January 29, 2008

Peter Grimes: Grim, gripping and glorious

[Daily Telegraph, 29 January 2008]

[Daily Telegraph, 29 January 2008]

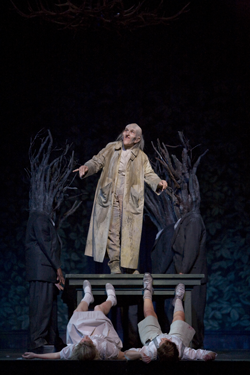

Rupert Christiansen reviews Peter Grimes performed by Opera North at the Grand Theatre, Leeds

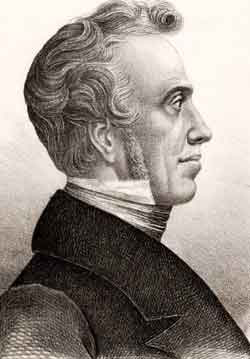

Serge Koussevitzky, the philanthropic conductor who commissioned Peter Grimes, claimed that the result of his munificence was "the greatest opera since Carmen". Well, perhaps he was biased, but a performance as enthralling as this makes his flush of proud enthusiasm understandable.

January 28, 2008

Two Queens in Full Cry

Mariella Devia may not be the flavor-of-the-month in “au courant” operatic circles; she may not be giving come-hither looks in the current round of air-brushed Rolex ads; nor may recording companies be promoting her in hyper-drive as the next “diva du jour” (read: meal ticket).

Nevertheless, in La Scala’s new and highly effective “Maria Stuarda,” Signora Devia scored her considerable artistic triumph the old-fashioned way, free of hype and extra-musical baggage, by simply showing up and singing the living hell out of the titular queen, like any truly great star surely should.

I first heard this wonderful artist. . .well, a number of years ago, and I remembered hers to be a full, flexible, accomplished lyric voice with good thrust. Not a fussy, artsy interpreter, she made fine effect with heartfelt, well-studied vocalizing, sound technique, and simplicity of gesture. The good news is that, lo, these many years later, although time has darkened the instrument a bit, this accomplished soprano is still singing superlatively well. And she still looks petite and lovely, to boot.

Ms. Devia has all the requisite assets at her command to make a most persuasive case for our heroine. She negotiates even the trickiest coloratura with skill and accuracy, and imbues it with dramatic meaning. She scores every single time with spot-on, thrilling notes “in alt.” Indeed at opera’s end, she sang what seemed like a “q” above high “z” sounding as fresh as at the start, beginning the note at moderate volume and swelling to a full-bodied forte. Throughout, she displayed masterful use of portamento, crafting arching lines which were often achingly beautiful. And she called forth some steel in her tone and starch in her demeanor as needed to drive the drama forward in her important confrontational declamations.

If this seasoned soprano seems to employ a few small “tricks” these days, like slightly veiling soft high notes that are approached with a leap rather than a scale progression, and pacing her volume here and there to conserve her full arsenal for the “money” sections, it is very minor quibbling. Mariella Devia has all of the goods (and some to spare) to successfully take on this demanding role and make a notable star turn out of it. The Milanese public rewarded her with a deafening appreciation at final curtain.

Mariella Devia, Anna Caterina Antonacci, Francesco Meli, Carlo Cigni (Act I)

Mariella Devia, Anna Caterina Antonacci, Francesco Meli, Carlo Cigni (Act I)

Happily, we were just as lucky with our other queen, in the guise of Anna Caterina Antonacci’s “Elisabetta.” The tall, lanky, and beautiful Ms. Antonacci was every bit her rival’s equal, proving to be a perfect foil physically and musically. For ACA has a rangy, disciplined, highly individual, and powerful voice, with a fair measure of metal -- and a big measure of mettle -- driven by technical mastery. This “seconda donna” also scored big with the vociferously appreciative crowd for her imposing glamorous star presence as much as for an imperious outpouring of focused sound.

The program book referred to a past successful (1971) Scala production of “Maria Stuarda” with the established stars Shirley Verrett and Montserrat Cabelle. It couldn’t help but provoke my comparing “what was” to “what is” and I have to say that Mesdames Devia and Antonacci seemed to more than hold their own up against such a previous fabled pairing. Blessed is the house that can find two complementary divas of such stature, not once, but now twice in its recent history. Bravi.

The scheduled tenor Francesco Meli was indisposed, so “Leicester” was capably assumed by Dario Schmunck. Mr. Schmunck is currently singing such things as “Elvino,” “Alfredo, “ and “Leicester” around European houses, and was already scheduled for it at La Scala later in the run. He is possessed of a perfectly pleasant lyric voice which he uses intelligently.

In a major house as this, I thought he would be, say, a perfect “Cassio,” but “Leicester” is decidedly a much bigger “sing,” calling for leading man star quality and panache that he does not yet quite fully possess.

His first aria was greeted with a derogatory comment (shouted by one of the claquers?), and he certainly did not deserve that. His enjoyable performance does still seem a work in progress, and while unfailingly pleasant and well-sung, Schmunck was not quite on a level of fire power with our two queens, from whom he notably took considerable inspiration in each of the separate duets.

Piero Terranova’s “Cecil” began somewhat tentatively. Indeed in Act One, his important solo rants were curiously weak-voiced and covered by the orchestra. Thankfully, he progressively found his stride, and by Act Three he was offering compelling, full-throated singing. “Cecil” may be a comparatively small role, but he fuels so much of the conflict that it was welcome for Terranova to come to the party in due course.

Carlo Cigni brought beauty and amplitude of tone, fine vocal presence, and sincere acting to “Talbot.” In the minor role of “Anna,” Paola Gardina displayed an uncommonly beautiful voice, one not usually lavished on such a small part. I look forward to encountering both Cigni and Gardina in future performances and larger assignments. The exemplary choral work was prepared by Bruno Casoni.

Musical values were of a very high standard. Maestro Antonio Fogliani led the excellent resident orchestra in a taut, largely unsentimental reading, that still allowed for breadth of utterance as well as touching, highly introspective musings such as in the famous Act III prayer. Especially in the sextet and the larger choral moments, Fogliani commanded admirably clean control of his assembled forces to exciting musical effect.

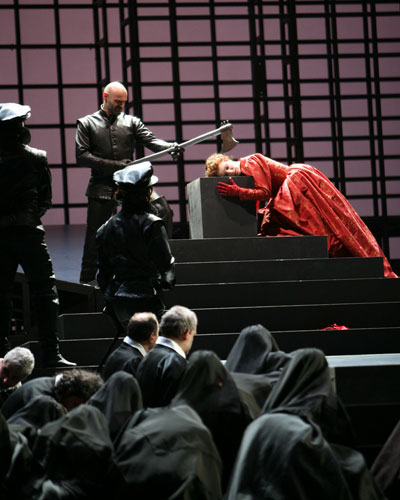

The venerable Pier Luigi Pizzi did his usual triple duty as set designer, costume designer, and director. The costumes were sumptuous, character-specific, evocative if not slavishly “period-correct,” and meaningful. His Elizabeth-as-Fashionista “take” worked well, and Antonacci seemed to revel in her spiffy duds. Mary’s silvery-black frock may have had the required austerity but it was elegantly handsome; and topping all else in the show, her spectacular red dress for the final prayer and execution (forgive me) was to die for.

The handsome, functional set was framed within a sort of “box” of industrial scaffolding that suggested a prison. Centered within it were gradated stepped platforms, shaped rather like an Incan pyramid, the top level of which was joined to perimeter walkways by three symmetrical ramps. By using different lighting washes on the cyclorama, many evocative silhouettes could be created. However, Mr. Pizzi’s floor plan did tend to restrict traffic patterns to a certain sameness of movement for the larger scenes.

Pizzi created a truly brilliant effect for the garden, in which we first encounter Queen Mary. The “pyramid” having been surreptitiously retracted, a full grove of life-like trees rises from underneath the stage like a veritable “dawn” of greenery, including an astro-turfed “bank” on which Mary can luxuriate and stroll. Other than this beautifully calculated forest, the overall unit setting was not intended to communicate a literal sense of time or place, but it was very pleasing to look at and functional.

Anna Caterina Antonacci (Elisabetta)

Anna Caterina Antonacci (Elisabetta)

The prison metaphor not only worked for the obvious enclosure of Mary, but suggested that “Elisabetta” was perhaps in her own “prison,” being constrained by the royal behavior and sometimes unpleasant duties expected of rulers. Part of the design concept was creating a sort of “living sculpture,” peopling this setting with omnipresent guards who prowled the structure brandishing torches. This leather clad, eye candy ensemble of strapping young men may not have added all that much, but neither did it unduly distract.

The high accomplishments of Pizzi the designer were not quite matched by Pizzi the director. I am grateful indeed that there was no bizarre “concept” imposed, that the groupings and stage placement were always serviceable and the movement cleanly competent, all of which told the story and allowed the artists to sing their best. And, yes, that famously bitchy duet scene between the two queens certainly made its full mark, and there were some lovely personalized touches overall.

Still, I had the feeling that there was more to be mined dramatically out of two such wonderful sopranos, especially the always creative Ms. Antonacci, whose “Elisabetta” seemed to settle for two-dimensions when my experience with her in past performances has shown she is fully capable of three (or more).

The one concession to modest “innovation” was that during the opening bars of the first scene, a pantomime was created in which our heroine is given communion by “Talbot,” effectively establishing her faith-based credentials and defining her predicament. (Although, since she later unceremoniously and rousingly calls her cousin a “vile bastard,” I was thinking: “And you take communion with that mouth, Miss Mary?”)

It has been said that acting is really listening. . .and re-acting. And here I think lay a (fixable) minor shortcoming of the production. Characters aren’t consistently listening to each other. And reacting. The above mentioned epithet may be the most glaring (but not only) example, for after “Maria” hurled “Vil bastarda!” at “Elisabetta,” there was scant-to-no-reaction, with “Anna” actually just remaining complacently seated. I mean, the take-no-prisoners Queen has just been insulted (all right, all right, she has taken one or there would be no story)! I would hope that some minor tweaking and enhanced character interplay could be instilled that could make an already fine evening even finer.

In past years, much ink has been spilled and hands wrung about the state of the art at La Scala. At least based on this visit, its reputation as one of the world’s leading opera houses has emphatically been sustained. A tour of their adjacent museum was revelatory as to how this lofty regard came to be established in the first place, since it contains numerous terrific portraits, photos, mementos, props, scores, letters, and instruments touched by many (perhaps most) of the greatest composers and interpreters of the last 200 years of operatic history, all of whom gifted their musical talents to La Scala.

Scene from Act II

Scene from Act II

It is also telling that, currently on view, there is a special display of costumes worn by Maria Callas for all the roles she performed at the house. This remembrance of the thirtieth anniversary of her death offered a reminder, should any be needed, that we would not perhaps be hearing “Maria Stuarda” and a good deal of the bel canto repertoire in wide performance today were it not for La Divina’s blinding talent and trail-blazing musical advocacy.

Maria may be gone but it seems La Scala can still summon up greatness, as Mariella Devia and company aptly demonstrated. The Queen is dead. Long live the Queen.

James Sohre

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Maria_Stuarda_Devia.png image_description=Mariella Devia as Maria Stuarda (Photo by Marco Brescia courtesy of Teatro alla Scala) product=yes product_title=Gaetano Donizetti: Maria Stuarda product_by=Above: Mariella Devia (Maria Stuarda)All photos by Marco Brescia courtesy of Teatro alla Scala

January 27, 2008

'Judas Maccabaeus'

L.A. Opera performs the work at the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels.

L.A. Opera performs the work at the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels.

By Chris Pasles [LA Times, 28 January 2008]

Many go to war, but few return. That was the striking image in the Los Angeles Opera production of Handel's "Judas Maccabaeus" on a rainy Saturday night at the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels.

Italian girl charms with humour, style

(Photo by Devon Cass)

(Photo by Devon Cass)

Lloyd Dykk [Vancouver Sun, 27 January 2008]

VANCOUVER - The lovable opera L'Italiana in Algeri, The Italian Girl in Algiers, gives us a good picture of what Gioacchino Rossini must have been like: a witty rascal, a bon vivant, as brilliant a concocter of music as he was of food.

Soprano shines in silly `Pearl Fishers' As the spurned Zurga violently.

BY LAWRENCE A. JOHNSON [Miami Herald, 27 January 2008]

BY LAWRENCE A. JOHNSON [Miami Herald, 27 January 2008]

As the spurned Zurga violently assaults Leila, who has rejected him for his best friend Nadir, a gentleman in the audience turned to his wife and said, ``They didn't do this in Boston.''

„Eugen Onegin“: Pique Dame als Psychothriller

WILHELM SINKOVICZ [Die Presse, 25 January 2008]

WILHELM SINKOVICZ [Die Presse, 25 January 2008]

Oper. Aufregend, filmreif: Kirill Petrenko und Regisseur Peter Stein zeigen in Lyon den wahren Tschaikowsky.

Die Neuproduktion von „Eugen Onegin“ im Vorjahr war eine der schönsten, geschlossensten Opernaufführungen, die sich denken lassen. Nun haben der Dirigent Kirill Petrenko und Regisseur Peter Stein ihren Puschkin-Zyklus in Lyon mit „Pique Dame“ fortgesetzt und abgeschlossen, eine aufregende Aufführung, spannend wie ein Psychothriller und nur aufgrund zweier Umbesetzungen in letzter Minute nicht ganz auf jener atemberaubenden künstlerischen Höhe angesiedelt wie die märchenhafte Vorgängerproduktion.

The Master Class Continues

BY FRED KIRSHNIT [NY Sun 25 January 2008]

BY FRED KIRSHNIT [NY Sun 25 January 2008]

Marilyn Horne's annual song series, known as The Song Continues, offers a cornucopia of events for the music lover but, with the press of time being relentless, one has to make choices. I opted for a Wednesday recital at Weill Hall because it included, among a program of rarities, a chance to experience a world premiere.

TRAETTA: Ippolito ed Aricia

Music composed by Tommaso Traetta. Libretto by Carlo Innocenzo Frugoni after Simon-Joseph Pellegrin’s Hippolyte et Aricie.

First Performance: 9 May 1759, Teatro Ducale, Parma

| Principal Characters: | |

| Theseus [Teseo], king of Athens | Tenor |

| Hippolytus [Ippolito], son of Theseus | Soprano/Castrato |

| Phaedra [Fedra], Theseus' wife, stepmother to Hippolytus | Soprano |

| Oenone [Enone], nurse and confidante of Phaedra | Soprano |

| Aricia, princess of the blood royal of Athens | Soprano |

| Diana, a goddess | Soprano |

Synopsis of Phèdre by Jean Racine based on Hippolytus by Euripides and Phaedra by Seneca:

Act I

Theseus, king of Athens, has disappeared during one of his expeditions. Hippolytus tells Theramenes of his intention to search for his father. But this is not the real reason he wishes to leave Troezen, where the court has been in residence for some time. Neither does he desire to avoid the persecution of his stepmother, Phaedra. His only motive is to escape the charms of Aricia, the only survivor of the royal family who formerly ruled Athens. He is in love with her, and his father has forbidden her to marry.

Oenone, Phaedra's nurse, announces her mistress, but Hippolytus wishes to avoid an unpleasant meeting, and departs. The queen's behavior, and her conversation with Oenone, betray her incestuous and forbidden love for Hippolytus. She wishes for death, but the sudden announcement of Theseus' death puts a new complexion on things. Free to indulge her passion, she gives up her suicide plan in order to arrange an alliance with Hippolytus against Aricia, to preserve her own son's right to the throne of Athens.

Phèdre et Hippolyte by Baron Pierre-Narcisse Guérin (1802)

Phèdre et Hippolyte by Baron Pierre-Narcisse Guérin (1802)

Act II

Ismene, Aricia's confidante, announces Theseus' death to the young girl and in the same breath reveals her suspicion of Hippolytus' romantic feelings for Aricia. Incredulously the young girl listens to a revelation that enchants her, since she, in turn, has fallen in love with Hippolytus. Hippolytus soon confirms the confidante's speculation in a tender but awkward confession. The interview is interrupted by the announcement of Phaedra's arrival, but not before Aricia has timidly admitted her own feelings.

Phaedra comes in with the purported intention of pleading for her son. However, carried away by her passion, she forgets her original purpose and reveals her secret love. Crushed by Hippolytus' horrified reception of her declaration, she takes his sword to kill herself. As she rushes out, Theramenes comes in with a momentous rumor: Theseus may be alive. Hippolytus decides to investigate the rumor and to fight against Phaedra's claim to the throne and in defense of Aricia's rights.

Act III

Phaedra's confession has had an unexpected result. In spite of her humiliation, her hopes have been revived and she now urges a reluctant Oenone to plead her case with Hippolytus. However the situation changes drastically with the news of Theseus' return. At first Phaedra, panic-stricken, again threatens suicide, then yields to Oenone's perfidious plan to accuse Hippolytus of attempting to seduce her. When Theseus comes in, Phaedra departs with a cryptic hint. Hippolytus also leaves with a lame excuse.

Act IV

At the beginning of the scene, Oenone completes the slanderous accusation against Hippolytus introduced offstage. The credulous Theseus is completely deceived. When Hippolytus appears, Theseus wonders indignantly at his son's innocent appearance and greets him with immoderate accusations, culminating in a prayer to Neptune for revenge. Hippolytus, out of filial consideration, defends himself by pointing out his reputation for virtue and reminding Theseus of Phaedra's ancestry, and by confessing his love for Aricia. Theseus rejects the last argument as a mere ploy.

Detail from Phèdre et Hippolyte by Baron Pierre-Narcisse Guérin (1802)

Detail from Phèdre et Hippolyte by Baron Pierre-Narcisse Guérin (1802)

Meanwhile, Phaedra, stricken by remorse, goes to see Theseus to plead for Hippolytus. But she changes her mind when Theseus unwittingly reveals to her that she has a successful rival. She becomes hysterical with jealously and rage. Finally, however, she repents and repudiates Oenone, the instigator and agent of her treachery.

Act V

Still refusing to clear his name, Hippolytus decides to flee but before leaving, arranges a rendezvous with Aricia so that they may wed. Immediately after his departure Theseus abruptly appears. In spite of her embarrassment, Aricia stands up to him and defends Hippolytus' innocence with such conviction that the king's certainty is shaken. He calls for Oenone and is even more deeply disturbed when a servant reveals Oenone's suicide and Phaedra's irrational behavior. Theseus, at last, is willing to reconsider his belief in his son's guilt, but it is too late. Theramenes comes in with the harrowing tale of Hippolytus' death. Phaedra arrives and clears Hippolytus, then dies of the effects of a poison she has taken earlier. Grief-stricken, Theseus vows to make full amends to his son's memory and to treat Aricia as his daughter. [Diana restores Hippolytus to life and reunites the couple.]*

[Synopsis Source: CliffsNotes]

Click here for the livret of Hippolyte & Aricie.

* Added by Pellegrin

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Phedre_et_Hippolyte_Guerin_.png image_description=Detail from Phèdre et Hippolyte by Baron Pierre-Narcisse Guérin (1802) audio=yes first_audio_name=Tommaso Traetta: Ippolito ed AriciaWinAMP, VLC, FooBar first_audio_link=http://www.operatoday.com/Ippolito.m3u product=yes product_title=Tommaso Traetta: Ippolito ed Aricia product_by=Ippolito: Madeline Bender

Aricia: Patrizia Cioffi

Fedra: Laura Claycomb

Teseo: John McVeigh

Enone: Gaële Le Roi

Diana: Anne-Lise Sollied

Les Talens Lyriques, Christophe Rousset (cond.)

Live performance, 23 February 2001, Montpellier

January 25, 2008

New Lyric season plays it safe

2008-09 schedule avoids risk, stays in mainstream

2008-09 schedule avoids risk, stays in mainstream

By John von Rhein [Chicago Tribune, 24 January 2008]

Change, that overworked buzz word of the political season, does not seem to have seeped very far into the artistic mindset of Lyric Opera of Chicago.

January 24, 2008

Wagner: Orchestral Hightlights from the Operas

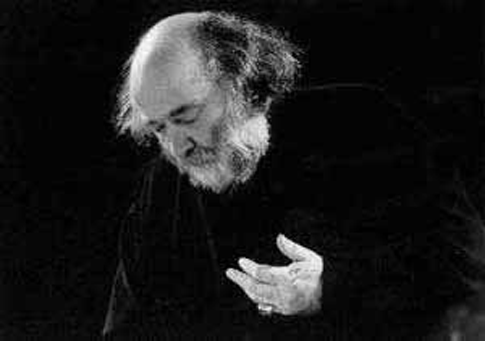

With the veritable lexicons of motives that occur in his overtures and preludes, as well as thematic summaries in various interludes, the famous orchestral excerpts performed in concert communicate some aspects of the operas well. Yet under the baton of a solid Wagnerian likethe late Klaus Tennstedt, the music takes on added dimensions that convey the passionate expression found in the scores. This is already evident in the legacy of recordings that Tennstedt left, and this recently released DVD of a concert of the London Philharmonic on tour at Suntory Hall, Tokyo, on 18 October 1988, captures some of the dynamic aspects of the conductor on the podium.

While Tennstedt’s involvement with Wagner’s music is evident in the recordings that are already available, a concert video like this helps to document the artist interacting with his orchestra. Through a combination of shots that varying in size, this film shows the orchestra as a whole, various sections, and also close-ups of the conductor himself, in works Tennstedt was regarded highly as one of the finest interpreters of his time. As familiar as this music can be, a master like Tennstedt contributes nuance to the well-known overture to Wagner’s opera Tannhaüser with the subtle variations in tempo. At times the intensity emanates from the podium, with Tennstedt’s baton almost vibrating in his hands. Elsewhere, it is the facial expression that brings about the appropriate response, as in the evocative Bacchanale that follows the Overture in this concert. The fine sonics of this recording demonstrate the unified playing that Tennstedt did not demand, but drew out of the exceptional players of the London Philharmonic.

With an earlier work like Rienzi, the elements of grand opera emerge clearly in Tennstedt’s interpretation. Here the broad strokes are necessary, as the longer themes that Wagner used in this relatively early opera are stylistically removed from the idiom he would use in Tannhaüser or, later in Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. With some of the longer note values and sustained pitches that are characteristic of Rienzi Tennstedt creates some tension that evoke the charged situations in the opera. Familiar in the concert hall, the overture to Rienzi receives a solid interpretation with Tennstedt, who makes the most of the score without overly emoting.

Yet it is in the excerpts from Wagner’s Ring der Nibelungen that Tennstedt seems to have been in his idiom, and the selections included in this concert represent his music-making very well. With “Dawn and Siegfried’s Rhine Journey” and “Siegfried’s Funeral Music,” Tennstedt connotes the sense of the scene painting that is a crucial element in the opera Götterdämmerung, from which they are taken. While maintaining decorum, Tennstedt brings out an almost raucous jubilation that stands in contrast to the somber and intense tone of the “Funeral Music” that follows the hero’s murder. Here the London Philharmonic plays passionately while rendering the score with an almost classic precision.

After such intensive music, Tennstedt included two further selections, the overture to the comic opera Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, and the final piece on the concert, the famous “Ride of the Valykyries” from Die Walküre. Well known as it is, the placement of the “Ride” at the end of the program precludes any kind of encore – what could possibly follow that would not be anticlimactic. And it is appropriate for the video to end with the visage of Tennstedt in freeze-frame, an image that remains in memory long after hearing this well-played concert of the London Philharmonic on tour in Japan. The liner notes include Tennstedt’s comment that he is not on the podium just to “beat time,” and the craft that he brought to his work as conductor is evident in this filmed concert.

James L. Zychowicz

Madison, WI

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Wagner_Highlights.png

image_description= Wagner: Orchestral Hightlights from the Operas

product=yes

product_title= Wagner: Orchestral Hightlights from the Operas

product_by=London Philharmonic Orchestra. Klaus Tennstedt, conductor.

product_id= EMI Classics 0946 3 91008 9 7 [DVD]

price=$21.99

product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/Drilldown?name_id1=57081&name_role1=3&label_id=5837&bcorder=36&name_id=12732&name_role=1

Turkmenistan ends ban on opera and circus

[Reuters, 21 January 2008]

[Reuters, 21 January 2008]

ASHGABAT (Reuters) - Turkmenistan will end its seven-year ban on opera and the circus introduced by the Caspian nation's former eccentric leader, state media reported.

Italian opera on Gala

As with most of their sets, for the 1972 Turandot Gala offers the complete performance and then fills the second disc up with extracts from performances by one of the key singers from the title performance.

But Gala doesn’t follow this practice for the Attila, oddly enough, since it preserves a great performance from Samuel Ramey. The bonus cuts here go to well-known artists from the same era as those of the Attila. From performances under Claudio Abbado at La Scala in 1979, we hear Placido Domingo in Luisa Miller, and a trio of Don Carlos arias, featuring Yevgeny Nestrenko, Leo Nucci, and Katia Ricciarelli. Piero Cappucilli closes the CD with an elegant “Eri tu” from Un ballo en Maschera.

However, after hearing this rough but exciting Attila, closing the set with some more Ramey, or at least excerpts from other early or rare Verdi, would have been wonderful. Be that as it may, the opera has the benefit here of a fiery live performance, recorded in clean if not expansive sound. Ramey has the audience on his nasty Hun side from the beginning, and a raucous crowd demands a bis of “Oltre a quel limite t’attendo.” Some may regret the current state of the singer’s voice, but here the enveloping darkness of his bass is firm and yet flexible. Another American sings Odabella — Linda Roark Strummer. She has a wild, apparently huge voice. While not exactly refined, her lunging high notes and aggressive approach suit the character. Veriano Luchetti, as Foresto, brings a reliably vivid Italian tenor sound to the mix. William Stone is a capable if somewhat bland Ezio. The chorus and orchestra know the idiom and perform it with exuberant professionalism, under the baton of Gabriele Ferro.

The 1972 Turandot, recorded at the Teatro Petruzzelli, suffers

from poor sound, with the source apparently being an audience member (if the

occasional chatter is any clue). Often the singers seem to be caught in a

stage position that allows the orchestra to cover their voices. In a few

places the tapes seem to have deteriorated, leading to sudden jumps. At any

rate, the performance, while decent, hardly suggests that the unsatisfactory

sound is any tragedy. Gala gives star billing to Marion Lippert, a German

soprano whose career eventually took her to a couple dozen performances at

the Metropolitan Opera. The booklet essay quotes some reviews that praise her

stage demeanor in the role, which obviously cannot be evaluated in this

recording. Although not uncomfortable with the role’s challenges, she brings

little that is individual. Flaviano Labó ducks a couple of optional high

notes, but he sings a handsome, manly Calaf. Lydia Marimpietri earns the

usual happy applause for Liu’s melodic, sad arias. She is fine, but the

applause really should go to the composer. With the sound in its lamentable

state, making judgments about Napoleone Annovazzi and the theater orchestra

would be unfair.

The 1972 Turandot, recorded at the Teatro Petruzzelli, suffers

from poor sound, with the source apparently being an audience member (if the

occasional chatter is any clue). Often the singers seem to be caught in a

stage position that allows the orchestra to cover their voices. In a few

places the tapes seem to have deteriorated, leading to sudden jumps. At any

rate, the performance, while decent, hardly suggests that the unsatisfactory

sound is any tragedy. Gala gives star billing to Marion Lippert, a German

soprano whose career eventually took her to a couple dozen performances at

the Metropolitan Opera. The booklet essay quotes some reviews that praise her

stage demeanor in the role, which obviously cannot be evaluated in this

recording. Although not uncomfortable with the role’s challenges, she brings

little that is individual. Flaviano Labó ducks a couple of optional high

notes, but he sings a handsome, manly Calaf. Lydia Marimpietri earns the

usual happy applause for Liu’s melodic, sad arias. She is fine, but the

applause really should go to the composer. With the sound in its lamentable

state, making judgments about Napoleone Annovazzi and the theater orchestra

would be unfair.

Surprisingly, the audio on the 1931 La Scala Fedora prompts no

complaints, especially after that Turandot. This is not a live

recording, but the notes do not establish a provenance. Within a few seconds

of the opera’s beginning, the ears adjust to the limited spectrum, although

at places greater orchestral detail would be desired. That is due to the

naturalness and devotion conductor Lorenzo Molajoli brings to Giordano’s

score. Fedora at this date seems unlikely to ever attain a firm

place in the repertory, but heard here, it is possible to understand that at

one time, it seemed to have earned that distinction. A short opera with a

confusing, unconvincing libretto, it needs performers who truly believe in

it. There is true “golden age” glamour in the singing of Gilda dalla Rizza,

the Fedora whose revenge for her fiance’s death leads to her own suicide when

she realizes she has destroyed the loved ones of the killer she has come to

love. A tight vibrato and crisp enunciation give her performance a

conversational quality, although she certainly lets fly with some passionate

outbursts. The heart of the opera, a long duet in act two, finds her

well-matched with the Loris of Antonio Melandri. He gives out almost as many

sobs as he does ringing high notes, but in the red-blooded context of this

opera, his handsome voice can be excused some excess.

Surprisingly, the audio on the 1931 La Scala Fedora prompts no

complaints, especially after that Turandot. This is not a live

recording, but the notes do not establish a provenance. Within a few seconds

of the opera’s beginning, the ears adjust to the limited spectrum, although

at places greater orchestral detail would be desired. That is due to the

naturalness and devotion conductor Lorenzo Molajoli brings to Giordano’s

score. Fedora at this date seems unlikely to ever attain a firm

place in the repertory, but heard here, it is possible to understand that at

one time, it seemed to have earned that distinction. A short opera with a

confusing, unconvincing libretto, it needs performers who truly believe in

it. There is true “golden age” glamour in the singing of Gilda dalla Rizza,

the Fedora whose revenge for her fiance’s death leads to her own suicide when

she realizes she has destroyed the loved ones of the killer she has come to

love. A tight vibrato and crisp enunciation give her performance a

conversational quality, although she certainly lets fly with some passionate

outbursts. The heart of the opera, a long duet in act two, finds her

well-matched with the Loris of Antonio Melandri. He gives out almost as many

sobs as he does ringing high notes, but in the red-blooded context of this

opera, his handsome voice can be excused some excess.

The conclusion of Fedora takes up fewer that 15 minutes of the second disc. Once again, in filling out the side Gala wanders away from the stars of the main opera. Here the star becomes Lina Brusa-Rasa (although she gets no mention in the booklet, which does contain an admirably dense and detailed synopsis of Fedora, by Andrew Palmer). Lengthy highlights from an Andrea Chenier, also from La Scala in 1931, have the unfortunate effect of making the preceding Fedora seem even slighter. Bruna-Rasa is authoritative and affecting, and well-partnered by Luigi Marini as Chénier and Carlo Galeffi as Gérard. The lovers’ final duet might be worth the price of the set for some — urgently paced and thrillingly sung. After that, Gala still has room for arias from Mefistofele, Aida (actually the third act duet with the Amonasro of Galeffi), Cavalleria Rusticana, Manon Lescaut, and Tosca. Bruna-Rasa sings them all with both passion and taste, her very womanly tone mature only in the sense of ripeness and security.

So the Attila and Fedora earn recommendations to anyone interested in the operas or the singers. The Turandot would only find favor with any fans of Marion Lippert.

Chris Mullins

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Attila_Gala.png image_description=Giuseppe Verdi: Attila product=yes product_title=Giuseppe Verdi: Attila product_by=Samuel Ramey; William Stone; Linda Roark Strummer; Veriano Luchetti; Aldo Bottion; Giovanni Antonini, Orchestra e Coro del Teatro ‘La Fenice’, Gabriele Ferro (cond.)Live recording: Venice, January 23, 1987. product_id=Gala 779 [2CDs] price=$12.99 product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/album.jsp?album_id=146150

January 22, 2008

Torvaldo e Dorliska now on DVD

It is not often an opera goer gets to revisit a fondly remembered performance hoping the praiseworthy first impressions still ring true. Fortunately, the solid musical and dramatic values from the Rossini Opera Festival’s production of Torvaldo e Dorliska are still very much alive on this recently issued DVD taped in August 2006.

It is not often an opera goer gets to revisit a fondly remembered performance hoping the praiseworthy first impressions still ring true. Fortunately, the solid musical and dramatic values from the Rossini Opera Festival’s production of Torvaldo e Dorliska are still very much alive on this recently issued DVD taped in August 2006.

Echo de Paris: Parisian Love Songs 1610-1660

However, this may ultimately veil the reality that in cosmopolitan centers such as Paris, musicians of diverse nationalities were active and the range of styles “polyglot.” This diversity is one of the more prominent features of the excellent anthology, Echo de Paris: Parisian Love Songs 1610-1660. There are certainly the expected airs de cour by composers such as Pierre Guédron and Michel Lambert, and these strophic airs themselves are diverse: some are intimate and languorous, others show the clear influence of the dance. But there are also Spanish songs by the Frenchman Etienne Moulinié and Italian songs by visiting Italians Luigi Rossi and Francesco Cavalli. And underscoring the diversity is the large number of instrumental pieces here, much of which proceeds in Italian and Spanish accents.

The performances are superb. The Belgian tenor, Stephan van Dyck, sings with a free and beautifully natural sound, the forward placement of which makes the intimate scale especially effective. He has declamatory agility, as well, as in Moulinié’s “O Stelle homicide,” and he handles his ornamental graces deftly and with stylistic ease. Private Musicke—for this recording an ensemble of guitars, viols, lutes, and colascione—are wonderfully engaging in the “expatriate” music of the Italian guitarist, Giovanni Paolo Foscarini; their red-blooded rendition of his “Folia” is irresistibly brilliant, as is their imaginative, swinging performance of Luis de Briceno’s “Caravanda Ciacona.” Rhythmic verve of the highest order! But Private Musicke’s collaborative work in the vocal pieces is also unusually good. In Cavalli’s “Lamento di Apollo,” a moving lament with the expected ground bass propensities, the ensemble accompaniment is dramatically fluid and highly textured—quite memorably so—in ways that take one to the heart of spontaneous music making.

Echo de Paris may not give you exactly what you expect in an anthology subtitled Parisian Love Songs. With its rich array of national styles and instrumental pieces, it gives you much more, indeed, and all of it performed with a consummate sense of grace and flair. Musical cosmopolitanism at its best!

Steven Plank

image=http://www.operatoday.com/echo_de_paris.png

image_description=Echo de Paris

product=yes

product_title=Echo De Paris — Parisian Love Songs 1610-1660

product_by=Stephan van Dyck, Private Musicke, Pierre Pitzl (cond.)

product_id=Accent ACC 24173

price=$21.99

product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/album.jsp?album_id=150518

January 21, 2008

MAHLER: Symphonies 1-10

Recorded over two decades between 1984 and 2004, this set includes all ten of Mahler’s numbered symphonies, as well as the three-movement, original version of his youthful cantata Das klagende Lied and the late symphonic song-cycle Das Lied von der Erde, as well a selection of eight orchestral Wunderhornlieder. (Of the Wunderhornlieder, the set includes Der Schildwache Nachtlied; Verlor'ne Müh'; Wer hat dies Liedlein erdacht?; Wo die schönen Trompeten blasen; Revelge; Der Tamboursg'sell; Des Antonius von Padua Fischpredigt; and Ablösung im Sommer.) In addition, EMI includes a bonus track of Rattle’s 1995 performance of Der Abschied from Das Lied von der Erde from a live performance with the mezzo-soprano Anne-Sofie von Otter.

Those familiar with Rattle’s recordings of Mahler’s works will find no surprises in this collection, but the convenience of having all of the works in a single place is welcome, especially with the set priced lower than the individual releases. With such a specialist as Rattle, the collection makes it possible to appreciate the consistent precision and well-considered phrasing that the conductor brought to his interpretations of Mahler’s music. It is an impressive accomplishment that helped earn Rattle international recognition, especially with his recordings of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, which was less than familiar when he began the cycle. With such a successful recording as the Second Symphony, which was released in 1987 (and remains available as a single release), Rattle became known as a formidable interpreter of Mahler’s music.

In recording Mahler’s works Rattle made some choices that distinguish this set from others. He opted to record the original, three-movement version of Das klagende Lied, rather than Mahler’s revised version in two parts. With Das Lied von der Erde, his well-known recording with Peter Seiffert (tenor) and Thomas Hampson (baritone) is part of this set, with the use of two male singers the voicing, rather than the more typical use of mezzo soprano or contralto, and tenor. Yet his inclusion of Der Abschied with Anne-Sofie von Otter is welcome, and enthusiasts of Rattle’s Mahler recordings should appreciate its presence in this set.

Of Rattle’s recordings with EMI, several stand out in the modern discography of Mahler’s music, such as his interpretation of the Second Symphony, a solid reading with soloists Arlene Auger and Janet Baker, which was recorded in 1986. That particular release stands out among recent recordings for the attention Rattle gave to the details of score, including the nicely placed off-stage musicians that augment the soundscape. In addition, Rattle’s recording of Deryck Cooke’s performing version of Mahler’s unfinished Tenth Symphony has been well received, and it offers a solid reading of the torso.

While some quibble, at times, with Rattle’s interpretations, the consistent pacing that he conductor brings to each piece allows the score to be heard clearly and without some of the interpretative excesses that characterize other conductors. With the opportunity to review the body of Mahler’s symphonic works in Rattle’s hands, his faithfulness to the score emerges readily in all these recordings, most of which derive from live performances (as noted in the very useful program book included in the set). Rattle offers clear distinctions of tempo, as found at the beginning of the first movement of the Fourth Symphony, where the bells, Mahler’s erstwhile Schellenkappe, are, perhaps, slower than occurs in conventional recordings. Yet such deliberation sets up the quicker tempo that distinguishes the introductory bars from the principal theme and allows the reprise of the opening bars to serve as a transition when it recurs within the movement. At the same time, Rattle’s approaches Mahler’s shifting palette of orchestration with a sense of continuity that removes the pointillistic effects found in the notation itself. Again, the main theme of the first movement of Mahler’s Fourth Symphony is an excellent example of such timbral shifts, with the idea moving from the violins to the horns, back to the violins, then the flute and oboe, and the low strings, before resuming in the violins. This attention to the rendering the score is apparent in this movement and throughout the other recordings included in the set.

A similar approach occurs in Rattle’s interpretation of Mahler’s Fifth Symphony, which benefits from the fine playing of the Berlin Philharmonic with a work that ensemble has performed well under other fine conductors. As in other performances of Mahler’s music, Rattle’s pacing allows the discrete sections of movements to emerge clearly, and this is apparent in the Scherzo of the Fifth Symphony. While some might quibble with the some of the relatively slower tempos that result, the reading is clear and distinct, such that the accelerandos, when they occur, never distort the music ideas that they support.

With music that is more motivically connected, like the first movement of the Seventh Symphony, Rattle’s approach is effective in discriminating between the thematic content and the various secondary ideas that support it. His reading of the transition from the ending the introduction of the first movement of the Seventh to the beginning of its exposition is notable in this regard. As the movement continues, the fluid tempos are useful in characterizing the thematic groups that Mahler develops in increasingly intricate ways, and Rattle offers a convincing sense of the structure. Yet the telling point of any performance of the Seventh is the Rondo-Finale, and the recording is compelling from the start. The vibrant opening helps to propel the movement forward. While Rattle sets the various episodes apart with distinct shadings and nuances of tempo, the recurring refrain never flags. This allows Rattle to maintain the tension throughout the movement, with the final section offering a dramatic conclusion. The balance between brass and strings, a contrast that is characteristic of this movement, works well in retaining the details in the strings, while never allowing the brass to become the sole orchestral timbre. The energy never flags, and the Coda of the movement retains the fresh and exciting style with which it opened. While some of the other recordings do not include it, the applause at the end helps to confirm the excitement Rattle created in this performance.

In recording the entire cycle of Mahler’s symphonic works. Rattle worked with the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, except for three works: for Mahler’s Fifth Symphony and Deryck Cooke’s score for the Tenth, Rattle led the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra; and Mahler’s Ninth Symphony is with the Vienna Philharmonic, the ensemble associated with the premiere of the work. As to the soloists, the recordings included some of the finest singers available during the 1980s and 1990s. Late in their careers, Janet Baker and Arleen Auger were involved with Rattle’s impressive recording of Mahler’s Second “Resurrection” Symphony, and their contributions help to set that performance apart from others. For the Third Symphony, Birgit Remmert is the soloist, with Amanda Roocroft for the Fourth; and Simon Keenlyside sings the selections from Des Knaben Wunderhorn. The relatively recent (2004) recording of Mahler’s Eighth Symphony involves a remarkable international ensemble with Christine Brewer, Solie Isokoski, Juliane Banse, Birgit Remmert, Jane Henschel, Jon Villars, David Wilson-Johnson, and John Relyea. With the latter work, one of the latest ones in the set to be recorded, the quality of the soloists alone attests to the level of performers Rattle attracted in his explorations of Mahler’s music.

Those familiar with Rattle’s recordings of Mahler’s works will find this set to be a useful compilation of the entire set, and anyone who has not yet encountered Rattle in this venue will find much of interest. Released over two decades, Rattle did not operate under any kind of artificial timeframes that forced him to record the works in any particular order. While ten years separate the release of the Second and Third Symphonies, both recordings are convincing for the details that Rattle brought into each of them. Likewise, while one would expect the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra to perform all of Mahler’s works well under Rattle’s direction, the set benefits from the Berlin Philharmonic and the Vienna Philharmonic, which bear the conductor’s careful attention in their respective recordings.

As a set of Mahler’s symphonic works, this collection is quite attractive, and enthusiasts will want to have both Rattle’s set and the other one that EMI offers, the set of earlier recordings conducted by Gary Bertini. With Rattle’s set, though, some further documentation in the accompanying booklet would be welcome. In addition to the details about each performance, including recording dates and other details about the various sessions, the booklet includes transcriptions of Mahler’s sung texts in German, French, and English (for the hymn “Veni, creator spiritus,” the booklet includes the Latin text, with translations into the three modern languages).

Yet some details bear further explication. As laudable as it is to include the “Blumine” movement with the recording of the First Symphony, its placement as the first track of the work – even with Roman numerals indicating the order of the revised, four-movement version of the Symphony – bears further explanation. While the notes identify Das klagende Lied as the original version (in three movements), it would be useful to confirm that the recording of the First Symphony is indeed the revised version, with only “Blumine” stemming from the earlier form of the work. As to other details, the recording of the Sixth Symphony, which was made in 1989, follows the movement order as Mahler revised it, with the Andante preceding the Scherzo. While much has been made about the movement order among some Mahlerians, Rattle’s decision makes musical sense, and follows the tradition that dates to the premiere of the work.

At another level, the tracking of some of the more complex movements, like the Finale of the Second Symphony and both parts of the Eighth, is quite useful. Yet such a details approached to the tracking of the other movements would be useful, since it would not interrupt the flow of each performance. Such a detail would contribute to the set, which is otherwise quite fine. Of the modern recordings of the entire corpus of Mahler’s symphonies, this set is an essential one. With Rattle’s consistently solid interpretations, fine sound, and excellent playing, this set of Mahler’s symphonies will stand as a touchstone for years to come. Rattle is one of the finest interpreters of Mahler’s works, and this set stands as testimony of his accomplishments with this continually fascinating set of works that remain attractive to yet another generation of listeners. With this set Rattle has made an important contribution to the discography of Mahler’s music.

James L. Zychowicz

Madison, WI

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Mahler_Rattle.png

image_description=Gustav Mahler: Symphonies 1-10

product=yes

product_title-Gustav Mahler: Symphonies 1-10

product_by=Sir Simon Rattle, conductor.

product_id=EMI Classics 50999 5 00721 2 5 [14CDs]

price=$116.99

product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/album.jsp?album_id=175347

WAGNER: Parsifal

What may startle younger viewers accustomed to the contemporary shock-jock taste of German opera staging will be the reminder of how recent that all-conquering trend is: As late as the ’80s, Bayreuth would give you a forest and a temple where a forest and a temple were called for, a chorus of knights taking holy communion in that scene (by turns, those not singing are communing), with costumes of an almost embarrassing faux medievality in unsubtle, stained-glass reds and blues. Is this 1981 or a misprint for 1881, you may wonder — though as Parsifal had its world premiere in 1882, the answer to that should be obvious. This is a Parsifal very much aware of itself as Wagner’s apotheosis of the medieval religious ritual drama — there is no attempt at realism — higher matters are on the minds of everyone concerned.

Whether Wagner’s Gothic-revival religiosity appeals to you is not exactly the point; this production is not intended to convert but, like a medieval passion play, to proclaim mystical truths to those already converted. If you believe Wagner’s philosophic/religious mysticism takes a backseat to his musical achievement, you will have no difficulty enjoying this Parsifal. If Wagner’s mucking about with race and sacramental blood and sexual wounds gives you the willies, Parsifal is probably not for you in any case.

The set for the forest is a Klimtian forest; the Temple of the Grail five stage-high columns, curved to imply the ribs of a dome, curiously echoed in some rather threatening structures in Klingsor’s garden — as though to imply that Klingsor is attempting to create a sacrilegious parody of the Temple. The Grail manifests magically enough (though its glowing ruby heart is too obviously an electrical stage trick and would profit from distance) and the costumes make grand stage pictures from far off. None of the choral singers are individuals in this story anyway; they represent an archetypal mob, a backdrop to the symbolic drama in the foreground.

The acting of the principals in that foreground is stately and superb: either they, or the director, has put them through the meaning of every phrase of the libretto. The one unfortunate thing about director Brian Large’s fondness for close-ups is that we can see dry, empty hands when Kundry washes Parsifal’s feet and he baptizes her, also when Gurnemanz anoints him king of the Grail. We can also see that Randova has not bothered to make herself appear eldritch in Act I — which makes it difficult to understand why Amfortas and Gurnemanz do not recognize her as Klingsor’s houri, and why Parsifal does not know her when he meets her in Klingsor’s garden. Nor does she bother to die at the end of the show, though otherwise she follows Wagner’s careful directions in fixing her attention.

Horst Stein’s measured pace is most fulfilling: we are given a leisured march through this living ritual dream of a score, and tension arises through musical not active means. The singing is of a consistently high quality. What Siegfried Jerusalem lacked in sheer power as a heldentenor (and at Bayreuth, and in this kinder role, did not need), he makes up in thoughtful acting and phrasing: he is a puzzled seeker, not so frolicsome as many a Parsifal is played, but pensive from the first, a fool in his slow understanding but a mystic in his determination to make sense of what he sees and hears. The discovery of human pain and guilt that comes to him in Kundry’s kiss intensifies an awareness that was already present, lurking beneath the surface, and comes out in the final scene as Amfortas’s agonized face smooths itself out, and both agony and crown are transferred to the new Grail-king. (I also liked the touch of his having grown a beard between Acts II and III — and that it is already graying with his comprehension of the world.)

Randova, for whom Kundry was a signature role, sings with a luscious but little-varied tone in the long scene of attempted seduction. Hans Sotin is a Gurnemanz who reveals a temper even as he holds it in check, talking with the pages or with the nameless swan-killing youth or, sternly, to the mysterious knight (in, admittedly, a weird late-nineteenth century version of a Moorish caftan) who appears with a spear on Good Friday, but he always sings with majestic power. Wolfgang Brendel is more internally wracked than hysterical as Amfortas — indeed, that internality is a quality of all the characters in this staging: they are not so much wrestling with each other as with their own souls and internal demons. The well-named Leif Roar (did he ever sing with Peter Schreier?) scowls visibly and vocally as a human, rather than demonic, Klingsor. In terms of luxe casting, giving Titurel to Matti Salminen makes one gasp.

As ever with old Bayreuth recordings (or programs), it is entertaining to ponder where great careers began and led: Hanna Schwarz, a splendid singing actress who would win world-fame as the Fricka of Chereau’s Bayreuth Centennial Ring two years later, sings a page, a flower maiden and the Voice from Above in these performances; Toni Krämer, who would become a dull but competent Siegfried, is a Grail Knight.

John Yohalem

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Parsifal_Stein.png image_description=Richard Wagner: Parsifal product=yes product_title=Richard Wagner: Parsifal product_by=Eva Randova (Kundry), Siegfried Jerusalem (Parsifal), Bernd Weikl (Amfortas), Leif Roar (Klingsor), Hans Sotin (Gurnemanz), Matti Salminen (Titurel). Chorus and Orchestra of the Bayreuth Festival, conducted by Horst Stein. Production by Wolfgang Wagner. Video director Brian Large. Bayreuth Festival June-July 1981. product_id=Deutsche Grammophon 073 4328 [2DVDs] price=$45.99 product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/Drilldown?name_id1=12732&name_role1=1&comp_id=3426&genre=33&bcorder=195&name_id=56968&name_role=3January 20, 2008

Historic opera performances in Russian on Gala

Perhaps this trend died away with the greater ease of jet travel, or in a recoil from the ultra-nationalism which produced devastating wars. It certainly took a long time for Germany to begin offering, say, Verdi in Italian.

The trade-off is imperfect, however, as most singers sound their best singing in languages they are truly comfortable with. And what greater comfort than one's mother tongue? So three recent Gala releases of mid-twentieth century radio performances from Moscow of Italian and French repertory sung in Russian may at first seem like mere curiosities. Actually listening, however, may develop converts to the older style. Though initially the sharp, brusque sound of Russian may seem all wrong for Rossini or Delibes, the great singers captured here know their roles, and though these are not live performances, the sense of immediacy is palpable.

All the sets find room for extra tracks dedicated to one significant performer in each opera. Unsurprisingly, the Il Barbiere di Siviglia, recorded in 1953, focuses on the estimable tenor Ivan Kozlovsky. Besides his Almaviva in the opera, we also get on disc two his Gounod Romeo and in a particularly rare treat, a vocal version of Tchaikovsky dramatic overture to the Shakespeare tragedy, both sung with Yelisaveta Shumskaya's Juliet. Kozlovsky, in his early 50s at the time of the recording, retains his amazing upward extension, and ample evidence of that comes early in "Ecco ridente." Although all the recordings have decent sound, the hollow acoustic of the radio studio doesn't allow the tenor's tone to bloom, and it isn't always pleasing. But his technique still prompts respect.

The Figaro, Ivan Burlak, sings a rough but enjoyable "Largo al factotum." Vera Firsova's Rosina won't develop easily into the mopey countess of Mozart's Nozze. Her feisty, yet sweet, voice made your reviewer think of a Russian Victoria de los Angeles. In the singing lesson she performs a strong "Bel raggio lusinghier" from Semiramide. The great bass Mark Reizen growls humorously in a delightful "La Calumnia." The booklet essay, by the way, only provides biographies of Kozlovsky and Reizen, along with a brief synopsis of the plot and a few lines on the opera's premiere. Track listings for all three sets discussed in this review appear in the libretto's original language.

Both the Barbiere and the L'Italiana in Algeri feature a clunky piano to accompany the recitatives. Although the cast is less familiar, the L'Italiana comes across as just as fun. Gala's chosen focus here is Zara Dolukhanova, with the entire booklet essay providing information on her career. In the bonus tracks, she offers a darker but still passionate Rosina for "Una voce poco fa." Two strong excerpts from Semiramide suggest that if the complete performance exists, it should be released. Her Russian version of Meyerbeer's "Nobles seigneurs salut!" from Les Huguenots confirms what her Isabella in the main performance demonstrated: she could move that creamy voice as smoothly and quickly as required. Her supporting cast delivers solid performances, with the tenor, identified as "A. Nikitin," being overshadowed by his counterparts on the other sets.

Both the Barbiere and the L'Italiana in Algeri feature a clunky piano to accompany the recitatives. Although the cast is less familiar, the L'Italiana comes across as just as fun. Gala's chosen focus here is Zara Dolukhanova, with the entire booklet essay providing information on her career. In the bonus tracks, she offers a darker but still passionate Rosina for "Una voce poco fa." Two strong excerpts from Semiramide suggest that if the complete performance exists, it should be released. Her Russian version of Meyerbeer's "Nobles seigneurs salut!" from Les Huguenots confirms what her Isabella in the main performance demonstrated: she could move that creamy voice as smoothly and quickly as required. Her supporting cast delivers solid performances, with the tenor, identified as "A. Nikitin," being overshadowed by his counterparts on the other sets.

The third set leaves Rossini for Delibes's Lakme. The famous duet, "Viens, Malika," goes at a surprisingly snappy pace for Nadezhda Kazantseva, singing the title role, and Anna Maliuta. Kazantseva doesn't sparkle as some sopranos have done in the "Air des clochettes," though she has the notes. By the end of the set, a lack of variety in her tone has taken some of the exotic charm from her Lakme. Gala's choice for the spotlight here is the Gerard, tenor Sergei Lemeshev. He has more honey in his voice than Kozlovsky, but less individuality. The bonus tracks have sharper sound than the just adequate 1946 recording of the Delibes opera. Lemeshev's slight vibrato is loosening a bit in these tracks, though he sings a touching "Elle ne croyait pas" from Thomas's Mignon.

The third set leaves Rossini for Delibes's Lakme. The famous duet, "Viens, Malika," goes at a surprisingly snappy pace for Nadezhda Kazantseva, singing the title role, and Anna Maliuta. Kazantseva doesn't sparkle as some sopranos have done in the "Air des clochettes," though she has the notes. By the end of the set, a lack of variety in her tone has taken some of the exotic charm from her Lakme. Gala's choice for the spotlight here is the Gerard, tenor Sergei Lemeshev. He has more honey in his voice than Kozlovsky, but less individuality. The bonus tracks have sharper sound than the just adequate 1946 recording of the Delibes opera. Lemeshev's slight vibrato is loosening a bit in these tracks, though he sings a touching "Elle ne croyait pas" from Thomas's Mignon.

Considering the modest price Gala charges for its amply-filled sets, lovers of opera who want to explore the riches of a lost world of traditional opera performance should look for these sets. And Gala would do well to issue more, if more are to be found.

Chris Mullins

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Barbiere_Gala.png

image_description=Gioacchino Rossini: Il Barbiere di Siviglia (Sung in Russian)

product=yes

product_title=Gioacchino Rossini: Il Barbiere di Siviglia (Sung in Russian)

product_by=Ivan Burlak; Vera Firsova; Ivan Kozlovsky; Vladimir Malishev; Mark Reizen; Mihail Skazin; Nina Ostroumova; Ivan Manshavin, Chorus of the Moscow Radio; Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra, Samuel Samosud (cond.).Live recording: Moscow, 1953

product_id=Gala 768 [2CDs]

price=$12.99

product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/album.jsp?album_id=146147

Deutsche Grammophon budget opera sets

The theme seems to be iconic imagery in realistic photographs. For the fine Claudio Abbado-led La Cenerentola, the cover features a young washerwoman with wooden bucket and straw broom. She looks sad - hasn't anyone noticed her short skirt and cleavage-exposing blouse? Thankfully no model had to risk her life by posing amid the flaming pile of sticks for the Il Trovatore set.

Well, if such artwork catches the eyes of potential customers, their ears will be further rewarded with the performances contained in these sets. Abbado's elegant Cenerentola stars Teresa Berganza, who can sing sadly with great sweetness. When her big moment comes at the end of the opera, Berganza marries solid technique to refined joy. The bravura excitement of Cecilia Bartoli may be missed by some, but the Bartoli set, to the extent it is still available, remains at full price. Neither Bartoli nor Berganza have star tenors for the role of Don Ramiro, which has been sung with such beauty by Juan-Diego Florez, among current tenors. Luigi Alva on this 1971 DG set, while displaying command of the idiom, lacks tonal beauty. Paolo Montarsolo blusters as Don Magnifico, a character not easy to take on a recording. Renato Capecchi's Dandini slithers in and out of ensembles with appropriate slickness. The London Symphony orchestra and Scottish Opera Chorus make up for any perceived lack of Italian warmth with precision and style.

More than Italian warmth, fire burns through the Tullio Serafin Trovatore set. The cast listing in the booklet puts Ettore Bastianini's Conte di Luna first, and why not? His portrayal rages and aches with a passion that makes him much more than just the baritone villain. The "Il balen" alone makes this set precious, with gorgeous tone and supple, long-breathed lines. Sparks to light more than a few pyres fly when Bastianini meets the Azucena of Fiorenza Cossotto, near the start of her international career (the recording dates from 1962). Demonic in her low notes and fierce when she reaches high, she dominates the performance as only a truly great Azucena can.

More than Italian warmth, fire burns through the Tullio Serafin Trovatore set. The cast listing in the booklet puts Ettore Bastianini's Conte di Luna first, and why not? His portrayal rages and aches with a passion that makes him much more than just the baritone villain. The "Il balen" alone makes this set precious, with gorgeous tone and supple, long-breathed lines. Sparks to light more than a few pyres fly when Bastianini meets the Azucena of Fiorenza Cossotto, near the start of her international career (the recording dates from 1962). Demonic in her low notes and fierce when she reaches high, she dominates the performance as only a truly great Azucena can.

The ostensible leads both give worthy performances, if ultimately outshone by both the stars mentioned above in this recording, and by other singers in their roles on other versions. Antonietta Stella's lovely soprano sometimes threatens to spread at the end of long lines or high-flying passages. Ultimately her very feminine sound carries her through. Carlo Bergonzi gives a more bel canto reading of Manrico than is typical. The character is a troubadour, after all, and Bergonzi makes it clear that Manrico can sing quite beautifully. He does fire up the engines for "Di quella pira," with an understandable if amusing delay before firing off the climatic high note at the aria's end.

Serafin proves again his mastery of Verdi, and the chorus and orchestra of La Scala perform with their expected conviction. The overly bright recording, however, lacks any sense of dramatic space.

Both sets come with detailed track listings that include plot summaries of the action at key moments, in English, French and German. Your reviewer could find no word of a link to an online libretto in the booklet. So these sets can be best recommended to opera fans who already own sets with more complete packaging. Both offer ample musical reasons for adding them to any collection.

Chris Mullins

image=http://www.operatoday.com/DG_Cenerentola.png

image_description=Gioacchino Rossini: La Cenerentola

product=yes

product_title=Gioacchino Rossini: La Cenerentola

product_by=Berganza, Guglielmi, Zannini, Alva, Capecchi, Montarsolo, Trama, Scottish Opera Chorus, London Symphony Orchestra, Claudio Abbado (cond.)

product_id=Deutsche Grammophon 477 5659 [2CDs]

price=$16.49

product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/album.jsp?album_id=146031

STRAUSS: Der Rosenkavalier

Carlos Kleiber, in a live stage recording, fronts a top-notch ensemble in a gorgeous staging that seamlessly weds the rollicking humor to misty-eyed sentimentality and romance.

The 2004 Salzburg Festival Rosenkavalier, directed by Robert Carsen, takes its place at a very distant and frigid polar extreme from the warmth of those earlier incarnations. Sets and costumes boast as much expensive extravagance, but in the service of a concept that seems to originate in a loathing of the characters and the story. As Gottfried Kraus's excellent booklet essay relates (as translated by Stewart Spencer), Carsen and set designer Peter Pabst place the opera in "the decadent, valedictory atmosphere of the dying Hapsburg monarchy."

For act one, the long Salzburg stage is split into three rooms, with servants traipsing through. The realization impresses visually, but it also puts a distance between the characters. Act two takes place in the Faninal's dining hall, with most of the action played before an extended table that could seat dozens and dozens of guests. In a touch more out of a Zefferelli production, Octavian makes his entrance on a steed. After that equine interpolation, the setting quickly returns to its austere dictates. Act three is not just a disreputable inn, but a house of prostitution, with much nudity and even simulated copulation. The innkeeper is a drag queen. Now, why would Baron Ochs's proposed seduction of a maidservant, before his marriage, so shock people who cavort in such an establishment? No matter. By this point, the staging is not about the characters anymore, and more a picture of a dissolute, arrogant society. Carsen caps this off by using an adult Mohammed, then finishing the evening with the appearance of a severe man in military get-up - the Field Marshall himself? The luscious haze of the trio and sparkle of Mohammed's music is poisonously clouded by the image.

Act two, somewhat surprisingly, comes off best, with Franz Hawlata really hitting his comic stride. Adrianne Pieczonka never really gets to settle into the regal self-involvement of the Marschallin. Angelika Kirchshlager remains a mostly feminine Octavian throughout, especially in her reverse "drag" appearance in act three, where she is directed to act as a slut whose prim objections to the Baron's seduction are clearly only perfunctory. Miah Perrson, even in this unconventional staging, remains a conventional Sophie. In his brief appearance, Piotr Beczala brings handsome tone even to the high-lying passages of the Italian Singer's aria.

Semyon Bychkov leads the orchestra in a sharp, if unsubtle, reading of the score. Carsen's Rosenkavalier, then, turns the opera's chuckles into grim snorts, and its romance into transparent delusion. While stunning to look at it many ways, the production is very far from a pretty one. If that is the kind of Rosenkavalier any Opera Today reader has been awaiting - the wait is over.

Chris Mullins

image=http://www.operatoday.com/TDK_Rosenkavalier.png

image_description=Richard Strauss: Der Rosenkavalier

product=yes

product_title=Richard Strauss: Der Rosenkavalier

product_by=Adrianne Pieczonka, Angelika Kirchschlager, Franz Hawlata, Franz Grundheber, Miah Persson, Konzertvereinigung Wiener Staatsopernchor, Wiener Philharmoniker, Semyon Bychkov, conductor. Robert Carsen, stage director, Recorded during the 2004 Salzburger Festspiele.

product_id=TDK DVWW-OPROKA [2DVDs]

price=$34.99

product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/Drilldown?name_id1=11683&name_role1=1&comp_id=2927&genre=33&bcorder=195&label_id=4145

Die Walküre at the Met

A dearth of major Wagnerian voices might be, has been, blamed … but other companies do better … or so it seems to us New York Wagnerians.

The current revival of Die Walküre, always the most popular of the Ring operas, is impressively satisfying: none of the singers are bad, some of them are great, only one of them is even stout (Stephanie Blythe, who, however, sings like the goddess she plays and moves in a stately, never clumsy, manner), while an unfamiliar hand on the podium brings out some unfamiliar colors from the depths of this shimmering score.

The weakest link in the cast was Clifton Forbis, the Siegmund — his gravelly, forced quality, an ill-supported top, no lyricism in the “Winterstürme,” all made this a woeful Wehwalt. The only time he sang with much power was the cry of “Walse! Walse!” — something about this shout seemed to align his throat properly for the first — and last — time all night. In rather striking contrast, Adrianne Pieczonka, a slim, girlish Sieglinde, sang with a full tone a bit beyond complete control, and was underpowered only in the “triumph of woman” explosion in Act III. She might be starting on the road to a major interpretation; Forbis, however, seems simply miscast.

James Morris had a Mozart and bel canto background when he first essayed Wotan twenty years ago — and was then widely expected to fail. Instead, he thrilled all ears, and he has owned the part ever since. (Could his bel canto experience be responsible?) Wobbles in his Hans Sachs last year made me wonder if his Valhalla sun had set, but he was in fine voice during the second performance of the run of Walküres, a little dryer than the lustrous hue of old, no doubt, but wobble-free, in command of the full range of notes and dynamics, and an experienced actor of this figure who attains tragic stature through tardy self-knowledge.

Lisa Gasteen, a star of Rings from London to Vienna to Adelaide, made her first essay at the title role of this opera in New York. She sang, it was announced, with a sore throat, and one would like to credit that for the general weakness of her voice above the staff that began with her first war-cry and continued to the end of the night. But Wagner was not a high-note composer, and the rest of her voice was lovely, beautifully produced, full of deep emotion.

A scene from Wagner's “Die Walküre” with Adrianne Pieczonka as Sieglinde and Clifton Forbis as Siegmund.

A scene from Wagner's “Die Walküre” with Adrianne Pieczonka as Sieglinde and Clifton Forbis as Siegmund.

She also cuts a handsome figure and bounds about the rocky sets with youthful athleticism, as a hard-riding warrior goddess ought to — but how many do? In the orchestra, I had doubts about the size of the voice when it came to filling the Met, and friends who sat upstairs shared them, but this was an honorable attempt that gave much pleasure. If her health on Monday is not the reason for her weak top, however, she is hardly the woman to sing the higher Brünnhilde of Siegfried. This experience of her made one interested in hearing her under optimum circumstances and in many roles. (A revival of Frau ohne Schatten would suit her nicely — she’s sung both soprano leads in Germany.)

A scene from Wagner's “Die Walküre” with (from left) James Morris as Wotan, Stephanie Blythe as Fricka, and Lisa Gasteen as Brünnhilde

A scene from Wagner's “Die Walküre” with (from left) James Morris as Wotan, Stephanie Blythe as Fricka, and Lisa Gasteen as Brünnhilde

Among the smaller roles, Mikhail Petrenko was especially striking — joining the lengthy list of Hundings whom one wishes had more to do, or big juicy roles in something else in the very near future. (Whatever became of Stephen Milling?) Kelly Cae Hogan, a singer new to me, was first off the mark among the valkyries, and one wished her war-cry, clear and focused and bright, had somehow been substituted for Gasteen’s cautious one; the rest of the gang were also happy choices.

The stage direction seemed to have been tightened, and was especially well synchronized at such tricky moments as Siegmund’s death (and Sieglinde’s flight) and the valkyrie ensembles. The diction all around was exceptional, precise without being intrusive. Lighting for this production seems to be getting steadily dimmer — which makes things like the magic fire all the more effective.

Lorin Maazel’s approach to Wagner was vivid and the pace snappier than we are used to, which rather heightened the excitement of a happy occasion. As at every great Wagner performance, one heard things, instrumental colors, one had never noticed before. Consider, for instance, Wagner’s use of kettledrums for everything but beating time: enhancing this, emphasizing that, pointing words or other instruments, a sudden insertion of ominous texture in the midst of a leitmotiv associated with things not ominous — insofar as anything in the Ring is free from shadow.

John Yohalem

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Walkure-_Pieczonka___Forbis.png image_description= product=yes product_title=Richard Wagner: Die Walküre product_by=Brünnhilde: Lisa Gasteen; Sieglinde: Adrianne Pieczonka; Fricka: Stephanie Blythe; Siegmund: Clifton Forbis; Wotan: James Morris; Hunding: Mikhail Petrenko.Metropolitan Opera: conducted by Lorin Maazel. Performance of January 14. product_id=Above: Adrianne Pieczonka (Sieglinde) and Clifton Forbis (Siegmund)

All photos by Marty Sohl courtesy of The Metropolitan Opera

Lamentazioni per la Settimana Santa

The birth and development of the oratorio, for instance, is a rich example of this, with Roman prayer halls harnessing contemporary theatrical music to evangelical ends. And certain liturgical contexts also seemed to invite modern expressive touches. The triduum sacrum, Thursday, Friday, and Saturday of Holy Week, is a case in point; Tenebrae, the Office of Matins for these days, focuses on the poignant texts of the Lamentations of Jeremiah , the affective extremes of which were very well suited to the stile moderno. Much as the operatic lament became popular in the seventeenth century for its affective depth, so too did settings of the Lessons of Tenebrae.

The recording Lamentazioni per la Settimana Santa features a composite of Tenebrae settings by Roman composers, such as Carissimi, Frescobaldi, and Giovanni Francesco Marcorelli, all preserved in a single Bolognese manuscript (Civico Museo Bibliografico Musicale Q 43). Much of the music is recitative in character, some of it evocative of chant, though the Hebrew letters that preface the scriptural passages are often sublimely lyrical. And on occasion, the treatment of specific words will elicit a madrigalian touch. Carissimi’s music here is somewhat restrained and controlled; Marcorelli’s language is more extravagant in its musical rhetoric and expressive idiom; but all of the settings manifest the close synergy of affection and music that was fundamental to the new musical style. The settings then are intensely expressive, though rarely expansive. One exception might be one of the anonymous works where the Hebrew letters, instead of only prefacing the verses, come back internally as ritornelli, allowing for a more developed landscape.

The performances are impressive, rich in style and sensuous sound. Soprano Maria Cristina Kiehr sings with notable flexibility and pliancy—the wafting taper of some of her notes is simply stunning—and her tone quality seems almost paradoxically to be both pure and rich in body at the same time, somewhat reminiscent of the Spanish soprano, Montserrat Figueras. The contributions of Concerto Soave, a continuo ensemble of viol, harp, lute, lirone, and claviorganum, are strong. Certainly the richness of the sound owes much to the instrumental palette. And the accompaniment of the lirone—a bowed viol played chordal—is simply sublime. The size and variety of the ensemble allow for a number of different configurations, an “orchestrational” opportunity that is used to good effect here, as well.

The recording includes several instrumental pieces, democratically featuring the different players of keyboard, harp, lute, and viol. The keyboard “interlude,” a toccata by Michelangelo Rossi, gives the rare chance to hear the unusual sound of the composite instrument, the claviorganum. The claviorganum combines both harpsichord and organ in one instrument; here, through the use of two manuals, one can play florid passages on the harpsichord while rendering chordal accompaniment on the organ, well serving the structure of Rossi’s piece.

In Lamentazioni per Settimana Santa we hear the stunning musical echoes of the rich devotional life of seventeenth-century Rome. Brought to life through performances of great beauty, this is a recording to savor.

Steven Plank

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Lamentazioni.png

image_description=Lamentazioni per la Settimana Santa

product=yes