13 Oct 2019

A humourless hike to Hades: Offenbach's Orpheus in the Underworld at ENO

Q. “Is there an art form you don't relate to?” A. “Opera. It's a dreadful sound - it just doesn't sound like the human voice.”

Q. “Is there an art form you don't relate to?” A. “Opera. It's a dreadful sound - it just doesn't sound like the human voice.”

My preparatory research in advance of Emma Rice’s new production of Offenbach’s Orpheus in the Underworld at English National Opera was inauspicious. Her dismissal of opera as an artform, in an interview in The Guardian in 2012, together with her recent remark to the newspaper’s associate editor (culture) Claire Armitstead that after agreeing to take on the production she found herself thinking, “‘Bloody hell, how do I get through this?’ It would be easier if I knew how to read a score”, didn’t inspire confidence.

Pre-performance, a programme article informed me that Rice’s starting point for re-writing the spoken text of the libretto - the new English lyrics have been supplied by Tom Morris - had been to put the French text through Google Translate and that, as she chopped and changed the opera, particularly Act 2, ENO’s Artistic Director Daniel Kramer had had to remind her, “let’s get the music back in. We are an opera house!” Returning to the score Rice seems to have been quite surprised to find that “yes, there was all this lovely music I’d left out so back it went in and I cut a lot of the text I’d written”. Not enough of the latter, was my post-performance assessment.

Mary Bevan (Euridice). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Mary Bevan (Euridice). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Rice seems to have taken the fact that Offenbach didn’t leave us a definitive score as evidence of a schism in the Werktreue pact between composer and performer, and as licence to act as co-creator and ‘rectifier’. “I started to look at the two-act and the four-act versions and at the three English translations of the libretto that I found. None of them said what I wanted to say.” What about what Offenbach wanted to say?

Rice is probably not inaccurate to observe that “A lot of the satirical nineteenth-century French jokes just don’t work”. Nowadays, Offenbach’s mockery of myths and Gods, and of Gluck’s presentation of them, is unlikely to prompt either a giggle or the disgruntled self-righteousness of the critic, following the 1858 premiere at the Bouffes-Parisiens, who condemned the operetta as a ‘'profanation of holy and glorious antiquity’. And, while Flaubert had been prosecuted for obscenity in 1856 for his daring depiction of the adulterous Emma Bovary, marital discord and infidelity no longer raise eyebrows.

Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Photo credit: Clive Barda.

But, what Offenbach really had in his sights was the Second Empire elite and his operetta’s revolutionary energy derives from its lampooning of the veneer of glamour and wealth which masked corruption and authoritarianism. A satire on pompous politicians and their vices surely has some contemporary relevance? After all, Act 2 ends with the gods’ declaration that their ‘strong’ leader is taking them all down to hell. Quite.

Rice seems to have decided otherwise. I was interested to read a comment by the Spectator’s Kate Maltby, written in October 2016 following Rice’s departure from her position as Artistic Director of the Globe Theatre: ‘Rice seemed to view Shakespeare’s texts as obstacles to be avoided, rather than challenges to be solved. […] Why probe a Jacobean playwright’s blindspots if you can just rewrite them?’ Plus ça change …

Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Don’t be misled by the balloons. Courtesy of the valiant ENO Chorus we have balloon bees, balloon sheep, balloon tutus, balloon clouds, even a taxi borne aloft by balloons, but, set in Soho in the 1950s, Rice’s production is no party. During the overture she presents a ‘pre-story’ which sees the genuinely enamoured Orpheus (Ed Lyon) and Euridice (Mary Bevan) wed, conceive a child and then suffer a tragedy which results in marital breakdown. A wreath spelling BABY casts a depressing and not entirely tasteful shadow on proceedings.

Lucia Lucas (Public Opinion) and Ed Lyon (Orpheus). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Lucia Lucas (Public Opinion) and Ed Lyon (Orpheus). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

The traumatised Euridice runs off with ‘shepherd’ Aristaeus (Alex Otterburn’s Pluto in disguise) and Public Opinion (Lucia Lucas) - a London cabbie who has ‘The Knowledge’ - persuades Orpheus to hop into his TX4 and head for Hades to win her back. First, though, we stop off in Olympus, a luxury lido where the gods are bored and behaving badly. Ambrosia and amorous adventures are no longer gratifying, and Jupiter is a sexual predator. When the Hackney cab rolls up in Hell, we find Euridice imprisoned in a hovel, the horrors of which are exacerbated by her inebriate gaoler, John Styx (Alan Ope is brilliantly sinister but it’s not clear why he laments his lost kingship of Poland, rather than Boeotia?).

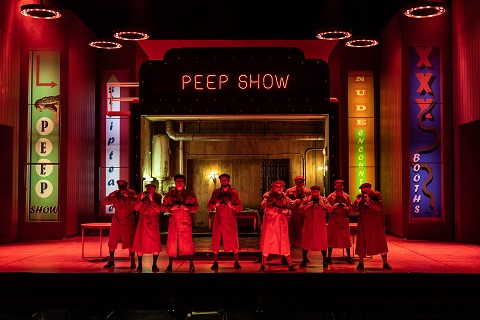

Forced to work in a sleazy Peep Show, Euridice is leered at by dirty old men-in-macs and a beer-bellied Bacchus (the ENO Chorus’s Peter Willcock). Where Offenbach’s score gives us the sparkle of life-affirming laughter, Rice gives us misogyny and #MeToo sexual abuse. Euridice sings: “Dance! Till you feel your soul goes. Dance until control goes and you can’t ask why. Embrace the frenzy and the pain until the mad becomes the sane.” Infernal it certainly is, but not the time and place for a can-can.

Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Rice declares, “if I do one thing I will make people care about [Orpheus and Euridice]”; it might have been better if she’d made us laugh. Even our London cabbie’s humour fails, though Lucas does her best with the ponderous dialogue. And, if we do care, then it’s because Lyon and Bevan, and the rest of the strong cast, sing with courage and commitment, not because of Rice’s meddling.

Alex Otterburn (Pluto). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Alex Otterburn (Pluto). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Bevan’s beautiful warm soprano gives some weight to Rice’s conception of Euridice as a woman wronged, and Lyon is a sympathetic Orpheus in contrast to the slimy sleaze-balls who plague his beloved. Alex Otterburn’s campy Pluto flicks his forked tail with aplomb and delivers an agile performance. Ellie Laugharne looks and sounds good as the gold-lame hot-pant wearing Cupid, though her words evaded me, and Idunnu Münch sings Diana’s decidedly unchaste aria superbly. Judith Howarth (Venus) and Anne-Marie Owens (Juno) are strong vocally but under-directed, though the latter gives a masterclass in how to declaim the spoken dialogue. Keel Watson dons a medal-decorated white bathing-gown over his combat fatigues as the bellicose Mars. Dressed in Bermuda shorts and drawing on a cigar, Willard White sings resonantly but is a rather stern and disengaged Jupiter; perhaps he was disaffected by having to sing lines such as “When I wiggle my bum, my little wings begin to hum” in the fly-duet.

Lizzie Clachan’s set and Lez Brotherston’s costumes are eye-pleasing and colourfully lit by Malcolm Rippeth. In the pit, Sian Edwards does her best to serve up some sparkle, but the stop-starts caused by the dull (amplified) dialogue take the edge of the dramatic pace. Glitter and be gay this Orpheus is not. By the end, the balloons had well and truly burst.

Claire Seymour

Eurydice - Mary Bevan. Orpheus - Ed Lyon, Public Opinion - Lucia Lucas, Pluto- Alex Otterburn, Jupiter - Willard White, Juno - Anne-Marie Owens, Cupid - Ellie Laugharne, Diana - Idunnu Münch, Venus - Judith Howarth, Mars - Keel Watson, John Styx - Alan Oke; Director - Emma Rice, Conductor -Sian Edwards, Set Designer - Lizzie Clachan, Costume Designer - Lez Brotherston, Lighting Designer - Malcolm Rippeth, Choreographer - Etta Murfitt, Sound Designer - Simon Baker, Orchestra and Chorus of English National Opera.

English National Opera, London Coliseum; Friday 11th October 2019.