October 31, 2005

Big ambitions in a small town

By Andrew Clark [Financial Times, 31 October 2005]

By Andrew Clark [Financial Times, 31 October 2005]

When the curtain fell on Carlisle Floyd's Susannah in the southern Irish town of Wexford last week, it was hard to predict the embattled heroine's future. Despite her poor background Susannah was attractive enough to stand out in any crowd. But by refusing to conform to small-town standards, she was exposing herself to all sorts of risk. Had she doomed herself to a life of struggle - or opened the gate of opportunity? Floyd, an American who composed the opera 50 years ago, deliberately left the question open.

A Singing Hiker Who Scales the Heights of Mozart Opera

By EDWARD ROTHSTEIN [NY Times, 31 October 2005]

By EDWARD ROTHSTEIN [NY Times, 31 October 2005]

SALZBURG, Austria - Standing in the Barmstein mountains, not far from Salzburg, I am listening to a fourth-generation Salzburger sing Mozart in the woods. It is not exactly on a scale with next year's plans to celebrate the 250th anniversary of the birth of Mozart, this city's most famous native son. Those events will dominate the musical life of Salzburg and Vienna. Mozart's complete operas are to be performed at next summer's Salzburg Festival; Robert Wilson is designing what is bound to be a strange installation in the building where Mozart was born; multiday Mozart biking tours are planned for those who want to follow in his coach tracks; musicians will make pilgrimages to perform and audiences to listen.

Tremendous Foreboding in the Air

BY JAY NORDLINGER [NY Sun, 31 October 2005]

BY JAY NORDLINGER [NY Sun, 31 October 2005]

Elizabeth Futral, a soprano from New Orleans, is one of the best singing actresses we have. She has proved as much before New York audiences in recent seasons. Last fall, she was Strauss's Daphne, at City Opera. Earlier this month, she starred in Ricky Ian Gordon's "Orpheus and Euridice," a presentation of Great Performers at Lincoln Center. And on Thursday night, she was Lucia, at the Metropolitan Opera. The Met has again revived what may be the quintessential bel canto opera, Donizetti's "Lucia di Lammermoor."

October 30, 2005

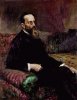

SAINT-SAËNS: Samson et Dalila

While the overture has always been a perennial concert favorite, and the symphony has always been admired, the opera has had an unfair share of detractors and critics, even during the composer’s lifetime. The opera, conceived in 1867, was premiered at Weimar in 1877, through the influence of Saint-Saëns’ friend, Liszt, and it would not be staged in the composer’s homeland until 1890. Upon closer scrutiny into the composer, one can see that the opera mirrors Saint-Saëns’ personal situation and the political struggle in France during the composer’s youth. In addition, the character of Dalila is a composite of three very influential, at times detrimental, women in the composer’s life: his mother Mme. Saint-Saëns, the singer Pauline Viardot to whom the opera is dedicated, and Augusta Holmes.

In Samson et Dalila, Saint-Saëns presents a tightly woven and seamless score from which not one note can be spared, not one instrument or voice is miscast, and no situation in the libretto not perfectly matched to the score. Saint-Saëns’ music is at times heroic, seductive, compassionate, and spiritual. The Bacchanale, the most criticized part of the work, is an orgy of sound and decadence mixed with Samson’s cry for redemption—a fitting end to the opera.

This two CD set is a budget re-issue originally recorded in July 1979, following a performance at the Théátre Antique National d’Orange. There are many worthy moments in this recording as well as some minor flaws, and the three principals, Domingo, Obraztsova, and Bruson, give a valiant and exciting performance.

Domingo, who still sings this role, had not yet developed the excessive nasal tone which would later plague him, and at the time of this recording he gave the leading character a youthful vigor and naiveté not usually found in other interpreters. Most appealing is his Act II interaction with Dalila, “En ces lieux, malgré moi…” and the Act III prayer like “Vois ma misère, hèlas.”

Unlike Voltaire’s character for Rameau’s opera on the same subject, Fernand Lemaire’s Dalila does not lust for the Biblical hero; instead, she uses her sex and allure as a weapon against the weaker Samson. This Dalila is strong, determined, and vengeful. As such, Russian mezzo-soprano Obraztsova, among her many roles, an excellent Amneris and

Azucena, would at first glance seem a good choice for this opera; her instrument is sharp without being edgy, at times careless without being unpleasant, and always exciting, but as Dalila, not always parallel to the sensuality in the music. Her rendition of “Printemps qui commence... ” is very deliberate rather than seductive or alluring; and in the opening monologue of Act II, “Samson, recherchant ma presence…” her diminuendo and chest notes are ineffective and out of character. These minor pecadillos are later redeemed in her scenes with the High Priest, “J’ai gravi la montagne…oui…déjá par troi fois…” and with Samson, “En ces lieux, malgré moi…Mon cœr s’ouvre a ta voix…Mais! Non! Que dis-je, hélas…,” and later in Act III, “Salut! Salut au juge d’Israël…Glorie à Dagon vainqueur…” following the Bacchanale.

Of the three principals, Bruson seems the least comfortable singing in French (followed by Obraztsova) but the unmistakable sound of his instrument redeems him, in particular during the scene with Dalila Act II, “J’ai gravi la montagne…Oui déjà par trios fois…,” and in Act III “Salut! Salut au juge d’Israël…Glorie à Dagon vainqueur…”

The chorus, essential to this opera, is credible—the voices always in unison, well-rehearsed, and excellently handled by Oldham. Of the supporting cast, Pierre Thau, as Abimélech, and Rober Lloyd as the Old Hebrew make the best of their respective roles, though they both sound rather detached.

The Orchestre de Paris is in top form, and is served well by Argentinean conductor Daniel Barenboim. He lavishes attention to the score, and treats every instrument as a soloist with the desired effect of the listener being able to individually, and continually hear all the notes and subtleties in the music, including those in the more complex ensembles. The deliberate pauses in the score are faithfully adhered to, and further emphasize the drama in the music. One minor comment to Barenboim’s conducting is his slow approach in several key passages, which shifts the emphasis of the music and the singing from religious fervor to a “lullaby” (Dieu! Dieu d’Israël), and from seductive to “elegant” (Printemps qui commence, Danse des prétresses de Dagon)—robbing the listener from an otherwise careful, energetic and flawless performance. Likewise, the interlude prior to Dalila shearing Samson’s hair is chillingly effective, as is Dalila’s “Mon cœr s’ouvre a ta voix,” the introduction to, and Samson’s Act III aria, “Vois ma misère, hèlas,” the much maligned Bacchanale, and others.

Overall this is a good recording to own. However, one word of caution: the budget reissue does not provide a libretto, and the breaks between the tracks are, more than once, sufficiently noticeable to be unpleasant.

Daniel Pardo 2005

image=http://www.operatoday.com/content/samson_dalila.jpg

image_description=Camille Saint-Saëns: Samson et Dalila

product=yes

product_title=Camille Saint-Saëns: Samson et Dalila

product_by=Placido Domingo, Elena Obraztsova, Renato Bruson, Pierre Thau, Chœers de l’Orchestre de Paris, Orchestre de Paris, Daniel Barenboim (cond.)

product_id=DG 477 560-2 [2CDs]

PUCCINI: Manon Lescaut

The opera had a somewhat tortured genesis, with five librettists eventually having a hand in it, including composer Ruggiero Leoncavallo and Puccini’s team-of-the-future Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica. Perhaps there are hints of this in the final product which stand between Manon Lescaut and warhorse status. Yet watching the opera from beginning to end in this handsome production from La Scala with its pair of charismatic leads, I couldn’t help but see in this opera the very same Puccini that we know and love.

There are departures. Some feel that the final act is dramatically weak by Puccinian standards. The composer nakedly stakes out “modern” territory by borrowing the musical language of Tristan und Isolde for his Intermezzo, while some of the big choral moments in the first act have a distinctly old-fashioned feel about them. And even though it is no longer than several of the other Puccini operas, Manon Lescaut has a bit of a sprawling feel to it which separates it from the laser-like focus Puccini exhibits in later titles.

Yet when the muse strikes, Puccini is as potent as anywhere. Des Grieux’s wooing of the lovely Manon in act one, the lover’s exchanges in act two, the gorgeous Intermezzo, the stunning parade of fallen women in act three, and the pair’s cries of desperation in the final act are all as affecting as any such passages in the Puccini canon.

But maybe the biggest departure is in the title character herself. Mimi, Tosca, Butterfly, Minnie, Angelica, and Liu are all easy to love. They themselves love with selfless devotion. They are simple and good. They don’t deserve the cruel hand which fate deals them. Not so with Manon. Our heroine is immature, selfish, and unfaithful. Even after being given a second chance by the heartbroken Des Grieux, when they desperately need to flee from her wealthy, elderly lover’s estate, she takes extra time to gather up jewelry and various treasures with which she cannot bear to part.

But for me, all these faults in some ways makes Manon all the more compelling, because they make her seem real. I love Cio-cio-san, but how many fifteen year-olds do you know with that amazing level of maturity? The teenaged girls I know are a lot closer to Manon!

This particular representation of the opera has just about everything going for it. The production, filmed at La Scala in 1998, is a lavish period staging with costumes as beautiful as museum pieces, and sets which bring the story vividly to life.

But even more important are the leads. One could hardly imagine a more handsome Des Grieux than Jose Cura or a more beautiful Manon that Maria Guleghina. They are picture-book leads. Neither gives a cookie-cutter performance, and these are not cookie-cutter voices. Cura’s tenor sounds more like a baritone with (great) high notes, and his vocal mannerisms—most which don’t bother me—are very much in evidence. Guleghina is shown at her best here. She is a singer with a huge voice, but one which, at times, can seem to spin out of control. Here she keeps it tamed for the most part. It is always a voice which sounded mature in comparison with her youthful appearance, with a fairly wide vibrato, especially in loud passages. Maybe that angelic face here distracted me. But if it did, so be it! Marco Berti, now a regular lead at the Metropolitan Opera, sings the small role of Edmondo in the first act. Lescaut is sung by Lucio Gallo, and Geronte is well sung and acted by Luigi Roni. Riccardo Muti leads the orchestra in a very fine reading of the score.

The DVD’s presentation is stylish and useful. The menu is very attractive, with a montage of scenes from the opera being acted out accompanied by music from the Intermezzo. One may select subtitles in English, German, French, Spanish, and Italian, and may select a particular act, or go directly to specific scenes within that act which are all labeled with titles from the Italian text.

I have no doubt that when Puccini sat down at his desk to write Manon Lescaut and pictured the scenes of the opera, he must have imagined them very much like this.

Eric D. Anderson

image=http://www.operatoday.com/content/Manon_Lescaut.gif

image_description=Giacomo Puccini: Manon Lescaut

product=yes

product_title=Giacomo Puccini: Manon Lescaut

product_by=Maria Guleghina, José Cura, Lucio Gallo, Orchestra e Coro del Teatro alla Scala, Riccardo Muti (cond.).

product_id=TDK DVWW-OPMLES [DVD}

Ewa Podleś — Rossini Gala

Podleś is one of those singers whose versatile instrument is as comfortable singing Tancredi, in the opera by the same name, Isabella (L’Italiana in Algieri), Rosina (Barbiere di Siviglia), Adalgisa (Norma), Eboli (Don Carlo), or La Haine in Gluck’s Armida. In fact, this singer can tackle any role she desires, and do it successfully. Her voice is dramatic, and she possesses an extraordinary technique which enables her to show off an impressive range spanning three octaves. She is a remarkable artist whose effortless singing comes through in her emotionally charged performances.

The timbre in her voice is warm, bronzed and pleasant to the ear; her ability to switch registers with great ease is well demonstrated, as in Arsace’s aria,“ A quel giorno,” springing from the depths of her being, and ending with crystal clear soprano-like high note; and the reverse is also true as in the finale of “Non temer d’un basso affetto” from Maometto II. She displays a firm, secure, staccato with short, rapidly sung notes, which Bernard Holland (New York Times, May 5, 2005) has likened to “bayonet charges.” When listening to this CD, other singers come to mind, not as a point of comparison, but as a compliment to her artistry and her ability to convey the drama, emotions, and the “Bel Canto” of what she is singing. Podleś delivers a rock solid performance—close to sixty minutes of non-stop singing, in what must have been an electrifying concert.

Podleś’ is clearly not one to please every listener—like any other singer she has her “own” mannerisms, some which are more noticeable in live performances; but the qualities of her instrument and her artistry cannot be denied. The contralto was in powerful form for this concert, and after listening to this CD her detractors will also come out her most ardent fans.

The Leopoldinum Chamber Orchestra, under conductor Wojciech Michniewski, is very effective in accompanying Podleś. This CD also includes one solo selection for the orchestra, the overture to Rossini’s Il Babiere di Siviglia.

Daniel Pardo 2005

image=http://www.operatoday.com/content/podles_rossini.jpg

image_description=Ewa Podleś — Rossini gala

product=yes

product_title=Ewa Podleś — Rossini gala

product_by=Ewa Podleś, Leopoldinum Chamber Orchestra and musicians of National Philharmonic, Wojciech Michniewsk (cond.)

product_id=Dux 0124 [CD]

Software idea could benefit opera

By Marta Hummel [News-Record.com, 29 October 2005]

By Marta Hummel [News-Record.com, 29 October 2005]

Opera, the highest of high art, is decidedly low-tech, at least as far as how a production is managed. Stage crews build sets without knowing an actor's height and weight. And rebuild them when Juliet turns out to be 250 pounds instead of 150.

Stage managers and bevies of assistants photocopy hundreds of pages of scores with hand-scribbled directions for lighting and sound and re-copy them when the directions change. Actors generally work from memory and hand written notes about their stage directions.

Barbarians as a compelling chorus

[Sydney Morning Herald, 31 October 2005]

Philip Glass's latest work is presented as a powerful morality play, writes John Carmody.

J.M. Coetzee's novel Waiting for the Barbarians is a literary masterpiece, multi-layered, rich in metaphor, allusive yet fierce in its ethical concerns.

But because of that very delicacy in its texture and, in particular, the importance for its artistic structure of the troubled dreaming of its central character, the narrating Magistrate, I was sceptical whether the librettist Christopher Hampton and the composer Philip Glass could really transform it into an opera, despite their enormous theatrical experience.

Tangier Tattoo, Glyndebourne Opera House, Glyndebourne

By Anna Picard [The Independent, 30 October 2005]

By Anna Picard [The Independent, 30 October 2005]

Like the package holidays that serve as its backdrop, John Lunn's operatic thriller Tangier Tattoo is aimed at 18 to 30 year olds. "Which 18 to 30 year olds?" I hear you ask. Let's set that question aside for now. First, a disclaimer. Having cordoned off its target audience by age, Tangier Tattoo is effectively critic-proofed. It follows, therefore, that whatever I might dislike about it can be dismissed as a by-product of my relative wrinkliness; though while we're on the subject of lost youth, it seems fair to point out that I was 30 more recently than Glyndebourne's creative team, not to mention Derek Laud of Big Brother, who was, with his younger housemate Eugene Sully, shipped down to Sussex to lend last Saturday's premiere some tabloid pizzazz.

October 29, 2005

GIORDANO: Fedora

Principal Characters:

| Princess Fedora Romazov | Soprano |

| Countess Olga Sukarev | Soprano |

| Count Loris Ipanov | Tenor |

| De Siriex | Baritone |

Synopsis

Act One

Setting: A winter night, 1881. The salon of Vladimiro Andrejevich in St. Petersburg.

Princess Fedora is waiting for Vladimiro, whom she is to marry that day. A police officer and De Siriex suddenly appear carrying Vladimiro. He has been shot. The police officer, Inspector Gretch, questions the servants. Fedora learns that Vladimiro was found wounded in a pavillion and that a man had been seen running away after the shots. The pavillion had been rented by an old woman who delivered a letter to Vladimiro earlier in the day. But that letter is nowhere to be found. Fedora swears to avenge Vladimiro’s death. Suspicions turn to Loris Ipanov, a friend of the nihilists (anarchists) and whose apartment is near the place of the shooting.

Act Two

Setting: Paris

Fedora follows Loris Ipanov to Paris to avenge Vladimiro. She holds a reception in her home, which Loris attends. Loris declares his love to Fedora; but, she appears to reject him. She informs him that she intends to return to Russia. Having been exiled, Loris cannot return with her. Desperate, Loris admits that he killed Vladimiro. She begs him to return after the reception to tell her the entire story. In the meantime, she writes a letter to Vladimiro’s father, the Russian Imperial Chief of Police, accusing Loris of the murder of Vladimiro. Loris returns later and explains that he had caught Vladimiro having an affair with his wife. Vladimiro shot him and Loris returned fire, mortally wounding Vladimiro. Fedora realizes that he was defending his honor and that Vladimiro was a cad. She convinces Loris to remain with her that night.

Act Three

Setting: A villa in the Bernese Oberland, Switzerland.

Loris and Fedora are happily in love. De Siriex arrives and informs Fedora that the brother of Loris had been arrested as a result of her letter. He dies in prison and, after hearing of his death, his mother dies of heartbreak. Stunned, Fedora realizes that she is the cause of their deaths. Loris receives letters from Russia with news of his brother and mother. A woman in Paris had apparently reported him. Fedora confesses her guilt and begs his forgiveness. He curses her. Fedora ingests poison hidden in her Byzantine cross. She dies in his arms.

Click here for the complete libretto.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/content/Byzantine_Cross.gif

image_description=Byzantine Cross

audio=yes

first_audio_name=Umberto Giordano: Fedora

first_audio_link=http://www.operatoday.com/Fedora1.m3u

product=yes

product_title=Umberto Giordano: Fedora

product_by=Renata Tebaldi, Giuseppe Di Stefano, Mario Sereni, Sofia Mizzetti. Coro e Orchestra del Teatro di San Carlo di Napoli, Arturo Basile (cond.). Live performance 14 December 1961

The Paris Opera Scene

By Frank Cadenhead [Opera Today, 29 October 2005]

By Frank Cadenhead [Opera Today, 29 October 2005]

The city-funded Théâtre du Châtelet, an operatic David to Paris Opera’s Goliath, managed to make the biggest artistic splash of the new season. Richard Wagner’s Die Walküre, which opened October 21, following Das Rheingold by two days, was generally well cast, surely conducted and, as staged by Robert Wilson, brimming with theatrical interest. The two final operas will follow in November/December with two complete cycles offered in April.

The Paris Opera Scene

With a budget many times smaller that the Paris Opera, it squeezed the Orchestre de Paris into the pit and ambitiously set off to do the entire Ring under the baton of their music director, Christoph Eschenbach. The Robert Wilson co-production has been seen in Zurich but is a welcome large-vision effort in a time when the second season of Gerard Mortier at the Paris Opera seems to be floundering.

This is the final season of Jean-Pierre Brossmann as the theater’s director, and this Ring makes a nice bookend to his first season where Robert Wilson did an impressive diptych of the operas of Gluck, Alceste and Orphée conducted by John Eliot Gardiner. Gardiner, a regular at Châtelet, also conducted Les Troyens of Berlioz, hogging most of the critical praise last season.

American audience are missing out with Robert Wilson making his career mostly in Europe. His familiar stagings — the kabuki-like stage movement, solid blue background, foreground figures in severe black, a follow-spot illuminating the head - at their best have a haunting beauty. The severe costumes by Frida Parmeggiani were striking and, despite the “abstract” stage pictures, all the Ring symbols were present: sword in tree, gold, giants, etc.

After seeing the first two operas of the Covent Garden Ring, I recently passed on an opportunity to see the third. The stage is decorated with odd metal bits, flea market furniture, garish lights and costumes looking like they were pulled from a trunk at random. The real false notes, however, came from attempts flesh out the characters. Brunnhilde as a rebellious adolescent and the over-long father-daughter kiss at Wotan’s farewell added a gratuitous Jerry Springer moment to a story already full of them. Robert Wilson views the Ring as more ritual than drama and his slow pace meshes well with Wagner’s extended, grandiloquent statements.

With a notable exception the cast was solid. The first act signaled the arrival of a first class Wagnerian soprano, Petra-Maria Schnitzer, whose high-voltage voice, a touch edgy, was also able to project the tender yearnings of her character. As Seigmund, Peter Seiffert already has his fans due to his Tannhäuser at Châtelet last season and he did not disappoint them with warm, unforced singing. A stunning performance from Mihiko Fujimura as Fricka was the most polished of the night and Stephen Milling was also outstanding as Hunding. Linda Watson, as Brünnhilde, was proceeded by so much buzz that she might have been first night nerves. Her grand entrance was unsteady but her later work suggested a fine Helden-soprano in training. In Rheingold, the Alberich was taken on by the noted baritone Sergei Leiferkus who made a substantial impact in this important role. Baritone Jukka Rasilainen was a pale Wotan and the weakest link in the cast.

Christoph Eschenbach disproves the old story that the Wagnerian orchestra must always overwhelm the singers and his restrained volume, leisurely pacing, and clear textures were a pleasure to hear The Orchestre de Paris, an often unruly bunch, was clearly aware that this was something special and played with uncommon skill. Eschenbach’s forward momentum was, however, not always felt, keeping both operas slightly off-balance.

At the Paris Opera-Bastille, a revival of Paul Hindemith’s 1926 opera, Cardillac, seen September 24, was the offering to show off Mortier’s Year Two artistic vision. Picking an opera about a serial killer has a certain attraction and the music of young Hindemith is some of his best. What it did show was a search for a “hit” more than a vision and also proved a fundamental weakness in his leadership.

Mortier made an early decision not to appoint a musical director for the opera and this task was divided between seven conductors, most of whom conduct only one opera a year and are not likely consulted about musical matters. Any full-time musical director might early on had a different opinion about where to present Cardillac. It is scored for a half-size orchestra and yet was staged, by Andre Engel, for the large stage at Bastille and not the smaller Palais Garnier. The chamber-sized music (one of the delicious interludes is for two flutes) is out of place there.

The first scene, for example, was a magnificent spectacle on stage but saw sub-par playing by the orchestra. It would be hard to fault conductor Kent Nagano — one of the seven — for the failures of the orchestra and the poor coordination of chorus and pit. Few, if any, conductors in the world have his Twentieth Century opera credentials.

The orchestra has tricky, syncopated rhythms for the entire first act and the chorus is tightly interwoven into this thorny fabric. But the staging has the chorus — full size — in such constant flowing motion, back and forth, that there are two choreographers listed in the program. As a consequence, the contributions of the chorus were consistently off-cue and the orchestra, under-rehearsed, simply glided over the syncopation.

The stage pictures were designed to please. The first act was in a handsome grand art-deco hotel but subsequent images, including one on the roofs of Paris, veered close to cliché. The story of a goldsmith who kills his clients, the opera does not have a plum central role but the ensemble of singers gathered were first rate. Baritone Alan Held was a convincing in the title role and the splendid soprano Angela Denoke sang the pallid role of the Daughter.

It was a laudable effort to return this little-heard opera to the stage and it is a grand production with epic sweep, designed to make the best case for the drama. The only area not effectively presented was the music but that, unfortunately, should be the central reason for hearing this work.

Frank Cadenhead

Paris

image=http://www.operatoday.com/content/Cardillac2.jpg

image_description=Cardillac (Photo: Eric Mahoudeau)

product=yes

product_title=Scene from Cardillac (Photo: Eric Mahoudeau)

October 28, 2005

Volksoper: Das weiße Licht des Todes

[Photo: Volksoper Wien/Dimo Dimov]

[Photo: Volksoper Wien/Dimo Dimov]

VON WALTER WEIDRINGER [Die Presse, 28 October 2005]

"Sophie's Choice" - hervorragend besetzt, das Orchester fulminant, und dennoch gibt es Langeweile.

Zugegeben: Es war ein einhelliger Er folg, den die versammelte Opern- Gemeinde am Nationalfeiertag in der Wiener Volksoper erjubelte, den man allen Beteiligten auch gönnen mochte - der Besetzung, an der Spitze Angelika Kirchschlager in ihrer wohl besten Rolle, dem Regieteam um Markus Bothe, Leopold Hager, der einen glänzenden Einstand als Chefdirigent feiern durfte, sowie dem Komponisten Nicholas Maw. Und die zentrale Szene, in der Sophie vom unsagbar grausamen Lagerarzt von Auschwitz gezwungen wird, eines ihrer beiden Kinder in die Gaskammer zu schicken, wirkt wirklich erschütternd und erzeugt Gänsehaut der unwohligsten Sorte. Doch in den drei Stunden, die bis dahin abzusitzen waren, hatte man sich gelangweilt. Und das, obwohl die Wiener Fassung, als Koproduktion mit der Deutschen Oper Berlin entstanden, von Hager im Einvernehmen mit dem Komponisten um eine gute Stunde gekürzt war.

Guaranteed to raise the roof

[Times Online, 28 October 2005] Valencia now has the largest performing arts centre in Spain, reports Neil Fisher

[Times Online, 28 October 2005] Valencia now has the largest performing arts centre in Spain, reports Neil Fisher

The new opera house in Valencia has some fantastical beasts for company. The coastal city’s science museum, all shiny white teeth and sharp, bony lines, lunges out of the River Turia. The flawless curves of the city’s new IMAX enclose a glistening hemisphere whose perfect reflection in the water creates a giant alien eyeball.

Why the fat ladies sing

Warwick Thompson [Times Online, 28 October 2005]

Warwick Thompson [Times Online, 28 October 2005]

Singing predisposes the body to put on weight, research suggests

The idea of fat sopranos — and let’s not be sexist, fat tenors as well — has been causing mirth for years. Where else but in opera could you find an athletic young warrior portrayed by a man whose love-handles flew south long ago? Or see a delicate geisha who looks as if she does sumo wrestling?

Toby Spence/Julian Milford at Wigmore Hall, London

Tim Ashley [The Guardian, 28 October 2005]

Tim Ashley [The Guardian, 28 October 2005]

It has been a good year for Toby Spence. The handsome young tenor became something of a star at this summer's Edinburgh festival with a startling performance in Benjamin Britten's Curlew River. He delivered an equally brilliant Tamino in Mozart's Magic Flute for English National Opera. Finally, we have this Wigmore Hall recital, which also marks him out as an idiosyncratic, if forceful, interpreter of Brahms and Mahler.

Brisk and bracing march through some preposterous plotting

[Daily Telegraph, 28 October 2005]

[Daily Telegraph, 28 October 2005]

Rupert Christiansen reviews the Wexford Festival Opera

Here in Wexford it's the best of times, the worst of times. The best, inasmuch as the opera festival's new artistic director, the American conductor-administrator David Agler, looks like a thoroughly good thing, with a determination to incorporate native talent and sensibly broad ideas on repertory and casting. Agler's first programme gives one of the best seasons for years, and with the complete reconstruction of the old Theatre Royal likely to start sometime in 2006, the long-term outlook is optimistic.

October 27, 2005

ROSSINI: La Cenerentola

Naxos recorded this Cenerentola in November 2004 at the Rossini in Wildbad festival. While not as punchy or pristine as a studio recording, the sound presents a good balance between vocalists and orchestra, and stage noise, often a significant detriment of live recordings, does not significantly mar the audio.

Right from the overture, however, an inexplicable dampness sets in – the electric charge which many live recordings boast remains stubbornly absent. Conductor Alberto Zedda, whose excellent booklet essay speaks to his commitment and authority, captures some fine detail, but the SWR Radio Orchestra seems to simply lack the flair and innate enthusiasm that brings out the best in Rossini’s charming score. Rossini specialists, however, will appreciate the opportunity to hear some alternative music that Zedda has identified and chosen to include in this performance

The CD cover photo suggests the primary attraction of this recording: rising star Joyce DiDonato’s sweet, agile voice. She delivers her act two canzone, Una volta c’era un re, with the grace and skill of a mature artist, all of which also characterizes her contribution to the sextet. She alone, however, can’t bring up the energy level to one that would make the whole performance take flight.

Juan Diego Florez reigns as Don Ramiro on the world’s stages now. Jose Manuel Zapata takes the role here, and though his voice doesn’t suggest he approaches Florez’s stature, he has a pleasant voice not strained at all by the role’s demands. Bruno Pratico’s Don Magnifico has some rough edges that might have been more effective as part of the theater experience; other than that, he inhabits the role with humorously gruff authority.

Naxos provides a link to an online libretto, with a note on the booklet informing us that this economy measure helps Naxos remain the “leader in the budget-priced market.”

All fine and good, but a Cenerentola that doesn’t sparkle and bounce makes for a less than appealing audio-only experience. Perhaps the staging, if captured for DVD, might have revealed more charm than this recording offers.

If Decca gets around to re-releasing at less than full price the Bartoli studio recording of a few years’ back, budget price alone won’t make this Naxos set competitive. Only as a record of Joyce DiDonato, still early in her career, can it be recommended. The more exciting prospect would be a DVD of DiDonato and Florez in a fine production of the opera. Perhaps the fairy Godmother, or Don Magnifico, of the opera world can make it come true, and soon.

Chris Mullins

Los Angeles Unified School District, Secondary Literacy

image=http://www.operatoday.com/content/Cenerentola.gif

image_description=Gioachino Rossini: La Cenerentola

product=yes

product_title=Gioachino Rossini: La Cenerentola

Jacopo Ferretti, libretto

product_by=Joyce DiDonato, Jose Manuel Zapata, Bruno Pratico, SWR Radio Orchestra Kaiserlautern; Prague Chamber Choir, Alberto Zedda (cond.)

product_id=Naxos 8.660191-92 [2CDs]

ALBRIGHT: Berlioz's Semi-Operas

In most of his large-scale works, Berlioz usually followed traditional forms and genres; in these two semi-operas, as the author calls them, experimentation with form and presentation are much more obvious, and this book assists the reader in following the literary and musical adaptations through history of these two texts by Shakespeare and Goethe, illustrating how Berlioz followed and built upon the composers and authors who set these two texts prior to his own compositional settings.

The author realizes that the term semi-opera refers to English opera of the later seventeenth century (according to Henry Purcell’s contemporary Roger North), but there just doesn’t seem to be another genre-term that comes closest to Berlioz’s style in these two compositions: drama that has been wrestled into music, through a strange array of disconnected scenes, where the composer has taken parts of the literary text that stimulated his creative thought and set them to music either vocally or as orchestral pieces. Berlioz, and the French public as well, had a hard time with Shakespearean and German drama. Berlioz was willing to experiment with the challenges of dramatically moving these texts into French theatre and opera, and as a result produced a kind of hybrid music drama that perhaps comes closer to the concept of Gesamtkunstwerk than even Wagner was able to do.

The book takes three chapters each to examine the histories and settings of these two texts. Romeo and Juliet is explored first, looking at Shakespeare’s background and inspiration for this text; the work is then discussed in relation to its expression from the time of Shakespeare up until the nineteenth century; finally the text is discussed in relation to Berlioz’s dramatic manifestation and musical composition. Goethe’s Faust is approached in the same way, from its creation, through the time period up until the nineteenth century, and then Berlioz’s realization of the text through music and drama.

This is a wonderful, concise, and compact discussion of two interesting and complex musical works of the Romantic period, exploring the historical and dramatic backgrounds of two of the more popular literary stories in human history. While written from the scholarly perspective, this book is easy to read and not overly technical in its presentation.

Dr. Brad Eden

University of Nevada, Las Vegas

image=http://www.operatoday.com/content/albright.jpg

image_description=Daniel Albright. Berlioz’s semi-operas

product=yes

product_title=Daniel Albright. Berlioz’s semi-operas: Romeo et Juliette and La damnation de Faust.

product_by=Rochester, N.Y.: University of Rochester Press, 2001. xiv, 144 pp. (Eastman studies in music series)

product_id= ISBN 1-58046-094-1

price=$75.00

product_url=http://astore.amazon.com/operatoday-20/detail/1580460941

“La Muette de Portici” : a small revolt in Ghent

The small lies are “Holland,” which in reality is not a country but the most Western and richest part of the Netherlands. Belgium didn’t exist in 1830. It was the southern part of the United Netherlands and was often called the Southern or Catholic Netherlands. Afterwards the name Belgium really came into its own and it is derived from the Latin “Belgica” which means “low or nether lands.” Therefore historical continuity was respected. And of course a lot of people in Belgium, now and then, call that revolution a separatist mutiny. But the big lie is the fact that the Brussels performance of La Muette didn’t cause the uprising.

The fifteen years between 1815 and 1830, when all the Netherlands were once more reunited after a separation of almost 250 years (remember Don Carlos), were not a very happy time due to a rather bad economic situation. The Dutch speaking part of the Southern Netherlands (nowadays Flanders) suffered a lot. Most people lived on small farms barely earning enough to survive and almost everybody produced home spun textiles for sale. With the collapse of the French empire that market was closed while on the other hand cheap British textile arrived in abundance. A lot of people fled to the cities where they started working at ever lower wages in textile plants that began to proliferate, thus eliminating all competition from home spun yard. Add to that several bad harvests and a restless Roman Catholic clergy that tirelessly preached all difficulties were God’s punishment. The Catholic Church in the South resisted Protestant equality and, in the process, incited the people against the King.

During the summer of 1830, there was one incident after another as poor people flocked to the towns to look for a job or simply to have something to eat. August was especially dangerous as the old and bad harvest had almost gone and the new one had not arrived yet and didn’t look too promising. At the Brussels Grote Markt and the Muntplein small clusters of unemployed people were causing troubles. But the bourgeoisie wasn’t very happy either. King William was interested in economics (a remarkable exception among most royal morons) and did much to stimulate the economy. But, he remained a 18th century despot. There was no liberty of press, of religion (the king controlled the appointment of bishops) or meeting. And then there was a lot of French intrigue as France had not digested the loss of the Southern Netherlands, which it had incorporated in 1794, and France detested a strong state on its northern frontier. On the 25th of August 1830 a performance of La Muette de Portici was going on at De Muntschouwburg (though at the time most called it Théatre de la Monnaie). Afterwards some spectators incited all those unemployed people hanging around the theatre to look for plunder in the houses of some collaborators of the king. The riots soon spilled over to other parts of the Southern Netherlands and even to Germany. People started smashing machines, which killed employment. The bourgeoisie didn’t like things running out of hand and started taking control of some cities. Things calmed down for a few weeks and everything would have calmed down as King William was prepared to compromise.

This, however, didn’t solve the problems of the working class as food became scarcer, as prices were steep and as bread prices rose due to a new harvest that was still partly in the fields. Unemployment rose even higher and now there went no day without incidents. The clinching event was the King’s decision not to wait for the arrival of the harvest but to send an army to calm things down by force. There was quite a battle in Brussels which was lost by the army, as the crown prince commanding it didn’t want to destroy one of his capitals (and moreover dreamed to usurp his father’s place and become king of the Southern Netherlands). The army fled and all over the South the administration collapsed.

Though there was never a general vote, it is clear that most people wanted to destroy the Union and preferred returning to the old well-known Southern Netherlands, though under the name of Belgium. Of course this was no longer the old confederation that had governed itself in the 17th and 18th century, but a strongly centralized state in the French mould. The young state came into the hands of a French speaking bourgoisie that found its strength in the French speaking part (Wallonia) where the industrial revolution was already well on its way. Agrarian Flanders was very poor and was discriminated against in all possible ways, economically and culturally — Justice was often handed out in French only and Flemings who could only speak Dutch were sometimes not allowed to defend themselves in their own language. That discrimination only ended in the 1960s when the multinationals once more made Flanders the far richest part of the country and some laws made an end to the preponderance of French over Dutch. Nevertheless some Flemings have never accepted the breaking up of the Dutch speaking peoples and they still hate every Belgian celebration even when it is an opera.

During the first half of the 19th century many people still knew what had really happened and there was much bitterness towards the bourgoisie. They had taken power in their hands and had reserved the vote for exactly 0.5% of the population. Almost nobody who died during the successful revolt would have gotten the vote had he lived. The new masters didn’t want to be reminded of the true origins of the revolt and they much preferred and encouraged the myth that the singing of the duet “Amour sacré de la patrie” made the revolution happen. After all, opera was their favored art and for them it made a far more interesting story than the revolt of unemployed people. The world of opera of course helped to propagate the myth. The last performances of the opera in this country were 100 years later in 1930 at De Munt with Fernand Ansseau and Ernest Tilkin-Servais. During the 22 performances the audience always rose at the singing of “Amour sacré”. Fifty years later in 1980 there would be a new performance in Brussels with José van Dam as Pietro. Everything went smoothly till the day of the performance. Then it became known that hundreds of radical Flemings had not forgotten the “separatist mutiny” and intended to demonstrate during the performance. It was cancelled.

And so to 2005. In Ghent there is a private organization run by one man, John Boeren, which performs operas no longer in the repertory as directors and general managers hate operas they cannot kill with an “innovative concept”. Boeren receives almost no subsidies and when somebody suggested that he could get some money at last by inserting a performance as a kind of celebration for 175 year of Belgium he gladly accepted the idea. Originally he wanted to perform Manon but the idea of getting a meager 2.500 Euros was enough to change his mind. That’s when this writer starts to play a role. I got an anonymous mail telling me that once more some radical Flemings were going to kill that Muette. I have a column in the biggest radical Flemish weekly — Yes, I too much prefer an independent Flemish republic — and I wondered why radical Flemings share the same stupid myth with the most backward followers of unitary Belgium. Moreover I told them to demonstrate before and after the performance but to leave the opera itself in peace, as I don’t want to be reminded of the thirties when some people in Germany disturbed opera performances conducted by Bruno Walter. The radicals were almost hysterical and deluged my (and their) weekly with mail but as their plans were now clear for everybody to see they compromised. They had bought 50 tickets and they made an agreement with the police, the mayor and John Boeren that they would interrupt for 5 minutes exactly and then leave the theatre. As could be expected they awaited the start of “Amour sacré” and then sang the Flemish national hymn, cried slogans in favor of the United Netherlands once more and left exactly as they had promised. Everyone was happy: the spectators, who remained very calm, were glad that they didn’t miss a single note; the demonstrators were on television and John Boeren for the first time got formidable free publicity (and nothing else as he didn’t receive a single promised Euro subsidy).

And, oh yes, there was a performance. La Muette was not given in the opera but in the concert auditorium of the Bijloke, a magnificent medieval abbey in the heart of Ghent. The auditorium is very well apt for a lieder recital or a chamber orchestra but in the rather small space a real orchestra sounds somewhat too noisy with the brass section especially drowning out everybody else. A pity as Jean Pierre Haeck, a conductor from Liège, really likes this repertory and succeeds in breathing life in it. The amateur chorus moreover sang as good as any professional body. John Boeren can put 30,000 Euro down for orchestra, chorus, singers, box office and hire of the auditorium. Still he succeeded well. Tenor Tiemin Wang (a member of the De Munt chorus) sang with style and a hint of steel that reminded one here and there of Tony Poncet. Young Flemish tenor Ludwig van Gyseghem has some promising material and was a very fresh voiced Alphonse who has only to strengthen his high register. Best was Liège soprano Amaryllis Grégoire: a good supple voice with excellent diction, clear bell-like high notes. Only baritone Patrick Delcour (usually a comprimario at the Liège opera) was a little too rough as Pietro. So there is quite some life left in the old war horse and many an opera house could do worse than produce La Muette de Portici. I’m sure it will make an even more stronger impression on the boards and I even put forward the heresy that it wouldn’t suffer from some updating in a brilliant director’s concept.

Jan Neckers

Keerbergen, Flanders

image=http://www.operatoday.com/content/Auber.jpg

image_description=Daniel Francois Esprit Auber

October 26, 2005

Great Operatic Arias, Vol. 17 — Christine Brewer

The singer Christine Brewer and the music deserve that, and not the often awkward translations and occasionally sub-par conducting and recording supplied by producer Chandos for the Moores Foundation’s English series [Chandos 3127].

Let me get my own bias, if that’s the term, out of the way up front: I find it hard to enjoy German, French or other languages translated into English for operatic performance. I’ll never forget an English National Opera production in the 1970s, of the French Manon with Valerie Masterson and Alberto Remedios, which should have been stunning, but was reduced to near-Gilbert and Sullivan in the English vernacular. But, hark! All is not lost, for just as soon as Brewer has delivered an impressive, if Englished, “Ocean Thou Mighty Monster” (Weber) on this disc, than she turns to Arthur Sullivan’s cantata, The Golden Legend for the big soprano/choral scene, “The Night is Calm and Cloudless” – a big dramatic scene in best Victorian style – that proves quite effective in its native English. I rest my case. Native lingo is best, for the language is part of the music.

With that caveat, how does La Brewer do with her big dramatic pieces mixed in with a few show tunes in this new arias disc? Swimmingly in the classical numbers, a bit less idiomatically in the translated operetta pieces by Lehar and Kalman, but fine in tunes of Richard Rodgers and Bob Merrill. Where there are problems, they seem to come from David Parry and the Philharmonia Orchestra and a choir. The lead-in to Countess Maritza’s entrance aria is a real bog – not only slow, but dragged down tonally and out of synch between orchestra and a slightly rough chorus. Better rehearsed, put back into German and speeded up it would be just fine. Brewer’s mellow low and mid-voice rendition of Rodger’s immortal “You’ll Never Walk Alone” is big league; it may well be remembered as a touchstone performance. Rossini’s Stabat Mater is dropped into the middle of these light songs, and the “Inflammatus” rings with resounding soprano tones just in case we’ve forgotten Brewer is one of the most luxurious big voices of our time. Three out of a dozen selections are in their original English, and they are entirely comfortable. The juicy Kalman operetta aria “Meine lippen sie kussen so heiss,” here “On my lips ev’ry kiss is like wine” (see what I mean?), is sung elegantly, if without the lilt and flirt of the German text. Beethoven’s concert aria, “Ah Perfido,” to my ear the best performance on this CD, is sandwiched between Lehar and Bob Merrill (his lovely Lili’s song ‘Mira’ from Carnival) creating a peculiar ambience if one listens straight through the disc, which is not recommended. But the Beethoven is superb, sung with much feeling and poise, and with ravishing tone, Brewer at her best. But who set the order of these selections? It’s wiser to make one’s own.

Finally, I do have to carp a little about the sonics: Heaven knows Brewer needs no help with pitch or amplitude. But the engineers have fiddled with the position of the voice, often too close, and have added resonance, which can sometimes create a ragged release or blurred detail, as in the smudged, rushed orchestral opening in Elisabeth’s Act II aria from Tannhauser, and the occasional forte high note can blast. Brewer sings “Mira – Can you imagine that,” so sweetly and simply, it is one of her finest numbers; but here it is set in a resonance too big and imposing. Even so: yum!

Most of all I wish conductor David Parry had worked his musical forces into a better fused whole, and achieved more graceful and consistent tempos. At times he is too cautious and can seem to hold back the soloist.

In sum: a mixed blessing, but worth its price due to the many beauties of Christine Brewer and quality of the music she sings. This is a good documentation of her distinguished talents, caught in top form over three days in March 2005.

J. A. Van Sant

Santa Fe, New Mexico

image=http://www.operatoday.com/content/CHAN%203127.jpg

image_description=Great Operatic Arias, Vol. 17 — Christine Brewer

product=yes

product_title=Great Operatic Arias, Vol. 17 — Christine Brewer

product_by=Christine Brewer, soprano, Philharmonia Orchestra, David Parry (cond.)

product_id=Chandos CHAN 3127 [CD]

BACH: Cantatas, vol. 18

This volume contains 6 cantatas, 3 each for the third and fourth Sundays after Easter. Despite the unimaginable number of difficulties in coordinating the series (differing pitch of various organs, very limited rehearsal time, changes in personnel, travel arrangements for some 40 musicians and a crew of other people) that such a project entails, this disc ranks in quality with the finest in modern Baroque performances.

From the titles of the cantatas for Jubilate Sunday, the first group of three, we might gather that the works provide a lugubrious mood: Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen (Weeping, Wailing, Fretting, Fearing), BWV 12; Ihr werdet weinen und heulen (Ye shall weep and lament), BWV 103; and Wir müssen durch viel Trübsal in das Reich Gottes eingehen (We must through much tribulation enter into the kingdom of God), BWV 146. (As the reader may note, Richard Stokes’s English translations, provided in the accompanying booklet, can be quite inelegant, even though they were not devised to match the German text syllable for syllable so that they could be sung without altering the music.)

The mournful feeling is reflected in the first two numbers of BWV 12: a sinfonia with a slow, plaintive, and beautifully played oboe solo (are there ever slow, non-plaintive oboe solos?), followed by a choral movement that Bach later adapted for the Crucifixus of the Mass in B minor to portray the crucifixion and death of Jesus on the cross. Gardiner terms each of the first four words “a heart-rending sob” that may be thought of in connection with the “four hammer blows nailing Christ’s flesh to the wood of the cross.” The image takes on credibility when one realizes that the corresponding syllables in the Mass are Cru-ci-fi-xus, He was crucified.

The words of the alto recitative that follows, Wir müssen durch viel Trübsal from Acts 14:22, would later find their way into the title and opening chorus of BWV 146. The mood brightens considerably in successive arias for bass and tenor, both with a trumpet obbligato playing the melody of the Jesu, meine Freude (Jesus, my delight), and the closing chorale is positively joyful: Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan (What God does is well done).

The Cantata BWV 103 follows a somewhat similar trajectory: weeping, lamentation, and transgression are the subjects of the first three movements, although Bach plays a little trick on listeners. The opening orchestral introduction sounds quite jolly, but when the solo voices enter, we realize that “the festive instrumental theme represents not the disciples’ joy at Christ’s resurrection but the skeptics’ riotous laughter at their discomfort” (Gardiner). Then an alto recitative begins to turn things around, trusting “that my sadness shall be turned into joy”; a rapturous tenor aria declares that Jesus will reappear; and the happy and uplifting chorale at the end of the work is a verse from Was mein Gott will, das g’scheh’ allzeit (What my God wants, that will always happen), stating that brief pain shall turn to joy.

Finally, in the third cantata for Jubilate, BWV 146, we hear an opening sinfonia that sounds suspiciously like the first movement of the D minor Harpsichord Concerto (BWV 1052a) with an organ playing the solo part. Well, that is exactly what it is, and the opening chorus that follows, Weinen, Klagen, equals the second movement of the concerto with added choral parts. The now-familiar turn to happier matters occurs more gradually through the middle movements, and the cantata ends with a verse from the chorale Werde munter, mein Gemüte (Become enlivened, my spirit).

Disc 2 of this set includes three works composed for Cantate Sunday, the fourth Sunday after Easter, including Wo gehest du hin? (Whither goest thou), BWV 166; Es ist euch gut, daß ich hingehe (It is expedient[!] for you that I go away), BWV 108; and Sei Lob und Ehr dem höchsten Gut (Give laud and praise to the highest good), BWV 117. I will let the listener enjoy the disc without comment, except to point out a single cut: the dramatic and sensitive performance of the closing chorale of BWV 166, Wer weiß, wie nahe mir mein Ende (Who knows how near my end is). It is Gardiner and his group at their very best.

Michael Ochs

image=http://www.operatoday.com/content/gardiner_bach_18.gif

image_description=J. S. Bach: Cantatas for the Third and Fourth Sundays after Easter

product=yes

product_title=J. S. Bach: Cantatas for the Third and Fourth Sundays after Easter

product_by=Brigitte Geller, William Towers, Mark Padmore, Julian Clarkson, Robin Tyson, James Gilchrist, Stephen Varcoe, Monteverdi Choir, English Baroque Soloists, John Eliot Gardiner (cond.)

product_id=Soli Deo Gloria SDG 107 [2CDs]

SZYMANOWSKI: Piano Music

Anderszewski’s performances of these works are compelling for a variety of reasons, not the least of which is his fine sense of style the composer’s style that he conveys so clearly. This is an important contribution that merits attention to both the performer and the literature he interprets so well.

For some Karol Szymanowski (1882-1937) is the proverbial watershed between late nineteenth-century Romanticism and twentieth-century modernism, especially when it comes to musical developments in Poland. Szymanowski composed music for piano throughout his career, and the three pieces that Piotr Anderszewski recorded on this collection emerge from a three-year period between 1915 and 1917, and they look both backward and forward in the composer’s oeuvre.

Some of Szymanowski’s earlier compositions use traditional forms, albeit imbued with his unique content, and only later did he take inspiration from program music and impressionism. Along these lines, while the Third Piano Sonata is traditional in structure, the other two pieces contain extramusical elements that suggest images rather reach beyond music, with references to women from Homer’s Odyssey in Métopes and fictional personas like Sheherazade, Tristan, and Don Juan in Masques.

As character pieces, each of the Masques possesses an individuality that belongs to the descriptive title. The playfulness of the second piece, “Tantris le bouffon” (“Tantris [Tristan] the clown”) calls to mind the legendary episodes when Tristan reversed the syllables of his name and disguised himself as a clown so that he could return to King Mark’s court to catch a glimpse of Isolde. Not a literal retelling of the Tristan story, the title offers a clue to interpreting the music, which resembles a Scherzo in style and proportion – it is half the length of the more serious “Schéhérazade” that precedes it.

The image of Schéhérazade evokes various characterizations, from the romantic depiction of the storyteller’s persona by Rimsky-Korsakov in his four-movement symphonic poem to Ravel’s extended setting for voice and piano that subtly evokes the exotic – the other – and our attraction to it. In his “Schéhérazade” Szymanowski uses the solo piano to explore those exotic aspects of the character by developing various motifs and fragments throughout the piece. Starting with relatively brief elements, the composer arrives at increasingly longer themes that are the subjective, in turn, of further development in the central section of the piece. Once he has given those ideas shape, he allows the music to dissolve into shorter fragments that call to mind the way the piece began.

The music of “Schéhérazade” has a parallel in the last of his Masques, the piece entitled “Sérénade de Don Juan.” Again, this calls to mind the various depictions of the Don and, overtly, suggests the strumming of a guitar. This approach frames his rondo-like form of the pieces that returns to the same theme. If a programmatic association must be given, it is the insistent return to the same theme, which can be likened to Don Juan’s incorrigible nature. More than program music, the “Sérénade” demands a solid interpretation, which Anderszewski provides in his fine performance this piece and the others in the set.

Similarly evocative, the Métopes also consist of three pieces, each referring to women in The Odyssey. The architectural term “métope” refers to the spaces between the triglyphs on a Doric frieze and implies something significant in the linkages. While Szymanowski is nowhere explicit about his use of the term, he offers points of departure in the descriptive titles for the three pieces in this set. The first, “L’île des sirenes” evokes French impressionism with its use of whole-tone sonorities and goes even further with passages that are polytonal. Its subtlety and ambiguity makes the piece attractive; and it not only reflects some of the music of Debussy, but also looks forward to some stylistic traits associated with Messiaen. In “Calypso” Szymanowski makes use of non-traditional tonality, but instead of the short ideas that permeate “L’île des sirenes” he uses longer themes in “Calypso” that recur as refrains. Of the three pieces, “Nausicaa” offers a clearer sense of form and less dissonant idiom. Nevertheless, Szymanowski makes use of colorful dissonances within the structure of this satisfying conclusion to Métopes.

Szymanowski’s Piano Sonata no. 3, op. 36, is a more abstract work in four movements. It contains no programmatic association, and is, instead, more formal in orientation. It is the latest of the three works on this CD, and in it Szymanowski evokes a kind of timeless modernism. The first movement is a traditional sonata that makes use of colorfully dissonant sonorities and extremes of register, while the second is a slow movement with continually full sonorities at various dynamic levels that require a sensitive performer to execute well. The third movement is essentially a Scherzo that puts other demands on the player with its mercurial themes and repeated-note figures. As a final movement, Szymanowski creates a modernist fugue that forms a satisfying conclusion to the Sonata. At times the music evokes the kind of sardonic style that would be later associated with Shostakovich. It is immediately engaging, and those unfamiliar with Szymanowski’s music may wish to start with this movement, which is one of the composer’s finest pieces.

As with his style in general, the musical idiom that Szymanowski uses for all three of the works included on this CD is rooted in tonality, but his mode of expression involves expressive dissonances, ostinatos, and other devices associated with early twentieth-century modernism. Szymanowski did not endorse any single technique in his music, but used various elements to create an individual idiom that reflects, at times, some aspects of French impressionism. At times, though, his use of percussive dissonances suggests some aspects of eastern European composers, like Béla Bartók. Formally, Szymanowski is rooted and tradition, and while he may blur the sectional divisions that would have been less ambiguous for a composer of the previous generation, the overall structure is nonetheless traditional. As innovative as it can be, Szymanowski’s music nonetheless accessible, albeit demanding for both the listener and performer.

In this recording the young Polish music Piotr Anderszewski (b. 1969) gives a convincing reading of all three pieces, which calls to mind the incisive style found in his other performances of more traditional repertoire, like Beethoven’s Diabelli Variations and selected repertoire by Chopin. For those unfamiliar with Anderszewski’s playing, his recent recording of a selection of Chopin’s ballades, mazurkas, and polonaises (Virgin Classics CD 7243-5-45620-2) has much to recommend, including an incisive reading of the well-know Polonaise no. 6 in A-flat major, op. 53. The clarity that Anderszewski commands in the performance of this “Polonaise héroique” contributes to his effective interpretation of later recording of Szymanowski’s music. Yet his fascinating interpretation of Szymanowski’s stands apart, for its masterful approach to literate that clearly deserves to be heard more often in recitals. With this recording of Szymanowski’s music, Anderszewski has shown himself to be a performer who has much to offer.

James L. Zychowicz

Madison, Wisconsin

image=http://www.operatoday.com/content/Szymanowski_piano.gif

image_description=Szymanowski: Piano Music

product=yes

product_title=Karol Szymanowski: Masques, Op.34; Piano Sonata No.3, Op.36; Métopes, Op.29.

product_by=Piotr Anderszewski, piano.

product_id=Virgin Classics 5457302 [CD]

Has the fat lady sung for Italian opera?

By Peter Popham in Rome [The Independent, 26 October 2005]

By Peter Popham in Rome [The Independent, 26 October 2005]

Italy is the home of opera so it may come as some surprise that its demise is being predicted.

Curtains for La Scala? The culture minister, Rocco Buttiglione, has warned of the possible "death of opera" as the nation's 13 deeply indebted opera houses try to find ways to survive a 30 per cent cut in government subsidies, announced in the new budget.

Wagner's `Ring' Features Eschenbach, Singing Zombies in Paris

[Photo: M.N. Robert]

By Jorg von Uthmann [Bloomberg.com, 26 October 2005]

Richard Wagner hated the Parisians because they had humiliated him in 1861 with noisy demonstrations against "Tannhauser.'' His opera had to be withdrawn after three performances.

Since then, the Parisians have made up for their poor behavior. While the Opera Bastille is reviving last year's production of ``Tristan und Isolde,'' the Theatre du Chatelet has just started a new "Ring des Nibelungen'' — only 11 years after its last production of the tetralogy.

The Mines of Sulphur, New York City Opera

By Martin Bernheimer [Financial Times, 26 October 2005]

By Martin Bernheimer [Financial Times, 26 October 2005]

The stage is bleak, shadowy, scary. The orchestral writing, quite massive, is dissonant, descriptive, percussive. The vocal lines are wide-ranging and awkward yet poignant. The plot examines the wages of murder, retribution and guilt.

When a Sex Slave Makes Her Escape, Revenge Is in the Supernatural Air

By ALLAN KOZINN [NY Times, 25 October 2005]

By ALLAN KOZINN [NY Times, 25 October 2005]

The New York City Opera, sensibly enough, regards its large repertory of standard works in efficient, mostly traditional stagings as its box-office bread and butter. But if you think back over the company's productions of the last 15 years, contemporary works - Zimmermann's "Soldaten," Hindemith's "Mathis der Maler," Carlisle Floyd's "Of Mice and Men" and Hugo Weisgall's "Esther" among them - have been the clear highlights. They have typically had short runs and they rarely return, but they are the soul of this company.

October 25, 2005

Loud and clear — Yvonne Kenny wants to break down barriers between the "amplified" generation and opera lovers

By Robin Usher [The Age, 26 October 2005]

By Robin Usher [The Age, 26 October 2005]

There is something remarkable about the voice of soprano Yvonne Kenny, Australia's best-selling classical artist and a favourite with live audiences. But she believes the way to ensure that people keep going to classical concerts is to break down barriers between the art form and the younger generation.

Opera babes — Glyndebourne is reaching out to twentysomethings with its new operatic thriller Tangier Tattoo. What did post-punk rockers the Suffrajets make of it?

By Tom Service [The Guardian, 25 October 2005]

By Tom Service [The Guardian, 25 October 2005]

Glyndebourne Touring Opera had a big idea for this autumn: the world premiere of an opera for what they describe as the "lost generation" of 18- to 30-year-olds. "Lost", that is, to the opera house, since twentysomethings make up only a tiny percentage of the average operatic crowd, which is still dominated by a greying, elderly population. This is the third youth opera that Glyndebourne have put on in the past few years, after Misper (written specifically for young teenagers), and Zoë (an opera on cloning), for sixth-formers. They've used the same creative team of writer Stephen Plaice and composer John Lunn for the new piece, Tangier Tattoo. It is billed not as a boring old "opera" but an "operatic thriller", and it's a tale of drugs, sex, terrorism and skin decoration, subjects that emerged from focus groups as the most likely to turn on the target audience.

Before being put to death, Norma would like to say a few words -- and sing her heart out

Steven Winn, [SF Chronicle, 25 October 2005]

Steven Winn, [SF Chronicle, 25 October 2005]

Moments after the heroine's hushed confession, in the final scene of "Norma" at the War Memorial Opera House, the chorus murmurs a heartsick response: "Our blood runs cold." The audience feels it right along with them. Here, in a San Francisco Opera production that has some substantial liabilities to overcome, the power of Bellini's 1831 masterpiece shines through in all its ravishing, blood-chilling complexity.

An Opera Without Melodies

BY FRED KIRSHNIT [NY Sun, 25 October 2005]

BY FRED KIRSHNIT [NY Sun, 25 October 2005]

Imagine that Shakespeare had titled that play "The Murder of Gonzago" rather than "Hamlet" and you will have a good notion of the conceit of Richard Rodney Bennett's "The Mines of Sulphur," which had its City Opera premiere on Sunday afternoon.

Opera Company unmasks a 'Ballo' in excellent voice

By David Patrick Stearns [Philadelphia Inquirer, 25 October 2005]

By David Patrick Stearns [Philadelphia Inquirer, 25 October 2005]

The opera gods giveth and taketh singers with merciless capriciousness. And certainly they tooketh the Opera Company of Philadelphia's last season of well-laid plans demolished by cancellations. Yet at Sunday's opening production of the new season, Verdi's Un Ballo in Maschera arrived with the gods rewarding us for our patience.

October 24, 2005

PUCCINI: Tosca

Principal Characters:

| Floria Tosca, a famous singer | Soprano |

| Mario Cavaradossi, painter | Tenor |

| Il Barone Scarpia, Chief of Police | Baritone |

| Cesar Angelotti, a political prisoner | Bass |

| Il Sagrestano (the sacristan) | Baritone |

| Spoletta, a police agent | Tenor |

| Sciarrone, a gendarme | Bass |

| Un Carceriere (a jailer) | Bass |

| Un Pastore (a shepherd) | Boy soprano |

Time and Place

June 1800, Rome

Summary

Act One

Setting: Inside the Church of Sant'Andrea della Valle, Rome.

Angelotti, a political prisoner, enters furtively, having just escaped from the Castel Sant'Angelo through the help of his sister, the Marchesa Attavanti, who has left him some clothes in the church and the key to the Attavanti Chapel, where he can hide and disguise himself. When Angelotti is hidden, the painter Mario Cavaradossi comes in to resume work on a Maria Maddalena. The sacristan points out a resemblance between the Maria Maddalena and a strange lady who has been coming to the church frequently of late (the Marchesa). Mario contemplates the harmony of the stranger's beauty with that of his beloved, Tosca. Angelotti reappears and recognizes his old friend, Mario. Mario promises to help, but they are interrupted by the appearance of Tosca. Angelotti hides, which leads Tosca to become jealously suspicious. Mario allays her suspicions they agree to meet that evening. After Tosca leaves, Angelotti reemerges and Mario takes him to his villa outside the city.

The sacristan returns to announce the defeat of Napoleon but finds Mario has left. Choristers and acolytes prepare the Te Deum to celebrate the victory of the royalists; however, they are silenced when Scarpia enters. He has tracked Angelotti to the church and Mario's lunch basket is found in the chapel. Mario now becomes the target of his suspicions. Using the Marchesa's fan to arouse Tosca's jealousy, she flees the church and is followed by Scarpia's men. Scarpia relishes the thought of having Mario executed and possessing Tosca.

Act Two

Setting: Scarpia's apartments in the Palazzo Farnese.

As the Queen of Naples celebrates the victory in another part of the building, Spoletta arrives to report that Angelotti could not be found at Mario's villa. Mario has been brought in for questioning, but he stands silent. Tosca arrives. Mario urges her not to say anything. She nevertheless reveals Angelotti's whereabouts as Mario is being tortured. Mario rebukes her; however, he is overjoyed when Sciarrone arrives to inform Scarpia that Napoleon has won the battle at Marengo. Scarpia orders Mario to be executed at dawn. Tosca pleas for mercy. Spoletta returns with news that Angelotti has killed himself, rather than be captured. Scarpia offers to hold a mock execution of Mario in exchange for Tosca's love. She agrees. As he writes out the safe-conduct, Tosca grabs a knife on the table. When Scarpia approaches to claim his prize, she stabs him.

Act Three

Setting: Dawn atop the Castel Sant'Angelo.

While a shepherd sings in the distance, Mario is brought up to his place of execution. Alone he contemplates Tosca and his life. Tosca arrives withnews of the mock execution. She admits that she has killed Scarpia. The execution is ordered. Mario falls. Tosca approaches and urges him to rise only to find that he is dead. Spoletta then rushes in to arrest her for the murder of Scarpia. Tosca jumps from the parapet to her death.

Click here for the complete libretto.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/content/tosca-poster2.gif

image_description=Tosca

audio=yes

first_audio_name=Giacomo Puccini: Tosca

first_audio_link=http://www.operatoday.com/Tosca_1.wax

product=yes

product_title=Giacomo Puccini: Tosca

product_by=Maria Callas, Giuseppe di Stefano, Tito Gobbi, Coro e Orchestra del Teatro alla Scala, Milano, Victor de Sabata (cond.)

King Arthur - the first musical?

Flimm’s magical and creative stage direction seldom flags, and Harnoncourt’s Concentus Musicus Wien drives the whole mad, not to say occasionally maddening, pantechnicon along at a great pace and with admirable musical sensibility.

The pain came with equal regularity however. An interesting point about these last great flowerings of young Henry Purcell’s genius, so soon to be snuffed out, is that they were almost an anachronism when they first reached the stage of the Queens Theatre, Dorset Garden, London in 1691. Italian opera was approaching as if on a flood tide. Today it is difficult for an audience raised on either that later opera seria or mainstream romantic opera to grasp either the idiom of English music theatre in the 1690s or accept its artistic context - such as might be gleaned from a quote in the Gentleman’s Journal of 1692 “…experience hath taught us that our English genius will not relish that perpetual Singing,” Those said Gentlemen preferred what we might call today “mixed media” with plots that were not only true to life but sported humour, slapstick and sensational effects. And this Salzburg production, in the final analysis, whilst trying to achieve relevance and an understandable context by updating this template from the 1690’s, is let down by artistic incoherence and muddle. The fun, the spirit and the comedy of what Harnoncourt has described as the “first musical in history” doesn’t quite make up for some pretty dire interpretative decisions.

So if not an “opera” at all, then or now, what is it? It’s a play, with words by Dryden, which has musical tableaux which intersperse the main blocks of story-telling dialogue. The drama, acted and spoken by professional actors, tells the story of enemy kings Arthur and Oswald, fighting for English power and the heart of a princess, Emmeline, who happens to be blind. Each is supported by their own “magical helpers” - Merlin (a slightly ineffectual English dandy) and Grimbald (a most unpleasant piece of work) - and accompanying spirits. There is no doubt who are the “goodies” and “baddies” and which side this jingoistic libretto takes. It also just so happens that the music that was written to accompany the piece at the theatre was some of the best truly indigenous English song writing ever to bloom on a London stage, even to this day. And as in Purcell’s time, both the actors and singers are on stage together and often “duplicate” each other with matching costumes - an idea that one soon assimilates without too much trouble, although the camera close ups of the DVD obviously make this deliberate deceit entirely transparent.

The story is a gift for any creative director with the full panoply of 21st century stage effects at his disposal, and Flimm makes admirable use of the unique setting: the Summer Riding School in Salzburg, with its baroque form and intriguing balustraded arcades, built in 1693. The excellent orchestra is housed in a sunken area around which the stage continues, allowing the actors and singers to occasionally encompass the musicians and, from time to time, even draw them and their conductor into proceedings. This allows nice little comic business: the rather august head of Nikolaus Harnoncourt being carefully wrapped in a woolly bobble cap against the cold of the Frost Scene; a terrified fairy seeks shelter amongst the bassoons… and so on. Video screens in the “sky”, flying lines for the fairy spirits, trap-doors for the almost Wagnerian evil-doers on the Saxon side - it’s all there, and you’d have to be a very miserable person not to respond with a smile, at least once per scene.

However, as was reported at the time of the stage premier, the successes must be weighed against some unfortunate decisions. Dryden’s story may not be exactly great drama - it’s been described as “tub-thumpingly patriotic” and you’d be hard pushed to deny that. But, and it’s a big but, the language he used to do the tub-thumping was elegant, witty and often beautiful. Here, presumably for the sake of Salzburg success, all the English drama is translated into German, with almost entirely German or Austrian actors. What was wit with a lighter touch becomes heavily obvious; what was English seaside-style slapstick becomes Bavarian bier-keller. Vowel-curdling diction in mock-mittel-european-horror-flick style does Dryden no favours, and it is with huge relief that one hears the first melodic lines of English when the singers (excellent in name, if uneven in performance on this showing) take the stage.

One is reminded of a kind of “beauty and the beast” scenario. On the DVD, of course, one has the convenience of subtitles - so at least the viewer at home can have the story explained in English, or whichever language is preferred. Not that this helps particularly with all the local in-jokes and modern Austro/German political references which attempt to make relevant some of the original humour - always high risk for an internationally-released production.

Yet, happily, it is the music of Purcell that saves the day every time - tune after tune delights the ear and kindles memories from a hundred earlier hearings in different, incomplete contexts: “First Act Tune”, “How blest are shepherds”, the “Chaconne”, “’Tis Love” and “Trumpet Tune”, the list goes on and on. To at last hear them in the way that London audiences did in 1691 is a treat indeed.

The voices are certainly starry: Barbara Bonney, Michael Shade, Isabel Rey, Oliver Widmer and Birgit Remmert and you have to applaud the way they throw themselves (sometimes literally) into the story even if some are hard pressed to produce their best sounds in some difficult situations and eccentric costumes. The sight of a well-built Michael Shade throwing himself around the stage, stand- mic clasped to mouth, legs akimbo, in a hilarious spoof on an ageing rocker howling out “Your hay, it’s mowed” in the form of a torch song to his adoring fans, won’t be easily forgotten.

Less successful was Bonney’s rendition of the lovely, seraphic “Fairest Isle, all Isles Excelling” towards the end of the performance - not approaching the silvery perfection of her CD recording and somewhat rushed and uncomfortable in execution. The famous “Frost Scene” was played for humour with a chorus of neatly-choreographed penguins (what else?) in support, even if Oliver Widmer’s rather clunky baritone made heavy arctic weather of the famously-extreme stuttering notes.