When Mew died in 1928, the obituary in the local newspaper was painfully

terse: ‘Miss Charlotte Mary New [sic], ... a writer of verse.’ Today, while

Mew’s poetry is admired by a small but ardent group of devotees, her name

remains largely unfamiliar, although a forthcoming biography of Mew by

Julia Copus, to be published by Faber, will bring the poet’s life and work into the

public eye.

It was a life of tragedy and torment, illness and incarceration. Mew’s aunt

and uncle, on her mother’s side, both suffered from insanity and were

institutionalised. Of the seven children of Frederick Mew, a struggling

architect, and Anna Kendall Mew, only four survived childhood. When she was

nineteen, Charlotte’s eldest brother, Henry, afflicted by what would now be

diagnosed as schizophrenia was sent to a mental institution, where he spent

the last thirteen years of his life. Charlotte’s younger sister, Freda,

then in her early teens, was similarly plagued. Financial hardship followed

Frederick’s death in 1898 and Charlotte, her sister Anne, and their mother

moved into a rented home, subletting the upper floor and eking out a frugal

existence. Her mother died in 1923, and when Anne succumbed to cancer four

years later Charlotte began to suffer from delusions. When, in February

1928, she was diagnosed as neurasthenic, she voluntarily entered a nursing

home, where on 24 March she committed suicide by drinking Lysol.

[1]

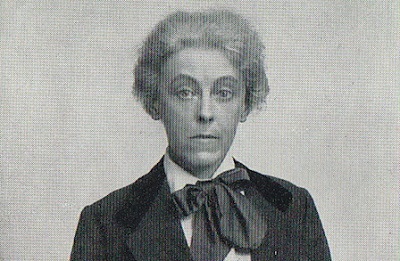

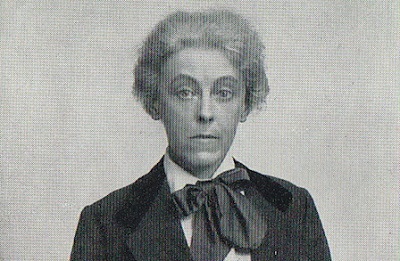

Diminutive, prone to wearing dull men’s suits, swearing and smoking with

equal vigour, Mew must have cut an odd figure even among the poets who

gathered at Monro’s Poetry Bookshop. Mew apparently told her friend Alida

Monro that she and her sister had determined early in life ‘that they would

never marry for fear of passing on the mental taint that was in their

heredity’ - perhaps influenced by the prevailing new theories in eugenics.

Her lesbianism only intensified her feelings of isolation and alienation.

Charlotte Mew.

Charlotte Mew.

However, beneath her reserved and reclusive manner, passion burned

fiercely. Though reluctant to recite her poetry at public readings, when

she did accept an invitation Mew startled the audience: ‘They sat facing

the little collared and jacketed figure, with her typescripts and

cigarettes … Once she got started (everyone agreed) Charlotte seemed

possessed, and seemed not so much to be acting or reciting as a medium’s

body taken over by a distinct personality. She made slight gestures and

used strange intonations at times, tones that were not in her usual

speaking range.’

[2]

Mew’s poetic voice is soon to be heard again, in a new expressive form.

Composer Kate Whitley has set six of Mew’s poems for soprano, bass and

strings, and these songs will be presented as part of a special concert at

Temple Church, London on Tuesday 30 April

. The programme has been curated by bass Matthew Rose, and brings together

soprano Katherine Broderick, pianist Anna Tilbrook and violinist Jan

Schmolck to celebrate music for voice commissioned by the Michael Cuddigan

Trust. Also on the programme is the world premiere of a new work by David

Bruce, plus Martin Suckling’s Songs from a Bright September, works

which were similarly commissioned by the Michael Cuddigan Trust, of which

Rose himself is a trustee. Rose comments, “Michael Cuddigan, along with his

wife Anne, were so kind to look after me as a student in Aldeburgh for many

years. Michael had the most amazing love for music and musicians, and we

started this Trust five years ago in his memory. I’m greatly looking

forward to this exciting evening of new works performed by some of the

country’s leading musicians.”

Matthew Rose. Photo credit: Lena Kern.

Matthew Rose. Photo credit: Lena Kern.

Kate is a composer-pianist and co-founder of The Multi-Storey Orchestra,

which, from its base at Bold Tendencies car park in Peckham, takes

professional performances to local schools and further afield. She has

frequently striven to take classical music into new contexts and before new

audiences. Her concert piece, Sky Dances, was performed at

Trafalgar Square as part of a programme that brought together the LSO, the

Guildhall School of Music and Drama, and 70 young musicians from East

London. Paws and Padlocks, a children’s opera about two children

who get trapped overnight in a zoo, was performed at Blackheath Halls in

2016, while Speak Out, which set words by Malala

Yousafzai, was performed by BBC National Orchestral and Chorus of Wales on

International Women’s Day 2017 in support of the campaign for better

education for girls. NMC Recordings released a CD of her music,

I am I say

, in 2017.

I ask Kate what it was that had drawn her to Mew’s poetry. She explains

that the initial impetus came from Sir Stephen Oliver, a Trustee of the

Michael Cuddigan Trust and the great-nephew of Mew’s life-long friend Ethel

Oliver, who got in touch with Kate and, giving her copy of Mew’s collected

works, suggested that she might compose some settings. Kate had never heard

of Mew but found the poems instantly appealing and absorbing; she discussed

Mew’s work with Julia Copus, whose knowledge and love of the poems were of

enormous value as she guided Kate’s selection of three poems, her choice

being influenced by length and theme. ‘The Farmer’s Bride’ was framed by

two shorter poems, ‘Rooms’ and ‘Sea Love’, and these

three songs

were performed by Matthew Rose and the Albion Quartet in Orford Church in

June 2017. Kate has now composed three further settings - ‘I So Like

Spring’, ‘Absence’ and ‘Moorland Night’ - which will be sung by Katherine

Broderick on 30 April.

Mew strips bare the inner lives of her poet-speakers, with often painful

honesty. There is a driving tension between restraint and release - as if

Mew wants both to speak out and hold back. Images of confinement allude to

the social structures which force women into emotional, physical and

financial dependency on men. But, for all her personal idiosyncrasies, Mew

was no ‘New Woman’, and remained a Victorian in her social outlook,

lamenting the loss of old certainties as the world moved forward into the

age of modernity, of uncertainty and crisis. I wonder whether Kate finds,

as I sometimes do, the wrought emotional intensity of Mew’s poems somewhat

overwhelming? On the contrary, Kate tells me, that it was this very

intensity, conflict and rawness which she found so moving.

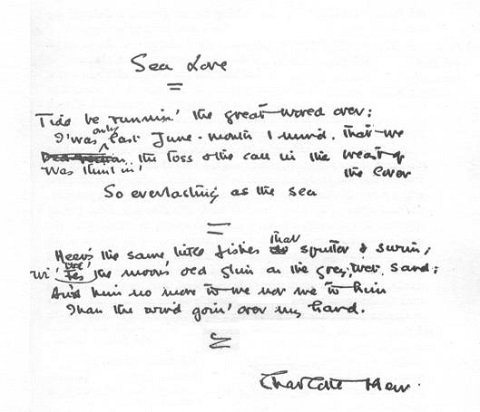

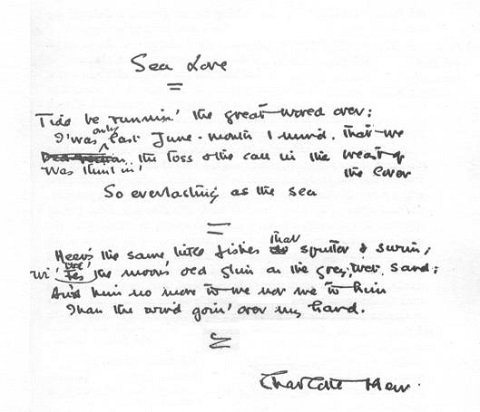

Alida Monro reproduced this corrected manuscript of Sea Love in the 1953 Collected Poems. The manuscript is now in the Buffalo Collection.

Alida Monro reproduced this corrected manuscript of Sea Love in the 1953 Collected Poems. The manuscript is now in the Buffalo Collection.

She was, though, initially a little daunted to be confronted with texts so

different from anything else she had previously set to music. The rhyming

couplets of ‘The Farmer’s Bride’ and the regularity of the form of ‘Sea

Love’ seemed to demand regular phrase shapes, an approach to text-setting

which was contrary to Kate’s usual, instinctive practice. But, in the

event, the way the poetic form imposed itself upon the musical form was a

positive stimulus, for it seemed to offer a way of capture the tenor of

Mew’s world and our distance from the historical past: “It felt natural to

compose in this way; it was the best way to communicate what the poem

says.”

‘The Farmer’s Bride’ is a man’s account of his marriage to a woman who

rejects his attentions and demands. One night she escapes but is hunted

down by her husband and other villagers who find her among a flock of

sheep. The crowd ‘caught her, fetched her home at last/ And turned the key

upon her, fast’. She submits to the conventions of domesticity, ‘So long as

men-folk keep away’, and each night climbs a stairway: ‘sleeps up in the

attic there/ Alone, poor maid’. I wonder if Kate hears the speakers in

Mew’s poems as being male or female? The speakers in Kate’s second set of

poems could be either, she says, but it’s a male voice we hear in ‘The

Farmer’s Bride’. We never actually hear the voice of the young girl after

whom the poem is named, and this is the point - she is described from the

male point-of-view, a ‘madwoman in the attic’:

Three summers since I chose a maid,

Too young maybe—but more’s to do

At harvest-time than bide and woo.

When us was wed she turned afraid

Of love and me and all things human;

Like the shut of a winter’s day

Her smile went out, and ’twadn’t a woman—

More like a little frightened fay.

I agree with Kate that here Mew assumes a male voice in order to

communicate strong erotic desire: the man’s lament is not for his young

bride’s sadness and suffering, but for his own unfulfilled desire.

Katherine Broderick.

Katherine Broderick.

The image of the locked room or enclosed space recurs repeatedly in Mew’s

poems, exposing her loneliness, and we find it elsewhere in Kate’s

settings. ‘I remember rooms that have had their part/ In the steady slowing

down of the heart’ says the speaker in ‘Rooms’, noting that ‘The room is

shut where Mother died’. The word ‘shut’ reappears in ‘Absence’ - ‘In

sheltered beds, the heart of every rose/ Serenely sleeps to-night. As shut

as those/Your guarded heart;’ - and ‘Moorland Night’: ‘My eyes are shut

against the grass’.

These poems have a dramatic lyrical tone, but the rhythms are restless as

the forms frequently juxtapose extremely short and long lines which tug

against the underlying meter, and the rhyme schemes are complex. I wonder

whether these formal idiosyncrasies were disinclined to lend themselves to

musical setting? Again, Kate seems to have found such elements creatively

inspiring. She describes the way in which the voice and strings work

together, sometimes the voice leading and the strings accompanying,

elsewhere the strings coming to the fore between the lines or at the end of

stanzas, and this seems to me to imitate the restless conflicts and

tensions within the poems.

‘Moorland Night’ is the final poem in The Farmer’s Bride. Here,

Mew seems to find resolution in nature:

My face is against the grass - the moorland grass is wet -

My eyes are shut against the grass, against my lips there are the little

blades,

Over my head the curlews call, And now there is the night wind in my hair;

My heart is against the grass and the sweet earth, - it has gone still, at

last;

It does not want to beat any more,

And why should it beat?

This is the end of the journey.

The Thing is found.

In an essay, ‘The Poems of Emily Brontë’, which is printed in Mew’s Collected Poems & Prose, Mew described Brontë as ‘a

self-determined outlaw’, ‘a soul which scorns the world with masterful

persistence and disclaims all comradeship save that of the “strange

visitants”’. Brontë’s poetry is, she says, ‘dominated by a note of pure

passion … a passion untouched by mortality and unappropriated by sex, the

passion of angels, of spirits, redeemed or fallen, if such there be and

sorrow of an ever-unsatisfied desire, she looked out upon the world, which

the sad circumstances of her environment, together with the gloomy bias of

her nature, showed so dark, with a curious indifference and mistrust’.

These words might equally describe Mew and her own poetry.

Kate Whitley’s

Six Charlotte Mew Settings can be heard at

Temple Church on 30th April 2019.

Claire Seymour

[1]

See Charlotte Mew: Collected Poems and Prose, ed. Val

Warner (London: Carcanet Press/Virago Press, 1982).

[2]

Penelope Fitzgerald, Charlotte Mew and Her Friends

(London: Collins, 1984), 111.