In Vincenzo Grimani’s libretto for Handel’s Agrippina, this

inveterate liar, intriguer and practiced murderess has a single aim - the

usurpation of her husband Claudius’s throne by her son, Nerone. The

Venetian Grimani, a nobleman and cardinal, knew a thing or two about

reaching the top, whether via diplomacy or duplicity: his career culminated

in his appointment as Viceroy of Naples in 1708. Not long afterwards, in

December 1709, his vicious satire depicting ruthless intrigues in ancient

Rome motivated by vengeance and sexual gratification was enticing the

punters at the Teatro Grimani di S. Giovanni Grisostomo in Venice. Agrippina ran for 27 performances, until February 1710: it was the

25-year-old composer’s first operatic triumph.

Some of Grimani’s cast of licentious liars had featured in Monteverdi’s L’Incoronazione di Poppea, 70 years earlier, in a more subtly

comic dramatic context. Barrie Kosky’s production of Handel’s opera - seen

first

in Munich

earlier this summer - ignores the fact that the Handel-Grimani take on

these power-sex conspiracies might be rather more than ‘just comic’, and

strives to turn proceedings into a Roman sit-com, with pairs of loathsome

criss-crossing lovers and colluding connivers coming a cropper. There is,

as always, both irony and pathos in Handel’s score, but Kosky puts his

money on frenetic farce.

Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Rebecca Ringst’s steel box-frame design offers plentiful stairways,

corridors, blinds and inner chambers for eavesdroppers to find hideaways

and intriguers to conspire. As the plottings unfold, the box swivels and

dismantles, its moving parts emblematic of the human chess game being

played by Agrippina. It’s no surprise that at the height of the

hugger-muggering - when, at the opening of act 3, a trio of Romans visit

Poppea’s apartments, lured by her panto-esque ploy of hide-and-hear -

Joachim Klein’s eye-burning lighting of the white-on-white interior renders

the audience as blind as the protagonists. Nor, that the Meccano-parts are

reassembled when Agrippina checkmates one and all.

Grimani’s libretto is one of the most psychologically and dramatically

convincing that Handel set, and even though Agrippina has a high

proportion of self-borrowed material (some scholars have suggested that as

many as 50 of the 55 separate numbers have known precursors), Handel’s

score is compelling, inspired by youthful creativity, confidence and

vigour. The recitatives are lengthy but persuasive, often bringing voices

together in ways which drive the drama onwards. In the ROH pit, conductor

Maxim Emelyanychev pushed the pace and challenged the singers to keep up:

the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment were impelled by the innate

harmonic energy and a driving and robust bass line. The continuo timbres

were varied and alert, and the oboe players deserved a bonus.

Iestyn Davies as Ottone. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Iestyn Davies as Ottone. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

So why, given too that there was some splendid singing to enjoy, did I feel

slightly dissatisfied? I think it’s because Kosky seems not to appreciate

Handelian irony. Grimani provides copious intrigue and irony. Handel

enhances this by composing music which is often at odds with the apparent

sentiments of the text. So, when in Act 1 the words of Agrippina’s ‘Non ho

cor che per amarti’ seem to assure Poppea that Agrippina is her BFF, the

minor key and sinuous melodic lines tell us otherwise. There is no need for

theatrical signposting. Time and again I found myself reflecting on a

Shakespearian parallel: that if Iago does not indeed seem ‘honest’ to the

other characters, then the dramatic credibility is destroyed - whatever

audience collusion is generated by Iago’s play-dominating soliloquies. In

Kosky’s production there is far too much minxing, mincing and

melodramatising. He doesn’t trust Handel to do the work for him.

Fortunately, Kosky has a fine cast to present his petulant playground

antics. Ever a theatrical animal, Joyce DiDonato relishes the extroversion

and exaggeration of Kosky’s conception of Agrippina, which seems to owe

much to American 1980s TV dramas Dynasty and Dallas.

DiDonato pushes her voice hard in Act 1, but doesn’t really delve into the

emotional depths of Act 2’s ‘Pensieri, voi mi tormentate’. With the

follow-spot shining, she wields a diamante-studded microphone with aplomb -

when Agrippina morphs into a Judy Garland clone (why?) - but it’s not until

the closing moments, when she claims that it was love for Claudio that led

her to secure the throne for Nerone, that the musical simplicity and

sincerity of ‘Se vuoi pace’ allows DiDonato - without Kosky’s interference

- to fulfil Handel’s deliciously ironic directness.

As Poppea, Lucy Crowe flounces and flirts hyperactively. If she’s not

‘doing a Marilyn Monroe’ on the steel staircase, then she’s fluttering her

skirts and flashing her knickers - this Poppea’s self-love outweighs her

suitors’ adoration! Not that Crowe doesn’t produce the vocal goods to

justify such adulation: Emelyanychev pushed her rather too fast in ‘Se

giunge un dispetto’ and after some dizzying coloratura the climatic

phrase-peaks rather lost touch with their harmonic roots, but Crowe

demonstrated fine breath control and rhythmic clarity.

Gianluca Buratto as Claudio, Lucy Crowe as Poppea. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Gianluca Buratto as Claudio, Lucy Crowe as Poppea. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

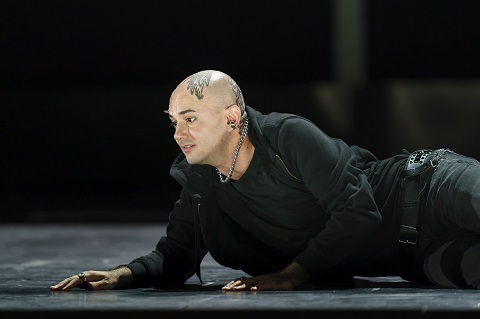

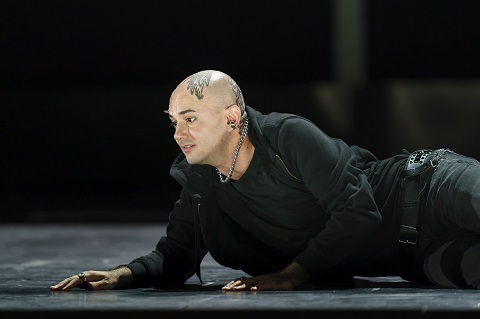

The first-night audience went wild for Franco Fagioli’s tattoo-headed,

eyebrow-studded, hoodie-slouching Nerone. I was less enamoured. Handel

wrote the roles of Nerone and the courtier Narciso for castrates; Fagioli

sings with a nerve-twitchingly wide vibrato and his tone is piercing rather

than ingratiating; he gets around the coloratura but in a rather

mechanical, rather than meaningful, way. I don’t think that this role needs

to be sung by a woman: one can imagine a rich feminine voice, such as that

of Philippe Jaroussky, serving the role well, and offering rather more

complex characterisation than Fagioli’s pouting, wall-pounding,

floor-stamping adolescent. Nerone’s final aria, ‘Come nube che fugge dal

vento’, in which he claims that he has broken the enchantment of his

infatuation for Poppea, did however suggest that Fagioli might have had

more to say than Kosky allowed.

Franco Fagioli as Nerone. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Franco Fagioli as Nerone. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Gianluca Burrato was dramatically convincing as Claudio, prepared to look a

fool with his trousers round his ankles, but his lower register was not

entirely secure or firm. As Agrippina’s would-be suitors Pallante and

Narciso, Andrea Mastroni and Eric Jurenas’s comic antics didn’t make much

of a mark, though there was little to fault with their singing; the same

could be said for José Coca Loza’s Lesbo, Claudio’s ‘Leporello’.

Iestyn Davies as Ottone was alone in his appreciation of the sincere

characterisation embodied in Handel’s music and text-setting. When he

appeared before the Imperial palace, expectant of glory in acknowledgement

of his heroic deeds, this Ottone seemed genuinely unaware that he

is about to be denounced as a traitor. Having been assaulted violently with

a lead pipe, he delivered the dissonant recitative and expressively

eloquent ‘Voi, che udite’ with a musical precision and psychological

perspicacity which was unique during this evening’s performance.

It was only at the very close of the opera that Kosky approached anything

like this sort of veracity. The director eschews Juno’s divine intervention

and offers instead a slow oboe-led movement from L'Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato. Agrippina retreats to the

steel-box and takes a seat, alone … victorious? Nero is Emperor: she’s won,

hasn’t she? Tantalisingly, in these final moments Kosky shows that he

understands the inherent tragedy that Handel ironically unfolds … the

moment is a bit too late to really make its mark, but it’s welcome. As

today’s politicians are realising, as events unfold, the winner doesn’t

necessarily take all.

Claire Seymour

Agrippina - Joyce DiDonato, Nerone - Franco Fagioli, Poppea - Lucy Crowe,

Ottone - Iestyn Davies, Claudio - Gianluca Buratto, Pallante - Andrea

Mastroni, Narciso - Eric Jurenas, Lesbo - José Coca Loza; Director - Barrie

Kosky, Conductor - Maxim Emelyanychev, Set designer - Rebecca Ringst,

Costume designer - Klaus Bruns, Lighting designer - Joachim Klein,

Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment.

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Monday 23rd September

2019.