Few of these globetrotters come for Pesaro’s mediocre restaurants, beaches or tourist sites. Nor is the venue special. In contrast to Macerata’s romantic outdoor space, this gala took place in a bland auditorium constructed inside a suburban multi-purpose arena named after a local producer of commercial refrigerators.

Everyone came to hear great performances of works by Gioachino Rossini, whose birthplace Pesaro is. The last four decades have witnessed a revolution in Rossinian performance-practice, based largely on new critical editions of lesser-known works and fresh insights into vocal style. Many of these innovations were pioneered at the Rossini Festival. What better place to assess the state of the Rossinian art?

Singing Rossini is harder than it seems. His operas may seem on the surface to be naïve and uncomplicated. Yet underneath lies much craft, cunning, wit, depth – as well as formidable technical difficulty. To portray all this with effortless charm poses exceptional challenges and opportunities for singers – and universally loved experiences for audiences.

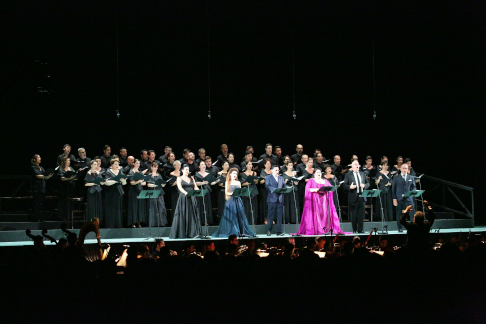

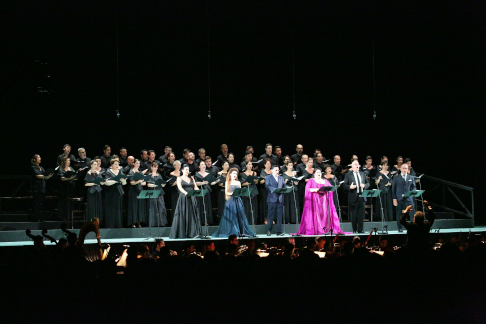

This gala contained excerpts from Rossini’s most famous operas. The first half drew on three madcap comedies (Il Barbiere di Siviglia, La Cenerentola, and L’Italiana in Algeri) for which he is best known. These works bring to life enduring stereotypes of Italian life dating back to commedia dell’arte: the foolish old man, the conniving servant, the blustering military officer, the honorable gentleman, the greedy man of means, and the romantic young lover. After intermission, the evening continued with selections from two serious operas (Ermione and his culminating work for the stage , Guillaume Tell), heroic works of genuine idealism that set the stage for the more overtly political and romantic operas of Giuseppe Verdi.

The program was promising. Yet throughout the evening in Pesaro, the spirit of Rossini remained surprisingly elusive.

The tone was set from the start, with the Sinfonia (overture) to the Barbiere of Seville. Unlike the famous overture to Guillaume Tell, given a slightly more satisfying performance in the second half, this is not a concert piece as much as a farcical buffo aria. Each of its sections – grand chords, a bucolic melody, a plaintive complaint, a raging storm, two long crescendos, and a dashing finale – come pell-mell on top of one another, with no real underlying logic. To capture this crackling spirit, the formal correctness of Rossini’s musical language must be balanced with a sense of zany improvisation.

The Orchestra Sinfonia della RAI played reasonably well and some woodwind solos and the precise articulation of the upper strings were superb. Yet veteran conductor Carlo Rizzi encouraged them to play like a symphony orchestra, not a pit band. Torpid and unvarying tempos (rests carefully counted out), an earnest emphasis on sonic beauty, and an even dynamic drained the piece of all its wit and sparkle.

Much of the evening proceeded in this way, also on the vocal side. Singer after singer seemed unable to capture Rossini’s vivid and witty musical-dramatic caricatures. Franco Vassalio offered astonishingly dull versions – cautiously read from the music – of Rossini’s two greatest baritone arias: “Largo al factotum” (Barbiere) and “Sois immobile” (Guillaume Tell). The first lacked personality, the second pathos .

Paolo Bordogna’s account of Barolo’s archaic rant, “A un Dottor della mia sorte,” lacked appropriate vocal resonance (is he a bass at all?) or any inkling of how perfectly Rossini captured for all time the absurd futility of an angry dad lecturing a rebellious teenage girl. Bordogna suffered by comparison to veteran Michele Pertusi, who contributed only to the ensembles yet demonstrated clearly how resonant a genuine Italian bass should sound.

Russian mezzo Anna Goryachova and her tenor compatriot Ruzil Gatin (?), a last minute replacement, sang solidly but unremarkably: she produced resonant low tones and he harsh high ones.

Even American tenor Lawrence Brownlee, a wonderful singer at his best, seemed to be a bit off his game. One has to admire his courage in leading off with “Cessa di più resistere” from Barbiere – an aria so long and demanding that most tenors refuse ever to perform it. Yet Brownlee’s voice was pinched throughout and the opening segment off-pitch. In the slow romantic middle section, he recovered, phrasing with poignant delicacy, yet the vocal acrobatics in the finale were no more than solid.

It fell to the three remaining singers to save the evening.

Superstar Rossinian tenor Juan Diego Flórez contributed one showpiece to each half of the program, the elegant “Sì, ritrovarla io guiro” from Cenerentola and the heroic “Asile héréditaire” from Tell. Flórez is an assured vocal superstar: his rock-solid technique, accurate intonation, clear diction and, above all, ringing high “money notes.” In recent years, moreover, Flórez has enhanced his ability to sing softly with real musicality.

Yet whereas the first aria deserved the ringing ovation it received, the second disappointed. Flórez’s voice, impressive though it is within its natural domain, just seems too light for a role in which the orchestral sound and vocal demands verge on those of middle-period Verdi. Flórez seemed uncharacteristically cowed: at times he failed to penetrate the orchestra, his dynamics and tempi varied little, his pleas for Swiss patriots to “Suivez-moi” seem unpersuasive, and he cut short the final (interpolated) high C.

More impressive was Angela Meade, a leading bel canto soprano from the US state of Washington who has recently moved on to Verdi. With maturity, Meade’s voice has gained astonishing size and weight: in the inspirational final ensemble from Tell, her rich tone penetrated effortlessly to the back wall of the auditorium through five soloists, an orchestra and chorus, all at fortissimo. She sang each word and shaped each phrase (recitatives as much as arias and ensembles) with unabashed passion and musical-dramatic intelligence. Her scena from Ermione was marred only by a tendency to flat high notes.

Yet the highlight of the evening came at an unexpected moment midway through the first half. Sicilian baritone Nicola Alaimo, a Pesaro regular, strolled on stage and effortlessly performed the aria that opens Act II of Cenerentola. It is Rossini at his most wittily and cynically Italian: striving Don Magnifico dreams of marrying his daughter to an important man so he can live a life of cozy corruption, surrounded by supplicants who offer money (and more) in exchange for political favors.

For five minutes, Alaimo inhabited the scheming father with no inhibitions. I have heard versions with more accurate buffo patter and with high notes, but it did not matter. His gestures, almost conversational phrasing, and superb vocal acting captured the Rossinian spirit. Even a friend beside me who had never heard the aria and (given the lack of supertitles) did not comprehend a word, immediately felt the fleeting magic of the moment.

Overall, however, the 40th anniversary gala was uneven, giving as much cause for concern as celebration about the future of Rossini singing.

Andrew Moravcsik