Though hard at work on his opera The Excursions of Mr. Broucek,

which was first performed in 1920, when he returned to Brno Janáček

immediately started sketching the first ten songs of what was to become a

22-song cycle for tenor, mezzo-soprano and piano, The Diary of One Who Disappeared. It set poems by Ozef Kalda that

had been published in the Brno newspaper, Lidové noviny,

on 14th and 21st May 1916, titled ‘From the pen of a

self-made man’. The poems told the tale of a young Czech boy, Janíček, from

‘a good family’, who is seduced by ‘a dark Gypsy’, Zefka, and lured into

the ‘free’ life of the traveller.

That Stösslová was the inspiration for The Diary is in no doubt:

the composer wrote to her from Brno, on 10th August 1917: ‘Will

you believe that I’ve not yet got out of the house? In the morning I potter

around in the garden; regularly in the afternoon a few motifs occur to me

for those beautiful little poems about that Gypsy love. Perhaps a nice

little musical romance will come out of it - and a tiny bit of the

Luhačovice mood would be in it.’ A year later, on 2nd September

1918, his mood was less optimistic: ‘It’s too bad my Gypsy girl can’t be

called something like Kamilka. That’s why I also don’t want to go on with

the piece. I can’t explain why you don’t write to me … I have nothing more

than memories - when then, so I live in them.’

Janáček continued work on The Diary during the following two

years, completing it in 1920. It was first heard at a private performance

that year, and then premiered at the Reduta Theatre in Brno on 18 th April 1921. There is undoubtedly an ‘operatic’ dimension about

the cycle, not least because, after the first eight songs in which the

tenor recalls when he saw Zefka, songs nine to eleven act out that first

meeting, as the composer turns indirect speech into direct interaction.

Zefka enters at the end of song eight, and an offstage female chorus (like

that which represents the soul of the Volga in Káťa Kabanová)

sings the narrative of a seduction Janáček deliberately avoids portraying

‘on stage’.

In song nine, Zefka sings: “Welcome Janíček, welcome here in the wood. What

happy coincidence brings you this way? What are you standing here like that

for? So pale; so still; Why, are you perhaps afraid of me?” To which the

young man replies, “I really have no cause to be afraid of anyone. I came

here only to cut an axle-pin”, whereupon Zefka invites him to put aside his

duties and to listen to her gypsy song. The remaining songs chart the

aftermath of the seduction.

Photo credit: Jan Versweyveld.

Photo credit: Jan Versweyveld.

Not surprisingly, there have been various dramatizations of The Diary - including Shadwell Opera’s

Grimeborn production

in 2017. Janáček himself is reported to have said that he wanted the cycle

to be performed in ghostly half-lighting. That said, the drama is present

in every note of the music. The Diary does not depend for its

power on overt context, gesture or symbol. That over-prescription might in

fact destroy the almost visceral intensity of the work was something that I

felt very strongly during this staging of Ivo van Hove’s ‘interventionist’

staging at the Royal Opera House’s Linbury Theatre. Superimposing an

autobiographical narrative on the tale told in poetry, and commissioning

additional music and songs from the Belgian composer Annelies Van Parys

which ‘allow us to see some of the story form Zefka’s perspective’, van

Hove almost doubles the work’s length while significantly diluting its

expressive immediacy.

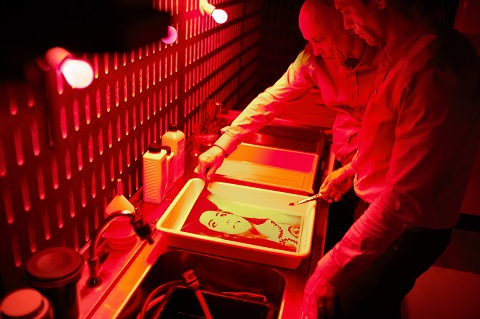

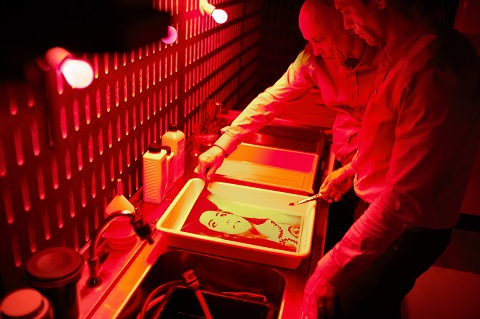

Van Hove worked with two of his regular collaborators for this 2017

production for the Belgian company Muziektheater Transparant: set and

lighting designer, Jan Versweyveld, and costume

designer An d’Huys. Versweyveld’s set seems to shift us forward from the

latter years of the First World War to the 1960s, and from nature to

‘civilisation’: specifically, to a photographic lab-cum-studio flat,

comprising kitchen, dark room, office and bedroom, the patterned lighting

effects intended, I assume, to evoke the landscape of the original woodland

tryst. The confined space can, however, accommodate a grand piano. Janíček

(tenor Ed Lyon) is now a photographer; rather than reliving his memories

through music, he projects his remembered encounter - the gypsy’s name, an

image of the Romany girl - onto the lab-apartment’s walls, assisted by an

elderly man (Wim van der Grijn) who, we learn, is the composer himself.

Photo credit: Jan Versweyveld.

Photo credit: Jan Versweyveld.

At the start, all is silent. A woman in red (Marie Hamard) enters and is

instructed by a recorded male voice to make a cup of tea, sit at the piano

and tap out a scale, some snatches of melody. It feels clunky and awkward.

Pianist Lada Valesova then takes her place at the keyboard; her playing is

the linchpin of the performance, every gesture redolent with a clear vision

of musical meaning and empathy for the composer’s emotive language. What a

pity the piano lid remains closed throughout, though this does not prevent

Valesova from conjuring emotional fire and frailty with equal insight and

impact.

Lyon’s singing is fervent and precise, though there’s a lack of Slavic

colour and passion, for all the rolling around on the carpet in which he

and Hamard indulge. But, Lyon also conjures a telling sincerity and

vulnerability which is countered by Hamard’s vocal strength. Van Parys’

music merges into Janáček’s songs with surprising persuasiveness, though I

can’t help but feel that Janáček’s decision to allow the gypsy’s voice to

be heard only in the central encounter strengthens the yearning and desire

communicated by Janíček.

Marie Hamard and Ed Lyon. Photo credit: Jan Versweyveld.

Marie Hamard and Ed Lyon. Photo credit: Jan Versweyveld.

There’s nothing amiss with the ‘quality’ of the individual performances.

But, the whole is strangely cold and clinical. One thing that is sadly

missing is the exoticism of the ‘gypsy’; a red ‘business dress’ and hooped

earrings don’t really compensate. Writing to Stösslova from Hukvaldy in

July 1924, the composer declared, ‘And Kát’a, you know, that was you beside

me. And that black Gypsy girl in my Diary of One Who Disappeared -

that was especially you even more.’ Later, in April 1927, a year before his

death Janáček wrote, ‘Wherever I am, I think to myself: you can’t want

anything else in life if you’ve got this dear, cheerful, black little

‘Gypsy girl’ of yours’.

At the time of The Diary’s composition, there was considerable

prejudice against the gypsy population in Moravia, and the cycle’s original

text had included political comments about the need for a gypsy homeland

(and indirect plea, perhaps, for a Czech homeland). Janáček scholar Michael

Beckerman’s observations are instructive: ‘For centuries the Gypsies, hated

and reviled, nonetheless furnished material for myriad erotic fantasies,

becoming the dark tabula rasa on which all the base and sensual

fantasies of white society were projected.’ In 1918 the new country of

Czechoslovakia was formed, guaranteeing equal rights to all citizens -

including 20,000 gypsies: ‘far from being a harsh, disturbing or sinister

presence, the Gypsies at this time functioned as what we might call

“orientalism from within”, an exotic symbol of freedom, passion and

improvisation.’ Van Hove almost completely ignores, or destroys, this -

surely fundamental - dimension of the work.

At the close of van Hove’s realisation, the seated figure of Wim van der

Grijn reads and then burns his letters to Stösslova, dropping the flaming

pages into a waste-paper bin. His unfulfilled dreams now ashes, he climbs

into the small bed, presumably ready for death. But, The Diary

ends in defiance and hope, not despair. Originally the vocal climax came in

song 14, the height of Janíček’s desolation and hopelessness, “Oh what have

I lost!” But, Janáček’s revisions shifted the emotional peak to the final

song, which rises to a top C: “All that is left is for me to say goodbye

forever.” And, with a farewell to his father, mother and little sister,

“the apple of my eye”, Janíček departs: “Zefka is waiting for me with our

son in her arms!”

Van Hove’s staging is refined where it could be raw; elegant where it could

be elemental. He denies us intimacy, immediacy - an intensity, recalling

the string quartets, which draws us into the stories the composer tells,

whether fictional or autobiographical. And, he denies us the hope and

consolation that Janáček’s final song exudes.

Claire Seymour

The Diary of One Who Disappeared

: Leoš Janáček and Annelies Van Parys

Tenor - Ed Lyon, Zefka - Marie Hamard, Actor - Wim van der Grijn; Director

- Ivo van Hove, Set/lighting designer - Jan Versweyveld, Costume designer -

An d’Huys, Dramaturg - Krystian Lada.

Linbury Theatre, Royal Opera House, London; Wednesday 5th June

2019.