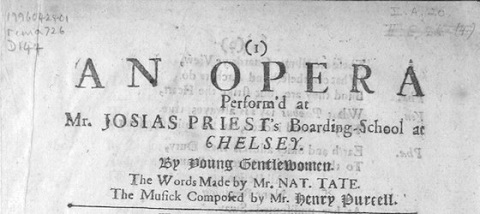

The first page of the libretto of Dido and Aeneas printed for the Chelsea school performance (detail). From the collection of the Royal College of Music.

The first page of the libretto of Dido and Aeneas printed for the Chelsea school performance (detail). From the collection of the Royal College of Music.

Then there is the problem of ‘the sources’. There is no autograph score,

and the so-called Tenbury College manuscript (now in the Bodleian Library),

which is generally considered to be the ‘best’ source available, was made

at least half a century after the first performance of the work and lacks

some music alluded to in the Chelsea libretto. The first known performance

of the tragic opera is that given at a girls’ boarding school in Chelsea

some time before December 1689 (when Thomas D’Urfey’s spoken epilogue was

published in his New Poems), and for a long time it was

assumed that Purcell had composed his opera for the young ladies of

dancer-choreographer Josias Priest’s educational establishment.

Subsequently this theory has been challenged: allusions in the Prologue and

Epilogue hint at a spring-time premiere, and some scholars have suggested

that, on stylistic grounds, the opera could have been composed by 1685, or

even earlier. Dido and Aeneas was certainly influenced - in its

broad structure, use of dance and dramatic choral roles, and

arioso-recitative idiom - by John Blow’s Venus and Adonis

(c.1683), which had been performed privately at the court of Charles II and

then adapted for Priest’s school in April 1684, and a similar performance

history would account for discrepancies between the extant libretto for the

Chelsea performance and the earliest surviving score which includes a

baritone Aeneas as well as countertenor, tenor and bass chorus parts.

Bryan White’s discovery of a copy of letter dated 15th February 1688/9

written by one Rowland Sherman, a merchant with the Levant Company in

Aleppo, to his friend and fellow merchant, James Piggott, in London, seemed

to resolve some of the controversies relating to the date and context of

the first performance and the original existence of instrumental music now

lost. Sherman asks for news of the London cultural scene, specifically: ‘If

Harry has sett to the Harpsechord the Symph[ony] of the mask he made for

Preists [sic] Ball, I should be very glad of a coppie of it. There's

another Symph[ony] in the same mask I think in Cb in the 2d p[ar]t is a

very neat point th[a]t moves all in quavers. if he's applyed th[a]t to the

harpsechord, ’twould be very acceptabl too.’

[3]

A portrait of Henry Purcell (c.1680).

A portrait of Henry Purcell (c.1680).

Yet, Dido and Aeneas is richly equivocal and is unlikely ever to

divulge all its secrets. Thomas Guthrie has frequently made use of puppets

and masks in his work, and I ask the director what led to his interest in

puppetry and whether he plans to make further use of them in his

exploration of Dido and Aeneas? Thomas explains that his interest

was initially sparked when he was working with I Fagiolini in a

2001 production of Purcell’s Indian Queen directed by Peter

Wilson. He remembers that bass-baritone Matthew Brook, “such a natural

actor”, sang in the production, and that it was Matthew’s particular use of

a puppet in ‘Ye twice ten hundred deities’ that inspired his own subsequent

staging of Winterreise with pianist Gary Cooper.

Thomas comments that the puppets must “work within and maintain the

integrity of the musical setting” and must not be “an interference”. His

staged Winterreise impressed the critics - in the words of one

reviewer, ‘puppet and singer-animator become one’ - and he explains that,

while he is not ever 100% convinced by or pleased with every aspect of his

work, “this production sought, by use of the puppet, to unlock the

storytelling and give opportunity for insight and freshness, but keep the

music-making integrated, which, despite its other faults, I think it did.”

“Puppets will only work if the audience are on board, if the puppets invite

the audience into the work. This can create a moment of magic, of wonderful

theatre.” Puppets are often symbolic - in Asia, rites of passage, birth,

marriage and death, are traditionally marked by puppet performances - and

Thomas stresses that it is important that the audience should be made to

believe in the purpose of the puppets within the theatrical context. He

modestly professes that, though he has studied and taught puppetry, he is

“not absolutely a 100% master of the art!” but adds that, “‘if you can hold

a teddy bear up to a child - and convince the child of its reality - then

you certainly have the basic skills to work a puppet. Not everyone has this

instinct, actually, but if you can do it, then good basic

puppetry, though a great and true craft, is at least within your grasp.”

Christine Rice. Photo Credit: Patricia Taylor.

Christine Rice. Photo Credit: Patricia Taylor.

In 2016 Thomas produced a concert staging of Dido and Aeneas with

the young singers of the early music ensemble Sestina, musicians

from Original Instruments and dancer/choreographer Bridget Madden,

a production which travelled to three venues of differing size and

environment - the Ulster Hall in Belfast, Londonderry’s The Glassworks and

The Church of the Sacred Heart in Newry. At the Barbican Hall, the role of

the Carthaginian Queen will be taken by Christine Rice, with whom Thomas

was a fellow student, and the director explains that during the eleven-day

rehearsal process the need to tell a story through music will be uppermost;

ideas will be explored, shaped by Rice’s own interpretation, and that of

Rowan Pierce, who will sing the role of Dido’s companion Belinda, Neal

Davies who takes the part of the Sorceress, and Ashley Riches who will

perform Aeneas. Things that don’t ‘work’ will be discarded. “The singer

needs to be the person working the puppet, communicating the idea; it won’t

work if there is a puppeteer … I want to make the audience ‘shift’ in their

engagement with the opera, to feel guilt!”

One issue that Thomas notes must be addressed when planning any performance

of Dido and Aeneas is the question of which compositions to

programme alongside the opera. At the Barbican Hall, the first half of the

concert will present a ‘funeral for the late Queen of Carthage’,

accompanied by other works by Purcell. The opera will, then, essentially be

a flash-back, taking us ‘behind the scenes’: we will see the characters

behave in certain ways before the funeral, perhaps intimating answers to

some of the opera’s conundrums.

Thomas concludes, “Purcell may seem ‘simple’ but his compositions invite

interpretation: and, he always gives more than he needs - that is

the nature of his genius. And, it’s why we delight in his music so much: he

gives much more than is needed to be ‘great’. So, we must not distract from

this, but celebrate it.”

At the close of Purcell’s opera, Dido bids her unforgettably poignant

farewell, “Remember me, but ah! forget my fate.” In this tragic gesture,

Purcell poses one final question: just how should we remember

Dido, Queen of Carthage? What does she represent? Perhaps we will find some

answers at the Barbican Hall on 2nd October …

Dido and Aeneas

: A funeral for the Queen of Carthage, Academy of Ancient Music,

Barbican Hall, 2nd October 2018.

Claire Seymour

[1]

Deanne Williams, ‘Dido, Queen of England’, ELH 73.1 (2006): 31-59.

[2]

In Parallèle des anciens et des modernes, 4 vols. (Paris,

1688-97).

[3]

Bryan White, ‘Letter from Aleppo: Dating the Chelsea School

Performance of Dido and Aeneas’, Early Music,

37/3 (2009): 417-428.