08 Oct 2019

ETO's The Silver Lake at the Hackney Empire

‘If the present is already lost, then I want to save the future.’

‘If the present is already lost, then I want to save the future.’

Given the social and ideological context of our own present, the words of the German dramatist Georg Kaiser, written at the end of World War 1, might serve as both a dispiriting reminder and uplifting inspiration.

Certainly, it’s not difficult to see why English Touring Opera’s Artistic Director, James Conway, thought that Kaiser’s third and final collaboration with Kurt Weill, Der Silbersee (The Silver Lake), would resonate with audiences when the company take it on tour around the UK, alongside another that other sui generis ‘singspiel’, Mozart’s The Seraglio .

For while Der Silbersee is both informed by and a critique of its immediate context, it combines contemporary political allegory on the condition of Germany in the dying days of the Weimar Republic - it was premiered on 18th February 1933, less than a month after Hitler had become Chancellor of Germany - with utopian symbolism that enables it to transcend that context. Der Silbersee thus both addresses the condition of a historical present and articulates Kaiser’s ambition of saving the future, through social solidarity and reparation for injustice; and, the power and relevance of its promise of a better world will surely never cease.

That said, the contemporary reception of Der Silbersee suggests that its utopianism can’t easily be ‘disassociated’ from its specific historical moment. Following the Magdeburg premiere there were complaints from community organisations about ‘the degradation of art to the one-sided, un-German propaganda of Bolshevist theories … This play preaches the idea of class hate and contains innumerable open and veiled invitations to violence,’ while the Nazi newspaper Leipziger Tageszeitung sneered: ‘Kaiser, though not himself a Jew, belongs to the circle of Berlin literary Hebrews. His latest clumsy piece of staged junk is called Der Silbersee and has ‘music’ by Weill.’

Later, the writer Hans Rothe recalled the Leipzig premiere: ‘Everyone who counted in the German Theater met together for the last time. And everyone knew this. The atmosphere there can hardly be described. It was the last day of the greatest decade of German culture in the twentieth century. The Nazis’ barracking and yelling were somewhat disturbing.’ Indeed, the simultaneous productions in Leipzig, Erfurt, and Magdeburg were suspended, Weill departed shortly afterwards for the US, and there were no public performances of Weill’s music until the war had ended.

The challenge that Conway must rise to, then, is to respect Der Silbersee’s explicit refutation of the prevailing political trend of its time, while also communicating the ongoing relevance of its promise and embodiment of social transformation. We must understand the explicit darkness which Der Silbersee satirises and challenges, and also connect such shadows with those that darken our own disturbing days. It’s no easy task, and Conway is, I feel, only partially successful - but that’s in no way to diminish the dynamism and conviction of his production.

The work’s full title is Der Silbersee: Ein Wintermärchen , ‘a winter’s fairytale’ alluding both to Shakespeare and, significantly for its German audience, to Heinrich Heine’s 1844 satirical poem. Deutschland: Ein Wintermarchen. And, the action truly takes place in a ‘winter of discontent’: Kaiser’s libretto is peopled by the hungry dispossessed and rapacious capitalists whose policy of over-supply keeps prices high. Food banks and Lehman Brothers, anyone?

ETO Ensemble.

ETO Ensemble.

The action begins with Severin and his unemployed, starving comrades symbolically assuaging their hunger by burying a life-size doll. When they raid a grocery store, Severin is shot by Olim, a policeman, who, discovering that his victim has stolen only a pineapple - a token of aspiration rather the sustenance he needs - feels remorse and determines to make recompense by falsifying his report and resigning from duty. When he wins the Lottery, Olim buys a castle (a symbol of the Weimar state), installs Frau von Luber (a representative of the old Wilhelmine order) as housekeeper and devotes himself to serving as Severin’s anonymous benefactor. The latter, confined to a wheelchair, rages with vengeance towards his assailant. The intrigued Frau von Luber engages her penniless, guileless niece Fennimore to spy on Olim and Severin, and discovering Olim’s secret she blackmails him into signing away control of his property to her. Olim and Severin are expelled from the republic, in a winter snowstorm, and head towards the silver lake where they risk drowning in suicidal despair. However, Fennimore, who has brought about a reconciliation between the two men, explains that ‘whoever must continue will be carried by the Silver Lake’. Though it is spring, the lake has frozen over, and Olim and Severin are able to escape to a new world.

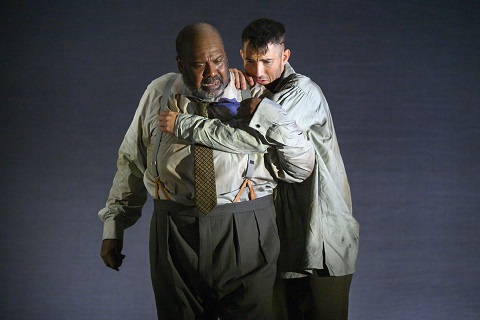

Ronald Samm (Olim); David Webb (Severin).

Ronald Samm (Olim); David Webb (Severin).

One of the challenges is how to deal with Kaiser’s lengthy text. When Der Silbersee was performed at the Wexford Opera Festival in 2007, director Keith Warner used Rory Bremner’s English translation of the complete text, but several critics found the ratio of spoken words and song unbalanced and in favour of the former. Except for the choral items which are sung in English, Conway and conductor James Holmes retain the original German for the sung numbers - a sensible decision as it foregrounds the historical particular - and have written a new, abbreviated English text for the narration, which is spoken by Bernadette Iglich. However, Conway throws the emphasis back on the ‘play’ at the expense of the ‘song’, by rejecting conventional surtitles in favour of Brechtian placards and banners, scrolls and even tickertape, upon which translations of the lyrics are stamped and scribbled. The problem is that as our eyes cast around Adam Wiltshire’s folding-scaffold set, searching in the gloom for the next cue, where the words are becomes more of a preoccupation than what they are saying.

This is particularly detrimental to the impact of the Chorus, whose interjections - as Brecht would have intended - are designed to both influence and articulate our own views: as when, for example, the Chorus persuade Olim to resist the allure of the Lottery Agent’s promise of compound interest in favour of altruistic investment in the common good. However, as Shop-girls, Grave-diggers and disaffected Youths, the Ensemble and Streetwise Opera make a strong-voiced chorus and deliver Bernadette Iglich’s choreography with vitality, complemented by Holmes’ slick direction of the instrumentalists, though the latter’s tone might have had a little more grit and grain.

ETO Ensemble.

ETO Ensemble.

Kaiser’s drama is driven by the transformation of the characters’ motivations, but it might be argued that in defining his protagonists the librettist relies less on psychological realism than on the emblematic depiction of social developments. Indeed, the Austrian director and actor Heinrich Schnitzler complained that Kaiser’s characters ‘often suddenly cease to be characters and only speak with Georg Kaiser’s mouth and brain about abstract philosophical and sociological matters’.

The ETO cast do, however, succeed in communicating credible feelings and motives. David Webb made Severin’s anger palpable and his singing was taut, while Ronald Samm’s Olim was appropriately reflective, his baritone languid at times but always gracefully solemn. Clarissa Meek avoided the temptation to turn Frau von Luber into a pantomime wicked witch; James Kryshak was a slick Lottery Agent and, as Baron Laur, joined the castle-commanding Frau in a deliciously wry duet celebrating the restoration of the old order - pointedly named ‘Schlaraffenland’, the fool’s paradise. Rising above all - quite literally at the close when she delivered her aria of reconciliation - was Luci Briginshaw’s Fennimore, whose sweet, light soprano perfectly captured the dream of liberation.

Ronald Samm (Olim).

Ronald Samm (Olim).

Historically, as we know with hindsight, Kaiser’s utopia remains just that, even though his play ends with a ‘miracle’. And, so the ending poses further challenges, for while Der Silbersee is a social commentary it is also a fantasy, and a production must create a gradual transition from realism to symbolism. In this way, Der Silbersee is closer to Die Zauberflöte than to Die Entführung aus dem Serail. Conway’s solution is to drape his cast and chorus in silver-foil cloaks, but this does not really effect a mediation between life and dreams, such as Shakespeare achieves in A Winter’s Tale, when Paulina summons the ‘statue’ of Hermione to life: ‘ Music, awake her; strike!/ ‘Tis time; descend; be stone no more; approach;/ Strike all that look upon with marvel.’

Kaiser prophesied: ‘The music to Der Silbersee is something immortal, because art lives longer than all politics.’ Can we, today, believe in Der Silbersee’s concluding promise of escape and redemption? That, through the intervention of fate and the wheel of fortune, the hours of night will give way to the dawning of the light? Does our present foretell of future catastrophe, or can the social collectivism which Kaiser and Weill espouse ‘save’ us? I’m not sure that Conway makes us ask, or answer, this question, but if a production of Der Silbersee is to transcend its specificity then surely it must?

I suspect, however, that Der Silbersee has irreconcilable feet in both past and present; moreover, present-day German audiences surely respond differently to its historical particulars, in ways not accessible to Anglophone audiences. That said, audiences around the UK should be grateful to Conway and ETO for the opportunity to reflect on such matters. Can we transform ourselves and our world? Does the future offer hope?

Claire Seymour

Kurt Weill: The Silver Lake (Der Silbersee)

Olim - Ronald Samm, Severin - David Webb, Fennimore - Luci Briginshaw, Frau Luber - Clarissa Meek, Baron Laur/Lottery Agent - James Kryshak, Shopgirl 1 - Abigail Kelly, Shopgirl 2 - Hollie-Anne Bangham, Gravedigger 1 - David Horton, Gravedigger 2 - Andrew Tipple, Youth 1 - Jan Capinski, Youth 2 - Bradley Travis, Ensemble (Rosanna Harris, Amanda Wagg, Maciek O’Shea), Narrator - Bernadette Iglich, Streetwise Opera; Director - James Conway, Conductor - James Holmes, Designer - Adam Wiltshire, Lighting Designer - David W Kidd, Orchestra of ETO.

Hackney Empire, London; Saturday 5th October 2019.