The fact that this production - and its set - is so interior-focused strips

away every notion of grandeur and epic scale in this Boris Godunov

. This can, in all fairness, be liberating. After all, the opera is set

during ‘The Time of Troubles’, a period during the reign of Tsar Boris of

austerity and starvation. One only has to look at the ragged ends of

Boris’s own imperial robe to notice he doesn’t seem immune to the

deprivation that affects those he rules over.

If Jones doesn’t much care about what Russia looks like outside the walls

of the set, he most obviously does care about the psychodrama of Boris Godunov. This is a portrait - and for the much of the opera

portraits are liberally hung to reflect this - into the deeper recesses of

a mind collapsing into madness. The more you watch Jones’s Boris,

the less it owes to Pushkin and more to Shakespearian tragedy. The repeated

throat-slashing of the murdered child heir, Dmitry, (cleverly masked -

kabuki-style - to add authenticity to the usurper’s claims), clearly

alludes to Richard III and his murder of the princes in the Tower. But this

Boris is King Lear with all the same problems and deficits: a

ruler over an unstable kingdom, obsessiveness over an heir, a tragic

relationship with a daughter, a mind descending into hallucination and

insanity. It shouldn’t go unnoticed, either, that Boris and the Holy Fool

provide a similar dramatic function to that of Lear and his Fool - even to

the extent that the nobility or wisdom of the latter, whether in the opera

or the play, is always greater than that of the ruler.

ROH’s Boris Godunov, Company. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

ROH’s Boris Godunov, Company. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

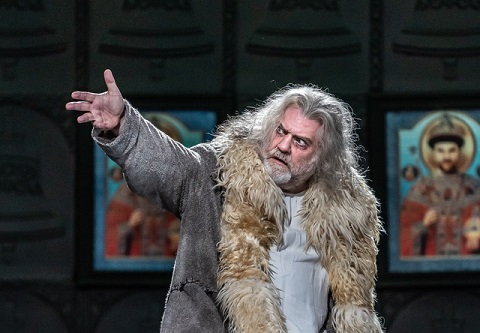

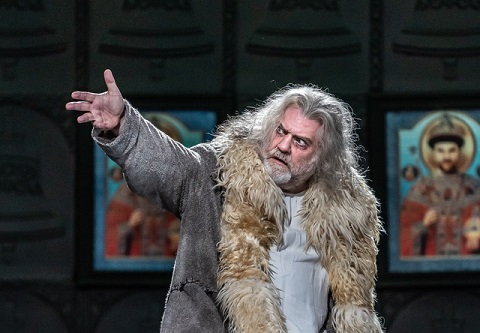

There is probably never any doubt as to Boris’s guilt, or complicity, in

murder in this production. Jones certainly has the most gifted actor-singer

of all in Bryn Terfel whose Boris has the most staggering stage presence.

Terfel’s eyes - and what he does with them is simply unmatched. For any

actor to command a stage with his eyes alone - as Terfel does - is quite

remarkable and it begins here even before the Coronation Scene. The gaze,

the stare, the madness, the sheer darkness was riveting. It’s worth the

price of a ticket alone just to see Terfel look at you - it’s in turn

terrifying, and completely compelling. Pimen’s ‘Chronicle of Russian

History’, which we see as a series of large portraits, clearly paints a

similar picture of Boris. The eyes glower, the face is unbearably ugly in

its tortured expressions - a sharp contrast to the angelic, deified Feodor

beside him. Even in the crowd scene outside the Kremlin Boris is simply

scripted as a ruler who is indifferent, or at best incapable of empathy.

Historically, these might not be entirely accurate depictions of Boris, but

Jones turns him in to someone - as Pimen suggests - as a Tsar worse than

Ivan.

Covent Garden have chosen to use Mussorgsky’s 1869 version (in the Michael

Rot revised edition) which has both advantages and drawbacks. There is

certainly greater fidelity to Pushkin’s text, and ending with Boris’s death

- especially, when in this performance, it was so powerful and so tragic -

seems more satisfactory. But it takes a better production than Richard

Jones’s to stem the impression we are watching a series of tableaux rather

than a single, immutable opera. It is obviously not Jones’s fault that

Mussorgsky writes for such large choral forces - but it is a problem when

those choruses struggle in such a compressed space. Mimi Jordan Sherin’s

lighting - a vast sheet of white light which stretches entirely across the

stage - flattens the height, whilst Miriam Beuther’s black set (even if it

does have a raised upper platform) stifles everything lower down. There is

something Romanov (later, rather than earlier) about Nicky Gillibrand’s

costumes; and the tattered rags of the hungry and dispossessed owe much to

David Lean’s vision of Dickens’s Oliver Twist.

Bryn Terfel (Boris Godunov). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Bryn Terfel (Boris Godunov). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

The 1869 version is also much more heavily cast for male soloists, perhaps

less operatic than the 1872 version, more recitative in style and a little

more kuchkist. I think there will always be those who question

whether Terfel has the power - or depth of sound - to sing the role of

Boris. One will always probably prefer the authenticity of a Russian bass

in this part, but what Terfel does bring to Boris is such insight and

tragedy to him. The acting is such an extension of what he does with his

voice you wonder what comes first. He is that very rare thing, the complete

singer-actor. It is certainly the case that he felt underpowered when he

sang beside Matthew Rose’s superlative Pimen in the final scene; on the

other hand, any one who heard Terfel’s simply stunning death scene will not

forget it for a very long time. Where he probably has an advantage over a

bass here is that the voice can do so much more at a higher register

without straining and his ability to scale down the voice was

heart-rending.

Matthew Rose (Pimen). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Matthew Rose (Pimen). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Terfel does madness very well. One is reminded in a Terfel performance of a

conductor like Karajan in Berg - everything is geared towards total

physical and mental exhaustion. Matthew Rose’s Pimen was no less

commanding, though less intense in characterisation. The vocal lines are

long and steady, his bass rich and deep - in a sense a deeply ‘monkish’

performance, perhaps the closest and most authentically Russian sung from

this largely British cast. John Tomlinson, reprising the role of Varlaam,

was hugely impressive, giving a most virile and spirited performance of the

drunken monk. David Butt Philip’s Grigory was a little understated as the

back-pack, knife-wielding usurper for my taste. The smaller roles - one of

the notable features of Boris Godunov is that it is dominated by

so few singers - were all finely sung, notably Roger Honeywell’s Prince

Shuisky and, a particular standout, Sam Furness’s tin-headed Holy Fool.

The chorus of the Royal Opera House had a rather busy night, though one

might argue Ben Wright, the movement director, had his work cut out by the

lack of space they had to move in. The singing was first rate, as was the

playing of the orchestra under the rather swift baton of Marc Albrecht.

This was a performance which ran for a more than comfortable two hours.

There is, I think, a good reason why Boris Godunov remains

difficult to stage well: it’s just written that way. Richard Jones doesn’t

really succeed in doing so, though if we want a study in the madness of

Tsar Boris, he has designed one for Bryn Terfel that succeeds on almost

every level. Terfel carries this production by his sheer presence alone. I

think the question is, would this production remotely work with any other

singer in the role? I suspect the answer is a resounding no.

Marc Bridle

Modest Mussorgsky: Boris Godunov

Bryn Terfel (Boris Godunov), Roger Honeywell (Prince Shuisky), Matthew Rose

(Pimen), David Butt Philip (Grigory), Boris Pinkhasovich (Schelkalov), John

Tomlinson (Varlaam), Harry Nicholl (Missail), Haegee Lee (Xenia), Anne

Marie Gibbons (Hostess of Inn), Sam Furness (Holy Fool), Jeremy White

(Nikitch), Adrian Clarke (Mityukha), Alan Ewing (Frontier Guard),

Christopher Lemming (Boyar); Richard Jones (Director), Marc Albrecht

(Conductor), Miriam Buether (Set designer), Nicky Gillibrand (Costume

designer), Mimi Jordan Sherin (Lighting designer), Ben Wright (Movement

designer), Chorus and Orchestra of the Royal Opera House.

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Wednesday 19th June

2019.