This Berenice, which channels Georgian grotesque humour, spiked

with a light peppering of present-day allusions, is thus a welcome breath

of fresh air, borne aloft on the wings of uniformly superb dramatic singing

in this ROH/London Handel Festival co-production.

Handel’s opera did not, however, have auspicious beginnings when it was

first presented in a theatre on the very site of the current day Linbury

Theatre. Appearing during the composer’s ill-fated 1736-37 season, when

competitive rivalry with the ‘Senesino Opera’ was taking its toll on

Handel’s health and hopes, Berenice was the composer’s shortest

running production, closing after four performances with Handel reportedly

‘very much indispos’d’ with ‘a Paraletick Disorder, he having at present no

Use of his Right Hand’. Apart from a brief outing in Brunswick in 1743,

there have since been just a couple of enterprising student productions (at

Keele University in 1985, and at Cambridge in 1993) and two recordings:

Alan Curtis’s 2010 offering with Il Complesso Barocco, which

followed the Brewer Chamber Orchestra’s 2003 recording conducted by Rudolph

Palmer.

Setting the opera in Handel’s eighteenth century enables Thomas to present

both elegance and effrontery. The powdered periwigs suggest polite

graciousness, but the urbanity is tempered by a coarseness - epitomised by

rudely rouged cheeks and the way the boisterous, buckled shiny shoes ride

rough-shod over the central, dominating velvet banquette - which reminds us

that malodorous chamber pots rather than chivalrous manners were the order

of the day.

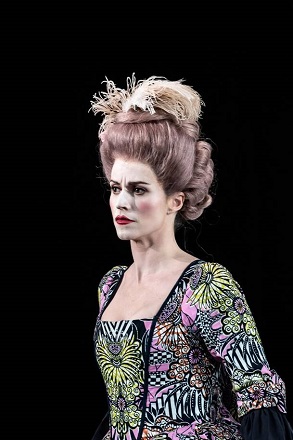

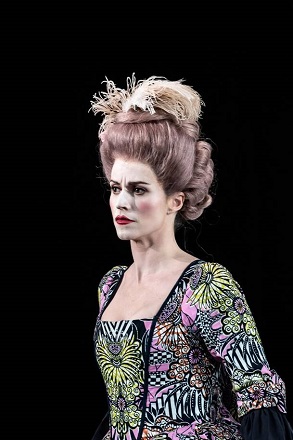

Rachel Lloyd (Selene). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Rachel Lloyd (Selene). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Thomas’s decision to transport the opera from Egypt 80BC to the backstage

of a Georgian theatre peopled by drama queens and fawning fops is a winning

one, suggestive of a political allegory of goings on at Handel’s Royal

Academy of Music, whose Covent Garden productions contended with those of

the rival Opera of the Nobility at the King’s Theatre. Moreover, Thomas

draws upon the tradition of Georgian tragedy which, often lightened by

comic contexts, frequently juxtaposed traditional and modern values within

strong female figures caught between husband and father, personal desire

and public duty: ‘the celebrity actresses playing these women exemplify new

individual freedoms as well as their intricate negotiations of a society’s

contradictory expectations.’

[1]

All well and good for the #MeToo age.

First, the single gripe. Selma Dimitrijevic has provided a new English

translation and judging from the few phrases readily audible - “politics is

cursed” - it’s a deft text. But, in the resonant Linbury acoustic,

consonants went AWOL and, in the absence of surtitles, great swathes of

recitative and aria text disappeared into the hinterland. Given the

unfamiliarity and complexity of the plot, this was not helpful.

Claire Booth (Berenice), Alessandro Fisher (Fabio), William Berger (Aristobolo), James Laing (Demetrio), Patrick Terry (Arsace), Rachael Lloyd (Selene). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Claire Booth (Berenice), Alessandro Fisher (Fabio), William Berger (Aristobolo), James Laing (Demetrio), Patrick Terry (Arsace), Rachael Lloyd (Selene). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Hannah Clark’s very open set design, for all its focal impact, perhaps does

not help. An emerald green, velvet, semi-circular sofa, adorned with a pink

fringe, is the sole piece of ‘set’, seeming to extend the seating of the

house itself as it stretches across the stage, set within an embracing

black expanse. It houses, during the overture, a motley crew of thespians

and toffs sipping Earl Grey and engaging in piquant exchanges, its peak

crested with a bloomy display worthy of a psychedelic Dutch flower

painting. There are a few reminders of the drama’s Egyptian roots - in the

brightly hued designs adorning the regal sisters’ pannier hoops, and the

two Barbary Lion gates guarding stage left and right.

The plot is a prototype cat’s cradle of romantic knots. Alessandro loves

the Egyptian Queen Berenice, who is betrothed to Demetrio Prince of

Macedonia - who loves the Queen’s sister Selene - but Berenice, a marital

pawn at the hands of the Roman Emperor, is forced into betrothal to Arsace.

Baroque amatory quadrangles are here expanded to become a pentagon of

possible romantic connections between the Egyptian queen, her sister, and

three potential husbands, at the heart of which two feisty and resentful

sisters rage, riot and rule.

James Laing (Demetrio), Patrick Terry (Arsace) and on-stage continuo. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

James Laing (Demetrio), Patrick Terry (Arsace) and on-stage continuo. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

With the continuo trio of Mark Caudle (cello), Oliver John Ruthve

(harpsichord) and Jonas Nordberg (archlute) bewigged and seated amid the

action - they have their music snatched from under their noses on occasion

- conductor Laurence Cummings was nestled in the Linbury pit with just

strings, oboes and bassoon. This was one of Handel’s low-budget

orchestrations but, in Cummings’ hands, no less vibrant and buoyant given

the scant resources. Tempi seemed just right, and the lean string textures

did promote the voices to the fore; that said, Cummings might have drawn

greater variety of articulation and tone from the London Handel Orchestra

string players.

What really made this such a terrific evening of musical drama, though, was

the commitment, engagement and prowess of the superb cast. As the titular

monarch, Claire Booth evinced regal righteousness and authority, and a

quirky unpredictability, singing with real bite: a little brittle perhaps

in her opening rejection of patriarchal command addressed to the Roman

ambassador, ‘No, che servire altrui’, though topped with some fantastically

acerbic cadential trills, but softened subsequently to convey the Queen’s

conflicting emotions. Berenice’s Act 3 ‘Chi t’intende?’ was a tour de force of musico-psychological probing aided by James

Eastaway’s delicious oboe obbligato.

Jacquelyn Stucker (Alessandro) and Patrick Terry (Arsace). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Jacquelyn Stucker (Alessandro) and Patrick Terry (Arsace). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Rachel Lloyd flounced furiously as the feisty Selene, dark of tone and

temperament, the fioritura fiery but pristine. As Demetrio, loved by both

sisters, James Laing sang with unforced strength, flexibility and

expressiveness. It was really satisfying, too, to see young members of the

cast finding their musico-dramatic feet: Patrick Terry’s Alsace was goofily

gormless - we felt for him at the close when he was a loose end as the

lovers’ tied the marital knots - though still calmly negotiating the

roulades of Alsace’s rage aria, while Alessandro Fisher displayed

confidence, professionalism and assurance as Fabio. William Berger was able

to summon vocal intensity as Aristobolo.

Best of all, though, was Jette Parker Young Artist Jacquelyn Stucker as

Alessandro. The role is less virtuosic than the others, but the pure

directness of Stucker’s lyrical spinto surely conveyed the integrity of a

man who puts love above self-advancement, and the elegance of the soprano’s

stylish phrasing was wonderfully engaging and honest.

The singers balanced a sure sense of Handelian style - and impeccable

tuning and passagework - with an individuality of expression which added

warmth to what might have been a rather chilly satire. In the concluding

ensemble, with the marriages of Alessandro to Berenice and Demetrio to

Selene resolving the political and amatory tensions, the soon-to-be-weds

sing of the joyous harmony that allows them to set aside the struggles of

love and politics. Heart-warming sentiments: if only things were that

‘simple’ in real life.

Claire Seymour

Handel: Berenice

Berenice - Claire Booth, Selene - Rachael Lloyd, Alessandro - Jacquelyn

Stucker, Demetrio - James Laing, Arsace - Patrick Terry, Fabio - Alessandro

Fisher, Aristobolo - William Berger; Director - Adele Thomas, Conductor -

Laurence Cummings, Designer - Hannah Clark, Adaptation - Selma

Dimitrijevic, Lighting design - D.M. Wood, Movement director - Emma Woods,

London Handel Orchestra.

Linbury Theatre, Royal Opera House, Covent Garden; Friday 29th

March 2019.

[1]

See The Oxford Handbook of the Georgian Theatre 1737-1832

edited by Julia Swindells and David Francis Taylor.