31 Oct 2019

The Dallas Opera Cockerel: It’s All Golden

I greatly enjoyed the premiere of The Dallas Opera’s co-production with Santa Fe Opera of Rimsky-Korsakov’s The Golden Cockerel when it debuted at the latter in the summer festival of 2018.

I greatly enjoyed the premiere of The Dallas Opera’s co-production with Santa Fe Opera of Rimsky-Korsakov’s The Golden Cockerel when it debuted at the latter in the summer festival of 2018.

Since that outdoor New Mexico venue is celebrated for its open upstage wall that affords sunset views of the Sangre de Cristo mountains, I wondered how the scenic “environment” might adapt to an indoor proscenium house. The answer is, quite wonderfully well.

If anything, I found Gary McCann’s industrial grid work scenic elements even more effective. Although appearing more compact on the Winspear Opera House stage, the whole artful edifice seemed better placed, especially the sweeping skateboard-like ramp/wall stage right that also served as a projection screen.

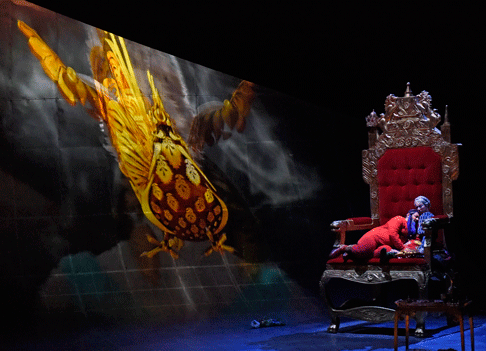

For Act II’s “mountain pass,” a series of broken rings and girders was added upstage, a stacking of half-finished roller coaster loops perhaps subtly suggesting a rooster’s tail. The raked stage floor included an effectively used trap door, that allowed for the loopy entrance of King Dodon, seated with legs splayed on a greatly over-sized gilded throne, recalling (intentionally?) Lily Tomlin’s Laugh-In persona, Edith Ann, who was dwarfed by the huge chair she occupied.

Driscoll Otto’s inventive projection design remains one of the production’s glories, especially when he utilizes the upstage back wall in Acts Two and Three, after intermission. Curiously, that upstage screen was not utilized in Act One and the playing space lacked the maximal visual depth it might have had. Of course, in Santa Fe that upstage space was open to nature and was not a projectable surface, but were this production package to have further life, I would urge adding upstage projections in Act I. The animated cockerel proved an especially effective decision.

Mr. Otto’s inspired creations sometime even spilled dizzyingly onto the proscenium, and his work was beautifully complement by Paul Hackenmueller’s amazing lighting design, which was a malleable marvel of vibrant color washes, selectively deployed follow spots, dramatic side-lighting, austere down-lighting, and all manner of moody illumination that perfectly suggested just the correct atmosphere, ranging from brutally tragic to playfully comic.

Mr. McMann also provided a colorful and varied costume design, a veritable explosion of folk wear that riffs on peasant Matroyushka dolls, Orthodox religious icons and pompous royalty with equal aplomb. The King/Tsar was presented as the emperor that has no clothes on, caped but with a distended beer-belly in his red BVD’s, an inspired touch. And a final costume reveal near the end suddenly alters the tone and period, and injects contemporary resonance into the political satire, should any still be needed.

With an almost entirely new cast, director Paul Curran has recreated and further enhanced an excellent arsenal of stage business and blocking. The use of the huge throne was notably daffy, with the King, his dimwitted progeny, General Polkan, and even housekeeper Amelfa clambering on, over, and off this huge piece, ducking under armrests, standing on the seat and arms, leaping to the floor, and clambering back up on the rungs of the braces over and over again. That they did this entertaining workout routine seemingly tirelessly is a testament to their stamina, fitness, and dedication.

I still loved that the Queen of Shemakha was announced and accompanied by a bevy of white clad showgirls brandishing white ostrich plume fans, like an upscale supper club floor act. Later, these chorines and their feathers conspired with King Dodon in a Ziegfeld-Follies-routine-gone-wrong, which found the dippy monarch hilariously bumping, grinding, and popping a few outrageous hip moves that had the audience giddy with amusement.

Mr. Curran not only used the chorus ingeniously and meaningfully during longer orchestral passages to visualize the action, but also devised well-choreographed interplay between the principals that began as lighthearted political commentary and then morphed into sobering tragedy as the stakes were inexorably raised.

Conductor Emmanuel Villaume had led a most persuasive reading in Santa Fe and he has only honed his interpretation to an even more telling rendition. Nothing about this challenging score eludes him or his finely tuned group of Dallas instrumentalists. The composer remains an acclaimed orchestrator to this day, and Maestro Villaume elicited every drop of color and variety of effect from this wide-ranging score. The exquisite woodwind soloists are arguably first among equals for their spirited contributions, many of which conveyed an effortless exoticism and piquant commentary.

The brass fanfares and motifs were commandingly rendered, and the percussive effects were tastefully stirring. The strings could effortlessly segue from regaling us with banks of lush and ravishing ensemble work, to providing sardonic, characterful commentary. This was an exceptional reading of a knotty, difficult piece, and Villaume proved to be completely in command of his large forces, to include Alexander Rom’s exquisitely prepared chorus. The soloists, too, were uniformly excellent.

Two holdovers from their Santa Fe triumph were Barry Banks and Kevin Burdette. Of the former I had written: “Barry Banks was born to play the Astrologer.” I remain convinced of that fact, and if anything, Mr. Banks’ utterly secure, freely produced tenor rang out even more thrillingly on this occasion as he made child’s play of the role’s forays into the stratosphere, without ever sacrificing beauty of tone. And Mr. Burdette seems to be having even more fun than before as General Polkan, characterized by his rock-solid bass singing, coupled with securely delivered Cassandra-like prophecies, loose-limbed physicality, and a most winning, mustache twitching comic impersonation.

Nikoloy Didenko’s bass-baritone anchored the show as the clueless, pliable King Dodon. At first, his delivery seemed just a bit muted, the rich tones of his lower and middle register thinning out a bit at the very top. At the matinee I attended, Mr. Didenko warmed substantially to his task as the show progressed, and he was soon firing on all cylinders, the top turning over with sheen and power. Although his voice has good thrust and has a nice hint of metal, this is a somewhat lighter instrument than I have experienced in the part, although no less effective, since it was performed with unerring musicality. Best of all, Nikoloy was a committed, no holds barred comedian, able to throw himself into the wide-ranging serio-comedic demands of this lengthy role with commendable abandon.

Viktor Antipenko (Prince Guidon) and Corey Crider (Prince Afron) were true luxury casting as the King’s boneheaded sons. Hmmm, a clueless, uninquisitive, vain head of state with two clueless male offspring…where have we encountered this before? But I digress…Mr. Antipenko deployed a freely ringing Heldentor which imbued the brief part of Guidon with burnished vocal pleasures, while Mr. Crider’s imposing bass-baritone pinged off the back wall with powerful beauty. Between the two of them, they not only delivered some of the show’s best vocalizing, but also wholeheartedly bought into the political mockery and silliness of purpose.

Jeni Houser’s pliant, soaring coloratura soprano was so assured and attractive in her offstage declamations as the titular Cockerel, that I wished she had been given more to sing. Lindsay Ammann’s rolling, robust contralto ably served and informed the character of the servant Amelfa. Ms. Ammann’s rich intonations at the lowest reaches of the part were especially impressive, although her registers are well knit and uniformly, powerfully pleasing. Lindsay’s ‘goof’‘with a “parrot” prop was particularly memorable for its ingenuity.

Rounding out the cast was the Queen of Shemakha as embodied by the delectable coloratura soprano, Olga Pudova. First, she is an attractive, pert, petite young woman with the requisite beguiling physical presence. There are precious few sopranos who could not only sing the role this ravishingly, but could also simultaneously, uninhibitedly, strip from a flowing gown and headdress to a skimpy, two-piece harem showgirl bikini.

Ms. Pudova’s gleaming voice is on the smaller, lyric side, but she has a superior sense of line and focus that easily communicates in the house. Her coloratura is flawlessly rendered and her sly manner with a comic turn of phrase imbues her singing with infectious joy. While she vamped the King without inhibition, she could turn on a dime and become a deadly, manipulative siren when the drama demanded it.

If her finely spun phrases in alt were her crowning achievement, she could not quite summon the requisite ominous weight for the more sobering dramatic (and musical) turn of events. Still, Olga emphatically proved that she was the undisputed Queen of all she surveyed, and the audience responded with enthusiastic acclaim.

What a pleasure to encounter this worthy production again and have the opportunity to appreciate so many artists new to me that made for such a rewarding afternoon in the theatre. The Dallas Opera is to be lauded for bringing to life this operatic rarity, a Cockerel that was golden in every way.

Happy Tenth Anniversary at the Winspear venue. And many more.

James Sohre

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov: The Golden Cockerel

Astrologer: Barry Banks; King Dodon: Nikoloy Didenko; Prince Guidon: Viktor Antipenko; General Polkan: Kevin Burdette; Prince Afron: Corey Crider; First Boyer: Jay Gardner; Second Boyer: Christopher Harrison; Golden Cockerel: Jeni Houser; Amelfa: Lindsay Ammann; Queen of Shemakha: Olga Pudova; Conductor: Emmanuel Villaume; Director: Paul Curran; Set and Costume Design: Gary McCann; Lighting Design: Paul Hackenmueller; Projection Design: Driscoll Otto; Chorus Master: Alexander Rom