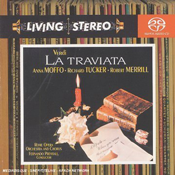

Moreover, the conductor is

a good ‘routinier’ and that’s all that can be said. Nowadays one

doesn’t accept anymore the truncated versions of yore with almost half an

hour of music missing. Still as a memento of three important and fine

American singers or as an alternative to more famous recordings this is a set

not to be despised lightly. Anna Moffo may not be plumbing the tragic depths

of Callas but the voice is sweet and fresh and shimmering with youth. The

coloratura is fine too just before the turning of the B.S Age ( = Before

Sutherland) and the top is strong though the high E at the end of “Sempre

libera” is clearly the end of the voice’s extension. The scooping which

would mar many of Moffo’s later recordings is still absent. One easily

believes (if one shouldn’t know the real facts) that here is a young

soprano probably not more than a few years older than Violetta and thus

utterly credible. Mr. Tucker’s sound may be not to everyone’s taste but

he has a strong personal timbre and good top notes (indeed, Previtali allows

him to drown the other singers in the ensemble at the end of act 2). His

Alfredo however relies too much on sheer vocal force. He is not unstylish but

piano and pianissimo are not in his dictionary. Those sounds he clearly

reserved for his many fine recordings of popular love songs (so did Lanza)

which probably tapped something deeper in his musical mind. As always Robert

Merrill is a tower of strength; delivering every line with unfailing beauty

and roundness of sound. And alas, also as always, not a single phrase remains

stuck in one’s memory. One would offer a lot of money nowadays to hear such

a baritone in the house but a bit boring he remains.

Franco Bonisolli: Recital.

Arias from Puccini, Giordano, Händel, Leoncavallo, Cilea, Ponchielli,

Verdi, Donizetti, Massenet, Lehar, Sieczynski.

Myto 1 MCD 066.339

A worthy souvenir of the tenor, warts included. Myto doesn’t give us a

date or a place when the recital was recorded. Judging from the sound of the

voice I’d say between 1983 and 1988. And I don’t think Bonisolli would

have sung “Wien, Wien, nur du allein (Vienna, Vienna, you alone)” in

let’s say Rome or Madrid. Anyway this is vintage Bonisolli; a singer who

succeeds in leading the listener into ecstasy or rage due to his vocal

strengths or his unmusical sounds. Preferably, all in the same aria. Take

“E la solita storia”. Bonisolli’s voice exemplary caresses and suits

the dreamlike story until it’s time in the second strophe for sobbing,

guffawing and interpolating an ugly high B (listen how Björling succeeds the

same B without sounding vulgar). The tenor once more charms the listener in

“Cielo e mar” until his intonation becomes suspect and he glides in and

out of the right key. “Un di all’azurri” is at least sung homogenously;

which means everything chopped up, shouted and suiting the tenor’s own idea

of rhythm and tempi. And then he surprises us with a fine “Ombra mai fu”;

brilliantly encores with “Wien” and gives us a magnificent high D in Land

of Smiles. And which other tenor was ever so crazy to end a long evening with

“Di quella pira” ? The end result therefore is a mixed bag though one has

to admit this was a real voice. Nevertheless I‘ve a gut feeling that in the

end Bonisolli knew his timbre was not the most sensuous and realized his top

notes didn’t have the cutting edge of that other Franco. Therefore

Bonisolli used some extra musical means to draw attention.

Richard Wagner: Tannhäuser.

Hans Beirer (Tannhäuser), Sena Jurinac (Elisabeth), Martti Talvela

(Landgraf), Janis Martin (Venus), Victor Braun (Wolfram), Jeff Morris

(Walther). Orchestra and Chorus of La Scala conducted by Wolfgang Sawallisch.

Recorded live 1967.

Myto 3 CD’s 3MCD 062.325

When the Bundesrepublik came back into the fold of peoples and the

Deutsche Mark started soaring due to the Wirtschaftswunder (economic miracle)

the great prima donna’s started to perform in Germany again. We owe two

important live performances by Renata Tebaldi to this phenomenon. As they

were broadcasted all over Western Europe I watched both of them almost 50

years ago. I was so disillusioned when I discovered Tebaldi’s Otello was

not Del Monaco but the unknown tenor Hans Beirer. The gentleman had already

many years of strenuous roles behind the belt but no recording firm had ever

thought of offering him a single record. He was almost completely unknown to

people outside the profession. Not without reason as his voice was second

rate and his sense of Italian style owed more to bawling Siegmund than to

singing Riccardo. Soon afterwards I became a subscriber to Opera Magazine

where his name regularly popped up. I couldn’t understand why he was

allowed to sing in a temple as La Scala. Nowadays when we see things in a

more historical perspective reasons for his Scala performances are more easy

to explain. Like all other major European theatres La Scala was slowly

dumping old traditions; one of them singing opera in a language the audience

could understand. This Tannhäuser was one of the first productions to be

sung in the original German (as late as 1974 Jenufa was still performed in

Italian).Another reason for the German version was the fact that no major

Italian tenor could be found to sing the role of Tannhäuser. Gone were the

Wagner-days of Gino Penno, Mario Del Monaco (Lohengrin at La Scala) or

Giuseppe Di Stefano (Rienzi in the same theatre). So Beirer came in and at

first the sound is not a thing of beauty; dry, unattractive timbre,

resemblance with 70year old Rudolf Schock. But at the end of Act 1 the voice

becomes more powerful while he never roars. During the rest of the

performance he has found his Vickers-sound; beefy but with some shine on it.

In short a real pro who absolutely knows how to pace. The same is noticeable

in the long bonus scene from Siegfried recorded at San Carlo two years later

(he was 58). There is not much lustre in his dialogue with Mime but when the

forging song is there, so is the voice. As could be expected Sena Jurinac is

a splendid Elisabeth. With her warm Slavonic sound (half-Italian, half

German; combining the best of two worlds) she succeeds in making Elisabeth

less virgin and more woman. Only at the top of the voice is the sound a bit

frayed as she too was already a veteran of many operatic wars. Janis Martin

is not especially erotic and in her clear light sound one already hears a

soprano struggling to come out. In fact, on record Jurinac sounds more

sensuous than Venus. Martti Talvela is an imposing Landgraf and Victor Braun

delivers an excellent ode to the evening star. He too didn’t have much of a

recording career and his big voice easily fills La Scala; at the same time

showing warmth and charm. Sawallisch is sympathetic to his singers, never

rushing them in what is after all a voice-wrecker for the tenor. It comes as

a surprise though that the La Scala chorus sounds rather tame, less incisive

and powerful than usual. Then one remembers that this generation was asked to

sing for the first time in a completely foreign idiom.

Giuseppe Verdi: Rigoletto.

Margherita Rinaldi (Gilda), Luciano Pavarotti (Duca), Piero Cappuccilli

(Rigoletto), Nicola Zaccaria (Sparafucile), Adriana Lazzarini (Maddalena),

Plinio Clabassi (Monterone). Orchestra and Chorus of the RAI-Torino conducted

by Mario Rossi. Recorded live 1967.

Myto 2CD’s 2MCD 064.330

This RAI-performance reminds me of a 1969 performance at De Munt in

Brussels with almost the same cast. Cappuccilli and Rinaldi sang their

Rigoletto and Gilda while Luciano was the duke (Luciano Saldari however was

not a Pavarotti). The singers on this radio-performance are as excellent as

they were in the theatre; filling the recording with well-focused sound and

convincing vocal acting. Still a good evening in the theatre can sometimes

fall a little bit flat when one relives the experience without the visual and

aural surroundings and this is a prime example. Piero Cappuccilli is his

well-known self; letting forth a stream of perfect sound in that brown colour

only the real Italian(ate) baritone possesses. From top to bottom the sound

is rock firm and he has a splendid G at his disposal as proven by the end of

“Si vendetta”. I’ve seen and heard him countless times and he was

always excellent and yet I think he was the Italian answer to Robert Merrill:

a wonderful voice which rarely moved you (unless he sang his magnificent

Boccanegra) or made you go back to his recordings. Margherita Rinaldi

doesn’t put a foot wrong. She had a clear ‘virginal’ voice easily

sailing to a D without the sharper edge of lesser Italian sopranos in this

repertoire. Of course Myto gambles on Luciano Pavarotti’s appearance in the

cast. He studied the role with Tullio Serafin, a real singer’s conductor

who nevertheless according to Philip Gossett’s book on performance

tradition, didn’t have much feeling or interest in historical belcanto.

Pavarotti is splendid. He had been singing for six years and the overtones of

a young and fresh voice are still there while the vocal technique is now very

secure (the one chink in his vocal armour is his lack of a true piano). But

Maestro Rossi is a Verdi-conductor in the Serafin-tradition: well-chosen

tempi but no interest in the original score and preferring the provincial

traditions. By 1967 all recorded Rigoletto’s already had the Duke’s

cabaletta which is completely cut here. And singers already knew that

“Parmi veder le lagrime” and the duet “ E il sol” had important

cadenzas. None of it can be heard here though the tenor recorded them

officially only a few years later. The rest of the cast is interesting.

Plinio Clabassi (the former Mr. Rina Gigli) can still curse impressively as

Monterone but his colleague Nicola Zaccaria is dull as Sparafucile. And that

not everything Italian was gold is proven by Adriana Lazzarini. Several times

I experienced her performances myself while visiting Italy and the hollow

sound on this recording is exact as I remember her.

Vincenzo Bellini: I Puritani.

Virginia Zeani (Elvira), Mario Filippeschi (Arturo), Andrea Mongelli

(Giorgio), Aldo Protti (Riccardo), Vito Susca (Gualtiero). Orchestra and

Chorus of The Teatro Verdi Trieste conducted by Francesco Molinari Pradelli.

Recorded live 1957.

Bongiovanni 2 CD’s GB1195/96

As alternatives to official recordings go, this is one that can be

recommended. The radio sound was not state of the art, even at the time, but

it is the orchestra that suffers most. And the singers, all used to a healthy

dose of Verdi and Puccini, will probably not earn kudos by Philip Gossett for

their immaculate belcanto style. But voice and voice and voice again we get

in generous doses. Best of all is Virginia Zeani of course. Together with

Olivero and Gencer she may thank pirates for helping her name into the

pantheon of sopranos. The fifties were her great years and what a shame she

didn’t get more official recordings. From the first measure on one listens

spellbound to the magnificent Rumanian. She may not be the great vocal

actress Callas was but neither has she the sour sounds the American soprano

made, even in her good days. Zeani’s voice is personal, throbbing with

emotion and utterly fearless in the high register. Whenever possible and

preferably at the end of an ensemble she takes the higher option and sends

the audience into a delirium. As a coloratura she is no Sutherland as she was

not raised in classical belcanto with its ornamentations but her involvement

is so much greater than the Australian and she knows how to float her voice

without becoming sugary. Indeed, it seems to me that Zeani combines the best

of Sutherland and Callas. Enter Mario Filippeschi; known from his Pollione

with Callas when not in his best voice (his recitals on Bongiovanni culled

from live performances are far better). The voice is a bit unyielding,

lacking suppleness for Bellini and has a slightly whining quality. One should

not expect subtleties or even a great singing technique. There is no messa di

voce as on the legendary “A te o cara”recordings by Alessandro Bonci and

Giacomo Lauri-Volpi. But if you like your tenors to have metal, even pure

steel, and squillo and stamina in the voice this is the man to go for. The

top notes are splendid and he is breathtakingly efficient when during

“Vieni” he sails together with Zeani to a stunning high D (he was 50).

Another veteran is Bass-baritone Andrea Mongelli. He too was a popular house

singer throughout Italy though almost unknown elsewhere. He saved the

recording of the early EMI-Fanciulla when he stepped in at the last moment

for Tito Gobbi. His Riccardo is authorative and warm and the voice sounds

homogenous from low to high in this bass-baritone role. Aldo Protti too,

another big voice, is not the first baritone one thinks of in this

repertoire. He is used to big outbursts of sound and though his emission is

very easy one feels his phrasing is a little bit stiff. But he has reserves

of power and typically for the time a fearless top. He easily takes the high

G in his cabaletta (one verse only) and one hears he still has a few notes in

reserve. Therefore when Mongelli and Protti meet in their big duets, all

stops go out and the house almost becomes hysterical. One doesn’t associate

Francesco Molinari Pradelli with Bellini and his is not the most subtle

reading. He is nearer to Un Ballo or Trovatore than to Bellini but how could

he otherwise with such powerhouses of voices in front of him ? This Puritani

is a worthy testimony to a gone tradition, though not for Bellini puritans.

It may not be fare for every day. But I’m sure we would screech our heads

off if we would get a performance like this one now and then.

Gaetano Donizetti: Lucia di Lammermoor

Renata Scotto (Lucia), Carlo Bergonzi (Edgardo), Mario Zanasi (Enrico),

Plinio Clabassi (Raimondo), Mirella Fiorentini (Alisa). Orchestra and Chorus

of NHK conducted by Bruno Bartoletti. Recorded live Tokyo 1967.

Myto 2 MCD 065.337

This recording is an issue only for those who collect every CD with the

names of Scotto or Bergonzi on it. Is this a bad performance ? Far from it

but as NHK broadcasted it on Japanese TV there is a (rather expensive) DVD

available. So one can watch one of the four existing complete live

performances by one of the greatest tenors of the post-war period (the other

three being Aida, Elisir and Ballo while up to now nobody has ever thought of

extracting his 1968 RAI-TV Inno delle Nazione from the vaults). Such a rare

live visual document of tenor and soprano makes one more tolerant of the two

barbarous cuts; the Lucia-Raimondi and the Edgardo-Enrico duets which when

absent on record are unpardonable sins. Bergonzi himself had recorded only a

few years earlier (with Moffo-Sereni) a really complete Lucia but he was

notoriously sticking to Italian provincial habits. He was always rambling

about “our great Verdi” when a producer didn’t stick to utterly

conventional productions but the scores of that same “great Verdi”

didn’t mean much to him when he could cut corners. In 1966 he was almost

threatened with murder during a Dallas Rigoletto and he nevertheless refused

to sing even a single verse of “Possente amor”; a cabaletta he had

recorded for DG. Therefore I’d advise anyone to buy the DVD or the complete

RCAset. Not that this Tokyo-perfrmance is inferior. The tenor sings with his

usual ardour and feeling for the line. Of course in a live performance, the

small sobs are a little bit more pronounced but his final scene, as always

during the sixties, is a ‘tour de force’; an object lesson in belcanto

which every student should student for beauty of tone and exemplary

breathing. The bonus gives us some highlights from his first Werther in

Naples in 1969, sung in Italian. Bergonzi, an autodidact and one to leave

school too early, never learned another language than Italian and thus we are

deprived of some possible great performances of French opera. Nevertheless

Werther was one of the few roles (together with a Don José who is still

missing) he studied in the original language 4 years later. It is a pity Myto

didn’t use that far more rare interpretation than the Naples one which has

already appeared on other labels.

Yes, I know the opera is called Lucia but Renata Scotto was never in the

same league as the tenor. She officially recorded the role in 1959 for the

short lived label of Ricordi (with Di Stefano-Bastianini). This is one of the

five or six live-recordings available, almost all of them better than the

early official recording. The voice grew and got more tragic undertones; the

phrasing became more interesting (owing a lot to Callas). Still she never

succeeded in overcoming completely one natural handicap. There is something

acid in her voice; a sharp edge which makes some listeners uncomfortable. It

is the sound non-operatic people always imitate to ridicule an operatic

soprano. Granted, as I witnessed myself often during her prime, it was less

obtrusive in the flesh but absent it never was. It is not very noticeable

here in “Regnava nel silenzio” but as the performance continues it slowly

makes its appearance. Her coloratura in the madness scene is fine though one

nevertheless has more an impression of hard work than of natural talent. She

remains a lirico with coloratura facility lacking however the easy top. The C

in “Il dolce suoneo” is short and slightly flat and so is the E in

“Spargi d’amore pianto” which ends in a small cry.

Baritone Mario Zanasi clearly thinks of Enrico as a kind of Amonasro. The

voice is excellent but the style is more than rough and ready. Singing to the

baritone means clearly to cling as long as possible to any high note on his

road. This is a one dimensional portrait of a villain in which there is no

place for mellowness, pity for the fate of his sister and remorse during the

madness scene. I suppose Plinio Clabassi still had it in him to be a good

Raimondi but as his big scene is cut there is not much to comment on. Angela

Marchiandi however is one of the most wretched Arturos to be found on record.

The singers conduct well and Bruno Bartoletti follows them nice and dry.

Mitigating circumstances are that he has to work with an orchestra not well

versed in this repertoire while his Japanese chorus is underpowered.

Jan Neckers