Aschenbach’s gesture, in the opening scene of David McVicar’s astonishingly

hypnotic production of Benjamin Britten’s final opera, anticipates a symbol

which does not appear until the latter scenes of Mann’s text, when,

following the vulgar musical performance of a group of ‘beggar virtuosi’ in

the front garden of the Hotel des Bains, he steals a glance at the young

Polish boy Tadzio and reflects, in what Mann describes as ‘that sober

objectivity into which the drunken ecstasy of desire somethings strangely

escapes’: ‘He’s sickly, he’ll probably not live long.’ Into Aschenbach’s

mind intrudes a memory of his parents’ house, many years ago: ‘he suddenly

saw that fragile symbolic little instrument as clearly as if it were

standing before him. Silently, subtly, the rust-red sand trickled through

the narrow glass aperture, dwindling away out of the upper vessel, in which

a whirly vortex had formed.’

[1]

Thus, with subtle symbolic foreshadowing, McVicar begins to tell Mann’s

and Britten’s tale. Like the rust-red hair shared by the sinister figures

who cross Aschenbach’s path in the action which unfolds, the vanishing sand

is ominous. “My mind beats on and no words come,” sings Aschenbach. Time is

running out: “No sleep restores me.” Repeated references to the passing

hours infiltrate Mann’s text and in McVicar’s production the defiant clock

makes its presence felt, nowhere more so than when an outsize pendulous

clock-face descends and hangs in suspended motion above the gondola in

which Aschenbach sits, agitatedly, his attempt to depart from Venice

thwarted by the misdirection of his luggage.

The Hotel Barber may promise to restore his youthful looks but Aschenbach’s

creative spirit is sterile, guttering like the candles on his desk. His

journey to the South, driven by the Strange Traveller’s encouragement that

he might quench his spiritual thirst - “a leaping, wild unrest, a deep

desire! […] a sudden desire for the unknown” - is an attempt to return to

the past: “I am led to Venice once again,” Aschenbach sings, later fearing,

“O Serenissima, be kind, or I must leave, just as I left before.” But, the

sand runs steadfastly downwards.

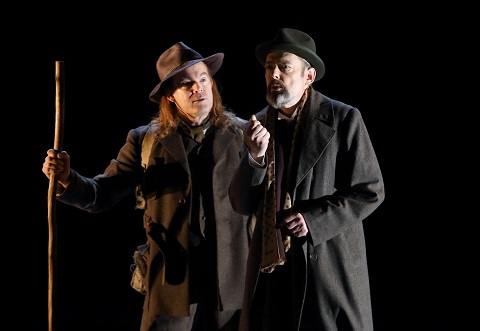

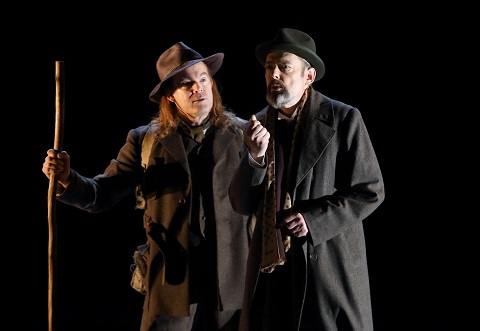

Gerald Finley (Traveller) and Mark Padmore (Aschenbach). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Gerald Finley (Traveller) and Mark Padmore (Aschenbach). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

The tremendous achievement of McVicar, his creative team and a superb,

extensive cast, is to simultaneously portray the mythical aura of the city

of Venice and present a disturbing portrait of a psychology laid bare. The

naturalism of the 1910s setting and the astonishingly detailed realism of

Vicki Mortimer’s designs are intruded by the surreal, the grotesque and the

demonic. The result for Aschenbach is catastrophic.

McVicar, Mortimer and lighting designer Paul Constable exercise masterly

control of these two intersecting energies, capturing in form and flux both

the wretched reality and the mythic grandeur of Venice. A prevailing

darkness is punctuated by sudden illuminations of light. The golden glow

that greets Aschenbach when the Hotel Manager reveals the glorious view

from the window of his room, for a brief moment bathes the drama in hope.

But, elsewhere, for all the vivid colour that Apollo’s sunrays reveal, the

Lido often seems to shimmer with a secret sickness. When the vista opens to

reveal the glistening teal waters of the limitless sea, the easefulness

that the brightness offers is tempered by a thick, unmoving green glow. The

sky above is cloudless, but it is muted by a patina of soft grey or pink

flush.

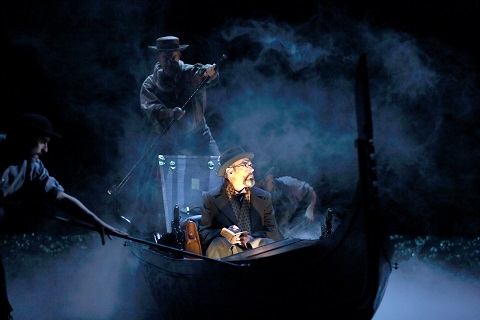

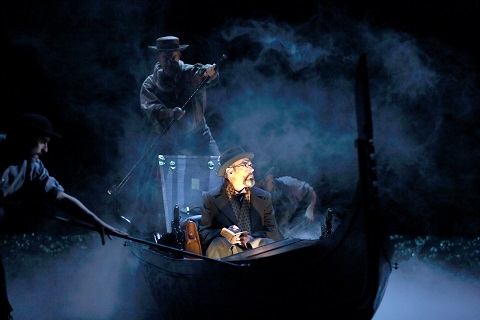

When Aschenbach arrives by gondola through the swirling mists, we can

almost smell the pungency - what he later describes as a “sweetish

medicinal cleanliness, overlaying the smell of still canals”. Even the

clarion purity of the cry of the Strawberry Seller (Rebecca Evans) as she

advertises her wares is deceptively sweet, for her red fruit is laden with

choleric juices.

Gerald Finley (Gondolier) and Mark Padmore (Aschenbach). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Gerald Finley (Gondolier) and Mark Padmore (Aschenbach). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

As within Aschenbach’s own imagination and consciousness, nothing is still

in the city or its lagoon. A stage-length gondola is expertly manipulated

across and around the stage, twisting through the inky blackness; beyond

pillars and arches which slide with the slick slipperiness of the boatman’s

oar we glimpse piazzas, arches, basilicas, as our emblematic Charon carries

Aschenbach towards his fate. The stagnant waters dominate, and McVicar

repeatedly lets a black drop fall, to isolate Aschenbach as he sinks

further into the abyss of his own mind and soul. Venetian hordes bustle and

barter: tourists from across Europe gather in the cafés and on the strand;

lace-sellers and glass-makers press their wares upon the repulsed

Aschenbach, crowding beneath the claustrophobic arches. The individuals of

the company excel, and deserving of especial note are Dominic Sedgwick’s

English Clerk, who is the lone deliverer of the truth of Venice’s innate

corruption, and Colin Judson’s Hotel Porter, though the latter’s

middle-aged censoriousness belies the youthfulness of Mann’s original.

Amid the restlessness, though, there is statuesque motionlessness:

in the form of the young Polish boy, Tadzio, holidaying with his mother,

the Lady of the Pearls (Elizabeth McGorian), and his siblings. And, it is

to this Hellenic apparition - what Mann’s narrator describes as ‘a

statuesque masterpiece of nature’ - that Aschenbach is drawn, a vulnerable

moth to a flame, increasingly convinced that, in the words of Mann’s

narrator, ‘it was inevitable that some kind of relationship and

acquaintance should develop between Aschenbach and the young Tadzio’.

In both novella and opera, Aschenbach is repeatedly reassured by moments,

actual or self-delusory, in which the respective gazes of man and boy are

locked together, and McVicar emphasises this ‘looking’ and ‘knowing’, not

just through the frighteningly confident stare with which Leo Dixon, First

Artist of the Royal Ballet, fixes the elderly writer with eyes that tempt

and dare, but also through more subtle symbols: the small round spectacles

which Aschenbach clutches and fumbles; the Brownie box-camera positioned on

the beach, its single-focus lens shrouded from the sun’s heat. “So, my

little beauty, you notice when you’re noticed do you?” Aschenbach’s

imagined private contact with Beauty hypnotises him, inducing a mental,

visual and moral stagnation: he cannot look away and, incapable of moral

resolution, abandons himself to his apocalyptic destiny.

As the self-tormented protagonist, Mark Padmore gives a performance of

unwavering acuity and accomplishment. For all his achievements as Bach’s

Evangelist and as an interpreter of Schubert’s and of Britten’s songs, he

surely has done nothing finer than this. The sweetness of his tenor, which

launches lightly and cleanly into the ethereal but also communicates the

pain and pathos of the actual, makes his Aschenbach a more sympathetic

sufferer than we might imagine possible.

Aschenbach may be isolated from his fellow travellers in Venice but the

directness of Padmore’s delivery, as he dominates the forestage, and the

exemplary articulacy of his diction, hold the fictional artist and the real

audience in a compelling communion. Mann described his protagonist’s inner

maelstrom, with autobiographical resonance, as a combustible creativity in

which the thoughts and spirit of the writer’s aged and youthful self,

circled each other animatedly.

[2]

And, this creativity, which is both fertility and conflagration, is what

Padmore, and McVicar, capture so persuasively. Padmore’s Aschenbach is not

so much animated as agitated and consumed, as evidenced by the cruel glow

of barber’s red cheek-rouge. The writer’s descent from novelistic

speculations and the belief that beauty will enable him to “liberate from

the marble mass of language the slender forms of an art”, to the desperate

recognition that he “can fall no further”, is consummately controlled and

paced.

Leo Dixon (Tadzio). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Leo Dixon (Tadzio). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

At the start Padmore demonstrates surprising depth and vigour of voice, as

when he celebrates his reputation - “I, Aschenbach, famous as a

master-writer, successful honoured, self-discipline my strength”. It’s an

almost fiery self-assertion which seeks to deny and defy encroaching

self-knowledge: “Why am I now at a loss? … Would not the light of

inspiration had not left me.” During his Act 2 pursuit of Tadzio and his

family through the fetid waterways and alleys of Venice, occasionally

Padmore is subsumed within the acrid agitation. But, it is the tenor’s

vocal nuance, perspicacity and control which most astounds: that, and the

stamina - this is an enormously demanding sing and Padmore’s tenor is no

less penetrating or well-supported at the excoriating close of the opera

than it was three hours previously, when Aschenbach had sat alone in his

darkened study.

‘“You see, Aschenbach has always only lived like this” - and the speaker

closed the fingers of his left hand tightly into a fist - “and never like

this” - and he let his open hand hang comfortably down along the back of

the chair,’ reports Mann’s narrator. And, so, Padmore’s hands in many ways

communicate Aschenbach’s distress and demise. Initially, he holds himself

with the rigid conformity of his class, hand behind back, spine ram-rod

rigid. Later, he grips his ornate leather-bound notebook, in which he seeks

to translate his emotive response to Tadzio’s beauty into Platonic art,

with clenched fingers; similarly, he contorts his hat’s rim and twists its

crown in febrile fists. And if, when accepting the offerings of the city he

exults as “Serenissma”, Aschenbach’s arms are outstretched, his palms open,

then he later acknowledges his moral degeneracy with the same welcoming, or

resigned, gesture.

Dixon’s Tadzio is introduced to us as a ‘real’ boy, somewhat petulant,

proud and aware of the effect of his posture and pose. In fact, McVicar

might have made the Polish family’s entrance more markedly gaze-grabbing,

for they seem to slip into the hotel foyer without undue notice; only in

Aschenbach’s feverish imagination does Tadzio almost instantly become an

immortal emblem of Hellenic beauty and form. And, what is so compelling

thereafter is the way the statuesque is always hovering on the cusp of

motion: this Tadzio is the union of art and life for which Aschenbach

longs.

Tim Mead (Apollo), Mark Padmore (Aschenbach). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Tim Mead (Apollo), Mark Padmore (Aschenbach). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

McVicar does not shy from the potential difficulties posed by the dance

elements of Britten’s opera and, just as the opera assimilates both realism

and surrealism, so the dance segues seamlessly from naturalism to artifice.

In the children’s beach games, cartwheels and tumbles twist into pirouettes

and entrechats, the youths’ athleticism suggesting both freedom and

rebellious danger. Dixon’s duets with Olly Bell’s Jaschiu shift between

aggression and sensuality. The crouches, curves and curlicues are quite

simply mesmerising to behold. The Games of Apollo have a choreographic

persuasiveness which beguiles. I was not entirely convinced, though, by

McVicar’s notion of an Apollo-cum-gym teacher;

Garsington's

2015 production seemed more forthright and more successful in this regard.

But, Tim Mead was penetrating and dulcet in equal measure, if a little dour

for the sun God.

From his first uncanny entrance, as the Stranger-Traveller in the

graveyard, understated but suggestive in his intimations to the troubled

Aschenbach, Gerald Finley injected the grotesque, ghostly and mysterious

into the drama. His incarnations accrued symbolic and disturbing resonance:

his lewd, lecherous Elderly Fop appalled; the vanishing gondolier alarmed;

the crude balladeer - the Leader of the Players - shocked, as much for the

faux-dwarf deformity that he relished brandishing as for the menacing

taunt, “How ridiculous you are!”, with which he and his troupe flagellated

the flinching Aschenbach.

Gerald Finley (Leader of the Players). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Gerald Finley (Leader of the Players). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

The culmination of Aschenbach’s struggle to reconcile the aesthetic with

the homoerotic is a Dream sequence of terrifying viscerality. Apollo and

Dionysus fight for supremacy as Aschenbach writhes on a bed between them;

Tadzio mounts the sleeping Aschenbach’s counterpane and strikes a pose of

proud confrontation.

Lee Dixon (Tadzio). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Lee Dixon (Tadzio). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

But, McVicar and Padmore save something, perhaps everything, for the

opera’s closing sequence, which is both transcendent (symbolic and mythic)

and real (psychologically penetrating). Dixon’s beautifully muscular Tadzio

stands upright - poised or posed - against the horizontal line where the

sea meets the sky: a symbol of the Beauty which exerts a fatal fascination

over Aschenbach’s fading creating imagination. The boy is a ‘perfect’ form,

but one which leads Aschenbach into the formless nothingness of the

Venetian waters, and on to the sea, and onwards to oblivion.

In Mann’s novella, Aschenbach strains to identify the young boy’s name: is

it ‘Adgio’, or ‘Adgiu’, with a long u, the ‘euphony

befitting to its object’? In the opera, the children’s affectionate

“Adziù!” merges with the demonic cries of Dionysus's “Aa-oo”. The Hellenic

idol, Tadzio, has a name which trickles like the sands of time: Adziù -

Tadziu - Todesengel. The angel of death. But, even as we watch Padmore’s

Aschenbach slump into eternal slumber, we see Dixon’s Tadzio scoop and

spin, an emblem of Beauty eternal. And, we remember that Aschenbach,

watching the children’s beach games, had rejoiced: “Ah, how peaceful to

contemplate the sea, immeasurable, unorganised, void. I long to find rest

in perfection.”

Claire Seymour

Gustav von Aschenbach - Mark Padmore, Traveller/Old Gondolier/Hotel

Manager/Elderly Fop/Hotel Barber/Leader of the Players/Voice of Dionysus -

Gerald Finley, Voice of Apollo - Tim Mead, Tadzio - Leo Dixon, Lady of the

Pearls - Elizabeth McGorian, Jaschiu - Olly Bell, Strawberry Seller

-Rebecca Evans, Lace Seller - Masabane Cecilia Rangwanasha, Danish Lady -

Elizabeth Weisberg, English Lady - Katy Batho, Russian Nanny - Rosie

Aldridge, German Mother - Hanna Hipp, Russian Spinster - Amanda Baldwin,

French Mother - Rebecca Lodge Birekebaek, Hotel Porter - Colin Judson, Boy

Player - Andrew Tortise, Glass Maker - Sam Furness, Steward - Andrew

O’Connor, English Clerk - Dominic Sedgwick, German Father - Michael

Mofidian, Lido Boatman - Byeongmin Gil, Russian Father - Dominic Barrand,

Russian Boy - Mathew Prichard, Tadzio’s Sisters - Corey Annand/Alice

Guilot, German Boy - Lewis Bondu, Polish Governess - Sirena Tocco, French

Girl - Adrianna Forbes-Dorant, Russian Girls - Fleur Hinchchliffe/Henrietta

Howley, Dancers (David Stirrup, Arnau Velazquez, Aitor Viscarolasaga López,

Hayden Davis, Euan Garrett, Matthew Humphreys, Zavier Linstrom, Leonardo

McCorkindale, Casper Mott, Alfie Pearce, Harry Sills), Actors (Josephine

Arden, Irene Hardy, Marcos James, Simon Johns); Director - David McVicar,

Conductor - Richard Farnes, Choreographer - Lynne Page, Designer -Vicki

Mortimer, Lighting Designer - Paule Constable, Associate Director - Leah

Hausman, Associate Choreographer - Gareth Mole, Orchestra of the Royal

Opera House.

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Thursday 21st November

2019.

[1]

Translated by David Luke, ‘ Death in Venice’ and Other Stories (Secker & Warburg,

1900)

[2]

‘Sein Geist kreiste, sein Gedächtnis warf uralte, seiner Jugend

überlieferte und bis dahin niemals von eigenem Feuer belebte

Gedanken’, in Die schönsten Erzählungen der Welt (The most

beautiful stories in the world ) (1938).