March 31, 2007

Operatic flim-flam fun

Alan Conter [Globe and Mail, 31 March 2007]

Alan Conter [Globe and Mail, 31 March 2007]

It would have been pretty nigh impossible for the Atelier lyrique of L'Opéra de Montréal to match the stunning brilliance of last year's production of Benjamin Britten's The Turn of the Screw. Probably best, then, that the company decided to go "light" this year with Joseph Haydn's delightful confection Il Mondo della luna, composed in 1777 for the wedding of Count Nicolaus Esterhazy.

Lyric Opera unmasks new 'Ballo'

By Jeremy Eichler [Boston Globe, 31 March 2007]

By Jeremy Eichler [Boston Globe, 31 March 2007]

All hail Riccardo, Governor of Boston!

Er, which governor was that?

Colonial Boston surely seems light years away from the world of 19th-century Italian opera, but that was precisely the point when Verdi and his librettist, Antonio Somma, chose to appease the nervous censors of Rome by transporting their opera of political intrigue and regicide -- "Un Ballo in Maschera" -- to some place far from European shores. The place they chose was late 17th-century Boston, turning King Gustavus III of Sweden into Governor Riccardo.

Tote Diana, irrer George

Walter Weidringer [Die Presse, 30 March 2007]

Walter Weidringer [Die Presse, 30 March 2007]

London, 1810: König George III. beginnt, stundenlang „mit den Engeln“ zu sprechen, gibt Vögeln Gesangsunterricht, hält einen Baum für den König von Preußen. Schließlich erholt er sich nicht mehr und bleibt die letzten zehn Jahre seines Lebens regierungsunfähig.

March 30, 2007

José Carreras Collection

That would have been, of course, José Carreras, and ironically enough, he was the very reason for the “Three Tenors,” an event at least partly built around the celebration of the singer’s return to health after a frightening bout with leukemia.

Beloved before his illness for his handsome persona and beautiful timbre, with his survival Carreras meant even more to his core audience. As an acknowledgement of that devotion, ArtHaus Musik has boxed 6 DVDs as the “José Carreras Collection.” Many of his fans will have these titles in earlier media incarnations, but they may not be able to resist the call of the attractive packaging.

Before going into a few specifics about each title, a gentle declaration must come first - purely as singing, much of what Carreras produces in these concert appearances cannot match the standard he set for himself before the onset of his illness. In the middle range, some reminder of his appeal comes through. Too often he seems to force the tone, and if he lightens it too much, a wavery effect results. The top, unsurprisingly, fares poorest - often hoarse, sometimes painfully so. It is a tribute to the bond Carreras formed with audiences that he still manages to captivate them, and they give of their love unstintingly.

The ovation that greets Carreras in The Vienna Comeback has to touch one’s heart. He chose a fairly challenging program, in French, Spanish, and Italian, even ending the encores in Swedish for Grieg’s “Jeg elkser dig.” That was in September 1988. About a year later in Salzburg he offered a recital with some of the same selections, but the balance had shifted to somewhat lighter fare - more Tosti, some Guastivino, Halffter. Nonetheless, the top is as troublesome as ever. The ecstatic audience couldn‘t care less, insisting on the requisite 5 encores from the tenor.

Carreras only appears once in La Grande Notte a Verona, singing his crowd-pleasing “Granada.” The rest of the program is a gala affair of very variable vocal contributions and amusing reminders of late 1980s ABBA-influenced hairstyles, male or female. In 1990, Carreras sang a short program of 5 songs and then a “modern” mass setting called “Misa Criolla” from composer Ariel Ramirez. Lightly scored and sweetly melodic, this insubstantial piece poses no great challenge for Carreras, and able to relax, he delivers a pleasant performance.

The strangest of the 6 DVDs is A Bolshoi Opera Night. According to the booklet and credits, Carreras was a sponsor of this gala charity evening, but not only does he not sing, he does not even appear on stage (unless your reviewer blinked and missed him). Another hit-and-miss affair, as a gala this Bolshoi evening will appeal most to those with a fondness for stars near the end of their careers (Bergonzi, Kraus) and Gorbachev-era Soviet opera stars.

The most pleasing of the six CDs finds Carreras with the woman who in some sense discovered him, Montserrat Caballé. Singing solos and some duets, neither singer can be claimed to be in the best of voice, but their sheer joy in each other’s presence adds much more than a few tight high notes can subtract.

Perhaps as an even greater tribute to this fine tenor, a company can release some the filmed work of his from before his illness, when his voice was at its memorable best. The “José Carreras Collection” is for the most devoted fans.

Chris Mullins

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Carreras_collection.png image_description=José Carreras Collection product=yes product_title=José Carreras Collection product_by=José Carreras - Vienna Comeback Recital, 1988 (101 401)José Carreras - La Grande Notte a Verona 1988 (101 403)

José Carreras - A Bolshoi Opera Night, 1989 (101 409)

José Carreras & Montserrat Caballé (101 413)

José Carreras - Salzburg Recital, 1989 (101 411)

José Carreras - Misa Crolla, 1990 (101 405) product_id=ArtHaus Musik 101 417 [6DVDs] price=$92.99 product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/album.jsp?album_id=143883

HANDEL: Poro, Re dell’Indie

It was completed and performed in 1731, in a typically fecund period of his life, being squeezed in between the light-hearted “Partenope” and the rather less obviously endearing “Ezio”. After 16 performances and a couple of quick revivals, that was it until the German exploration of the canon in the first half of the 20th century.

In the current boom years (as they must surely be called) for baroque opera, “Poro” has not been at the top of the agenda for most directors or conductors. Musically it has some fine arias and duets, but it suffers from a clunky plot with holes as large as a Mughal elephant’s foot. The characterisations can be laughable – literally – and even the most intricate and melodic of Handel’s compositions cannot save it from a kind of dramatic purgatory.

The libretto, adapted from Metastasio’s “Alessandro nell’Indie”, centres around a love-triangle taken from an actual event in recorded history. Alexander the Great in his march east defeats and captures an Indian king, Poro. Poro’s beloved, Queen Cleofide of a neighbouring Indian kingdom, seeks to help Poro by pretending to love the invader….and thus sets in motion a web of jealousy, mistaken identity and the usual Handelian sub-plot of secondary lovers (not in the recorded history) caught up in the spokes of confusion that surround the main protagonists.

In his day, Handel was happy to ignore any lack of dramatic cohesion because he knew he could rely on his own brilliance, and that of his three top-flight singers, to distract the ear and eye. The title role was created for, and by, the legendary alto castrato Senesino, that of Alessandro for the remarkable Italian tenor Annibale Pio Fabri, and the prima donna role of Cleofide for Anna Strada del Pò. And to this day the success of this opera depends absolutely upon the quality of the singing – and the modern day director has to rise to the considerable challenge of overcoming the dramatic shortcomings.

This production for the London Handel Festival, featuring young opera singers from the UK on the cusp of professional careers and a fluent, intelligent production by Christopher Cowell, rose to both challenges with aplomb and almost complete success. It was heartening to hear so many fine young voices now singing this repertoire with verve and style, and showing at least the beginnings of true stage awareness – even if nearly all badly needed lessons in deportment. A king or general should stand and look like a king or general, at least in a production that requires “realistic for the age” acting.

The part of Alessandro, part-time conquering hero and (in this production at least) full-time philosopher and marriage-guidance counsellor, was taken by Nathan Vale. This young tenor last year won the Handel Singing Competition from some high class opposition, and was obviously popular with the crowd at this, final, performance in the run. His tenor is very flexible and has an interesting darkness in the timbre that suggests that it may develop into something rather different, given time. His control in the many, many divisions (almost armies) of semi-quavers that his character is blessed with was remarkable. Tonally, he was generally consistent and smooth through the range, although he needs to learn to put more light and shade, more variation of dynamic, into his singing in response to the text; sometimes the machine-gun delivery quite took over from the meaning of the words themselves. But a most satisfying performance – it would be good to hear him in more legato material.

His rival in love and war, Poro, was sung by countertenor Christopher Ainslie and after a slightly shaky start his voice was the one which probably improved most during the evening’s entertainment. He has a strong, well-supported, alto voice with no hoot or wobble and – in contrast to Vale – had plenty of opportunity to display his natural ease and skill with the more poignant and reflective arias that Handel wrote for the master of that genre in the 1730’s. His acting skills were to be applauded too – he managed to find a number of ways to continually display jealousy without succumbing to routine.

The focus of both men’s attention as Queen Cleofide was Ruby Hughes, a young soprano with considerable gifts. She has a warm, expressive and easy soprano that gave promise of some weight and power to come, and of all the singers perhaps gave the most finished performance. Articulation, intonation, colour and dynamic were all there, and she has an attractive stage presence. Again, like the other young singers, she could benefit from some intensive “how to walk and stand” training, but that is easily fixed, and no doubt will be.

The more minor roles were taken by bass Hakan Ekenas (Timagene) of whom one wished for more in the way of arias as his voice was very appealing, and sounded quite at home in the idiom; mezzo Madeleine Pierard (Erissena) who, like Ainslie, grew in stature through the evening but lacked slightly in consistency; and countertenor Andrew Pickett (Gandarte) who had expressive moments but struggled a little with the recitatives in particular.

Although this opera tends to the London Bus style of format, (there’s always another da capo aria coming along behind), it is thankfully interspersed with some wonderful duets and ensembles – of which the Act Two “Caro amico amplesso” between Poro and Cleofide is an example. It wasn’t actually included in the Metastasio libretto but Handel decided to transplant it here from his “Aci, Galatea e Polifemo” – and all the better for it. Ainslie and Hughes’ work together here was delicious.

Throughout, Laurence Cummings kept the augmented London Handel Orchestra on its toes and allowed no unnecessary lingering – a good idea with this piece. As ever they were very stylish, and also rather less astringent than I have heard them, with some neat work from the flute and oboes in particular.

The production itself was in the “elegant but inexpensive” category, the costumes of old India and some vaguely 18th military gear for the Greeks supplying most of the vibrant colour and sparkle whilst the simple backdrop of gauzes were lit appropriately as the story progressed. A single hanging metre of vivid blue silk depicted the River Hidaspes, which divides the opposing camps, and with the exception of the odd cut-out tree and tea-chest, that was about it. But it worked. Cowell managed to get across the idea – one which Handel espouses in the music – of a meeting of cultures with mutual respect for each other. If there was a problem it was of our own making, in that the incredibly understanding, generous and fair-minded Alessandro was just too good to be true and we laughed. In 1731, I suspect, Handel’s audience would have been impressed and satisfied that those in power should show such noble and selfless ideals – it did rather remind us of how cynical we have become.

© Sue Loder 2007

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Poro_RCM.png image_description=G. F. Handel: Poro, Re dell’Indie (Royal College of Music - 2007) product=yes product_title=G. F. Handel: Poro, Re dell’Indie product_by=30th London Handel FestivalRoyal College of Music, 28 March 2007 product_id=ABOVE: Christopher Ainslie and Nathan Vale (Photo courtesy of RCM)

March 28, 2007

Camacho’s Wedding (Die Hochzeit des Camacho)

There is unquestionably a need for a company such as this on London’s operatic scene; they continue to fly the flag for works which would not otherwise be performed, and are almost unique in offering these obscure works in staged performance rather than in concert.

The company exists independently of the academic functions of University College London, which does not even have a music department; instead the company draws its large and enthusiastic amateur chorus, orchestra and lesser principals from the University College Union Music Society, and hires in young professional artists for the leading roles – alumni include Felicity Lott, Robert Lloyd and Jonathan Summers, and Charles Mackerras served briefly as Musical Director during the 1950s.

Die Hochzeit des Camacho was written by Mendelssohn between the ages of fourteen and sixteen. It is a lively, folksy comic opera based on an episode from Don Quixote, about a conspiracy on the part of the young and amiable Basilio to save his beloved Quiteria from a forced marriage to the wealthy but unprepossessing Camacho. After many complications, some largely pointless interventions by Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, and a faked suicide, Basilio gets the girl; her father and Camacho accept their union and all live happily ever after.

The production, by Duncan McFarland, was set in the context of a bedtime story being told to a young boy (Oliver Kirk) by his nurse (Liz Lea). This gave the feel of a cosy Christmas family movie. Christopher Giles’s set was simple but imaginative and versatile, with three brightly-coloured moving wooden huts transforming the stage from the child’s nursery into all manner of different locations. There were bright, attractive costumes for the young cast too.

The opera was sung in English, and the best individual performances came from two fine tenors – medical student Hal Brindley gave a strongly sung and charming account of Basilio’s sidekick Vivaldo, while postgraduate linguist James Crawford gave an excellent characterisation of the eponymous Camacho (really quite a minor role). Stephen Brown’s Basilio and James Harrison’s Carrasco (Quiteria’s father) also sang well; Håkan Vramsmo’s Sancho Panza was likeable and smoothly sung. But elsewhere there were problems; Margaret Cooper’s Quiteria was strong in the upper register but weak in the middle; her conventionally operatic soprano was inadequately balanced by Sarah Rea’s treble-like Lucinde. The veteran professional bass Deryck Hamon was seriously stretched in the role of Don Quixote. Projection of dialogue was problematic for professional and amateur soloists alike; sometimes the singing was inaudible too. The chorus was excellent, but the biggest problem was the orchestra, an amateur ensemble, whose timing and tuning were simply painful at times despite Charles Peebles’s poised and well-phrased direction.

This is the fifth UC Opera production I have seen, some with high musical standards. This was far from the best. Perhaps they will fare better in 2008 with Lalo’s Fiesque.

Ruth Elleson © 2007

image=http://www.operatoday.com/mendelssohn.png image_description=Felix Mendelssohn product=yes product_title=Camacho’s Wedding (Die Hochzeit des Camacho) product_by=University College OperaBloomsbury Theatre, London, 21 March 2007

March 27, 2007

Deutsche Oper Goes From Bad to Worse With Weber Booed in Berlin

By Shirley Apthorp [Bloomberg.com, 27 March 2007]

By Shirley Apthorp [Bloomberg.com, 27 March 2007]

March 27 (Bloomberg) -- Berlin's Deutsche Oper is in more trouble, with its latest production facing a storm of boos.

Carl Maria von Weber's opera ``Der Freischuetz,'' which opened at the crisis-ridden house on Saturday, could have proved a much-needed crowd-pleaser. Instead, it was a debacle.

Soprano’s Colorful Voice Undimmed, Despite a Cold

(Photo: Tanja Niemann)

(Photo: Tanja Niemann)

By ANNE MIDGETTE [NY Times, 26 March 2007]

Some things are more memorable for their imperfections: the fly in the amber, the lopsidedness in a friend’s smile. Add to this list Diana Damrau’s cold at her recital on Wednesday night at Weill Hall.

BRUCKNER: Lateinische Motetten — Latin Motets

Of the latter, Bruckner composed a number of motets that reflect his nineteenth-century perspective on a sixteenth-century form. Not in the style of the solo motets that French composers of the nineteenth century created for virtuosic singers, nor the accompanied motets that eighteenth-century composers like Mozart wrote for use in church, Bruckner’s motets revivify the vocal polyphony associated with such composers as Josquin and Willaert, albeit with decidedly modern touches, mostly in the sometimes chromatic harmonies that point up the usually traditional texts he chose for these works. With these veritable miniatures, Bruckner offers a vocal contrast to his large-scale instrumental symphonic works.

This selection from Bruckner’s larger body of motets was recorded by the Philharmonia Vocalensemble Stuttgart, conducted by Hans Zanotelli, and with tenor soloist Oly Pfaff; some of the works include organist, Manfred Hug, while others include obligatti trombones, here played by Klaus Bauerle, Peter Redwig, and Fritz Resch. The dates of the recording, as listed with accompanying notes are 6 and 7 April 1979, without further identification of location and circumstances. Nevertheless, this recording makes available a representative selection of Bruckner’s works in this genre, and the performances are uniformly solid.

Those unfamiliar with Bruckner’s vocal music may be aware of his three Masses, which are comparable in scope to the composer’s symphony works. With the motets, Bruckner is working on a contrastingly smaller scale, essentially creating miniatures instead of remaining with the larger canvases associated with his style. Compressed in form and performing forces, the motets are works that do note benefit from the repetition and development of thematic material found in Bruckner’s symphonies and Masses. Instead, these through-composed pieces contain shorter, motivically based lines that sometimes benefit from points of imitation. The ideas seem fleeting, with the various internal cadences serving as points of arrival that define the harmonic idiom that supports these otherwise contrapuntal works.

The first piece in this selection, the unaccompanied motet Pange lingua is a contrapuntal setting of the traditional Easter sequence. It offers modern listeners a denser texture than the monophonic one found with the sequence, and in this piece Bruckner allows the contrapuntal lines to support each phrase of this familiar text. Composed in 1868, just before Bruckner worked on his watershed Third Symphony, this motet is a mature example of his vocal music, and a fine introduction to the pieces collected here. In this performance, the Philharmonia Vocalensemble Stuttgart offers a tight reading of this work, with the voices working together under the direction of Hans Zanotelli. Despite its allegiances with the past, this work reflects its modern sensibilities through the various points of arrival that betray a modern approach to harmony, and not the kind of chromatic idiom that would be the result of employing musica ficta.

While some of the pieces can sound similar, Bruckner sometimes varies the unaccompanied mixed chorus by using different voices, as with Inveni David, for men’s choir, which also stands apart because of the trombone accompaniment used in this piece. The solemn setting of Ecce Sacerdos, a text usually associated with ordination or the installation of a primate, is similarly rich for its use of mixed chorus, trombones and organ, which results in a more varied timbre and fuller texture. While the contrapuntal writing in the latter owes much to the Renaissance models that Bruckner knew, the actual compositions in Bruckner’s hands can be nothing but modern, as the nineteenth-century composer reinvented the style of an earlier era in much the same way that a painter like Makart created historic settings anew with a Romantic eye for forms and color. Just an appreciation of Bruckner’s symphonies can be heightened by knowledge of his Masses, the smaller works, like these motets offer a further glimpse at the composer’s imagination. Given Bruckner’s skill at crafting vocal music effectively, it is no wonder that the chorale-like passages in his symphonies are convincing even in that instrumental milieu. Yet Bruckner’s vocal music is convincing in itself, especially as found in the Latin motets that are found on this recording.

James Zychowicz

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Bruckner_Latin_Motets.png image_description=Anton Bruckner: Lateinische Motetten — Latin Motets product=yes product_title=Anton Bruckner: Lateinische Motetten — Latin Motets product_by=Philharmonia Vocalensemble Stuttgart, Hans Zanotelli, conductor product_id=Profil (Hänssler) PH07002 [CD] price=$15.99 product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/album.jsp?album_id=143952La donna del lago, New York City Opera, New York

By Martin Bernheimer [Financial Times, 26 March 2007]

By Martin Bernheimer [Financial Times, 26 March 2007]

The New York City Opera – relatively poor and historically feisty – languishes forever in the shadow of the mighty Metropolitan. Now it finds itself contemplating a cultural crossroads.

Welcome back noble 'Chenier'

BY RUSSELL PLATT [Newsday, 26 March 2007]

BY RUSSELL PLATT [Newsday, 26 March 2007]

"Andrea Chénier" has come back to the Met, and that's good news. Umberto Giordano's 1896 score - with a well-paced libretto by Luigi Illica, who would go on to do grand work with Puccini - possesses a noble strength and clarity that sets it apart from some of the gaudier efforts of the verismo school.

Julian Budden — BBC producer and Verdi scholar

[Independent, 26 March 2007]

[Independent, 26 March 2007]

As a musicologist Julian Budden was best known for his monumental work The Operas of Verdi, published in three volumes between 1973 and 1985. He worked for the BBC for more than 30 years, as a music producer, chief radio producer of opera and external music organiser. His opera productions on Radio 3 included many Verdi operas, but also such works as Massenet's Cendrillon and Vaughan Williams's Hugh the Drover.

March 26, 2007

Culture clash

Warwick Thompson [ThisIsLondon, 26 March 2007]

Warwick Thompson [ThisIsLondon, 26 March 2007]

Handel's 1731 opera deals with the ancient campaigns of Alexander the Great in 'India', the region now known as Pakistan and Afghanistan. Director Christopher Cowell sets the story in the early 18th century and - without a single tub being thumped - its contemporary relevance is all the greater because of it.

RAMEAU: Platée, Pigmalion, Dardanus Ballet Suites

Although it would be incorrect to assume that the origins of the suite were exclusively French, it is safe to say that the popularity of French ballet in general, and the operas of Jean-Baptiste Lully in particular, led to the creation of the orchestral suite toward the end of the 1600s. These works were initially formed by excerpting dance movements from operatic divertissements and placing an overture at the beginning. Conductor Roy Goodman has revived this practice for a Naxos recording on which ballet suites from three operas by the Jean-Philippe Rameau are drawn. The result is a welcome—if a slightly uneven—addition to the growing body of Rameau’s music recorded on CD. Goodman leads the European Union Baroque Orchestra, an ensemble of young musicians that is assembled each year to give the performers an opportunity to train under the direction of a variety of early music specialists. This CD includes performances by three different ensembles and three different recording sessions dating from 1999 to 2003.

The first suite is taken from Rameau’s witty comedy Platée, about the eponymous swamp nymph who falls in love with Jupiter. This music requires a deft touch that will allow its ironic humor to come through, and in general Goodman and the orchestra succeed in doing so. The overall sound is clear, buoyant and well-balanced, yet in some movements, the playing veers toward the prosaic. For example, in the “Air pour des fous gais et des fous tristes,” the aural depiction of the happy and sad fools would benefit from greater extremes of tempo and articulation. The performance is undeniably graceful and elegant, but this music is essentially parodic and deserves to be treated as such. At the premiere, the dancers, who dressed either as infants or Greek philosophers, were accompanied by the personification of folly playing a lyre that she had stolen from Apollo. The entire episode ridicules various conventions of the operatic stage, both musical and dramatic. Certainly overstatement is in order; the mock seriousness of the sad fools needs magnification, while the music of the happy fools could be much more manic. Especially at the end of this movement—when the two groups of dancers mingle and there are sudden shifts of tempo, dynamics and accent—the sharpest contrast is required.

Likewise, the two suites that follow are convincing by and large, but occasionally include a few sections that sound somewhat perfunctory. In Pigmalion, Goodman and the orchestra artfully maneuver through the rapid changes of meter and tempo that distinguish the movement entitled “Les différents caractères de la danse,” a movement intended to accompany Galatea—the statue brought to life—as Cupid teaches her how to move. Yet later in the same suite the performance starts to falter. Throughout the slow and lyrical “Air gracieux,” the music remains graceful, but lacks the sense of momentum that is heard elsewhere. Similarly, Tambourins III and IV from the Dardanus suite are fast enough but are rhythmically a bit square.

In short, all three suites receive satisfying performances and despite the minor quibbles that I have mentioned, do justice to Rameau and his music. Of course, confirmed fans of Rameau will most likely prefer to seek out complete recordings of the operas excerpted on this CD. Nonetheless, Goodman and the European Union Baroque Orchestra should be commended for making some of the eighteenth-century’s most delightful instrumental music available in a highly affordable and unquestionably pleasing recording.

Michael E. McClellan

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Rameau.png image_description=Jean-Philippe Rameau: Platée, Pigmalion, Dardanus Ballet Suites product=yes product_title=Jean-Philippe Rameau: Platée, Pigmalion, Dardanus Ballet Suites product_by=European Union Baroque Orchestra, Roy Goodman product_id=Naxos 8.557490 [CD] price=$7.99 product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/Drilldown?name_id1=106592&name_role1=1&bcorder=1&comp_id=77881GRÉTRY: Pierre le Grand

So, for no other reason than that, the recent recording of a live performance at Moscow’s Helikon Opera of that composer’s Pierre le Grand is reason to celebrate. Nonetheless, despite a clever production and some respectable singing, this DVD will not entirely satisfy fans of eighteenth-century French comic opera and will serve at best as a curiosity of limited attraction for the general opera lover.

Pierre le Grand is a rather fanciful retelling of Peter the Great’s courtship of his second wife, Catherine. The libretto, by Jean-Nicolas Bouilly, is loosely based on an account written by Voltaire and depicts the Russian emperor as an earnest young man who, disguised as a shipyard carpenter, is living in the seaside community to which the young widow Catherine has retired. Complementing Catherine and Peter is another pair of lovers: Caroline, the daughter of Peter’s employer, and Alexis, a young orphan. The basic action of the three acts (condensed to two in this performance) is quite simple: Catherine and Peter reveal their love for one another in the first act; Peter is called away on an urgent matter of state in the second, leaving Catherine with the mistaken belief that he has deserted her; and in the final act Peter’s true identity is revealed, and the lovers are reunited. Although the story may seem to revolve around affairs of the heart, the fact that Peter is Tsar makes this a political opera. The work was premiered in Paris on 13 January 1790, during the early, idealistic days of the French Revolution when a constitutional monarchy seemed both desirable and likely. Within that context, Peter’s down-to-earth behavior and interest in the lives of his subjects assumed a revolutionary hue made explicit in the final vaudeville, which becomes a prayer for King Louis XVI.

The production on this 2002 Art Haus DVD makes no attempt at period musical performance, but as conductor Sergey Stadler states clearly in an brief interview included in the “extras” included on the disc, that was not the intention. Although purists may long for the lighter sound of historical instruments and vocal performances that are more soft-edged, the Helikon Opera’s performers do acquit themselves satisfactorily. The shortcomings of the production are not the fault of the musicians, but stem from a lack of physical space. The Helikon Opera uses the courtyard of a lovely eighteenth-century residence as their performance venue, but as a result the stage area is severely limited, having a depth of only four meters. Despite an ingenious set design in which wooden scaffolding and canvas serve as a ship, a shipyard, or the interior of house, the action always seems constrained and is visually rather static. This is compensated for, in part, by the adoption of a quick dramatic pace that is achieved through cuts, not to the music, but to the spoken dialogue that separates the musical numbers.

A curious feature of the dialogue in this performance is its blend of Russian and French. Although the principals typically converse in the original French, minor characters frequently speak Russian with a few French phrases thrown in for good measure. Moreover, after an extended French dialogue between principals, another performer will inform the audience of what has just been said in a Russian aside. Similarly, when the stage set is being reorganized to depict a new scene, a character may explain what the new configuration represents. Such self-conscious, meta-theatrical devices abound, but they work well given the intimacy of the theater and the gently ironic tone that characterizes the performance. In short, Helikon Opera’s Pierre le Grand is not likely to foster a revival of Grétry, but it may give aficionados of eighteenth-century opera-comique an inkling of what that underservedly ignored genre is like.

Michael E. McClellan

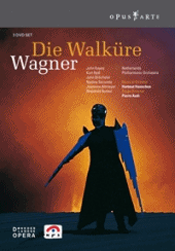

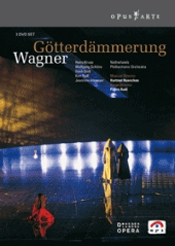

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Peter_the_Great.png image_description=André-Ernest-Modeste Grétry: Pierre le Grand product=yes product_title=André-Ernest-Modeste Grétry: Pierre le Grand product_by=Nikolai Dorozhkin, Anna Grechishkina, Mikhail Davydov, Chorus and Orchestra of the Helikon Opera, Sergey Stadler (cond.). Stage Production: Dimitry Bertmann. Sets and Costumes: Igor Nezhuy and Tatiana Tulubieva. product_id=ArtHaus 101 097 [DVD] price=$19.98 product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/Drilldown?name_id1=4741&name_role1=1&comp_id=151237&bcorder=15&label_id=4357WNO's 'Walkure' Takes Flight

By Tim Page [Washington Post, 26 March 2007]

By Tim Page [Washington Post, 26 March 2007]

There is a very simple reason why the operas of Richard Wagner have become so extraordinarily popular over the past couple of decades, namely, the introduction of projected, line-by-line translations of the words the characters sing as they are performing.

Resurrecting Rossini's Leading Lady

BY GEORGE LOOMIS [NY Sun, 26 March 2007]

BY GEORGE LOOMIS [NY Sun, 26 March 2007]

Under the leadership of its outgoing director, Paul Kellogg, the New York City Opera has made many ventures into repertoire traditionally neglected by New York's major opera houses. But for opera-goers of a certain inclination, none is more important than its investigation of serious operas by Rossini. Three years ago, the company presented "Ermione," another product of the composer's fruitful Neapolitan years, and Thursday evening it offered a stimulating new production of "La donna del lago."

The Modern ‘Magic Flute'

BY STAN SCHWARTZ [NY Sun, 26 March 2007]

BY STAN SCHWARTZ [NY Sun, 26 March 2007]

The house lights fade. The Maestro gives the downbeat, and the auditorium promptly fills with the majestic opening strains of Mozart's "The Magic Flute." Two minutes in, however, just as the music quickens to the lively tempo of the overture's main theme, squiggly lines materialize within the black limbo space of the stage.

March 25, 2007

Chicago Opera Theater springs forward

(Photo: Lisa Kohler)

(Photo: Lisa Kohler)

Company on a roll as it begins season with 'Return of Ulysses'

BY LAURA EMERICK [Chicago Sun-Times, 25 March 2007]

When composer John Adams deliberated over where the first fully staged U.S. version of "A Flowering Tree," his latest opera, would truly blossom, the usual prospects didn't arise.

VERDI: Rigoletto

Music by Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901). Libretto by Francesco Maria Piave after Victor Hugo’s play Le roi s’amuse.

First Performance: 11 March 1851, Teatro La Fenice, Venice.

| Principal Characters: | |

| The Duke of Mantua | Tenor |

| Rigoletto, his court jester | Baritone |

| Gilda, Rigoletto’s daughter | Soprano |

| Sparafucile, a hired assassin | Bass |

| Maddalena, his sister | Contralto |

| Giovanna, Gilda’s duenna | Soprano |

| Count Monterone | Bass |

| Marullo, a nobleman | Baritone |

| Borsa, a courtier | Tenor |

| Count Ceprano | Bass |

| Countess Ceprano | Mezzo-Soprano |

| Court Usher | Bass |

| Page | Mezzo-Soprano |

Setting: Mantua and vicinity in the Sixteenth Century.

Synopsis:

Act I

Scene 1: A room in the palace.

The Duke has seen an unknown beauty in the church and desires to possess her. He also pays court to the Countess Ceprano. Rigoletto, the hunchbacked jester of the Duke, mocks the husbands of the ladies to whom the Duke is paying attention, and advises the Duke to get rid of them by prison or death. The noblemen resolve to take vengeance on Rigoletto, especially Count Monterone, whose daughter the Duke had dishonoured. Monterone curses the Duke and Rigoletto.

Scene 2: A street; half of the stage, divided by a wall, is occupied by the courtyard of Rigoletto's house.

Thinking of the curse, the jester approaches and is accosted by the bandit Sparafucile, who offers his services. Rigoletto contemplates the similarities between the two of them - Sparafucile uses his sword, Rigoletto his tongue and wits to fight. The hunchback opens a door in the wall and visits his daughter Gilda, whom he is concealing from the prince and the rest of the city. She does not know her father's occupation and, as he has forbidden her to appear in public, she has been nowhere except to church. When Rigoletto has gone the Duke enters, hearing Gilda confess to her nurse Giovanna that she feels guilty for not having told her father about a student she had met at the church, but that she would love him more if he were poor. Just as she declares her love, the Duke enters, overjoyed, convincing Gilda of his love, though she resists at first. When she asks for his name, he hesitantly calls himself Gualtier Maldé. Steps are overheard and, fearing that her father has returned, Gilda sends the Duke away after they quickly repeat their love vows to each other. Later, the hostile noblemen seeing her at the wall, believe her to be the mistress of the jester. They abduct her, and when Rigoletto arrives they inform him they have abducted the Countess Ceprano, and with this idea he assists them in their arrangements. Too late Rigoletto realises that he has been duped and, collapsing, remembers the curse.

Act II

The Duke hears that Gilda has been abducted. The noblemen inform him that they have captured Rigoletto's mistress and by their description he recognises Gilda. She is in the palace, and he hastens to see her, declaring that at last, she will know the truth and that he would give up his wealth and position for her who had first inspired him to really love. The noblemen, at first perplexed by the Duke's strange excitement, now make sport of Rigoletto. He tries to find Gilda by singing, and as he fears she may fall into the hands of the Duke, at last acknowledges that she is his daughter, to general astonishment. Gilda arrives and begs her father to send the people away, and acknowledges to him the shame she feels of finding out his profession. The act ends with Rigoletto's oath of vengeance against his master.

Act III

A street. The half of the stage shows the house of Sparafucile, with two rooms, one above the other, open to the view of the audience. Rigoletto enters with Gilda, who still loves the prince. Rigoletto shows her the Duke in the house of the bandit amusing himself with Sparafucile's sister Maddalena, half-drunk in despair over losing Gilda. The Duke then sings the most famous aria of the opera, La donna e mobile, explaining the indifelty and fickle nature of women. Rigoletto bargains with the bandit, who is ready to murder his guest, whom he does not know, for money. Rigoletto orders his daughter to put on man's attire and go to Verona, whither he will follow later. Gilda goes, but fears an attack upon the Duke, whom she still loves, despite believing him to be unfaithful. Rigoletto offers the bandit 20 scudi for the death of the Duke. As a thunderstorm is approaching, the Duke determines to remain in the house, and Sparafucile assigns to him the ground floor as sleeping quarters. Gilda returns disguised as a man and hears the bandit promise Maddalena, who begs for the life of the Duke, that if by midnight another can be found to take the Duke's place he will spare his life. Gilda resolves to sacrifice herself for the Duke and enters the house. When Rigoletto arrives with the money he receives from the bandit a corpse wrapped in a bag and rejoices in his triumph. He is about to cast the sack into the river, weighting it with stones, when he hears the voice of the Duke singing a reprise of his bitter aria as he leaves the house. Bewildered, he opens the bag and to his despair discovers the corpse of his daughter, who for a moment revives and declares she is glad to die for her beloved. As she breathes her last, Rigoletto exclaims in horror, "The curse!" which is fulfilled upon both master and servant.

Click here for the complete libretto.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Rigoletto.png image_description=Rigoletto by Larry Moore (http://www.larrymooreillustration.com/) audio=yes first_audio_name=Giuseppe Verdi: RigolettoWindows Media Player first_audio_link=http://www.operatoday.com/Rigoletto1.wax second_audio_name=Giuseppe Verdi: Rigoletto

WinAMP or VLC second_audio_link=http://www.operatoday.com/Rigoletto1.m3u product=yes product_title=Giuseppe Verdi: Rigoletto product_by=Riccardo Stracciari (Rigoletto), Mercedes Capsir (Gilda), Dino Borgioli (Ducca di Mantova), Ernesto Dominici (Sparafucile), Anna Masetti Bassi (Maddalena), Duilio Baronti (Monterone), Orchestra e Coro del teatro alla Scala di Milano, Lorenzo Molajoli (cond.)

Recorded 1930

MOZART: Die Entführung aus dem Serail

Often stereotypes were cleverly turned on their head, with the seraglio-dwellers proving more modern and progressive than their western guests; Selim’s many wives accessorised their (reasonably) traditional Muslim dress with snazzy sunglasses, while the main quartet of lovers were in full period costume.

Each singer was allowed to keep his or her real accent, so there was a very Welsh Osmin, a Mancunian Pedrillo, and Blonde was even written formally into the English translation as an Australian girl. The youth and freshness of the cast allowed for further jokey concessions to the modern world; Pedrillo’s instrument of choice for the serenade was a brightly coloured electric guitar.

The dialogue fell victim to excessive cuts, which meant that the characters (especially Konstanze) remained a little sketchily drawn – and the break for a single interval after “Martern alle Arten” was misplaced.

Musical values were notably high, with energetic and bright conducting from Gary Cooper. Hal Cazalet sang Belmonte with a free, easy tenor which was never under pressure; Joshua Ellicott’s slightly weightier voice was no less attractive and he displayed considerable comic talent as Pedrillo. Elizabeth Donovan found herself taxed by some of Konstanze’s very highest sustained tessitura, but played the role with assurance and serenity; Lorina Gore’s no-nonsense Blonde sang with complete vocal security. Sion Goronwy’s lumbering Osmin had some terrific low notes; physically he towered above the rest of the cast, giving rise to much visual comedy. The ensemble work was excellent.

Richard Jackson’s Selim was a puzzle; there didn’t seem to have been much directorial thought given to his place in the context of the drama, and he was somewhat lacking in stage presence. Otherwise, the dramatic and comic rapport between characters was strong and well-developed.

Mauricio Elloriaga’s set was simple, consisting of shifting panels – ideally designed for maximum versatility in a touring production; the background and costumes were in cheerful candy colours.

Ruth Elleson © 2007

image=http://www.operatoday.com/content/Le_bain_turc_detail_medium.jpg

image_description=Le bain turc by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1862)

product=yes

product_title=Die Entführung aus dem Serail

product_by=English Touring Opera, Hackney Empire Theatre

London, 16 March 2007

Rebel Poet Loses His Heart (and Head)

By ANTHONY TOMMASINI [NY Times, 24 March 2007]

By ANTHONY TOMMASINI [NY Times, 24 March 2007]

Not many singers today face the pressure that Ben Heppner must feel. His lean, burnished and powerful voice makes him the closest the opera world has right now to an ideal Wagnerian heldentenor. The Metropolitan Opera is not alone in counting on Mr. Heppner for “Tristan und Isolde” (which he will sing next season). And he is poised to portray the impossible-to-cast title role in “Siegfried.”

MOZART: Don Giovanni

All the essential elements for a success seem to be in place: a fine cast, a handsome production from Madrid's Teatro Real (updated to pre-WWII Spain), an impassioned performance from conductor and orchestra. Yet the net effect is much less than the sum of its parts. Why?

Attention to detail, at any level, cannot be the fault. Stage director Lluis Pasqual has each singer well into his/her character, and other than the firearms for swords and an occasional bicycle ride, no actions the characters take are removed from those of the libretto's "original intentions," as traditionalists would have it. Both set designer Ezio Frigerio and costume designer Franca Squarciapino have done outstanding work, at the level of a high-budget period film. The stone city walls stand solid, if aged. The amusement park setting for the scenes in the country side around the Don's home look ready to entertain real customers (especially the colorful bumper cars). The costumes, mostly in dark, heavy fabrics with the exception of some touches of color for the females, appear lived-in, and represent this production's view of the "good" people as staid, sheltered folk. This plays right into the dichotomy of the revengers' search for the Don speaking as much to his attraction for them as to the offenses he has committed against them.

And lighting designer Wolfgang von Zeubek should not be slighted, especially with the lovely blue-wash he lays over many scenes.

In a short interview on disc two, Carlos Alvarez says (in Spanish), "I am Don Giovanni." A rather distressing claim, as the Don he portrays in this production leans to the more aggressive, unpleasant side. Boastful, mean-spirited, and not all that attractive, this is not a Don who evokes much audience empathy for his transgressive pursuit of his own pleasure. Despite that, Alvarez definitely has the role down vocally, and one can imagine that in a production with a different interpretation, he could be more charming and seductive.

Lorenzo Regazzo's big-voiced Leporello parallels Alvarez's Don by seeming more grasping, cowardly than usual, and his catalog aria feels like his own boast. Likewise, Masetto, as sung by José Antonio López, doesn't emphasize the innocence of his character. He looks like a "Don-wannabe" in his heavy jacket and cap, a thug who just hasn't had the breaks the Don has. On the other hand, for once Don Ottavio is not a wimp. The excellent José Bros portrays a confident man who never doubts his woman and leads the revengers, rather than tags along.

Maria Bayo's Donna Anna doesn't have the plushness of the role's most esteemed exponents, but her experience and the sweetness of her tone make her very effective. Sonia Gannassi has more shrillness than even the character of Donna Elvira might require. Maria José Moreno's Zerlina is up to the smaller challenge of her role, even while pedalling a bicycle.

Favoring fleet tempos and energetic dynamics, Victor Pablo Pérez leads the fine Madrid orchestra. He and director Pasqual also get interview segments on the second disc.

If Pasqual had a larger message to his production, it evaded this viewer, even with the help of historic newsreel footage played under the final ensemble after the Don's descent to hell (in cold blue light, with Alvarez strangely waving goodbye to the audience). Perhaps only a Madrid audience can truly feel the power of some analogy between the early Franco era and the world of the Don.

This set offers so much that entrances the eye and pleases the ear, it feels wrong to dismiss it. Let it just be said that while the impact the production seems to promise never gets delivered, the effort deserves respect. Any number of traditional productions on DVD might please many a viewer. For those looking for a more successful exponent of the "dangerous Don" angle, go for the Bieto from Barcelona.

Chris Mullins

image=http://www.operatoday.com/OA0958D.png

image_description=Don Giovanni (Teatro Real Madrid)

product=yes

product_title=Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Don Giovanni

product_by=Carlos Álvarez, Alfred Reiter, María Bayo, José Bros, Sonia Ganassi, Lorenzo Regazzo, Antonio López, José Moreno, Chorus and Orchestra of the Teatro Real Madrid Symphony Orchestra and Chorus, Víctor Pablo Pérez (cond.), Lluis Pasqual (stage director).

product_id=OpusArte OA0958D [2DVDs]

price=$39.98

product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/Drilldown?name_id1=8429&name_role1=1&comp_id=2011&genre=33&label_id=4585&bcorder=1956&name_id=57017&name_role=3

Eugene Onegin — English Touring Opera

Director James Conway chose to focus on the opera’s themes of lost opportunity and the contrast between dreams and shattering reality. Joanna Parker’s very simple reflective set gave a wistful, faded beauty to the stage, while the ‘snow’ for the duel scene was formed of a devastated mass of pages torn from Tatiana’s romantic novels. As Tatiana, Amanda Echalaz provided, rightfully, the opera’s emotional core. She knew how the cripplingly shy provincial Tatiana should walk and move; she knew how to update the character by seven years and several steps up the social ladder without losing her original identity. In recent years, Echalaz’s ETO appearances alone have earned her an exciting reputation; from a slightly one-dimensional performer with a hugely promising dramatic voice, she has developed into a versatile artist with impressive depth of interpretation.

Roland Wood, in the title role, gave a more sympathetic interpretation than most; it was clear that his stiffness and propriety were rooted in self-awareness. His tenderness towards Tatiana was obvious from the start; for once I found myself ‘knowing’ Onegin as well as I always feel I ‘know’ Tatiana.

Michael Bracegirdle’s Lensky didn’t seem at ease on stage, and his singing was monochrome and somewhat forced; as Olga, Marie Elliott was also a little stiff without the necessary weight in her lower register. Gremin’s aria should be the centrepiece of the final act, but Geoffrey Moses failed to bring it to life.

At the start there seemed to be a difference of opinion between the musical and dramatic moods; Michael Rosewell’s tempi were brisk from the outset, while the opening scene was dramatically almost over-restrained. This turned out to be a perfect piece of dramaturgical planning; emotion and passion burst into vivid life at the start of the Letter Scene. The chorus, a good size by ETO’s standards, sang and danced stylishly so it was a great shame that they were the chief victims of a catalogue of unnecessary musical cuts.

Ruth Elleson © 2007

image=http://www.operatoday.com/content/pushkin.jpg

image_description=Alexander Pushkin

product=yes

product_title=Eugene Onegin

product_by=English Touring Opera, Hackney Empire Theatre

London, 15 March 2007

Central City vs. Opera Colorado?

By Kyle MacMillan [Denver Post, 24 March 2007]

By Kyle MacMillan [Denver Post, 24 March 2007]

Two opera companies angling for audiences and funds in the same midsized metropolitan area sounds like a perfect formula for a Hatfield-and-McCoy-style feud.

March 21, 2007

Opera star wins "underwear throwing" case

[Reuters, 21 March 2007]

[Reuters, 21 March 2007]

SYDNEY (Reuters) - New Zealand opera star Dame Kiri Te Kanawa, who refused to perform with an Australian singer because his female fans threw underwear at him, on Wednesday won a lawsuit against her for pulling out of the concert.

ROSSINI: Matilde di Shabran

Such. opera semiserie generally have elements of both comedy and pathos. Matilde di Shabran, is unusual in that the pathos is mixed with some dramatic incidents, especially in Act II, but it also has quite a bit of buffoonery. It turned out to be the last light opera he wrote for Italy, although he did write two other such operas (Il viaggio a Rheims and Le Comte Ory) for France a few years later.

The libretto by Giacomo Ferretti was originally very long and complicated, and Rossini soon realized that he could not finish it in time. He turned to his friend, the composer Giovanni Pacini, for help, and Pacini composed something like six numbers. The version given in Rome also included some self-borrowings from earlier operas. Most of these were removed when the work was given in Naples on Jan.21, 1822. But one duet by Pacini apparently remained. This is the cabaletta to the duet between Matilde and Aliprando in Act I (track19—Ah di veder gia parmi), which Pacini later used in his opera Il Corsaro (Rome, 1831), where it was used as the stretta to a terzetto. This terzetto was recorded in its entirety by Opera Rara as part of their CD “Paventa insano”, which consists of excerpts from unusual Mercadante and Pacini works.

After Naples, where it was performed as Bellezza e cuor di ferro, Matilde was given all over Europe under one of its three titles (the third being Corradino). Outside Europe, it was produced in Brazil, Algeria, Mexico, and the U.S. (NYC on Feb. 10, 1834). It continued to be given regularly until around 1850. Florence, however, heard it as late as 1892, after which it disappeared for over 80 years. It’s first post-World War II revival was in Genoa in 1974, when the original 1821 version with Pacini’s additions was given. It vanished again, only to be heard in its revised version in Pesaro in 1996. Bruce Ford was originally scheduled to sing the tenor role, but withdrew, and was replaced by Juan Diego Florez, making an auspicious Italian debut. It was later given in Bad Wildbad, and then for a second time in Pesaro in 2004 with Florez again singing Corradino and Annick Massis as Matilde . It is this performance that is presented by Decca Classics.

The plot has some unusual aspects, featuring a different type of hero, Corradino, who is a combination of petty tyrant and mysoginist. Corradino starts out hating just about everybody, especially women and poets, but winds up getting the girl in the end. She is a bit of a spitfire, with a ready answer for everything. In the finale of Act I, she charms Corradino out of everything except his pants. Other characters include Isidoro, a wacky poet, Aliprando, the castle physician, and Edoardo, the son of Raimondo who owns a neighboring castle and is on bad terms with Corradin, as well as the Contessa d’Arco, who has designs on Corradino herself. The Contessa manages to throw suspicion on our heroine in Act II by claiming that she had freed Edoardo and producing a forged letter. Corradino believes the Countess, sentences Matilde to death by being thrown off a cliff into the raging torrent below, and orders Isidoro to do the dirty deed. Isidoro soon returns to announce that Matilde is dead, after which Edoardo relates that his jailer had been bribed by the Countess to loosen his bonds. Corradino is horrified at the thought of having put to death an innocent woman, when, surprise of surprises, she turns up, very much alive, and all ends well.

The libretto of the revised version has relatively few arias and duets, but an unusually high number of ensembles. Thus, there are four major ensembles: a quartet for male voices, a quintet, a sextet, and a lengthy finale to the second act. Even the “love duet” for Matilde and Corradino, which is a part of the first act finale, becomes a quartet since two of the other characters are hiding behind some columns, and comment on the action. The hero and heroine have only one aria between them, that being Matilde’s rondo finale. On the other hand, Eduardo has two arias (one in each act), Isidoro has one and Aliprando has an extended solo, with the participation of the chorus in the introduction. Corradino did have an aria in the Rome version, but that was removed for Naples since it was a self-borrowing from another Rossini opera.

Both of the principal artists should be fairly familiar to collectors of 19th century operas. Annick Massis has recorded La dame blanche for EMI, several works for Opera Rara, including Meyerbeer’s Margherita d’Anjou, and participated in the previously mentioned CD of Mercadante and Pacini rarities. Juan Diego Florez is the leading exponent of Rossini’s light roles of the day, having also recorded Le Comte Ory and a DVD of the Barber of Seville, as well as several aria recitals. He is regarded by some as the finest tenore leggero of the recorded era, and is gifted with a brilliant top and great ability with coloratura. I am also very much impressed by the basso cantante Marco Vinco, and predict a bright future for him. Other fine relatively new singers in the recording include the mezzo Hadar Halevy who sings Edoardo and the buffo Bruno de Simone, the Isidoro of the recording.

I enjoyed this opera very much, and can recommend it to fans of Rossini and/or bel canto without hesitation.

Tom Kaufman © 2007

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Matilde_di_Shabran.png image_description=Gioachino Rossini: Matilde di Shabran product=yes product_title=Gioachino Rossini: Matilde di Shabran product_by= Annick Massis (Matilde), Juan Diego Florez (Corradino), Prague Chamber Choir Orquesta Sinfónica De Galicia, Riccardo Frizza (cond.) product_id=Decca 475 7688 4 DHO3 [3CDs] price=$49.98 product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/Drilldown?name_id1=10388&name_role1=1&comp_id=86176&genre=33&bcorder=195&label_id=2303DONIZETTI: Roberto Devereux

I’m still searching which small detail director Loy succeeded in highlighting in this modern production that otherwise would have escaped me in a traditional one. It takes less than a minute to realize the ridiculousness of it all. At the royal palace in London cleaners enter with Royal Cleaning Service in bold letters on their uniforms; probably for fear we would otherwise not have caught the originality of the concept. Soon after, all members of Parliament are looking into their own copy of The Sun, England’s popular tabloid well-known for its coverage of royals. Loy had a special edition of The Sun printed telling us on its front page: “Seducer returned” “Devereux is back”. From that moment on the story turns from ridiculous to risible. If one uses telling and realistic details, one asks the audience to accept the rest of the story as really possible as well. Therefore one is asked to believe that modern Parliament can condemn anyone to death and that the actual Queen Elizabeth is able to act without a single member of Her Majesty’s Government to be noted within hundreds of miles — a problem not existing in a traditional production as the real queen Elizabeth I not only reigned but governed as well.

To muddy the waters somewhat more Loy asks his prima donna to remove her red wig at the end revealing a few tufts of grey hair (a wig as well) which is quite compatible with the last days of the real Tudor Queen. This reviewer doesn’t like traditional productions per definition. Update if you want and if it is possible; but do it consequently and put some work in it. That means more than just putting singers in modern dress and having them read The Sun. That means replacing the historical names and even changing the words in the libretto. No modern Sarah, Duchess of Nottingham would dream of referring to Rosamunde (mistress of King Henry II and incidentally another opera by Donizetti) as most members of parliament wouldn’t know whom she was singing about. In a traditional production this is of course wholly acceptable as every nobleman in the 16th Century, and even every Italian opera lover of Donizetti’s time, knew who fair Rosamunde was. But this means new and unfashionably hard work and maybe madame Gruberova would refuse to sing a wholly new text.

Updating means too that one knows how to handle a chorus but the only solution Loy finds during most scenes consists of chorus members and soloists shaking hands and clapping each other on the back in the most dreadful old-fashioned way possible. And when the Duchess hands over the ring which can save Devereux’ life to the queen, this cannot be done standing but has the two ladies crawling as worms on the floor.

As could be expected one of the main Munich papers hailed the production as “an overwhelming chamber play with precise gestures and unflagging dramatic conviction”. Their reviewer probably has the necessary hamburger-mentality this writer lacks. Opera according to one of its modern prophets, one Robert Wilson, has to be savoured as a hamburger; layer for layer and not as a whole. So there needn’t be a straight relation between music, text, surtitles, costumes and sets as long as each element is fine on its own. Mr. Loy is fine apostle of this creed. Moreover, I admit freely he is a great entrepreneur. His productions of Zemlinsky’s Der Zwerg and Hänsel und Gretel which I saw at De Munt and De Vlaamse opera were almost identical. Now that’s the right spirit, cashing in twice for the same idea.

Such a production cannot but diminish the musical aspects which is a sorry thing indeed . Gruberova was 59 at the time of recording (almost the exact age of queen Elizabeth when she had her fling with Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex and stepson of the great love of her life, Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester) and thus she has, probably involuntary, ‘le fysique du role’. She is less than a minute on the scene and she already sings a stunningly beautiful trill. Throughout she is in very good voice — lashing out when necessary and proving her technical mastery with a series of examples of ‘messa di voce’, trills and pearly coloratura. There is no hint of a wobble or breathiness. She, as the saying goes, sings better than most coloraturas twenty years younger. She only betrays her age by the one weakness she always gives in to: no one is clearly able to convince her to renounce a difficult not to be found in the score C or D at the end of a cabaletta, as nowadays these notes are mostly flat and, as a consequence, she somewhat spoils her magnificent arias in the first act and during the final scene.

Tenor Roberto Aronica sings better than I remember from his live performances. His is not the most sensuous sound, but it is a real Italian voice with a good metal core. He sings sensitively with fine diminuendi and good and strong high notes.

Albert Schagidullin has a strong and beautiful bass-baritone, reminding me of the noble sound of young Ettore Bastianini. He too knows how to phrase and it’s probably not his fault his Duke of Nottingham looks rather comic with his modern horse tail hair.

Jeanne Piland has a clear fine mezzo but looks as old as the Queen herself. It’s difficult to believe in Devereux’ passion.

Conductor Friedrich Haider proves his reputation as a singer’s conductor to be true. Everybody is clearly at ease though there is vitality in his reading. He also gives us the full score and that means two verses of the many cabalettas.

The picture quality is very high but there is a problem with synchronizing. No actual date of performance is given. We only learn there were performances on four days in May 2005. This DVD therefore was probably culled from several performances but in the editing things went wrong from time to time as there are several moments where singing and mouth positions do not correspond.

Jan Neckers

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Robert_Devereux_Gruberova.png image_description=Gaetano Donizetti: Roberto Devereux product=yes product_title=Gaetano Donizetti: Roberto Devereux product_by=Edita Gruberova (Elisabetta), Roberto Aronica (roberto), Albert Schagidullin (Nottingham), Jeanne Piland (Sara), Manolito Mario Franz (Cecil), Steven Humes (Gaultiero), Nikolay Borchev (Paggio), Johannes Klama (Giacomo). Bayerische Staatsorchester conducted by Friedrich Haider. Staged by Christof Loy – Video Direction by Brian Large. product_id=Deutsche Grammophon 073 418-5 [DVD] price=$27.98 product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/Drilldown?name_id1=3144&name_role1=1&comp_id=51820&genre=33&bcorder=195&label_id=5813TELEMANN: Komm Geist des Herrn — Late Cantatas

The emphasis on Bach has not yielded a static sense of the cantata, by any means, but I suspect that we have tended to see its dynamic changes within the boundaries of Bach’s career and not much beyond.

The present recording offers a compelling glimpse of the cantata in the years after Bach’s death with three cantatas by Telemann from the late 1750s and early 1760s, works written when Telemann was an old man in his eighties. If an old man, his style here has nevertheless moved with the times. The cantata’s mix of recitative, aria, duet, and chorale shows a degree of continuity with the earlier cantata, but the style, compared to the Bach cantatas, is decidedly different. Telemann’s late cantatas feature line and phrases that are smaller-scale and more focused on small motives; the music is less contrapuntal and arguably simpler. Those who complained of the unnaturalness of Bach may have found in this music a more agreeable vocabulary. And a distinctive difference, as well, is the relatively little amount that the choir is given to do—some chorale verses and a few short movements. The orchestral and vocal lines alike are often intricately ornamental, but it is an intricacy that graces rather than overwhelms.

The strongest link with the earlier and better known Bach works is surely the composer’s engagement of the meaning of the text. Telemann will give melismas of delight in association with words of joy, chromaticism and harmonic alteration for darker words and affections; he will harness the orchestration to special sound effect, as for instance, in the use of timpani where God’s voice thunders from Sinai; and his choral setting depicting an eerily quiet extinguishing of the stars at the Last Judgement is highly atmospheric.

There is much to like in the performances here. Ludger Rémy reveals a fine sense of style and his performers tend to respond in kind. The Telemann Collegium of Michaelstein plays with an infectious buoyance and grace, and the Chamber Choir of Michaelstein, in what little they have to do here, is nicely attuned to that buoyance, as well. Additionally, in their contrapuntal passages, the tidiness of their articulation is a particularly welcome stylistic plus. Of the soloists, both soprano Dorothee Mields and bass Ekkehard Abele are outstanding, with resonant sounds that yet remain focused and flexible, and impressive execution of ornamental sections. The soprano aria “Itzt steigt er” from Er kam, lobsingt ihm is an especially memorable chance to hear Mields’ effortless and alluringly pure tone. Tenor Knut Schoch shares in the articulative grace and focused sound of his colleagues, though on occasion there is a hint of force in the high range. Alto Elisabeth Graf sings expressively, but with an unusual tone, sometimes strident, sometimes forced, and sometimes sounding like unresonant falsetto.

That criticism aside, this is a recording that will amply gratify, both in its stylistic flair and in its exploration of the cantata after Bach. The exploration is a journey well taken, indeed, and Rémy and his forces prove to be congenial guides.

Steven Plank

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Telemann_Late_Cantatas.png image_description=Georg Philipp Telemann: Komm Geist des Herrn: Late Cantatas product=yes product_title=Georg Philipp Telemann: Komm Geist des Herrn — Late Cantatas product_by=Dorothee Mields, soprano; Elisabeth Graf, alto; Knut Schoch, tenor; Ekkehard Abele, bass; Kammerchor Michaelstein; Telemannisches Collegium Michaelstein; Ludger Rémy, Director product_id=CPO 777 064-2 [CD] price=$14.49 product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/Drilldown?name_id1=11975&name_role1=1&genre=90&bcorder=19&comp_id=210865DONIZETTI: Linda di Chamounix

It is one of Donizetti’s best and can easily stand comparison with Bellini’s Sonnambula which has the favours of opera managers. The Donizettean melodies are tuneful, the ensembles impressive and the self-borrowing inconspicuous though for opera lovers acquainted with the same composer’s Maria Stuarda, it can be a shock to meet the impressive Elisabeth and choir scene once more at the end of the first act in Linda di Chamounix. In an interview the conductor of this set reveals the difficulties he had in setting up a concert performance while a theatrical one is almost impossible to get. The main reason seems to be the naïve libretto where the heroine becomes mad and is returned to sanity when she is reunited with her beloved (the same theme as in I Puritani which is regularly performed). I fear the real problem seems to be the sad fact that such a libretto (rich boy loves poor girl, is not allowed to marry her, she gets mad and is cured when his mama relents) doesn’t pass muster with directors as it seems to be old fashioned in their eyes (which it isn’t; think of the horror nowadays in the eyes of parents when their college educated boy would introduce a girl with elementary schooling and no money at all). As a result there are not too many Linda’s on record available and most of them are barbarously cut. Happily this set under review has only a few minor cuts; the major one a cut of only a few minutes in the second act duet between Linda and Carlo and I wonder why that one couldn’t be restored.

The cast is a good one. Indeed, it is even an excellent one though name fanciers will at first shrink back a bit as it seems a bunch of second rate singes were just rounded up to assist the prima donna in a performance on her own label. Though most of the singers didn’t make it to the big league as we can now be sure of 14 years later after the recording was made, they are all worthy performers. Take American tenor Don Bernardini. He is indeed a little bit throaty but the voice is agreeable an manly. He has a fine sense of style and is excellent in his duets where he proves he can embellish his second verses. Finish mezzo Monica Groop will be somewhat better known as an excellent Mozartean and she brings a mellifluous voice to the role of Pierotto and proves that the role is worthy of a good Dorabella. Korean baritone Ettore Kim was not 30 when he recorded his role of Antonio and the sound is attractive and very Italianate. And as he was already singing Jago and Scarpia at the time one wonders if he is not one of those many talented Korean singers who damaged their material by singing too early and too heavy. On this set his fine lyric baritone blends very well with Stefano Palatchi’s firm but charming bass and their duet is sung with elegance and panache. Of course the reason of being of the recording lies with Edita Gruberova and this seems to be one of her best ones. It is probably no coincidence that she chose Friedrich Haider to be the conductor. He is one who allows his prima donna some leeway; not objecting to some interpolated top notes and indeed encouraging her though in the essay accompanying the set he tells that some were eliminated as being not compatible with the preceding music. It is indeed remarkable that none of Gruberova’s lunges beyond high C strikes one as sorely sticking out. She clearly enjoys singing the score and brings her outstanding technique to it, trilling and embellishing wherever it is suitable and in character. Maybe the voice (on record, less in the theatre) has not enough natural vibrato and sounds a bit stiff but this may depend upon personal taste. Anyway the main hit of the opera ‘O luce di quest’anima’ is brilliantly sung and she is equally fine and convincing in the madness scene. Friedrich Haider, one of the few conductors who actually enjoys accompanying singers, brings his love for belcanto and the prima donna to the score though without overly indulging her. His baton never comes to a stand still and his tempi are chosen with a fine eye on the balance between dramatic truth and the singers wishes. [Refer to his fine performance of Roberto Devereux] As there are so few recordings of Linda di Chamounix available this is a worthy addition to the catalogue. The live performance at La Scala with Alfredo Kraus and Margherita Rinaldi is too heavily cut to be a competitor. Only the Devia-Canonici-set is a rival to the Gruberova recording and probably it will be one’s individual liking of the singers that decides which one to purchase.

Jan Neckers

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Linda_di_Chamounix.png image_description=Gaetano Donizetti: Linda di Chamounix product=yes product_title=Gaetano Donizetti: Linda di Chamounix product_by=Edita Gruberova (Linda), Don Bernardini (Carlo), Monika Groop (Pierotto), Ettore Kim (Antonio), Stefano Palatchi (Prefetto), Anders Melander (Marchese), Ulrka Precht (Maddalene), Klas Hedlund (Intendente). Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra conducted by Friedrich Haider product_id=Nightingale Classics NC 070561-2 [3CDs] price=$45.49 product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/Drilldown?name_id1=3144&name_role1=1&comp_id=32792&genre=33&bcorder=195&label_id=1299Große Opernchöre — Great Opera Choirs

The selection offered here is as diverse as the function of the chorus in the works represented, and this points to the demanding role the chorus has in this genre.

Audiences may be familiar with the version of Borodin’s “Polevtsian Dances” from Prince Igor in its orchestral form, but the music properly belongs to the chorus, who commands the stage for the quarter hour of this scene. As an opening number in this compilation, it is impressive for the stylistic demands placed on the ensemble, and the skill of the Stuttgart group offers a convincing reading of this work. Full of the exoticism found in modal passages, spare and unusual scorings, percussive interludes, and other sound effects. To these sounds the choral forces contribute their own particular colors as Borodin juxtaposed men’s and women’s voices, contrasted smaller ensembles with larger ones, and otherwise manipulated the chorus just as he deftly scored the orchestra.

Some of the choruses are well known enough to have taken on a life of their own, as is the case with the “Triumphal March” from Verdi’s Aida, and its performance here conveys majesty without ostentation. Schrottner offers a crisp reading and avoids indulging the cliches that can mar the piece. As with the excerpt from Prince Igor, Verdi scored the chorus with a variety of colors to suggest the various groups enslaved by the Egyptian pharaoh, and the vocal timbres that the Staatsopernchor brings to the piece are varied sufficiently to create such a sonic tableau.

Other choruses can be more atmospheric, as with the one from Pagliacci, “Andiam, andiam,” which often blends into the staging of Leoncavallo’s opera. Performed apart from Pagliacci, this chorus is effective by itself, and resembles in some ways the famous chorus from Mascagni’s Cavalleria Rusticana with its nuanced choral scene-painting. It is an excellent choice for a concert of opera choruses because of the rare occasions when this excerpt from Pagliacci is heard on its own. Likewise, it is a pleasure to encounter the chorus “Wo ist Moses?” from Schoenberg’s Moses und Aron on this recording. A satisfying excerpt on its own merits, its presence here calls attention to the role the chorus has in that opera. Similarly, the chorus of nymphs and shepherds from Monteverdi’s Orfeo is a fine choice, which represents some of the earliest efforts to include the chorus in the genre. Balancing some of the more familiar choral excerpts, these latter two are worth hearing separately, so that audiences can appreciate their character and which, in turn, adds to the depth of the operas to which each belongs.

Such ensembles can function as characters in their own rite, as with the chorus of exiles from Verdi’s Macbeth or the Russian people in Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov. With the latter, the Stuttgart chorus is highly effective in creating the dramatic tension required in the prologue. The famous “Coronation Scene” requires a strong chorus to set the scene, and this performance offers a fine reading of Mussorgsky’s score. Its dark colors reflect the Russian populace well, just as the lower female voices needed in the first-act “Witches’ Chorus” from Verdi’s Macbeth is appropriately dark in its execution. A well-known excerpt, it is a fine example that uses exclusively women’s voices.

The performance is exemplary, and the recording suggests studio quality, with audience and stages sounds virtually imperceptible. Yet after the last track, the enthusiastic applause shows that this was recorded live and benefitted from the dynamism that arises when an audience is present. The chorus involved certainly would know how to react to the situation, and they carry themselves with elan and intensity. As much as recordings of opera choruses can sometimes, blur, this particular recording contains some fine choices that are not often encountered.

James L. Zychowicz

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Great_Opera_Choirs.png image_description=Große Opernchöre — Great Opera Choirs product=yes product_title=Große Opernchöre — Great Opera Choirs product_by=Staatsopernchor Stuttgart, Staatsorchester Stuttgart, Peter Schrottner, conductor product_id=Profil PH 04046 [CD] price=$15.99 product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/album.jsp?album_id=145215MAHLER: Symphony no. 6

A two-CD set with the first three movements on one disc and the Finale on the second, the release includes the world premiere recording of Hans Werner Henze’s Sebastian im Traum: Eine Salzburger Nachtmusik nach einer Dichtung von Georg Trakl (based on performances given on 22 and 23 December 2005). Despite the overt reliance on three of Trakls’ poems and the inclusion of the texts with the recording, it is a creative pairing with Mahler’s Sixth Symphony.

The latter work, Henze’s Sebastian im Traum is a three-movement symphonic work that lasts about fifteen minutes. While the material by Henze included in the liner notes does not quote the composer as making any direct connection with Mahler’s music or, specifically, his Sixth Symphony, it is difficult not to view Henze’s piece as influenced by Mahler’s symphonic style. Sebastian im Traum is an instrumental work stands between the explicit program implied in the texts and the abstract idiom denoted by the tempo markings in the movement titles, and in this sense it resembles the symphonies from which Mahler had withdrawn his programs and that are still discussed in terms of those connotative texts. Existing between those worlds of meaning, Henze’s work benefits from the references found in Trakl’s verse. The three poems suggest a coming to maturity, and awakening suggested by the setting in Spring at the celebration of Easter, and Henze reflects that perspective in the structure of his music. The style of the piece reflects the dissonant idiom Henze used in his other music, but the clearly defined thematic units and control of tension make the piece accessible. The allusion to Salzburg's night music in the subtitle adds a further connotation that brings up association with the lighter orchestral music of Mozart. Notwithstanding those references, the music merits attention on its own merits. In fact, the middle movement, a Scherzo-like piece, is perhaps the most intriguing for the various ideas Henze expresses in it, and its position at the heart of Sebastian suggests its place in the structure of this work. A fine example of new music, it is a work that merits repeated hearings.