January 30, 2007

"Colombe" reprend son envol à l'Opéra de Marseille

[Le Monde, 29 January 2007]

[Le Monde, 29 January 2007]

Pour la troisième fois de sa carrière de directrice d'opéra, Renée Auphan fait la lumière sur l'un des "trous noirs" de la musique de la seconde partie du XXe siècle : l'oeuvre lyrique de Jean-Michel Damase (né en 1928). Après avoir chanté Madame de... (1970), Eurydice (1972), et L'Héritière (1974), Renée Auphan, qui fut une artiste lyrique d'envergure, aura monté Madame de... au Grand Théâtre de Genève, puis, à l'Opéra de Marseille, dont elle est l'actuelle directrice, L'Héritière (Le Monde du 13 mai 2004) et, cette saison, Colombe (1961), d'après la pièce de Jean Anouilh.

Michele Pertusi

ANDREW CLARK [Financial Times, 29 January 2007]

ANDREW CLARK [Financial Times, 29 January 2007]

There are a good few opera singers who make fine recitalists. There are many more who feel naked when addressing an audience without a costume. Perhaps that is why we have had to wait until now to hear Michele Pertusi in recital. He was an admired operatic bass in the 1980s and 1990s, appearing mainly in Rossini and Mozart, at Covent Garden and other leading European houses. But younger singers have usurped his signature roles, and judging by this performance in the Rosenblatt series at St John’s, Smith Square, he is a reluctant recitalist.

Marilyn Horne Puts Her Protégés on Parade in Song

By ANNE MIDGETTE [NY Times, 29 January 2007]

By ANNE MIDGETTE [NY Times, 29 January 2007]

The standing ovation came before a note of music had been sung. The Marilyn Horne Foundation’s annual gala recital is supposed to focus on song, but it also focuses on Marilyn Horne. Looking radiant in gold lace, apparently undaunted by a year’s struggle with cancer, she played host to Friday evening’s event at Zankel Hall, a night after giving a master class there, with every bit of her star flair. And at her first entrance the audience stood, with applause and shouts of “Brava,” to greet her.

In Opera’s Famous Pair of One-Acts, Tenor Doubles His Workload

By BERNARD HOLLAND [NY Times, 29 January 2007]

By BERNARD HOLLAND [NY Times, 29 January 2007]

The traveling sideshow of “Pagliacci” added a strongman act to its clowns, acrobats and derailed theatrical entertainments on Friday night. Salvatore Licitra was scheduled to sing Leoncavallo’s Canio at the Metropolitan Opera, while Frank Porretta would be Mascagni’s Turiddu in “Cavalleria Rusticana.” On Thursday Mr. Porretta reported in sick. Rather than let a cover singer be called for, Mr. Licitra said he would sing both operas.

January 28, 2007

Händel in Mozarts Gewand, welche Herausforderung!

VON WALTER DOBNER [Die Presse, 29 January 2007]

VON WALTER DOBNER [Die Presse, 29 January 2007]

Zur Eröffnung der Salzburger Mozartwoche enttäuschte Adam Fischer mit dem "Messias". Überzeugen konnte hingegen der Schweizer Komponist Jörg Widman.

Dresscode für die Opernbesucher

Von Kai Luehrs-Kaiser [Die Welt, 29 January 2007]

Von Kai Luehrs-Kaiser [Die Welt, 29 January 2007]

Die Mailänder Scala hat einen Aufruf für korrekte Kleidung erlassen - und druckt ihn auf der Rückseite der Eintrittskarten. Das Opernhaus ersucht um Kleidung, "die im Einklang mit dem guten Ton des Theaters steht". Die Maßnahme ist ein Hilfeschrei.

The Elixir of Love

Richard Morrison at The Grand, Leeds [Times Online, 29 January 2007]

Richard Morrison at The Grand, Leeds [Times Online, 29 January 2007]

Transposing 19th-century operas to the glitzy dolce vita world of 1950s Italy has become something of a cliché. You can see why. The stage can be flooded with light. Those curvy frocks and high heels flatter the fuller-figured soprano. And the more glamorous of the male chorus can whizz round on Vespa scooters, looking chic in shades.

Rodolfo and Mimi Soar Again

By ANTHONY TOMMASINI [NY Times, 26 January 2007]

By ANTHONY TOMMASINI [NY Times, 26 January 2007]

Not many tenors these days excel in the full-bodied, lyric Puccini and Verdi repertory once owned by the likes of Carlo Bergonzi, Giuseppe Di Stefano and Luciano Pavarotti. The closest we have may be the Italian tenor Marcello Giordani, who took over the role of Rodolfo on Wednesday night for the first of four final performances in the Metropolitan Opera’s current revival of Puccini’s “Bohème.” His Mimi was the Chilean soprano Cristina Gallardo-Domâs, which united the stars of the Met’s acclaimed Anthony Minghella production of Puccini’s “Madama Butterfly.”

PUCCINI: La Bohème

First Performance: 1 February 1896. Teatro Regio, Turin

| Principal Characters: | |

| Rodolfo, a musician | Tenor |

| Schaunard, a musician | Baritone |

| Benoit, a landlord | Bass |

| Mimi, a maker of artificial flowers | Soprano |

| Marcello, a painter | Baritone |

| Colline, a philosopher | Bass |

| Alcindoro, a state councilor | Bass |

| Musetta | Soprano |

| A Custom-House Sergeant | Bass |

| Parpignol, a toy vendor | Tenor |

Setting: Paris, mid-19th Century

Background:

La Bohème aroused quick public response, thanks to its heart-warming melodies and absorbing drama. Many early critics, however, objected strongly to its story, its music, even its romantic freedom. Turinese writers bemoaned what they called a decline in Puccini’s powers; some dubbed the new work a mere potboiler, others dismissed it as an operina or operetta, and here in New York the Tribune critic flailed the new work as “foul in subject and fulminant and futile in its music.” In due course, however, even the critics were won over by the bubbling verve and intense fervor of the music. Today most opera-goers would rank La Bohème among their favorite operas.

Synopsis:

Act I

Scene: In the Attic.

The cold, bleak garret dwelling of the inseparable quartet, Rodolfo, poet; Marcello, painter; Colline, philosopher; Schaunard, musician, is certainly large enough to accommodate such a family. The sparse furniture makes it seem doubly spacious. For the fireplace — devoid of fire — the few chairs, the table, the small cupboard, the few books, the artist’s easel, appear like miniatures in this immense attic. Marcello, busily painting at his never-finished canvas — The Passage of the Red Sea — stops to blow on his hands to keep them from freezing. Rodolfo, the poet, gazes through the window over the snow-capped roofs of Paris. Marcello breaks the silence by remarking that he feels as though the Red Sea were flowing down his back, and Rodolfo answers the jest with another. When Marcello seizes a chair to break it up for firewood, Rodolfo halts him, offering to sacrifice the manuscript of one of his plays instead. The doomed play now goes into the flames, act by act, and as it burns, the friends feast their eyes on the blaze, but gain scant warmth from it. The acts burn quickly, and Colline, who now enters stamping with cold, declares that since brevity is the soul of wit, this drama was truly sparkling.

Accompanied by errand boys, the musician Schaunard bursts in cheerfully, bringing wood for the fire, food and wine for the table, and money — plenty of it, from the way he flashes it. To his enraptured companions he relates how a rich English amateur has been paying him liberally for music lessons. The festivities are cut short by the arrival of the landlord Benoit, who begins to demand his long overdue rent, when he is mollified by the sight of money on the table. As he joins the comrades in several rounds of drinks, he grows jovial and talkative. The young men feign shock when the tipsy landlord begins to boast of his affairs with women in disreputable resorts, protesting that they cannot tolerate such talk in their home; and he a married man, too! The gay quartet seize the landlord and push him out of the room.

Rodolfo remains behind to work as his companions go off to the Café Momus to celebrate. He promises to join them in five minutes. He now makes several fruitless attempts to continue an article, and a timid knock at the door finally interrupts his efforts. Rodolfo opens, and a young girl enters shyly. While explaining that she is a neighbor seeking a light for her candle, she is suddenly overcome by a fit of coughing. Rodolfo rushes to her side to support her as she begins to faint and drops her candle and key. He gives her some water and a sip of wine. Rodolfo recovers the candle, lights it, and, after accompanying her to the door, returns to his work. A moment later Mimi re-enters. She has suddenly remembered the key and pauses at the threshold to remind Rodolfo of its loss. Her candle blows out, and Rodolfo offers his, but that, too, soon goes out in the draft. Left in the dark, they grope together along the floor for the lost key. Rodolfo finds it and quietly pockets it. Slowly he makes his way toward his visitor, as if still searching for the key, and sees to it that their hands meet in the dark. Taken unawares, the girl gives a little outcry and rises to her feet. “Thy tiny hand is frozen” (“Che gelida manina”), says Rodolfo tenderly; “let me warm it for you.”

Rodolfo assists the girl to a chair, and as he assures her it is useless to hunt for the key in the dark, he begins to tell her about himself. “What am I?” he chants; “I am a poet!” Not exactly a man of wealth, he continues, but one rich in dreams and visions. In a wondrous sweep of romantic melody he declares she has come to replace these vanished dreams of his, and now he dwells passionately on her eyes, eyes that have robbed him of his choicest jewels. As the aria ends, Rodolfo asks his visitor to tell him about herself. “Who are you?” he asks.

Simply, modestly, the girl replies: “My name is Mimi,” and in an aria of touching romantic sentiment, she confides that she makes artificial flowers for a living. Meanwhile she yearns for the real blossoms of spring, the meadows, the sweet flowers that speak of love.

Rodolfo is entranced by the simple charm and frail beauty of his visitor and sympathizes with her longing for a richer life. The enchanted mood is broken by the voices of Marcello. Colline, and Schaunard. calling Rodolfo from the street below. As Rodolfo opens the window to answer, the moonlight pours into the room and falls on Mimi. Rodolfo, beside himself with rapture, bursts out with a warm tribute to her beauty, and soon the two of them unite their voices in impassioned song. “O soave fanciulla (“O lovely maiden” ). Mimi coquettishly asks Rodolfo to take her with him to the Café Momus, where he is to rejoin his friends. They link arms and go out and as they go down the stairs their voices are heard blending in the last fading strains of their ecstatic duet.

Act II

Scene: A Students’ Café in the Latin Quarter.

It is Christmas Eve. A busy crowd is swarming over the public square on which the Café Momus stands. Street vendors are crying their wares, and students and working girls cross the scene, calling to one another. Patrons of the café are shouting their orders to waiters, who bustle about frantically. The scene unfolds in a joyful surge of music, blending bits of choral singing, snatches of recitative. and a lively orchestral accompaniment. Rodolfo and Mimi. walking among the crowd arm in arm, stop at a milliner’s, where the poet buys her a new hat. Then the lovers go to the sidewalk table already occupied by Colline. Marcello, and Schaunard.

Parpignol, a toy vendor, bustles through the crowd with his lantern-covered pushcart, trailing a band of squealing and squabbling children, who pester their mothers for money to buy toys. As the children riot around him, Parpignol flings his arms about in despair and withdraws with his cart. Meanwhile the Bohemians have been ordering lavishly, when suddenly there is a cry from the women in the crowd: “Look, look, it’s Musetta with some stammering old dotard!” Musetta, pretty and coquettish, appears with the wealthy Alcindoro, who follows her slavishly about. Musetta and Marcello had been lovers, had quarreled and parted. Noticing Marcello with his friends, the girl occupies a near-by table and tries to draw his attention. Marcello at first feigns indifference, and when Mimi inquires about the attractive newcomer, Marcello replies bitterly: “Her first name is Musetta, her second name is Temptation!” In an access of gay daring, Musetta now sings her famous waltz, “Quando me’n vo soletta per la via” in which she tells how people eye her appreciatively as she passes along the street.

The melody floats lightly and airily along, a perfect expression of Musetta’s lighthearted nature. Presently the voices of the other characters join in — Alcindoro trying to stop her; Mimi and Rodolfo blithely exchanging avowals of love; Marcello beginning to feel a revived interest in Musetta; Colline and Schaunard commenting cynically on the girl’s behavior. Their varied feelings combine with Musetta’s lilting gaiety in an enchanting fusion of voices. Musetta now pretends her shoe hurts, that she can no longer stand, and Alcindoro hurries off to the nearest shoemaker. The moment he disappears from sight, she rushes to Marcello. The reunited lovers kiss, and Musetta takes a chair at Marcello’s table. The elaborate supper ordered by Alcindoro is served to the Bohemians along with their own. As distant sounds of music are heard, the crowd runs excitedly across the square to meet the approaching band. Amid the confusion the waiter brings in the bill, the amount of which staggers the Bohemians. Schaunard elaborately searches for his purse. Meanwhile as the band comes nearer and nearer, the people along the street grow more and more excited. Musetta rescues her friends from their plight by instructing the waiter to add the two bills together and present them to Alcindoro when he returns. A huge crowd now rushes in to watch as the patrol, headed by a drum major, marches into view. Musetta, lacking a shoe, hobbles about, till Marcello and Colline lift her to their shoulders and carry her off triumphantly to the rousing cheers of the crowd. Panting heavily, Alcindoro runs in with a new pair of shoes for Musetta, and as he slumps dejectedly into a chair he receives the collective bill.

Act III

Scene: A Gate to the City of Paris (the Barrière d’Enjer).

A bleak, wintry dawn at one of the toll gates to the city. At one side of the snow-blanketed square stands a tavern, over the entrance of which, as a signboard, hangs Marcello’s picture of the Red Sea. From within the tavern come sounds of revelry. Outside the gate a motley crowd of scavengers, dairy women, truckmen, and farmers have gathered, demanding to be let through. One of the customs officers warming themselves at a brazier saunters over to the gate and admits the crowd. From the tavern comes the sound of Musetta’s voice. Peasant women pass through the gate, declaring their dairy products to the officials. From a side street leading out of the Latin Quarter comes Mimi, shivering with cold. A violent fit of coughing seizes her as she asks one of the officers where she can find Marcello. The officer points to the tavern, and Mimi sends a woman in to call him. Marcello, rushing to her side, greets her warmly with a cry of “Mimi!” “Yes, it is I; I was hoping to find you here,” she replies weakly. Marcello tells her that he and Musetta now live at the tavern: he has found sign-painting more profitable than art, and Musetta gives music lessons. Mimi tells Marcello she needs his help desperately, for Rodolfo has grown insanely jealous and the constant bickering has made life unbearable. In a tender duet with Mimi, Marcello expresses his sympathy, and her frequent coughing only deepens his concern.

When Rodolfo comes from the tavern to call Marcello, Mimi slips behind some trees to avoid being seen. Now Mimi overhears Rodolfo complaining to Marcello about their quarreling. Just as he announces his decision to give her up, Mimi reveals her presence by another coughing fit, and Rodolfo rushes to embrace her, his love returning at the sight of her pale, fragile beauty. But she breaks away, and sings a touching little farewell song, in which she says she bears him no ill will, that she will now return to her little dwelling, that she will be grateful if he will wrap up her few things and send them to her.

Meanwhile Marcello has re-entered the tavern and caught Musetta in the act of flirting. This brings on a quarrel, which the couple continue in the street. As Mimi and Rodolfo bid each other good-by — “Addio, dolce svegliare alia matina” (“Farewell, a sweet awakening in the morning”) — their friends almost reach the point of blows in their quarrel. The music vividly mirrors the difference in temperament of the two women — Mimi, sad, gentle, ailing; Musetta, bold and belligerent — as well as the different response of the two men. “Viper!” “Toad!” Marcello and Musetta shout to each other as they part. “Ah, that our winter night might last forever,” laments Mimi. Their resolve to part weakens in the new mood of tenderness, and as they leave the scene Rodolfo sings, “Ci lascieremo alla stagion fiorita” — ‘”We’ll say good-by when the flowers are in bloom.”

Act IV

Scene: In the Attic (as in Act I).

Rodolfo and Marcello, having again broken off with their mistresses, are back in their garret, living lonely, melancholy lives. Rodolfo is at his table, pretending to write, while Marcello is at his easel, also pretending. They are obviously thinking of something else — of their happy times with Mimi and Musetta. When Rodolfo tells Marcello that he passed Musetta on the street looking happy and prosperous, the painter feigns lack of interest. In friendly revenge, he tells Rodolfo he has seen Mimi riding in a sumptuous carriage, looking like a duchess. Rodolfo

tries, unsuccessfully, to conceal his emotions, but a renewed attempt to work proves futile. While Rodolfo’s back is turned, Marcello takes a bunch of ribbons from his pocket and kisses them. There is no doubt whose ribbons they are. Rodolfo, throwing down his pen, muses on his past happiness. “Oh, Mimi, you left and never returned” (“Ah, Mimi, tu piu”), he sings; “O beautiful bygone days; O vanished youth.” Marcello joins in reminiscently, wondering why his brush, instead of obeying his will, paints the dark eyes and red lips of Musetta.

Their mood brightens momentarily as Colline and Schaunard enter with a scant supply of food. With mock solemnity the friends apply themselves to the meager repast as if it were a great feast. When a dance is proposed, Rodolfo and Marcello begin a quadrille, which is quickly cut short by Colline and Schaunard, who engage in a fierce mock duel with fire tongs and poker. The dancers encircle the, duelists, and just as the festive mood reaches its height, Musetta bursts in. She brings sad news: Mimi, who is with her, is desperately ill. The friends help Mimi into the room and place her tenderly on Rodolfo’s bed. Again Rodolfo and Mimi are in each other’s arms as past quarrels are forgotten. When Musetta asks the men to give Mimi some food, they confess gloomily there is none in the house, not even coffee. Mimi asks for a muff and Rodolfo begins rubbing her hands, which are stiff with cold. Musetta gives her earrings to Marcello, telling him to sell them to buy medicine and summon a doctor. Then, remembering Mimi’s request, she goes to get her own muff. Spurred by Musetta’s example, Colline resolves to sell his beloved overcoat to make some purchases for Mimi. In a pathetic song he bids farewell to the coat, and departs with Schaunard to find a buyer. Rodolfo and Mimi are now alone. Faintly her voice is heard: “Have they gone? I pretended to be sleeping so that I could be with you. There is so much to say.” The lovers unite their voices in a duet of poignant beauty as they recall the days spent together, of the first time they met, of how she told him her name was Mimi. Reminiscent strains of melody are spun by the orchestra as the couple dwell on their attic romance. Mimi wants to know if Rodolfo still thinks her beautiful. “Like dawn itself!” he exclaims ardently. Suddenly Mimi, coughing and choking, sinks back in a faint. Rodolfo cries out in alarm, as Schaunard enters and asks excitedly what has happened. Mimi, reviving, smiles wanly and assures them everything is all right. Musetta and Marcello enter quietly, bringing a muff and some medicine. Mimi eagerly seizes the muff, which Musetta insists Rodolfo has purchased for her. Growing weaker and weaker, Mimi at last falls asleep — or, so it seems. Marcello heats the medicine; the other men whisper together, and Musetta begins to pray. Rodolfo has fresh hope, now that Mimi is sleeping so peacefully. Schaunard tiptoes over to the bed. Mimi is not asleep — she is dead! Shaken, he whispers the news to Marcello. Rodolfo, having covered the window to keep out the light of dawn, notes the sudden change in his friends at the other end of the room. As he realizes the truth, the orchestra pounds out fortissimo chords full of tragic impact. Musetta kneels at the foot of the bed, Schaunard sinks into a chair, Colline stands rooted to one spot, dazed, while Marcello turns away to hide his grief. Rodolfo rushes across the room, flings himself on Mimi’s bed, lifts her up, and sobs brokenly, “Mimi! . . , Mimi! . . . Mimi!”

[Adapted from The Victor Book of the Opera, 1929]

Click here for the complete libretto.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Boheme.png image_description=Puccini: La Bohème audio=yes first_audio_name=Puccini: La BohèmeWindows Media Player first_audio_link=http://www.operatoday.com/Boheme.wax second_audio_name=Puccini: La Bohème

WinAMP, VLC or iTunes second_audio_link=http://www.operatoday.com/Boheme.m3u product=yes product_title=Giacomo Puccini: La Bohème product_by=Aristodemo Giorgini (Rodolfo), Rosina Torri (Mimi), Thea Vitulli (Musetta), Luigi Manfrini (Colline), Aristide Baracchi (Schaunard), Salvatore Baccaloni (Benoit/Alcindoro), Giuseppe Nessi (Parpignol), Orchestra e Coro del Teatro alla Scala di Milano, Carlo Sabajno (cond.)

Recorded 1928.

ROSSINI: Il Viaggio a Reims

This production, a combined effort of the Kirov Opera and Théâtre du Châtelet, was premiered in 2005, and has made its way to the Kennedy Center in Washington DC as a part of the Kirov’s residency here, now in its fifth year.

Minimal staging (sets by Pierre-Alain Bertola) strips the “Golden Lily Hotel” to its scaffolding, revealing the opera for what it truly is — a collection of sparkling vignettes with hardly a semblance of a plot; a glorious divertimento; a concert in costumes — but what fabulous costumes! Among costume designer Mireille Dessigy’s creations, not to be missed are the Contessa de Folleville’s outrageous hats and Corinna’s ancient regime version of fuzzy slippers. The Russian general’s garb complete with a sailor’s tunic and a white horse (yes, an actual — and impressively well-behaved — animal) is hilarious. As for Corinna’s entrance costume, capped with a fantastic feather turban and illuminated from within by flashing electric lights, it is beyond description, and would surely land some Hollywood star enterprising enough to steal it a place on the “worst dressed, yet most memorable” red carpet list. The “English golf dandy” outfit of Chevalier Belfiore, on the other hand, was funny but not particularly convincing.

The Kirov’s performance started well before the opera began, with the orchestra players (with their instruments) and singers (with their luggage) making their way to the “hotel” from the auditorium, greeting the audience in two languages (none of them Italian), and then negotiating stage space with the “cleaning crew,” mops and vacuums in hand. The conductor — maestro Gergiev himself — did not carry a suitcase, was relieved of his coat by one of the choristers, but would keep his hat on throughout the evening. Both the conductor and the orchestra (dressed in white and reduced almost to a chamber group for the occasion) were positioned on stage, with a harpsichordist placed on the proscenium and dressed up in full ancient regime regalia, complete with high heels and a powdered wig. Similarly dressed was a harpist wheeled onto the stage on a special platform whenever her services were required to accompany Corinna the poetess (the lovely Irma Gigolashvili); and a fabulous flutist (unfortunately not identified in the program) who performed her second act solo flawlessly, all the while engaged in a clever pantomimed “duet” with Lord Sydney (Eduard Tsanga).

Throughout, the production (directed by Alain Maratrat) was filled with stage business — always energetic, often clever, and occasionally detrimental to sound production: for instance, practically nothing performed on the back section of the scaffolding (behind the orchestra) made it into the hall. On the other hand, plenty of singing (and some very funny acting) occurred in the orchestra — among the orchestra seats, that is. This clearly delighted the audience but presented a significant challenge to ensemble performance — a challenge that the young troupe, to their credit, met and triumphed over, even in the lightning-fast stretti. Overall, the vocal performance of the young cast, including some tremendously difficult passagework, was almost uniformly superior: Anastasia Kalagina as Madame Cortese impressed with the precision of her coloratura; Larisa Yudina as the Contessa proved herself a comic talent, yet was ever ready with those breathtaking E-flats. Dmitry Voropaev as Belfiore, Daniil Shtoda as Count di Libenskoff, Vladislav Uspensky as Baron di Trombonoc, and particularly Nikolay Kamensky as basso buffo Don Profondo were all excellent. Anna Kiknadze as Melibea was less impressive, but she did occasionally enjoy her moments of glory (unfortunately, the final polonaise was not one of those moments). Only Alexey Safiulin as Don Alvaro was truly disappointing: he did well in the ensembles, but the solos — including the gorgeous “fake flamenco” song Rossini had smuggled into the grand finale — were almost entirely lost. The chorus — members of the Mariinsky Academy of Young Singers — acted lustily and sang well; the orchestra sound was clean, crisp, and tastefully “classic” — in fact, barely recognizable as coming from an orchestra better known for the sweeping romantic sound of its Tchaikovsky and Wagner productions.

Grand drama devotees might find Il Viaggio a Reims annoyingly fluffy. Opera purists could object to the coloratura occasionally getting lost in the stage business or covered with the audience’s laughter. Yet, to those who think of opera as primarily a theatrical spectacle, the Kirov production proves deliciously watchable. It is just what King Charles X of France had ordered from his favorite composer — a splendid and frivolous piece of entertainment for a very special occasion.

Olga Haldey

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Il_Viaggio_Kirov.png image_description=Gioachino Rossini, Il Viaggio a Reims (Kirov Opera) product=yes product_title=Gioachino Rossini: Il Viaggio a Reims product_by=Kirov Opera and Orchestra, Valery Gergiev (cond.)Kennedy Center, Washington, D.C., 27 January 2007

EDER: Musik für die Felsenreitschule

Such is the case with two pieces by the Austrian composer Helmut Eder (1916-2005), whose Divertimento, op. 64, “…Missa est”, op. 86, are designated as Musik für die Felsenreitschule, that is, the outdoor riding school that is used for performances at the Festival. These two recordings date from two distinct performances, the Divertimento from 1976 and “…Missa est” from 1986, and from all indications, they are the premiers of the respective works.

In his fine notes that accompany the recording, Gottfried Kraus profiles Eder’s style, but aside from various influences that he discusses, it is possible to characterize the music as approachably modern. Eder relies on tonal structures, but his music uses modern techniques to arrive at them. Thus, dissonant counterpoint, ostinato patterns, pitch sets, and antiphonal textures are elements that shape such a work as the Divertimento. Not ends in themselves, the techniques are fully developed within the context of each piece. In fact, the textless soprano part in the Divertimento offers a fresh sound in the simple and poignant contrast it offers in the context of the prominent brass and percussion. This is particularly effective in the last movement, the section labeled “Canto II,” with which the work ends. The coloratura soloist, May Sandoz, offers a pliable sound in the extended melismas that Eder gave the voice. Various modal patterns are part of the vocal writing, which relies characteristically on longer lines, in contrast to the more motivic ideas that are accorded the instruments. A four-movement work, the piece itself is engaging for the timbres it brings, and the musical space it defines broadens the idea of the conventional Divertimento with its use of orchestral groups and solo voice.

In his Mass “…Missa est,” Eder offers a brash perspective on the traditional form. In theits instrumental opening of the Kyrie, the sound world is outlined in detail, with dissonant sonorities, stark sonorities, and extroverted percussion, which retreat to the background when the chorus enters. Even there, the chordal textures allotted the male voices are a springboard for the improvisatory-like lines of the women. When Eder brings choral forces together, the resulting unity serves the text well, as the traditional words find new declamation in this work from 1986. While the Kyrie can be perfunctory in the Mass settings of some composers, Eder’s is impressive for the weight he gave it, which balances the scope of the Agnus Dei with which the piece concludes.

Likewise, the Gloria is equally noteworthy for the festive mood created by giving the voices fanfare-like motives that complement the music accorded the instruments. Just as he achieves a full sound, Eder brings in the solo voices, a gesture that draws the listener closer to the text, which finds a thoughtful setting in this movement. A movement that lasts more than twenty minutes, the Gloria stands out with its length and the prominence that comes with such emphasis. Where conventional settings might have the Gloria and Credo roughly proportionate in length, the latter text is presented with less pomp. In fact, the chant-like treatment allows the text of the Credo to be understood clearly, but it is clearly less prominent. In arriving at this structure, Eder suggests, perhaps, the way in which simple faith may have retreated into the background in contemporary culture.

Yet after the almost hypnotic Credo, the bombastic sounds of the Sanctus return to the celebratory tone that the composer established in the Gloria. Here the chordal sonorities in the voices play off various sound masses in the instruments. In the freely dissonant accompaniment that underscores the bass solo, Eder has created some shimmering sounds that eventually give way to an austere conclusion, before the discrete Benedictus, which makes wonderful use of solo voices.

With the Agnus Dei, Eder returns sounds reminiscent of some sections of the Kyrie, with the voices intoning the well-known text in the chant-style found in the Credo. As he allows the movement to develop, Eder uses the kinds of sinuous lines found in the Kyrie, and eventually brings in solo voices to carry the text. In the final iteration of the tripartite text, “Agnus Dei qui tollis peccata mundi”(“Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world”), the concluding invocation of “dona nobis pacem” (“grant us peace”) receives a subtle and quiet treatment. The more extroverted sounds associated with the jubilation of the Gloria and the celebration of the Sanctus give way to music that is more intimate, as the peace ends quietly. It is not the more aggressive “Dona nobis pacem” found in Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis, a peace that is challenged by martial sounds. Rather, Eder resolves the movement and with it the entire Mass by shifting to chamber-like sonorities that evidently resonated with the audience, whose applause is preserved in this recording.

Conducted by Leopold Hager and performed by the ORF-Chor, Vienna, the Arnold Schoenberg Chor, and the Radio Symphony Orchestra, Vienna, this is a convincing recording of a work that is probably known best from its premiere at the Salzburg Festival. The soloists are certainly noteworthy, with such accomplished singers as Eva Lind, Marjana Lipovsek, and Robert Hall, adding to the attraction of the piece. More, this recent setting of the traditional Catholic liturgy demonstrates a further artistic direction for this venerable form. A different side of the famed Salzburg Festival, this recording includes new works certainly contribute to the rubric “Festspiel Dokumente” to deepen the understanding of the kinds of music celebrated at this truly world-class event.

James Zychowicz

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Eder.png image_description=Helmut Eder: Musik für die Felsenreitschule product=yes product_title=Helmut Eder: Musik für die Felsenreitschule product_by=Mozarteum Orchester Salzburg, Theodor Guschlbauer (cond.)Salzburger Festspieldokumente product_id=Oehms Classics OC539 [CD] price= product_url=

ROSSINI: Semiramide

We are told this was a live recording for Austrian radio made in 1998. At that time the lady was 52-years of age and had already a career of thirty years behind her. Amazing, of course when one thinks of many singers who have spoiled their voices after half the amount of years. The result is still very fine: an object lesson as to what belcanto technically means; how to sing coloratura, how to embellish, how to trill. To be honest, one can regret the fact she didn’t record the role earlier. “Bel raggio” is fine but not quite sung with the same freedom as she did on her French/Italian aria record on EMI from 1982. I’m surprised, too, that the recording team didn’t ask her to re-record the top note at the end of the cabaletta (or didn’t use electronic wizardry) as it falls painfully flat and it is not a note one wants to hear everytime one plays this set; but honest it surely is.

Nevertheless not everything is a liability. The voice is somewhat more broad, more dramatic than in 1982 and this corresponds far better with the character of the role. Bernadette Manca di Nissa displays a fine, rounded mezzo though there is not much in her characterization that remind us of a young exuberant warrior which we remember well Marilyn Horne in the famous 1966 Decca recording. This is already more Azucena than Arsace and time. Ildebrando D’Arcangelo cannot quite compete with Sam Ramey at the height of his powers but the voice of the Italian bass is fuller, more beautiful and less dry than Rouleau’s in the Decca. The one singer in the recording under review fully on Gruberova’s level is Juan Diego Florez at the outset of his big career. He has the style and already knows all the ins-and-outs of Rossini. Moreover, he brings with him the sunny colours of a Mediterranean ancestry, which at the time immediately eclipsed fine Rossini singers like Blake and Ford — formidable technicians but without the Peruvian’s natural talent.

Marcello Panni’s conducting is not very inspiring, though one can never be sure on a prima donna’s label that the conductor has the last word on tempi. Even Richard Bonynge, always accused of indulging his wife, brings out the more tragic elements of this opera seria. With Panni one too often has the feeling he is conducting one of Rossini’s comic operas. In the end this rather well-sung and sometimes more homogenous sounding version cannot quite compete with the Sutherland-Horne-Bonynge version where each of the principals is superior to the singers in this recording.

Jan Neckers

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Semiramide.png image_description=Gioacchino Rossini: Semiramide product=yes product_title=Gioacchino Rossini: Semiramide product_by=Edita Gruberova (Semiramide), Bernadette Manca di Nissa (Arsace), Hélène Le Corre (Azema), Ildebrando D'Arcangelo (Assur), Juan Diego Flórez (Idreno), Julian Konstantinov (Oroe), José Guadalupe Reyes (Mitrane), Andreas Jankowitsch (Nino's ghost), Wiener Konzertchor, Radio Symphonieorchester Wien, Marcello Panni (cond.) product_id=Nightingale NC207013-2 [3CDs] price=$55.08 product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/Drilldown?name_id1=10388&name_role1=1&comp_id=32759&genre=33&bcorder=195&label_id=1299VERDI: Aida

Perhaps avid fans of the actress will want this, as she is in her youthful prime here and, despite some rather heavy "darkening" make-up, a gorgeous spectacle in herself. Certain devotees of dated, even corny cinema may find some pleasure as well.

But for those who love the opera, this DVD should be avoided. Cut down to about 90 minutes, the film employs a dull narrator linking the scenes with rudimentary plot points, spoken in English over music. The first words? "As the opera begins...." That is damage enough. However, if the film were otherwise in good condition, some enjoyment might still be found. The film is not, however, in good condition. There are many slight skips and jumps in the editing. The overture is butchered, starting with the "triumphal march" before cutting back to what Verdi actually composed. The director even interposes a flashback at one point, showing the havoc the Ethiopians (looking like extras from a bad Tarzan movie) had wreaked on the Egyptians. The climax is butchered by both poor film quality and bad direction, and as a capper, recorded applause ends the show. Incomprehensible. The sets and costumes do have an old-time appeal, but the cinematography has lost its luster, with the colors often washed-out.

Besides Loren, the other actors try their best, although the lip-syncing is often inadequate. Only the Radames (sung by Giuseppe Campora) is weak, a skinny pretty boy named Luciano Della Marra.

The DVD offers no booklet (at least the review copy didn't). Neither are subtitles provided, and there are only a few chapter selections. But never mind. Even with those features, this DVD would not be a satisfactory Aida for any but those understandably besotted with the beauty of the young Loren.

Chris Mullins

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Aida_DVD.png image_description=Giuseppe Verdi: Aida product=yes product_title=Giuseppe Verdi: Aida product_by=Sophia Loren - Aida; Renata Tebaldi - Aida (singing voice); Lois Maxwell - Amneris; Ebe Stignani - Amneris (singing voice); Luciano Della Marra - Radamès; Giuseppe Campora - Radamès (singing voice); Afro Poli - Amonasro; Gino Bech - Amonasro (singing voice); Antonio Cassinelli - Ramfis; Giulio Neri - Ramfis (singing voice). Directed by Clemente Fracassi. Screenplay by Clemente Fracassi. Rome Opera Ballet Corps. Italian State Radio Orchestra, Giuseppe Morelli (cond.). product_id=Qualiton 616 [DVD] price=$18.99 product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/Label?&label_id=3023Qualiton 616

Nuovi documenti pucciniani

La Biblioteca Statale di Lucca ha recentemente acquisito una delle raccolte più cospicue di materiale pucciniano: si tratta della collezione Bonturi-Bovenzi costituita da oltre cinquecento pezzi che provengono dall'ambito familiare di Puccini (Ida Bonturi, sorella di Elvira, e suo marito Giuseppe Razzi).

La Biblioteca Statale di Lucca ha recentemente acquisito una delle raccolte più cospicue di materiale pucciniano: si tratta della collezione Bonturi-Bovenzi costituita da oltre cinquecento pezzi che provengono dall'ambito familiare di Puccini (Ida Bonturi, sorella di Elvira, e suo marito Giuseppe Razzi).

January 26, 2007

Life in tune

Jerry Fodor [Times Literary Supplement, 17 January 2007]

Jerry Fodor [Times Literary Supplement, 17 January 2007]

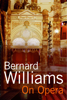

Bernard Williams

ON OPERA

224pp. Yale. £19.99.

0 300 08976 7

There are, in principle, two quite different kinds of opera books: the ones that are about opera and the ones that are about operas. There aren’t (to my knowledge) many of the second kind that are very good; and there are practically none of the first kind. It would be lovely if someone were to write a good book about opera, since the medium is a conundrum both for its devotees and for aestheticians. The litany of complaints is familiar: most libretti cannot be taken seriously; but for the music, they couldn’t hope to hold the stage.

Polish & Pastoral Charm

By George Loomis [NY Sun, 26 January 2007]

By George Loomis [NY Sun, 26 January 2007]

Handel's "Acis and Galatea," like his later "Semele," is rightly considered an opera, even if it went by other labels during the birth of English opera. Both works have rightly been accorded recent productions at the New York City Opera, "Semele" just last fall. But "Acis and Galatea," it seems, was originally given by quite modest forces, in a performance with soloists doubling as choristers and perhaps as few as seven or eight instrumentalists.

January 24, 2007

RAMEAU: In Convertendo Dominus

The prominent title is In Convertendo, a grand motet from Rameau's early years as a church organist; and the box is labeled Concert/Documentary. Things should be the other way around: this is in fact a DVD presenting an excellent documentary, The Real Rameau, with In Convertendo and three movements from the Pièces de Clavecin en Concerts as lagniappe (Lousiana French for "a small gift thrown in free along with a purchase").

Even such figures as Handel, Bach, Vivaldi, and Telemann are not well-supplied with documentaries on their lives and works, so a presentation of Rameau, certainly the least well-known of the great composers of the Baroque, is especially welcome. Rameau, who I like to think of as Puccini to Lully's Verdi, had the greatest second act in the history of music, making his debut as opera composer in Paris at the age of 50 after decades in the provinces as an organist (imagine J.S. Bach moving to Italy in 1735 to write operas!). The documentary begins with a dramatized discussion of the great composer lifted from Denis Diderot's Rameau's Nephew (you can read the complete text here), and moves through the course of Rameau's career with the engaging William Christie as our guide, along with musicologist Sylvie Boissou of the Institut de recherché sur le patrimoine musical en France, illustrated by clips from In Convertendo, the Pièces de Clavecin, and the operas (there are now four available complete on DVD – Les Indes Galantes, Platée, Les Paladin, and Les Boreades). Christie and Boissou do a fine job of explaining, within the context of a one-hour film, what is exceptional, striking, immortal about the work of this composer. Given more time, I would have loved to see more detail on the theatrical dance of the time (we are told that Rameau was the greatest composer for the dance before Stravinsky, but we are not shown why this is so), and perhaps some discussion of how French operatic singing differed from the Italian vocalism of the period (that it differed greatly is evident from the writings of such Italophiles as Charles Burney, who execrated French singers).

After the operatic stimulation of the documentary (who can see the singing frog-princess, Platée, without wanting to see the whole of the opera?), the more restrained idiom of the motet, as fine as it is, and as fine as its performance is, is a bit of a let-down. Had Rameau never composed for the stage, this work would have suffered the fate of all its fellows produced for the church – to remain unsung in a library archive – and we should never have had this documentary, a documentary which is a fine introduction to one of the greatest of composers and his works.

Tom Moore

image=http://www.operatoday.com/OA0956D.png image_description=Jean-Philippe Rameau: In Convertendo Dominus product=yes product_title=Jean-Philippe Rameau: In Convertendo Dominus product_by=Nicolas Rivenq, Sophie Daneman, Jeffrey Thompson, Olga Pitarch Orchestra and Chorus of Les Arts Florissants, William Christie (cond.) product_id=Opus Arte OA 0956 D [DVD] price=$20.99 product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/album.jsp?album_id=140005RAMEAU In Convertendo, plus The Real Rameau (by Reiner E. Moritz). Nicolas Rivenq; Sophie Daneman; Jeffrey Thompson; Olga Pitarch; Les Arts Florissants; William Christie. Béatrice Martin, Patrick Cohen-Akenine, Nima Ben David; Serge Saitta. OPUS ARTE OA 0956 D (All regions).

MAHLER: Songs of a Wayfarer; Symphony no. 1 in D

Presented in two discrete concerts, Mahler’s Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen was recorded on 26 September 1991, and the First Symphony from 12 February 1985, with both given at the Royal Festival Hall, London.

A fine interpreter of Mahler’s music, Thomas Hampson was in fine voice for the 1991 performance, and the recording captures his sound quite well. If anything, his voice sounds more forward than the ensemble accompanying him, with the orchestral timbres blended appropriately. Tennstedt’s tempos support the vocal line well, with the interludes sometimes shaped to enhance the texts. With “Ging heut’ morgen übers Feld,” for example, the orchestral slowing before the final strophe is essential to the emphasis that Hampson gives to the final two lines that convey the reversal of tone at the end of the song: “Nun fängt auch mein Glück wohl an? / Nein, nein, das ich mein’, / Mir nimmer blühen kann!” Here the vocalist and conductor must work hand-in-glove, and the performance is exemplary in conveying the shift in mood that is crucial to understanding the song and the rest of the cycle.

As to Hampson’s vocalism, the upper range is quite effective, and demonstrates the kind of lyricism that endeared him to audiences around the world. He shows his capacity to use register as an expressive device, and thus enhances Lieder like these without forcing onto the music affectations that compete with the musical text. A full voice, Hampson is by no means reluctant to start the third song aggressively, and thus suggest the almost hallucinatory state of mind that is crucial for “Ich hab’ ein glühen Messer.” Yet when the music calls for subtlety, he has the capacity to do so with full support, as in the subdued, but never vapid, approach he has given to “Die zwei blauen Augen.” Likewise, Tennstedt’s control of the orchestral never ventures into the singer’s realm, and always serves to support the characteristically Lieder-like style of this orchestral song cycle.

With the recording of Mahler’s First Symphony, a work for which Tennstedt was well known, and this performance predates the esteemed recording of the piece that he made with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in 1991. As difficult as it can be to describe conductors’ approaches, it is otherwise with Tennstedt. In this work he offers a spaciousness that allows the ensemble to render this demanding score effectively. The relatively slow opening movement allows the various motives to emerge clearly, without forcing the passage that translate the vocal line from “Ging heut’ morgen übers Feld.” At the same time, the pacing gives the brass – especially the trumpet – the opportunity to use a sweet, ringing sound that comes across clearly as an individual color. Likewise, it is a fine tempo for demonstrating the cohesiveness of the strings that Mahler relied on to for the timbral core of much of the first movement.

The second movement, the Scherzo, conveys the sense of a Landler in its easy, almost rocking tempo. This movement has its challenges in the lengthy stretches that have no tempo markings to guide the conductor and, at the same time, shorter passages that are in contrast overly marked by Mahler. The conductor must resolve the issues himself, and Tennstedt has done so well, with nuances of accelerandos and ritardandos that underscore the music without become mannered or unnatural. Ultimately the Scherzo must accelerate the weight of its own texture to the climax that precedes the central, lyrical section, and Tennstedt did so well in this performance, with the center of the movement convincingly delicate.

For some Mahler’s innovation is the ironic funeral march of the third movement, and the recording captures that tone. The slow tempo that Tennstedt took in the opening section forced the unusual solo instruments to become prominent. There is a hint of a reaching in the tuba that does not sometimes occur, and that is entirely appropriate to the style of the piece. Likewise, the Bohemian wind band sounds – sometimes suggested to be influenced by Klezmer ensembles – is sufficiently colorful without becoming a caricature. The details, which are always essential in successful performances of Mahler’s music, are evident here, with trills that are long enough to be heard clearly, but never out of character. Yet the middle section, the passage that Mahler derived from “Die zwei blauen Augen” has a cantabile quality that sets it apart from the wry humor with which the movement opened. Here, the quotation of the song is as crucial to the direction found in the rest of the Symphony as the ritardando – almost a piacere style – that must occur before the final few lines of “Ging heut’ morgen übers Feld.” It is as this point that Tennstedt sets the tone that is resolved and developed in the Finale. Thus, the attacca connection between the third and fourth movements is a critical element that must occur, and it is handled well in this concert performance, where no audience noise is evident.

Again, the aspect of spaciousness that Tennstedt brought to the opening movement is essential to his interpretation of the Finale. Never do the brass sound rushed or pushed prematurely to the brink of their abilities. At the same time, they never overbalance the string textures that Mahler used the movement, but rather color it. Here and there it is possible to hear some entrances that betray the recording as a live performance, but overall it holds together in ways that have sometimes escaped conductors in studio recordings. The anthem-like tone of the final section of the movement takes the listeners to the musical climax without allowing the coda to seem an afterthought. It is an effective performance that deserves to be heard in order to appreciate both Tennstedt’s legacy and the capacity of the London Philharmonic for performing this repertoire.

James L. Zychowicz

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Mahler_Tennstedt.png image_description=Gustav Mahler: Songs of a Wayfarer; Symphony no. 1 in D product=yes product_title=Gustav Mahler: Songs of a Wayfarer; Symphony no. 1 in D product_by=Thomas Hampson, baritone; Klaus Tennstedt, conductor; London Philharmonic Orchestra. product_id=LPO-0012 [CD] price=$16.99 product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/album.jsp?album_id=138026Carmen, Royal Opera House, London

By Richard Fairman [Financial Times, 24 January 2007]

By Richard Fairman [Financial Times, 24 January 2007]

You could have read it in the cards: a new production that was dubbed ineffectual in December, cancellation of the singer of the title role, a second cast sharing little in style or background. Fate had not dealt this revival a strong hand.

JANACEK: Káťa Kabanová

Since then, it is gradually on its way to becoming a repertory piece mainly due to directors vying with each other for trying their hands and ideas on a piece which lends itself to many an interpretation. My last Káťa was at the Brussels Munt and was played without a pause as if the lady falls in love, deceives her husband and commits suicide in the blink of an eye. Janacek wouldn’t have loved it as the last act takes place two weeks after the second one. The director had the brilliant idea of placing the piece in one of these dreary Russian “kommunalka’s” (common apartments) in the early 1960s. These were, and probably still are, places where gossip is rife and can be deadly indeed. Still, there is the small problem of the horse sleighs arriving and leaving, so magically invoked by Janacek’s orchestra and they were passed over as being contrary to the director’s concept. And in the midst of Chroestjov’s anti-religion campaign, I severely doubt the whole Kommunalka would enthusiastically have sung the praise of Easter and Orthodoxy.

Those ‘small’ problems don’t exist on record and therefore the listener can use his or her own fantasy if need be as everything is in the nervous short melodies so typical for the composer. This recording was issued in the Decca “Classic series” and rarely this definition will have been so right on the mark. Thirty years after its appearance on the market it is still unsurpassed though honesty obliges me to say that competition is small, which proves that the record buying public is not too fond of the score shorn from its strong theatrical impact. Only five complete performances exist; probably because the opera on record indeed has less striking musical themes than present in Jenufa. The first 1959 Czech version is a poor affair as to sound and singers, notwithstanding the fact that it was an all-Czech cast. In 1977 came the issue under review. Twenty years after this classic recording the same conductor once more led a new version but for Benackova the title role came rather late in her career. The latest version in the vernacular, conducted by Cambreling, has Denoke and Kuebler in the title roles at the Salzburg Festival in 2001. I never heard the set because reviews were not very enthusiastic, deploring Denoke’s harsh sound as Káťa and Kuebler’s dry tone as Boris. Those two singers were the principals in my Brussels performance as well and I indeed got away with the impression they were good actors and very mediocre singers.

Several DVD’s prove that Elisabeth Söderström who sings the title role in this issue knew how to act convincingly but with her there is the voice as well and what a beautiful voice it is on these CD’s: very feminine, rich, sensual and ringing during emotional climaxes. The silvery sound of her early years is still there but the strength is there too and as this was the first recording in her Janacek-cycle the voice is still fresh at 49-years of age. Striking is her enunciation. Even when one doesn’t speak or understand Czech like myself, one can still compare her interpretation with her Czech colleagues and I for one don’t hear a difference in pronunciation or emphasis on syllables. In those years rumors started to go around that there was a new good lyric tenor behind the iron curtain. Dvorsky made his West-European début as the Italian tenor at the Vienna opera in the same year he recorded this set and imaginative casting this is; going for a young promising unknown. I’ve never known him singing better with that unforced beauty that some of the old hands at the Met maybe remember from his two Traviata performances in 1977. Too soon his voice would thicken so that by the time he became a regular there was not much to enjoy anymore.

Kniplova was a very successful Kabanicha at the Prague opera but as this is a recording and not a DVD the aural impression is important. Some fans will probably argue that the sour sound corresponds with the mentality of Kata’s mother-in-law but I have doubts. The many Aidas, Brünnhildes and Leonores had taken their toll. As the husband Vladimir Krejcik is very convincing. But so are all small-bit players with a special mention for Zdenek Svhela in the important role of chemistry professor. I have rarely heard a more impressive performance by an almost voiceless comprimario tenor. Nevertheless the voice fits the role to a T.

Charles Mackerras immediately jumped to the forefront of Janacek conductors with this subtle and inspired reading, slowly building the tension so that one already feels the inevitable end during the intermezzi. Of course he has at his disposal the Vienna Philharmonic and he profits from their honeyed sound while at the same time always and scrupulously supporting his singers; never using this magnificent orchestra to overwhelm them. And he has a producer and recording engineer who cooperate and don’t bury the singers in orchestral sound as happens in the second Mackerras-Benackova recording of 1997.

I don’t know the 1989 re-issue of this classic set but I’m often cross at the ways labels just throw their older recordings on the market, more often than not skipping the original interesting essays that accompanied the LP versions. I’m glad that for once the very readable article by John Tyrell plus Mackerras’ personal views are printed and they should surely be read before playing the CD’s. If I remember well the set got the Gramophone’s Record of the Year award at its first appearance. It remains the set by which all new efforts will be measured.

Jan Neckers

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Kata.png image_description=Leoš Janáček: Káťa Kabanová product=yes product_title=Leoš Janáček: Káťa Kabanová product_by=Elisabeth Söderström (Káťa), Petr Dvorsky (Boris), Nedezda Kniplova (Kabanischa), Vladimir Krejcik (Tichon), Libuse Marova (Varvara), Dalibor Jedlicka ((Dikoj), Wiener Staatsopernchor and Wiener Philharmoniker conducted by Charles Mackerras. product_id=Decca 475 7518 [2CDs] price=$22.98 product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/album.jsp?album_id=135840Plain Speaking and Singing on Copland’s Family Farm

By VIVIEN SCHWEITZER [NY Times, 23 January 2007]

By VIVIEN SCHWEITZER [NY Times, 23 January 2007]

Aaron Copland worried about the durability of “The Tender Land,” his opera about a traditional, humble, rural 1930s family suspicious of outsiders and their morals. But it seems uncannily relevant: contemporary America is still often touted as a place whose small-town heartland, inhabited by plain-spoken, wary and conservative folk, is framed by cities teeming with deviants and elitists.

January 23, 2007

BROSSARD: Grands Motets

Over the last decade the works, chiefly vocal, of this seemingly peripheral figure, who spent his career in Strasbourg and Meaux, have been published in modern editions.

This superb disc by Coin and company, reissued here after its initial release on Astrée in 1997, presents the three grand motets by the composer. In Convertendo, on a text also used by Rameau, is an almost twenty-minute long piece full of joyful, dancing music to reflect the end of Israel's captivity (“then was our mouth filled with laughter, and our tongue with joy”). The style is reminiscent of Charpentier, with obligato flutes and oboes added to the strings of the orchestra, or indeed of Purcell’s choral works from the same decade. The Miserere is a text for Holy Week, altogether darker in character. The largest piece here is the Canticum Eucharisticum Pro Pace (Eucharistic Song for Peace) written to celebrate the treaty making Strasbourgh officially a part of France in 1698, a work of more than forty minutes, built on a text selecting verses from various parts of the bible. The compositional challenge here is to create a work with a structure to support such length, setting a lengthy text with no narrative, and no inherent structure, and within an idiom which is closer to the style of the verse anthem than to the cantata or oratorio with discrete numbers varying in character, orchestration, number of performers etc. In spite of the problematic character of the text, Philidor creates much memorable music, especially the spirited Amen which closes the work.

Not every listener will be attracted to these motets, which demand close attention to the interaction of musical setting and text to be appreciated (you can’t simply close your eyes and let the music wash over you), but Coin’s interpretations, and the excellent singing and playing by his forces, show an original and interesting composer, capable, fresh, tuneful, worth getting to know. (A tiny quibble: setting the text of the booklet in small blue type on a black background was not calculated to make it readable – rather the reverse).

Tom Moore

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Brossard.png image_description=Sébastien de Brossard: Grands Motets. product=yes product_title=Sébastien de Brossard: Grands Motets. product_by=Ensemble Baroque de Limoges;Accentus Chamber Choir; Christophe Coin, conductor. product_id=LABORIE LC02 price=$16.99 product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/album.jsp?album_id=142761Saving the Song

George Loomis [NY Sun, 23 January 2007]

George Loomis [NY Sun, 23 January 2007]

In January 1994, an array of singers assembled in Carnegie Hall to celebrate Marilyn Horne's 60th birthday. Though any opera house would have envied the talent on hand, these musicians didn't sing opera — they sang songs. Ms. Horne's brilliant career as a mezzo-soprano was far from over, but she had embarked on a new crusade: the song recital. Ms. Horne had recognized a decline in its popularity, and she resolved to do something about it.

OONY Gives Rare Performance of Rossini's Otello

Though these arguments hold much weight, they also have little to do with Rossini’s expressive and thoroughly enjoyable score, as was evident in the Opera Orchestra of New York’s concert performance of the work on Wednesday night at Carnegie Hall.

Shakespeare’s work was not as well-known in northern Italy at the time of the opera’s composition, perhaps accounting for the free treatment that the story received. Berio’s retelling of the classic tale makes such a mess of things that there is little left of the original drama but the names of the characters. Lord Byron wrote of the opera in 1818: “They have been crucifying Othello into an opera,” and in my mind he spoke the truth. Indeed, the story never leaves the shores of Venice, the signal handkerchief becomes a furtive love letter, Desdemona is stabbed rather than strangled, and Jago’s role in the drama is lessened while the peripheral Rodrigo becomes integral.

Regardless, the work was hugely successful in the nineteenth century, its popularity lasting until Verdi’s Otello overtook it in the operatic canon. I would posit that the inevitable association of the two works is the principal reason that Rossini’s now lesser-known interpretation has fallen into obscurity as much as it has. Comparisons inevitably paint the earlier in a bad light by virtue of its much-maligned libretto.

Seen as the product of Rossini, the work is well worth its weight in gold. There are some truly beautiful moments, though it admittedly lags a bit in the middle. The opening, for instance, features not one, not two, not even three. . . but FOUR solo tenors singing their hearts out in one of the most exciting moments of tenor multiplicity in the repertoire. The Act Two confrontation between Otello and Rodrigo is also a moment of high drama, and Desdemona’s Willow Song is as hauntingly beautiful as is the more widely-known Verdi version.

The night also belonged to the performers that realized the impossible and sublimely beautiful bel canto score, for the work cannot stand on its own without talented virtuosos. In fact, this opera has always been at the mercy of willing and able singers; an abundance of virtuosic tenors in Naples precipitated the composition of myriad vocal fireworks for the tenor voice. The cast was led by veteran Rossini interpreter Bruce Ford, a last-minute stand-in for Ramon Vargas. Ford sang a lot of notes on Wednesday night, all with confidence and ease. Equally impressive was Kenneth Tarver as Roderigo, whose lyricism and light touch complemented the role. His high-lying aria, Ah, come mai non senti, was one of the best moments of the night. Solid too was Robert McPherson as the villainous Jago. His voice was that much louder, harsher than his colleagues’— well-suited for the antagonist. In the men’s camp it would be remiss not also to mention Gaston Rivero as the Doge (and later as the Gondolier), the fourth component in the opening.

The preponderance of tenors on the stage precludes any solo female voices for the first half hour of the work. Furthermore, in a seemingly concerted effort to keep the tessitura of the ensemble in the human voice’s middle range, the role of Desdemona is written for a mezzo. When we finally meet Desdemona, she remains a peripheral character — there is no entrance aria for her, nor is there ever a love duet. Ruxandra Donose nevertheless sang the role beautifully, and the impassioned Willow Song was the crown jewel of the concert.

If there was a drawback to the performance, it would be that the orchestra was not prepared, and perhaps more to the point, unenthused about the performance. It is eternally difficult to create cohesiveness in an opera orchestra, especially one that performs together only a few times per year. Still, the group was sloppier than most: brass instruments fracked, there was at least one blatant wrong note, and entrances were not together. On the other hand, the members of the orchestra performed solos beautifully. The virtuosic instrumental passages typical of Rossini were right on, and harpist Grance Paradise, Desdemona’s partner in the Willow Song, was as stunning in the aria as the mezzo.

So hats off to Eve Queler and the Opera Orchestra of New York, for performing such an undervalued work. Queler has long been a champion of lesser-known opera, and her choice of programming here was excellent. Carry on Ms. Queler!

Sarah Gerk

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Bruce_Ford_Otello.png image_description=Bruce Ford as OtelloGustav Mahler. Letters to His Wife

Whether additional correspondence will in the future surface, the model presented here by the editors, and in the present revised translation, should prove to be a critical yardstick which would surely accommodate subsequent additions.

Although previous collections of the Mahlers’ letters have been issued in numerous preliminary and corrected editions, Beaumont lays forth convincing evidence for his translation as well as emendations to the 1995 German edition. For his revised English version of the German original, both accessibility and accuracy have been guiding principles. In the Foreword and — just as pointedly — the “Preface to the English Edition” Beaumont makes clear from comparative charts and commentary that a significant amount of correspondence appears here in English for the first time. Further, since the appearance in 1995 of the German edition of the letters, both the release of material from the Moldenhauer archives and the publication of Alma Mahler’s early diaries (Tagebuch-Suiten) have yielded a more complete picture of the decade or so of nearly regular correspondence.

The organization of the present edition and translation differs from previous attempts to catalogue and make accessible the letters and related material. As an example, in the edition of Alma Mahler, Gustav Mahler: Memories and Letters (3rd revised ed. and trans., D. Mitchell, B. Creighton, K. Martner) the diary-entries and letters were presented in two separate parts of the volume. Beaumont’s edition, by contrast, attempts to integrate both aspects by interspersing the letters with excerpts from the diaries or recollections, and by inserting regular editorial commentary or elaboration as an aid to the reader. At the same time, surviving entries on postcards and telegrams directed by Gustav to Alma Mahler are included chronologically as equivalent testimony with the letters. Finally, because of the transfer of significant material from the Moldenhauer archives to the Bavarian State Library, individual dates for letters have been verified or corrected on the basis of new, available evidence.

Since the translation of letters which appeared in both the new and previous editions differs — for the most part — in style, we may concentrate on that which the present edition offers as supplementary data. Beaumont has devised a key to indicate, among other matters, 1) letters or communications that have not previously been published, and 2) portions of letters with passages marked that had formerly been “suppressed.” These passages are identified with parenthetical marking (<…>) and function, at times, as the introduction to substantial letters. The reader thus now has the opportunity to perceive some letters in their entirety and to consider subsequent paragraphs differently because of the potential for restored information at the opening. In other examples, internal passages in the letters, constituting groups of sentences or short phrases, have been restored, these also being marked with the key indicating previous suppression. It would be further helpful for scholarly purposes to have an exact specification of the source(s) for each of the restored passages; this could be supplied via a traditional apparatus. That having been said, scholars must now ask if the newly available parts of these letters yield a different or modified picture — or perhaps new interpretive insights — into the creative personalities of Gustav or Alma Mahler, if not both.

Many of the letters from Gustav to Alma were written during the period of their courtship or during extended times of professional separation after their marriage. These latter periods were inevitably occasioned by Mahler’s duties as conductor, during periods of isolation for composition, or as part of a related professional invitation. As a consequence, Mahler’s voice in this correspondence is divided between lover, husband, composer, conductor, mentor, and reporter of travel anecdotes. Several groups of the letters, taken from representative period of the correspondence, will provide a sense of the topics discussed along with the range of comments dealing with artistic and personal issues.

As a first such group, Gustav Mahler’s letters written to Alma during December 1901 — several months before their marriage — will show some of the modifications offered in the present edition. At the time Mahler had traveled to Berlin for a performance of his Fourth Symphony. A letter written to Alma on 14 December had — in previous critical editions — given rise to some concern on exact dating, since Mahler had inscribed the letter “15 December.” Beaumont’s edition confirms the dating of 14 December, proposed earlier by Mitchell and Creighton. In a subsequent letter from this Berlin sojourn [16 December 1901], Gustav Mahler’s explanation of his “flippant tone” in a previous missive to Alma has now been restored in Beaumont’s edition. This letter shows the effect of including, at both the start of the letter and within the body of the text, several substantial passages that had been stricken from the text as it appeared in previous editions. Again, the supposition of a correction to the dating is here affirmed [Mahler had written incorrectly 17 December 1901]; further, the lengthy first paragraph and a later, similar insert establish continuity and demonstrate a typical surge from personal to aesthetic before returning to the topic of a planned rendezvous, all within the text of one letter. Gustav Mahler’s attempt in the restored first paragraph to account for his flippancy was occasioned by Alma’s epistolary references to another man. Mahler explains in this newly available paragraph that she simply did not understand his tone — as related in print — and that she would have appreciated his jovial attempts to “educate” her, had they been physically together. He concludes this paragraph by glossing over a previous disgruntled attitude and referring to a future bliss in common. In the second paragraph, which had appeared in print previously, Mahler refers to his work and public opinion on the same; he cautions Alma not to respond to other, uninformed views — especially those of his detractors in Vienna, who surely did not understand his art. When read after the first, restored paragraph, the tone of the mentor continues logically between topics — personal and professional, emotional and aesthetic — so that the second paragraph does not bear as unmotivated a tone. Likewise, a later, restored paragraph in this letter elaborates on their planned reunion once Mahler had returned to Vienna. Alma had apparently suggested that he visit her immediately upon arrival; in the newly edited version, Mahler pleads “administrative duties” that would distract him from emotional concentration, if he did not settle these first before visiting Alma. Without this paragraph the earlier version of the letter depicts Mahler as an urgent suitor who relies on his beloved to prepare her family for their relationship on the basis of his falsely presumed accessibility.

During a similar series of communications in September and October 1903 Gustav Mahler commented to Alma on leading artistic figures in Vienna as well as his visit to Amsterdam to conduct the Concertgebouw Orchestra in performances of his Third Symphony. In a previously unpublished letter to Alma, inscribed “Vienna, 4 September 1903,” Mahler declares that he has “absolutely nothing to report.” After complaining of headaches and personal anxiety, he goes on to speak of decisive figures at the Hofoper: Alfred Roller and Anna von Mildenburg are discussed along with a visiting tenor who must be accommodated. Since this letter is now, for the first time, available, scholars have further evidence of the hectic parade of notables regularly accompanying Mahler’s duties at the opera. In the following month Mahler traveled via Frankfurt to Amsterdam. On a postcard depicting Goethe and his parents — now published in Beaumont’s edition — Mahler writes of a similar journey with Alma during the previous year and his wish to travel with her again. The following letters from Amsterdam compliment Willem Mengelberg’s kindness and the astounding preparedness of the Concertgebouw Orchestra which Mahler was rehearsing for performances of his Third. Although Mahler appreciated Mengelberg’s domestic hospitality, he suggests to Alma that they lodge at a hotel, should they visit Amsterdam as a couple in the future. Aside from objecting to restrictions on his freedom, Mahler seems to have revised his opinion — as witnessed in passages here restored — on a possible relocaton to Holland after eventual retirement. Finally, in a brief yet significant aside (previously deleted), Mahler confides to Alma in the letter of 20 October 1903 that the Concertgebouw Orchestra was intent on performing all of his symphonies up to that time. Although the comment is not equivalent to evidence of a contract, the inspiration of hope is clear. Such newly added details show that Mahler’s reputation and appreciation of his creativity was gaining in international circles, despite his complaints to Alma — less than two years before — of being misunderstood in his chosen home environment of Vienna. Surely these additions make the revised version of the letters from Gustav to Alma Mahler a significant source for further scholarship on the composer, his creativity, and the productive relationship between two individuals which helped shape the course of modern music.

Salvatore Calomino

Madison, Wisconsin

January 22, 2007

"Rusalka, la ninfa che è in noi"

Gianandrea Noseda debutta mercoledì a Torino come direttore principale nel capolavoro di Dvorak

Gianandrea Noseda debutta mercoledì a Torino come direttore principale nel capolavoro di Dvorak

"La storia tragica e lieve di una donna incompresa e perdente con una musica fatta di acqua, terra e favole"

Sandro Cappelletto [La Stampa, 22 January 2007]

Ondina, figlia dello Spirito dell’acqua, però decisa - quale errore! - a diventare donna e conoscere gli abbandoni, i tradimenti, le tristezze degli amori tra esseri umani. Rusalka, capolavoro teatrale di Antonin Dvorak debutta mercoledì al Teatro Regio. C’è voluto più di un secolo perchè questa «favola lirica», lieve come un racconto di fate, aspra come un dramma, trovasse, finalmente, la strada di Torino. Sul podio Gianandrea Noseda, 42 anni, al suo debutto come direttore principale del Teatro, dove ha già lavorato per un Don Giovanni salvato in buona parte dalla sua direzione.

Ovation pour le "Don Giovanni" mis en scène par Haneke

Marie-Aude Roux [Le Monde, 22 January 2007]

Marie-Aude Roux [Le Monde, 22 January 2007]

Le Don Giovanni de Mozart, monté la saison dernière au Palais Garnier dans la mise en scène du cinéaste allemand, Michael Haneke, allait-elle supporter la transposition d'une reprise sur le grand plateau de l'Opéra Bastille ? La réponse est scénographiquement positive tant le dispositif de Haneke, qui a situé le drame mozartien dans les grandes tours de La Défense, prend ici tout son sens, soit une féroce âpreté dans un monde sans âme. Haneke a effacé toute légèreté et facétie pour verser du côté de la tragédie classique.

In Austin, Echoes of a Distant War in an Opera’s American Premiere

By STEVE SMITH [NY Times, 22 January 2007]

By STEVE SMITH [NY Times, 22 January 2007]

AUSTIN, Tex., Jan. 20 — The state capital of Texas takes great pride in a live music scene that cherishes tradition while also valuing innovation. The city is a hotbed of both roots music and experimental rock; classical music, by comparison, claims a considerably smaller share of attention. Austin Lyric Opera has long been overshadowed by older, larger, better-financed companies in Dallas and Houston.

January 21, 2007

A Tenor Cashes in on His Money Notes

By MATTHEW GUREWITSCH [NY Times, 21 January 2007]

By MATTHEW GUREWITSCH [NY Times, 21 January 2007]

IT’S ancient history, but the Sicilian tenor Marcello Giordani makes it a point of honor to acknowledge the crisis. His career got off to a promising start in Spoleto, Italy, with Verdi’s “Rigoletto” in 1986. He was 23, and he had plenty going for him: musicality, easy high notes, a handsome face, a good physique. And he was tall — a godsend to leading ladies.

Lebanon's Christine Brewer is respected for her voice, admired for her personality

By Sarah Bryan Miller [St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 21 January 2007]

By Sarah Bryan Miller [St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 21 January 2007]

Soprano Christine Brewer has a voice made for the repertoire of Strauss and

Wagner. She's an international star in the many-are-called-but-few-are-chosen

world of grand opera. In a field noted for justifiable hypochondria, she is

startlingly unfussy about chills, germs and other possible threats to her vocal

health. She's down-to-earth and downright funny. And when she's at home, she

lives a most un-divaish life.

CUYÁS: La Fattucchiera