13 Feb 2007

Dust-bowl opera overwhelming at Minnesota premiere

The great American opera? Ricky Ian Gordon’s “Grapes of Wrath” might be it.

Anthony Minghella's visually-arresting staging, a co-production with New York's Metropolitan Opera and the Lithuanian National Opera, returned this month to its original home at the London Coliseum after a gap of two years.

While I eagerly seized upon an opportunity to hear Angelika Kirschlager live for the first time, having written in very recent weeks about not one but two of the star mezzo’s current CD releases, I ventured to Frankfurt’s Alte Oper feeling a little bit like her stalker.

When I worked in the Archives of the Met, I was custodian of several hundred costumes, many from the days when divas traveled with steamer trunks full of things run up just for them, by the finest designers, with the most glamorous materials, in the colors and styles that suited the ladies themselves.

There is nothing redeeming about Sir John Falstaff, one of Shakespeare’s most lively comic characters and the subject of Verdi’s final opera, and yet, inexplicably, we love him.

What constitutes an “international opera star” these days, anyway?

The Metropolitan Opera audience loves its Wagner, and the management for the last several decades has, alas, made sure we aren’t spoiled: it’s a rare season that gets more than two production revivals of Wagner, and some years there have been none.

With her performance of the “Four Last Songs,” ably partnered by Michael Tilson Thomas and his San Francisco Symphony, Deborah Voigt emphatically confirmed her place as one of the glories of the current roster of Strauss interpreters.

John Adams, whose opera Nixon in China set the bar for post-minimalism in the lyric theatre, has once again scored a success with his latest work.

Wagner’s all-conquering chic made apocalyptic music-dramas drawn from folklore the ideal of the nationalistic era; every serious opera composer of the time felt obliged to attempt something in that line.

In this country art and politics are rarely bedfellows — strange or otherwise; indeed, it’s seldom that the two meet under the same roof.

Regarded, until the modern vogue for earlier masters, as the senior surviving grand master of opera, Gluck never quite becomes fashionable and never quite vanishes.

There is no middle ground in War and Peace — or, rather, it’s all middle ground, like a battlefield, and you may feel as if every soldier in Russia (and in France) has marched over you.

Once upon a time, we used to only dream about a stellar pairing like Barcelona’s Gran Teatre del Liceu has fielded for their current offering on display: “La Cenerentola.”

Enough ink was spilled last year gushing over Valencia’s new Calatrava-designed opera house and Arts and Science park that I had been chomping at the bit for the opportunity to take in a performance there as soon as my availability and, more important, the availability of a still-very-hard-to-find ticket coincided.

Do we too easily take Richard Strauss for granted? The question is prompted by the superlative production of “Frau ohne Schatten” that was the highlight of the fall season at the Chicago Lyric Opera.

Watching The Queen of Spades staged by a Russian company is often an unforgettable experience.

If Belfast in Northern Ireland isn’t a city that immediately springs to mind as a centre of musical excellence then it’s not for want of talent, initiative and professionalism within its cultural community.

After the triumph of his fifth opera, Ernani, Verdi could have gone on writing howling melodramas and made a mint.

Not long ago, English National Opera declared an intention to capitalise on its name and history by placing greater emphasis on English works.

Despite 19th-century Russia’s reputation as an Italian opera haven, Verdi’s late masterpiece Otello found acceptance there only with great difficulty, even though in its 1889 premiere the title role acquired a great local interpreter in the Mariinsky Theater primo uomo, Nikolai Figner.

The great American opera? Ricky Ian Gordon’s “Grapes of Wrath” might be it.

Although opera buffs were sufficiently curious to sell out all five performances of the work premiered by Minnesota Opera on February 10, they nonetheless found it difficult to imagine John Steinbeck’s account of the exodus from the Oklahoma Dust Bowl as an opera.

The 1939 novel seemed too long, too complex and too freighted with despair for such transformation. And doubts were enhanced by reports that identified Gordon with Broadway and Sondheim.

Wasn’t this a task for a heavy-weight composer?

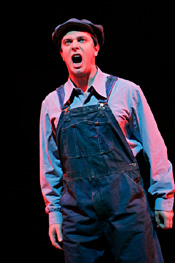

But during rehearsals of “GOW” at St. Paul’s Ordway Center for the Performing Arts, word got around that Brian Leerhuber, Tom Joad in the huge cast, had called the new opera “Verdi on steroids.”

And at the premiere that assessment was wondrously born out by Gordon’s amazing and unusual score, for “GOW” — the composer’s first large-scale work — is of monumental dimensions. With two intermissions it runs over 4 hours, and it calls for 13 principal singers, plus 50 featured roles, several sung by one vocalist.

In three acts divided into 33 scenes, “GOW” is of epic sweep and of a mesmerizing grandeur that makes the audience participants in the Joads’ flight from Oklahoma to California in the depth of the Great Depression.

“GOW” is the product of a collective of gifted artists assembled by MO artistic director Dale Johnson. Librettist Michael Korie has stripped down Steinbeck’s 600 pages to a lean and singable text in verse that only occasionally rhymes and retains the speech patterns of the Okies.

Stage director and dramaturg Eric Simonson, a member of Chicago’s Steppenwolf Theatre for 20 years, has directed, adapted and acted in numerous plays, including Frank Galati’s stage version of “Grapes of Wrath,” in which he played eight minor roles in the production seen both in London and Chicago.

“I was in on the opera from the start,” says Simonson, who recalls “batting around ideas” with Johnson back in 1996. And, working closely with Gordon and Korie, he was a “hands-on” participant in “GOW” as a work in progress.

“Others had sought permission to make an opera of the novel from the Steinbeck estate,” he says,

“but we were the first to whom it was granted.”

“Others had sought permission to make an opera of the novel from the Steinbeck estate,” he says,

“but we were the first to whom it was granted.”

“It was then a matter of whittling the book down to a manageable libretto. We decided to focus on Tom Joad and his mother.”

“Once that decision was made, everything fell into place. Everything else was unessential.”

For the sets - a steel catwalk frames the stage - designer Allen Moyer sought inspiration in Walker Evans’ photographic documentation of the Depression. Projections on the back wall of the stage - sometimes black and white, sometimes motion picture excerpts - add to the dramatic impact of the staging.

Costumes are the work of Kärin Kopischke; choreographer Doug Varone has added animation to

the action.

Costumes are the work of Kärin Kopischke; choreographer Doug Varone has added animation to

the action.

Early on the creative crew considered making “GOW” an American “Ring” running over several evenings; the idea, however, was abandoned

And although there will be demands that the opera be “shrunk,” it is now the length that the story demands.

The score - without recitative - is song based and many scenes flow easily into the next. Gordon points to models in “Porgy and Bess,” “Street Scene,” “Showboat” and Sondheim, but he has gone beyond them in a score that is original and completely his.

One recognizes, to be sure, art songs, musical comedy, jazz, traditional blues and other references to the music of the time of the novel, but the composer has assimilated these influences and washed over them with a style essentially contemporary.

“I want the opera to be a powerful evocation of Steinbeck’s story,” Gordon says in an essay written for the premiere, “a story about great flat distances, wide open spaces, vast silences filled with doubt, fear and hope, with pain and loss and ultimately with compassion and human kindness.

“The wide-open spaces of Copland are in it — filtered through me.”

About the score Leerhuber says that Gordon “gives us lines to sing that soar and tunes that are immediate in their expressive outpouring; it is emotionally gripping music that moves you.”

The mammoth cast is without a weak link. Leerhuber - happily free of references to Henry Fonda’s 1940 movie portrayal, is a strong and sensitive Tom Joad, the son who hopes to help his mother — mezzo Deanne Meek — hold the family together.

Tenor Roger Honeywell is lapsed preacher Jim Casy, and baritone Andrew Wilkowske is moving as retarded son Noah, whose suicide by drowning is expanded from the novel to conclude Act Two.

A gem of the score is baritone Robert Orth’s funereal “Little Dead Moses,” with which he angry — but tenderly — sets Rosasharn’s still-born baby afloat on the river.

Yet it is Kelly Kaduce who tops her many colleagues as downtrodden adolescent Rosasharn (Rose of Sharon). As in the novel — something beyond Hollywood in 1940 — she offers her breast to a starving man and then sings the concluding “One Star,” which “like a candle in a dust storm” will one day “fill the sky with silver sparkles.”

Thus — despite the darkness and overt tragedy of their story — Gordon and Korie lower the curtain with hope.

“GOW,” in sum, is not about the Okies; it is the Okies, these “tumbleweeds on the road to nowhere,” as Korie says, confronted head on. Their story is not told; it is lived out with compelling immediacy before the eyes of the audience, who make the journey with them.

And this it is that places “GOW” in the company of Janáček and Shostakovich’s “Lady Macbeth.”

Almost a century after Mahler’s quintessential score, Gordon and Korie have created a new — and American — song of the earth.

Tom Joad sums it all up at the conclusion of Act Two:

This red land — is us.

All its hardship — is us.

And the flood years.

And the drought years.

And the dust years — all us.

Till we find a place to live,

A home for us to stay,

Our home is here we are,

‘cause us — is USA.

“It’s the story of a disenfranchised people,” says Brian Leerhuber. “And Americans today are struggling with very similar issues of physical and emotional displacement, trying to figure out what the American dream is all about.”

“Grapes of Wrath,” a co-commission of Minnesota Opera and Utah Symphony & Opera, will be on staged in Salt Lake City in May. It will be seen later at Pittsburgh Opera and Houston Grand Opera. Tulsa Opera was considering the work to mark the centennial of Oklahoma statehood in 2007; however, the company’s board of directors, wishing to distance itself from the theme of Okies and the Dust Bowl, vetoed the idea.

Footnote: Since apocalyptic thinking is vogue in certain circles today, it is recalled that Steinbeck’s title comes from the Book of Revelations, Chapter 14, where — in anticipation of the Apocalypse — the grapes in question are pressed.

Ricky Ian Gordon’s latest compact disc is “Orpehus & Euridice,” a song cycle on the world’s oldest love story, premiered on the American Songbook and New Visions series in 2005. Commissioned by Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, the Ghostlight Records release features soprano Elizabeth Futral, clarinetist Todd Palmer and pianist Melvin Chen.

Wes Blomster