Of course, the debates are complex and the contexts diverse and often

starkly different. But, English Touring Opera’s production of Handel’s

Radamisto, currently touring the UK and visiting

cities from Durham in the north to Exeter in the south, seems to suggest

otherwise. Director James Conway’s production does not update the action,

does not consciously seek modern ‘relevance’, respects the score (though

there are some judicious cuts, which ensure that the audience’s stamina is

not over-taxed), and tells the story straight and true. In so doing,

Conway, aided by an accomplished cast, makes the historical dramatically

and emotionally immediate, and ‘real’.

Radamisto

, which premiered at the King’s Theatre on 27 April 1720, was Handel’s

first full-scale opera for the new Royal Academy of Music, and the latter’s

second production. The anonymous libretto (sometimes accredited to Nicola

Haym) was an adaptation of D. Lalli’s L’amour tirannico, o Zenobia (Venice, 1710), which itself drew on

a byway of Roman history as related by Tacitus in his Annals of Imperial Rome.

Characteristically, this opera seria text throws spousal devotion,

patriotic duty, tyrannical lust and tested loyalties into the dramatic

bear-pit. It is the female characters - the abused and long-suffering

Polissena, wife of the Armenian King Tiridate, and Zenobia, the wife of

Tiridate’s brother-in-law, Radamisto, whom the narcissistic, infatuated

Armenian hothead desires as much as he craves the Thracian Radamisto’s

throne - who, as emblems of faithfulness and fortitude, lead us through

cruelties and moral quagmires to resolution, reconciliation and

reassurance. And, Conway, fittingly foregrounds this female duo, providing

motivation and moral focus in the face of some of the libretto’s non

sequiturs and nonsensical sequences.

John-Colyn Gyeantey (Tigrane), Andrew Slater (Farasmane). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

John-Colyn Gyeantey (Tigrane), Andrew Slater (Farasmane). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

While Radamisto epitomises romantic loyalty and filial duty, the other male

characters prove feckless, flimsy or, in the case of Farasmane, Radamisto’s

deposed father, weakened by imprisonment and humiliation. The character of

Fraate - Tiridate’s brother, who has also desired Zenobia and who

originally facilitated some of the plot mechanisms and motivations - was,

when the opera was revived in December 1720, revised by Handel and then

subsequently eliminated, so Conway’s decision to excise this rather

one-dimensional role seems sensible.

Designer Adam Wiltshire’s set is economical: starkly lit by Rory Beaton

within a surrounding blackness - thereby isolating and sharpening the

characters’ ethical dilemmas and defects - archways and porticos, ramparts

and rockfaces, and some splendid costumes, provide visual definition of

time, place and aesthetic. In the apparent absence of stage-hands, the

characters themselves swivel and slide the large set-pieces: twice William

Towers, immediately after delivering one of Radamisto’s stamina-taxing

arias, had to find a bit more breath and strength to shift a heavy arch or

wall.

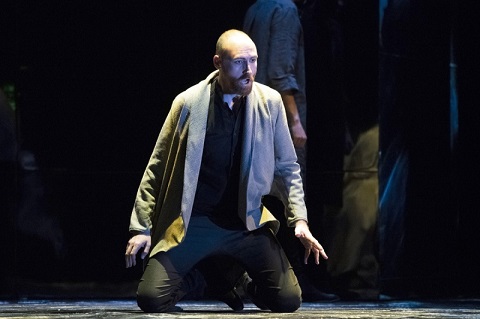

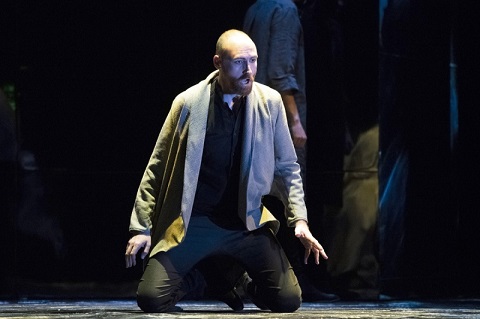

William Towers (Radamisto), Katie Bray (Zenobia). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

William Towers (Radamisto), Katie Bray (Zenobia). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Beaton shines heightening white spotlights on characters as they plunge

emotional depths in their arias, but also makes effective use of colour.

Polissena’s bravura ‘Dopo l’orride procelle’, which ends Handel’s first of

three acts, was set against a screened backdrop of a fateful sky which

transmuted from grey-blue, through lilac and purple, to portentous red. In

Act 2, a towering entrance opening, slashed into the prevailing black,

glowed a fiery orange. And, there were a few scenic effects which surprised

the audience in Snape Maltings Concert Hall: such as when the fleeing

Radamisto and Zenobia seemed to climb into the back-telescreen,

which proved to be not two- but three-dimensional, and scampered agilely up

the precarious mountain face from which Zenobia would throw herself in

suicidal despair.

The title role was originally designed for a low soprano and was sung by

Margherita Durastanti, but for the December 1720 production Handel made

significant changes to Radamisto to suit the new, largely Italian

cast who had arrived in London that year, and the role of the Thracian

prince was taken by the castrato Senesino. Durastanti was renowned for her

wide emotional range, Senesino for the power and sweetness of his voice,

and the refinement of his ornamentation. I found Towers’ Radamisto a little

undefined dramatically at the start - ‘Perfido, di a quell'empio tiranno’,

sung in response to Tiridate’s threats to destroy Farasmene’s city if he

does not relinquish his throne, and Zenobia’s self-sacrificing submission

to Tiridate, might have been more assertive and confident - but the

countertenor ‘grew into’ the role. ‘Ombra fa’ was both technically assured

and inspired our sympathy - all the more so as Towers had to deliver his

show-piece perched upon a precipitous ledge. The duet between Radamisto and

Zenobia which ends Act II was particularly affecting.

Ellie Laugharne (Polissena, centre). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Ellie Laugharne (Polissena, centre). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Ellie Laugharne endowed Polissene which dignity and presence, phrasing the

plaintive ‘Sommi dei’ beautifully and singing with lovely expressive tone

and shading. She sometimes seemed a little underpowered in the more rapid

passagework and ‘Sposo ingrato’, in which the Queen challenges her abusive

husband having previously saved him from her brother’s murderous wrath, was

accurate but rather light.

John-Colyn Gyeantey performed the part of Tigrane, Tiridate’s

conscience-stricken but gutless henchman, a role that was originally taken

by soprano Caterina Galerati and which is still frequently sung by a

soprano. Gyeantey’s characterisation was a little pale, but he made a fair

attempt to convey Tigrane’s sincerity as he equivocated between his duties,

passions and morals. The tenor was at his best in the slow passages which

offered spaciousness to allow the beauty of his soft-grained tone to shine.

As his Act 3 aria, ‘So ch’è vana la speranza’, showed, he can give poise to

an emotional moment, but Gyeantey’s tenor lost definition and impact in the

quicker passages and when the recitative was required to carry the drama

forwards.

Katie Bray (Zenobia), Grant Doyle (Tiridate). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Katie Bray (Zenobia), Grant Doyle (Tiridate). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Baritone Grant Doyle blustered appropriately as the psychotically

egotistical Tiridate, reminding us that there are far too many such

hot-headed narcissists in positions of political power today - Conway

describes the Armenian king as ‘perverted by his own unbridled will’ - but

occasionally sounding a little too tonally coarse. Andrew Slater conveyed

Farasmane’s dignity and moral stature as the deposed Thracian monarch was

man-handled around the stage.

The production truly came alive, though, when mezzo-soprano Katie Bray gave

vivid voice to Zenobia’s principled utterances and noble passions, her

scything power and richly coloured nuance sharply etching Zenobia’s

firmness of temperament and political presence. Bray displayed deeply

considered expressivity, too, in ‘Quando mai’, singing with tenderness and

pathos.

Radamisto

is bound to leave the audience with several unanswerable questions. Why

does Polissena continue to love Tiridate despite his vicious tyranny and

heartlessness? Why does Tridate vacillate so spinelessly? Why does Zenobia

throw herself off a mountain peak and then re-appear unscathed? Though

Conway tells the tale straight he can’t overcome all of the libretto’s non

sequiturs and nonsenses: the rapid climactic sequence at the end of Act 3

in which attempted rape is followed by thwarted double-murder, after which

the apparently dead Radamisto revives himself, and which concludes with

Tiridate’s personality-flip and a hastily constructed lieto fine

raised a few chuckles in Snape Maltings, but that’s probably the fault of

Handel’s libretto rather than directorial misjudgement.

Peter Whelan conducted the cast and the Old Street Band from the

harpsichord, the latter improving as the proceedings progressed: after a

slightly murky and dull overture, later we heard much more of the bright

colouring of Handel’s score as flute, oboe and horns made sympathetic

contributions to the drama. The continuo group was elegant led by Whelan

and he was complemented by some gracious theorbo playing from Toby Carr and

a lovely clear line from cellist Gavin Kibble. Whelan pushed the action

swiftly but not precipitously forwards, and the overall result was visual,

vocal and dramatic clarity and cohesiveness.

If only the relationships between the three parts of the triple bill which

was presented the following evening had been so clear. When I spoke to

Thomas Guthrie

recently, prior to his production of

Dido and Aeneas

at the Barbican

, he observed that one issue that must be addressed when staging Purcell’s

opera is the question of which compositions to programme alongside the

opera. Guthrie chose to present a ‘funeral for the late Queen of Carthage’

accompanied by other music by Purcell in the first half of the performance,

so that the opera functioned as a flash-back, taking us ‘behind the

scenes’. Conway and the other two directors presenting this triple bill

have prefaced the Carthaginian Queen’s tragic demise with Giacomo

Carissimi’s oratorio, Jonas, and I Will Not Speak ( Io tacerò) - a sequence of Carlo Gesualdo’s madrigals and

Tenebrae responses, interspersed with readings of poetic and religious

texts.

Seeking a link between these three items (beyond the general concerns with

fate and faith that they might be thought to share), I turned to conductor

Jonathan Peter Kenny’s programme article introducing Carissimi, but could

find nothing to guide me other than the tentative hypothesis that, since

Pepys had recorded his admiration for the Italian composer’s music in his

diary in the late-seventeenth century, and the latter’s music had been

copied into English manuscripts such as those preserved at Christ Church

Oxford, then, as Purcell had made his own copies of works by Monteverdi and

Cazzati, he ‘must surely have seen the examples of Carissimi’. Perhaps; but

if so, with what effect, and to what end here?

Carissimi’s Jonas is one of the oratorio volgare (in

Italian, as opposed to the oratorio latino, in Latin) that he

composed for performance before the religious elite in the Santa Crocificio

Oratory in Rome. Carissimi composed fifteen or so such works, labelling

them historioe: that is, they presented narrative

accounts of episodes drawn from the Bible - here, Jonah’s encounter with

the whale - in which drama is created by the juxtaposition of

varied musical forms - choral narration, madrigalian songs and duets, a

solo lament, instrumental episodes - and language, homophony alternating

with imitation.

Jorge Navarro-Colorado (Jonas). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Jorge Navarro-Colorado (Jonas). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

That master of the genre, George Frideric Handel, borrowed from Carissimi

in some of his own oratorios. In recent times we have become used to seeing

some of the latter staged, and here director Bernadette Iglich offered an

attempt to impose visual and kinetic ‘theatre’ on music which has its own

inherent drama. The eight performers, dressed in drab-coloured tunics and

representing the ‘wicked’ community of Nineveh, moved with ritualistic

solemnity around an unidentifiable column amid a blackness worthy of the

leviathan’s belly, reflecting on faith and doubt.

The most obviously ‘dramatic’ incidents the biblical tale seem of little

interest to Carissimi, though he does provide a colourful, explosive

storm-scene which was vibrantly played by the Old Street Band. The

composer’s focus is instead the doubts and equivocation of the protagonist.

Jonah’s aria of supplication from inside the belly of the whale is the

expressive climax, and it was beautifully sung by Jorge Navarro Colorado,

the refrain, ‘Placare Domine’ (Subside your anger, Lord) powerful and

moving.

Stirring singing during double-choir storm chorus was complemented

elsewhere by the ensemble’s lovely, melodious blend and the text was

carefully enunciated, especially in the closing chorus of repentance which

follows the abrupt conversion of Ninevites - a fitting moral message for

the departing congregation at the Oratorio del Santissimo Crocifisso to

carry with them but perhaps, judging from the responses around me, not

quite such apt fulfilment of the expectations of those in Snape Maltings

Concert Hall.

I Will Not Speak. Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

I Will Not Speak. Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

In I Will Not Speak, Conway sought to explore the interweaving and

fusing of sensuality and spirituality, violence and virtue in the works of

Gesualdo - a man renowned for the brutal murder of his adulterous wife,

Maria D’Avalos. I’m not sure if one could say that the sequence was

‘staged’. Votive candles fluttered - a representation of the special

candelabrum with fifteen candles which were distinguished one by one as

each day’s service, commencing at nightfall, began, until only a single

Paschal Candle remained; and also a metaphor for the quivering, fervent

dialogue between faith and doubt. And, there was a slow ritual progress

amid the flickering tiers of orange light, as the shadows multiplied and

deepened until God plunged the world into darkness, the Crucifixion

extinguishing the light of the world.

In any case, I cannot see any reason for adding dramatic action or movement

to these works. There is enough melodrama within the madrigals,

dominated as they are by a love which burns with the heated passion of a

self-consuming destructive desire, and the Tenebrae Responses, which seek

to bring human darkness and despair into balance with the hope of

forgiveness and rebirth. Indeed, the music seems to express such

interiorised agonies and ecstasies that all such external events are

negated. Certainly, gestures such as a blowing of breath at the start of

John Donne’s ‘The Expiration’ seemed somewhat trite. And, it seems all too

perfunctory to make a direct link between Gesualdo’s tragic destiny and the

torments of his musical voice, such as was intimated by the recitation of

episodes of the composer’s life amid extracts from the Psalms,

Igantius Loyala’s Spiritual Exercises, and The Spiritual Canticle of St John of the Cross.

Perhaps the chromatic distortions and intensities find their complement in

the bitter, often self-lacerating arguments of the metaphysical texts of

John Donne and George Herbert, but the conflicts expressed therein are

those of a single voice, and the division of the poetic lines between

different voices weakened this interior drama. The singers again performed

assuredly, accompanied predominantly by strings, but the sweetness of the

blended timbre denied the astringent dissonances their full power.

Nicholas Mogg (Aeneas). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Nicholas Mogg (Aeneas). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Seb Harcombe’s Dido and Aeneas promised to restore the

musico-dramatic equilibrium. Designer Adam Wiltshire presented us with the

crumbling ruins of a Tudor manor - a metaphor for ravaged Carthage,

perhaps. But, even here there was ambivalence. Harcombe professed to have

viewed the opera ‘from inside the heroine’s mind’ - I guess that explains

why this Dido was staring into a hand-mirror at the start, and resumed this

position before the tilting fire-place/portico at the close - and there was

a disconcerting disjuncture between the realism of the Elizabethan

costumes, all stiffly starched ruffs and cod-pieces, and the

pseudo-psychodrama of much of the Gothic gestures and lighting.

There were a few doubtful moments: I’m not sure that witnessing Aeneas’s

rather rough wooing and writhing with his new amour to the accompaniment of

the theorbo’s elaborate, but not very erotic, ground bass repetitions, was

a substitute for the imagined mysteries of The Cave. But, despite this the

truly fine singing won the day. Susanna Fairburn’s terrifically vivid

Belinda was a good counterfoil for Sky Ingram’s depressive Queen: the

latter’s dull tunic and tortured visage brought to mind the heroines of the

Brontës, and the rich timbre of Ingram’s lower range was evocative of the

profound passions and neuroses of Jane Eyre and Cathy Earnshaw. Nicholas

Mogg’s Aeneas was an oddly indifferent courtier and courter, egoism rather

than empathy taking precedence as he entered with the flourish of a Walter

Raleigh or the Earl of Essex, presenting the Queen with a model ship which

honoured his own adventuring and achievements. Long, lank black locks made

the sonorous announcement of Frederick Long’s Sorceress even more

surprising and chilling than usual.

Sky Ingram (Dido). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Sky Ingram (Dido). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

The small forces necessitated some compromises and excisions. The doubling

up of Dido’s court and the coven of witches might have been thought to

support Harcombe’s hypothesis that the events were conjured by Dido’s

damaged psyche. But, the need for Dido to join the chorus, after Belinda’s

‘So fair the game, so rich the sport’, to help full out the sound, was less

convincing. Moreover, the score’s joyful moments and carefree pastoralism

seemed diluted.

During the final chorus, Dido rose and wandered, lost and unheeded through

the ‘mourners’: perhaps the latter had already forgotten their Queen’s

admonishment to ‘remember’? I’m not sure that this triple bill, beautifully

sung but of dubious rationale and relevance - an encore, surely not

necessary or appropriate after this most ‘perfect’ of operas, from

Carissimi’s Jephtha seemed to return us to the staticism of

earlier in the evening - will be one of my most vivid ETO memories.

But, Radamisto the night before had provided splendid enjoyment

and fulfilment. And, I look forward to ETO’s spring tour, which presents

three operas - Mozart’s Idomeneo, Rossini’s Elisabeth I,

and Verdi’s Macbeth - in which still more Kings and Queens in

battle for love, loyalty and power.

In the meantime,

ETO’s autumn tour

continues until 28th November.

Claire Seymour

Handel:

Radamisto

English Touring Opera: Radamisto - William Towers, Zenobia - Katie Bray,

Polissena - Ellie Laugharne, Tiridate - Doyle Grant, Tigrane - John-Colyn

Gyeantey, Farasmane - Andrew Slater; Director - James Conway, Conductor -

Peter Whelan, Designer - Adam Wiltshire, Lighting designer - Rory Beaton,

The Old Street Band.

Snape Maltings Concert Hall, Snape, Suffolk; Friday 2nd November

2018.

Purcell: Dido and Aeneas; Carissimi - Jonas; Gesualdo:

I Will Not Speak

Dido - Sky Ingram, Aeneas - Nicholas Mogg Belinda - Susanna Fairbairn,

Sorceress - Frederick Long, Spirit - Benjamin Williamson, Second Woman -

Alison Manifold, Sailor - Richard Dowling, Jonas -Jorge Navarro-Colorado;

Director (Dido) Seb Harcombe, Director (Jonas) Bernadette Iglich, Director

(I Will Not Speak) James Conway, Conductor - Jonathan Peter Kenny, Designer

- Adam Wiltshire, Lighting Designer - Rory Beaton, The Old Street Band.

Snape Maltings Concert Hall, Snape, Suffolk; Saturday 3rd October 2018.