31 Jan 2020

Seductively morbid – The Fall of the House of Usher in The Hague

What does it feel like to be depressed? “It’s like water seeping into my heart” is how one young sufferer put it.

What does it feel like to be depressed? “It’s like water seeping into my heart” is how one young sufferer put it.

Patrons trickling into the theatre for Opera Melancholia heard anonymous quotes such as this one, to live chamber music by Philip Glass and Glass-inspired compositions by Daniël Hamburger. The words with which young adults tried to capture melancholy were poignant, but it was the somber pieces, especially the mournful cello and hollow percussion of Tissue No.1, that filled the house with gloom and set the scene for the main program.

Opera Melancholia is the latest production by OPERA2DAY, a small company based in The Hague that repeatedly gives its big sister in the capital a run for its money. It’s a thoughtfully constructed, progressively unsettling exploration of the nature of depression built around Glass’s opera the Fall of the House of Usher. According to the company, the work has never been staged in the Netherlands until now. Glass’s mesmerising opera is a fairly faithful adaptation of Edgar Allan Poe’s grisly tale, which lends itself to countless interpretations. While visiting his dejected friend Roderick Usher, Poe’s nameless narrator helps him entomb his twin sister Madeline in the family vault when she succumbs to a mysterious illness. Not having really died, however, she leaves her coffin and, falling upon her brother, kills him with fright. Thus the Usher family line is extinguished, as is their stately home. The narrator just manages to cross the causeway before the house comes crashing down into the tarn that surrounds it.

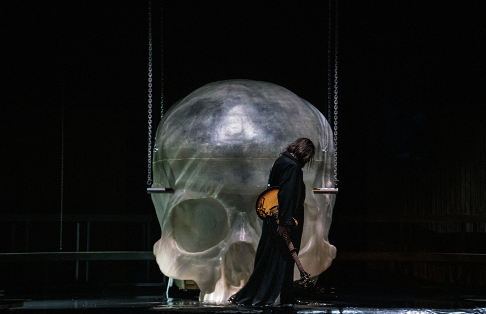

In director Serge van Veggel’s hands the opera becomes a psychiatric case study, complete with an introductory lecture by an engaging shrink and audience participation. The rotting house in the middle of the fetid lake is Roderick’s sick psyche, represented by a giant skull surrounded by an inky pond. It stands in the middle of an anatomical theatre, the kind in which cadavers were dissected for the benefit of medical students, a sober set that comes alive under Uri Rapaport’s kaleidoscopic lighting. Applying principles of psychoanalysis and Eastern philosophy, Van Veggel maps the three characters to parts of Roderick’s fractured self. He himself stands for his thinking self, or the Freudian ego, that has become disconnected from his feeling self (the Freudian id), embodied by his sister Madeline. The friend, named William in the opera, stands for consciousness or the socially acceptable superego. He’s the catalyst that forces Roderick to embrace his emotions, rather than burying them away, and heal his childhood trauma. This approach to psychotherapy probably wouldn’t bear close scientific scrutiny, but artistically it is an elegant thesis. And surely Poe, who knew a thing or two about the murky depths of the human psyche, would have approved.

If it all sounds a bit complicated, actor René M. Broeders, as the genial doctor dissecting Roderick’s mind, made it all seem plausible in his semi-improvised lecture. Be aware, if you go to a show, that his staff could question you about sadness while you’re having your pre-performance drink in the foyer, and Broeders could ask you to elaborate on your answers during his presentation. When was the last time you cried? And which piece of music best expresses melancholy? (The selections are added to a Spotify playlist. ) Responding to Broeders’ unforced humour and sensitivity, patrons were articulate and forthcoming with information, some of it rather intimate. The hall gasped when a GP reported that half of his patients presented with psychological problems, either explicit or masked by somatic symptoms. After this touching and entertaining briefing, the cast took over the stage to perform the opera/case study, and they were fantastic.

Tenor Georgi Sztojanov left a strong impression as the Usher family physician, a part which subsumed the role of the servant, originally written for a bass. William’s compassion came across in Drew Santini’s fine baritone. Brimming with optimism in the beginning, Santini grew visibly hunched as Roderick’s moroseness wore him down. In a casting master stroke, soprano Lucie Chartin seductively spun Madeline’s vocalises offstage while willowy Ellen Landa danced her onstage. Twitchy, obsessively repetitious choreography by Ed Wubbe of Scapino Ballet captured the seductiveness of the mad and the morbid. Snaking across the dirty water, her wet robe dragging behind her, Landa was a horrific and fascinating apparition. So was tenor Santiago Burgi as the unhinged Roderick, surrounded by books and bin liners stuffed with empty booze bottles, frenziedly banging out poetry on a typewriter. Van Veggel’s pitch-perfect direction certainly helped his phenomenally intense performance, but the fearless singing and artifice-free acting were all his own. Starting out slightly whiny to convey Roderick’s desperate neediness, his voice grew stronger and rounder as the “therapy” started to work. “If our souls could twine” to the dead Madeline was beautifully elegiac and when he recited Poe’s poem The Conqueror Worm (Van Veggel’s addition to the libretto) he kicked up a windstorm of manic energy.

As a successful case study, the opera doesn’t end in the destruction of the house of Usher, but in Roderick’s cure, but visually it’s still a dramatic finale that matches the musical climax, effectively constructed by conductor Carlo Boccardo. The New European Ensemble played for him with pulsating urgency. More assertive entrances whenever Glass introduces a new pattern would have propelled the musical narrative further, and at one point the orchestra overshadowed the trio of soloists, but the performance as a whole hummed with vitality. Opera Melancholica is on tour in the Netherlands, with alternating cast members, until the 19th of March. The lecture is in Dutch, but an outline in English is available. The opera is subtitled in Dutch and English.

Jenny Camilleri

Philip Glass: The Fall of the House of Usher

René M. Broeders, Physician-Director; Santiago Burgi, Roderick; Drew Santini, William; Georgi Sztojanov, Physician (Roderick on 19/2 and 11/3); Peter Rolfe Dauz, Physician (19/2, 28/2, 6/3 and 11/3); Lucie Chartin, Madeline; Emma Fekete, Madeline (3/3, 4/3, 6/3, 16/3, 18/3 and 19/3); Ellen Landa, Dancer; Dora Stepušin, Dancer (19/2 and 11/3). Gijs van Mierlo and four other actors take turns as the Child. Herbert Janse, Set Designer; Mirjam Pater, Costume Designer; Uri Rapaport, Lighting Designer; Ed Wubbe, Choreographer; Daniël Hamburger, Composer. Serge van Veggel, Director. Carlo Boccardo, Conductor. New European Ensemble. Seen at the Koninklijke Schouwburg, The Hague, on Wednesday, the 29th of January, 2020.