February 25, 2008

Puccini Gold

Besides demonstrating how easily the great composer's operas can be raided for two hours of inspired lyrical treasures, Decca's compilation highlights the stars it apparently regards as its greatest marketing winners. Six names appear above the CD title on the cover in large font: Pavarotti, Netrebko, Bocelli, Villazon, Fleming and Domingo, and their handsomely posed portraits adorn the cover. In smaller print at the bottom of the front cover reside stars such as Jose Carreras, Angela Gheorghiu, and Roberto Alagna. Their portraits are found on the back cover. One name on the front cover that may prove elusive to the star-conscious is Kaufmann, as in Jonas Kaufmann, whose debut CD Decca has only been recently released. He joins Kiri te Kanawa in making the front cover listings without earning a space for his photo, front or back.

The two discs feature many indisputably great selections, including several prized cuts from the complete opera recordings of Madama Butterfly and La Boheme that Herbert von Karajan led. Zubin Mehta's Turandot gets space, although strangely Joan Sutherland's phenomenal "In questa reggia" is bypassed for her somewhat less impressive "Senza mama" from Suor Angelica. Unsurprisingly, Luciano Pavarotti starts the collection with "Nessun dorma," and both of Liu's arias, as sung by Montserrat Caballe, appear on CD two.

While it is understandable that Decca wants to feature its more recent catalog, those selections are among the less impressive. Renée Fleming comes across as mannered in the ubiquitous "O mio babbino caro," although her "Chi il bel sogno di Doretta" is indisputably lovely. Rolando Villazon and Anna Netrebko ham it up a bit too much in "O soave fanciulla," and conductor Nicola Luisotti enables their act with fussy pacing. The darker tenor of Kaufmann makes for a gruff Rodolfo in "Che gelida manina," but it is an interesting turn on the arguably overly familiar aria. Opera snobs will turn up their noses at Andrea Bocelli's "Addio, fiorito asil," but it is a fine selection for his voice. However, Decca could easily have gone back just a couple years for an even finer version by tenor Joseph Calleja. Apparently Decca has already forgotten about him.

In a nice touch, Decca includes some instrumental selections conducted by Riccardo Chailly, with the rare but lovely "Crisantemi" and a potent intermezzo from Manon Lescaut. Otherwise the two CDs survey almost exclusively the tenor/soprano repertoire. Surely Scarpia could have made an appearance, or even Sherill Milnes's Rance, heard briefly in Placido Domingo's "Ch'ella mi creda" from La Fanciulla del West.

The set's real demerit lies in the editing. The orchestral introduction to "Recondita armonia," for example, has been cut, so that the track abruptly begins with Jose Carreras singing the title words. Then after the aria has concluded, the performance continues with some of the Sacristan's lines, before ending as suddenly as it began. Similarly, after Gheorghiu's "Si, mi chiamano Mimi" ends, we get the dialogue leading up to "O soave fanciulla," with the music ending just where the duet would commence.

At any rate, most confirmed Puccini lovers have probably long ago assembled their favorite music as performed by their favorite singers. A collection such as Puccini Gold is probably for those who have had just enough of a taste of Puccini to know they want to explore the music further. Despite the editing glitches and the arguable choices of artists, those purchasers should be happy with Puccini Gold.

Chris Mullins

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Puccini_Gold.png

image_description=Puccini Gold

product=yes

product_title=Puccini Gold

product_by= Luciano Pavarotti, Montserrat Caballé, Carlo Bergonzi, Mirella Freni, Renée Fleming et al.

product_id=Decca 028947593799 [2CDs]

price=$19.99

product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/album.jsp?album_id=185152&album_group=12

Salome at Covent Garden

Its main set is a pale, dank, tiled basement – the excesses of the banquet in the palace above are glimpsed on an upper level which sits just below the proscenium arch. The 'below stairs' angle may be one of director David McVicar's trademark devices, but here it is evocative of a sewer, an underworld, a space suspended between this world and Hell. Designer Es Devlin has exercised faultless attention to detail in bringing this concept to life.

The people who inhabit this place are as devoid of human emotion as the animal carcasses we see hanging in one of the basement's doorways. Following Narraboth's suicide, the others make a point of picking their way around his fresh corpse as if to demonstrate just how little his death matters to them.

Nadja Michael's Salome is credibly young and nubile, slinky, poised, if not really sexy. She produces a huge sound considering her physical build, and it gleams on top when it is in tune, though she does have a few intonation problems. Her fixation with Jokanaan is quite understandable, as Michael Volle dominates the stage in both voice and presence even when he cannot be seen.

The Dance of the Seven Veils is not done as a conventional striptease but as a dream interlude after the modern fashion. It is a subtly disturbing fantasy sequence, where the tiled walls give way to black depths with cinematic projections which suggest Herod's sexual obsession with Salome from early childhood. This unspoken suggestion of Salome's lifetime of rape by her stepfather makes sense of her scheme to destroy both Jokanaan and Herod himself. At the end of the dance, Salome leads Herod off for one final tryst – this time on her terms – before making her fatal demand.

Robin Leggate was a late substitute as Herod. If he lacked the physical presence and vocal weight of Thomas Moser, who he replaced, he certainly found an element of black comedy in his petty, bickering interchanges with Daniela Schuster's Herodias.

Against the murky grey-white background, there is an emphasis on the luridness of Herod's court – represented by Herodias in her glittering turquoise gown – and of Jokanaan's murder, when the naked executioner emerges from the cistern dripping with the prophet's blood. However, Salome herself is a pale sylph in a glistening white dress, and Herod's fantasies of her during the Dance of the Seven Veils have a crisp monochrome purity. From Herod's perspective, her horrific request for Jokanaan's head comes as a complete surprise from someone he sees as a perfect specimen, an alabaster ornament.

(left to right) Michael Volle (Jokanaan), Joseph Kaiser (Narraboth) and Nadja Michael (Salome)

(left to right) Michael Volle (Jokanaan), Joseph Kaiser (Narraboth) and Nadja Michael (Salome)

And as this beautiful creature's white slip and limbs become drenched in Jokanaan's blood, the assembled court – at first averting their eyes in revulsion – gradually turn towards her and become transfixed on the spectacle, just as Herod's and Narraboth's eyes had always been inexorably drawn in her direction.

Orchestrally, the standards were generally high; Philippe Jordan certainly has an understanding of how to bring out the horror in Strauss's opulent score, though some untidy brass playing took the shine off the texture.

Ruth Elleson © 2008

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Salome_015.png image_description=Nadja Michael (Salome) [Photo by Clive Barda courtesy of the Royal Opera House] product=yes product_title=Richard Strauss: SalomeRoyal Opera House, Covent Garden, February 21, 2008 product_by=Above: Nadja Michael (Salome)

All photos by Clive Barda courtesy of the Royal Opera House

VINCI: La Partenope

Music composed by Leonardo Vinci. Libretto by Silvio Stampiglia.

First Performance: 1725, Teatro San Giovanni Grisostomo, Venice.

| Principal Characters: | |

| Rosmira, Princess of Cyprus | Soprano |

| Partenope, Queen of Partenope (later Naples) | Contralto |

| Arsace, Prince of Corinth | Soprano |

| Armindo, Prince of Rhodes | Tenor |

| Emilio, Prince of Cuma | Mezzo-Soprano |

| Ormonte, Captain of Partenope's Guard | Tenor |

Background:

Partenope (or Parthenope) appears in Greek mythology and classical sources as one of the sirens who taunted Odysseus. One version has her throwing herself into the sea because her love for Odysseus was not returned. She drowns. Her body washes ashore at Naples, which was called Partenope after her name. From this, Silvio Stampiglia created a fictional account where Partenope appears as the Queen of Naples. According to Robert Freeman:

[T]he libretto for Partenope . . . [was] first set for performance in Naples during 1699 with music by Luigi Mancia, and produced all over Italy in more than a dozen versions with music by a variety of composers . . . [The libretto involves] a young lady named Rosmira, once betrothed to and then deserted by Arsace, now a suitor of Partenope, Queen of Naples, where the drama takes place. Early in the libretto, Rosmira, disguised as a man, charges Arsace with infidelity and defies him to redeem his honor by promising never to reveal her identity. After Arsace promises, Rosmira taunts him before the court, then challenges him to a duel, which Arsace quite naturally tries to evade. But in the final scene Arsace hits upon a solution. He agrees to the duel, but on condition that it be fought with combatants stripped to the waist. . . Rosmira admits her identity and there is no duel.Notes, Vol. 28, No. 2 (Dec., 1971), pp. 216-217.

Click here for the complete libretto.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/partenope.png image_description=Partenope audio=yes first_audio_name=Leonardo Vinci: La PartenopeWinAMP, VLC, FooBar first_audio_link=http://www.operatoday.com/Partenope_Vinci.m3u product=yes product_title=Leonardo Vinci: La Partenope product_by=Partenope: Sonia Prina

Arsace: Roberta Invernizzi

Emilio: Lucia Cirillo

Armindo: Makoto Sakurada

Ormonte: Rosario Totaro

Rosmira: Maria Grazia Schiavo

Capella della Pieta de' Turchini

Direttore: Antonio Florio

Live Performance: 10 July 2004, Festival International d'Opéra Baroque de Beaune

February 22, 2008

Carmen, The Metopolitan Opera

Shrouds mantle the vaults of heaven; the gilt and sparkle of the opera house seem to mock the gray mood.

Let me explain why I was eager to hear Olga Borodina’s Carmen again: She starred in a close-to-perfect series of performances of the opera a few years ago, ably partnered by Roberto Alagna (such a piteous child when he finally got the message in the last act, “Tu ne m’aimes plus?” and then leaped for her throat) and Rene Pape (the sexiest of all possible toreros).

At that performance I felt I was seeing Bizet’s Carmen for the first time — seeing the character as Bizet conceived her, as she is almost never performed. She was not a sexpot. She couldn’t be bothered to deal with masculine fantasies. She walked in on her way to work, sneered at the idiotic, amorous male chorus, sang a song (why not? She had a great voice), noticed the pretty soldier on the sidelines and tossed him a flower — for the hell of it. She was a Carmen who didn’t care if we were staring or not. Most Carmens work far too hard — they shove their poitrines in every face, they hoist their dresses to display their legs, their world is all about sex. Not Borodina — her world was all about doing what she wanted to, with whoever cared to join her — and snapping her fingers at those who would not. In Act II, when Frasquita and Mercedes pushed themselves in Escamillo’s face, this Carmen sang “L’amour,” pensively (and in that low, dusky, impossibly sensuous Borodina voice) — she wasn’t singing about love to attract Escamillo’s attention, she was brooding about it to herself. And that was just what did attract his attention. Was Jose going to kill her? All right — he was going to kill her. But he would not keep her from being herself out of something so alien as fear.

That was Carmen. A real, a credible, an adorable Carmen — precisely because she did not care if we adored her or not. She was herself. And with Borodina’s voice.

But last week something fell on Borodina’s foot, and she did not sing on February 19.

Her replacement was Nancy Fabiola Herrera, a singer unknown to me. Herrera’s Carmen was no last-minute exercise; it’s a finished portrait, everything in place, comfortable on the enormous Met stage, no matter how many choristers and herds of farm animals Franco Zeffirelli clutters it with. Not really a surprise, as Ms. Herrera was scheduled to take the role next week. Its nuances were hardly strange to her.

Marcelo Álvarez as Don Jose (Photo by Beatriz Schiller courtesy of The Metropolitan Opera.)

Marcelo Álvarez as Don Jose (Photo by Beatriz Schiller courtesy of The Metropolitan Opera.)

She is a handsome young woman with a handsome voice, a pleasing quality in the lower notes and no break. She can certainly sing it, plus she can act and dance, and plays castanets as well as any Carmen since Teresa Berganza. (I’m told she has zarzuela training.) But her Carmen was a cliché: the spitfire flirt. She sang her arias prettily enough, but she was trying to please. Of a deeper, more self-conscious Carmen there was no sign until the fortune-telling of Act III, when she withdrew into herself. She was not so pretty any more, a dark and brooding quality came over her voice, she seemed to withdraw into herself and become one with the music; the opera began to seem to be her story.

Just then, however, she came up against a rival worthy of her steel — Krassimira Stoyanova, one of the great singing actresses of our time, whom the Met has squandered on the role of Micaela. (She will be our Donna Anna next year, however; I’m expecting fireworks.) Stoyanova sang the aria beautifully, but it was her confrontation with Jose and Carmen that made us sit up straighter: she wasn’t just defeated in love, she was angry at what lust had done to the man she loved, angry at Carmen (at whom she barely deigned to look) and furious at Jose. These lines are throwaway; in most performances one hardly notices them; in this Carmen all three performers were electric, their confrontation crackled.

These later acts were Marcelo Álvarez’s best as well. A burly man, he is not flattered by Jose’s uniform; as a thuggish smuggler, whatever Carmen might say, he seems perfectly at home, capable of any violence. This made up for a weak, ill-supported account of the Flower Song. Lyric moments are not, evidently, Álvarez’s forte; when he must be passionate, he is an interesting singer. Someday, not too far off, an Otello — but just now, I wouldn’t want to hear him in the love duet of that opera until he has worked on his lyric phrasing. Just now, when he tones down the passion in order to plead, he merely sounds weak.

His madness in the final scene was less pitiable, less human than Alagna’s, but effective. He and Herrera seem to have worked on this: they did a neat little bullfighting dance, a paso doble as it were, when he came at her with his knife and she dodged, fearlessly and, with a glance of contempt, walked past him — exposing her back — daring him to do his worst. It was a thrilling conclusion, and drew a standing ovation.

Lucio Gallo was the least impressive toreador I can recall, and not merely because he is too fat to evade a slow, blind yak — his singing is without personality, pretty notes phoned in. You did not notice him; you were surprised that anyone noticed him. He has no stage gifts, and the Met appears to have stuck him in at the last minute, when they changed a run of Hoffman for Carmen late last spring, hoping it would all fall into place. I’m guessing the Met also did not think through the casting of seven-foot-tall John Hancock as Dancaire opposite four-foot Jean-Paul Fouchécourt as Remendado — I exaggerate, slightly — but they seized the opportunity for some delicious Mutt-and-Jeff muggery. When they nudge each other, as comrade smugglers will, speculating on the same female rear end, what different acts (we ponder) do they imagine performing? Jeffrey Welles sang a worthy Zuniga. (Why not give him Escamillo? Or Hancock? Neither has the physique du role, but they could both put it over with flair.)

Emmanuel Villaume conducted; the opening prelude was unsatisfactory, all crash-bang-boom and cliché. The preludes to the other acts were more satisfactory, more breathable, and he was gracious to the singers, both familiar and (in Ms. Fabiola’s case) unfamiliar.

The Zeffirelli Zoo Story production (horses, burros, dogs) holds up well, but I object to his having set the opera — three acts of which are supposed to take place in the riverside plain of Seville — in mountainous Granada, solely because the sets (especially for Act II) thus become more scenic. Let Spain be Spain.

John Yohalem

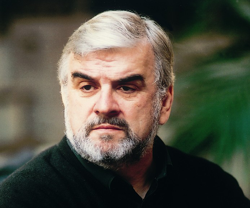

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Carmen_Herrera.png image_description=Nancy Fabiola Herrera as Carmen product=yes product_title=Georges Bizet: CarmenThe Met: February 19, 2008 product_by=Carmen: Nancy Fabiola Herrera; Don Jose: Marcelo Álvarez; Micaela: Krassimira Stoyanova; Escamillo: Lucio Gallo. Production by Franco Zeffirelli. Conducted by Emmanuel Villaume. product_id=Above: Nancy Fabiola Herrera as Carmen

Photo by Marty Sohl courtesy of The Metropolitan Opera.

Tito Manlio at the Barbican, London

Neil Fisher [Times Online, 21 February 2008]

Neil Fisher [Times Online, 21 February 2008]

On the eve of the latest Baroque exhumation in the Barbican, the scholar who oversaw the new edition of Vivaldi's 1718 opera had some advice. “Should you lack the will to delve into the convoluted text,” she wrote in a national newspaper, “have no fear; at this early stage in the history of opera, you can go without.”

'Tosca' is so intricately constructed it's uncuttable

By R.M. CAMPBELL [Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 21 February 2008]

By R.M. CAMPBELL [Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 21 February 2008]

Chris Alexander has spent a lifetime in the straight and lyric theater but never staged Puccini's great melodrama "Tosca" until Speight Jenkins, general director of Seattle Opera, asked him to. The production opens this weekend at McCaw Hall.

Austria to auction late soprano's estate for charity

VIENNA (AFP) — The estate of Elizabeth [sic] Schwarzkopf, the legendary German soprano who died in 2006, will go under hammer here next month, with the proceeds to go to charity, the Vienna-based auction house Dorotheum said Thursday.

VIENNA (AFP) — The estate of Elizabeth [sic] Schwarzkopf, the legendary German soprano who died in 2006, will go under hammer here next month, with the proceeds to go to charity, the Vienna-based auction house Dorotheum said Thursday.

Leonie Rysanek Live Recordings 1955-1991

The first disc covers a wide range of composers, from Tchaikovsky through Verdi and Puccini, to Wagner. The second disc focuses on the operas of Richard Strauss, perhaps the composer with which Ms. Rysanek was most closely identified.

The enclosed booklet features two articles by Peter Dusek. The first, briefer one covers the specific performances included in the set, while the longer essay amounts to a biography of the singer's professional career. Not too long into the first of these articles, Dusek, as translated by Steward Spencer, refers to Rysanek and her partner in the Eugene Onegin final duet as "two great singing actors." For those fortunate opera lovers who attended Ms. Rysanek's live performances, the recordings on this set will undoubtedly bring back many memories of her imposing, incisive theatrical abilities. But as an audio experience, only so much of Ms. Rysanek's acting ability can be discerned here. And frankly, whether it is the Tatiana of 1955 or the Kostelnicka of 1991, Ms. Rysanek's voice was not favored by recording equipment. At least some of the drama of her top notes extends from the evident strain of accomplishing them. The body of the voice suggests substantial weight, with a slight tendency to feel just under the note. Although she appears to have had great affection for Italian opera, her Aida, Tosca, and Santuzza, as heard here, would probably be best enjoyed by fans tuned into her dramatic perspective.

Her 1985 Ortrud, however, finds her resources well-matched to the demands of the role, as does her Kundry. There are many such moments on the second disc of Strauss excerpts, including a truly scary final scene from Salome. Rysanek's Chrysothemis, to Birgit Nilsson's Elektra in 1965, has more edge and tension than is typical in performers of the role, which arguably makes the ties between the two sisters stronger.

Perhaps the key track here for understanding Rysanek's artistry is the Marschallin's act one monologue from Der Rosenkavalier. Rysanek's coloring of words and phrases creates a vivid portrait of the woman's state of mind, proud and yet openly emotional. Nonetheless, over the 25 minutes of the scene, your reviewer's ears tired of Rysanek's tone and the sense that any extended note never quite hits the center of the pitch.

Again, Dusek's booklet essay gives the point of view of so many who cherished this artist, and it is surely for them that Orfeo has produced this handsomely packaged set, with its many enjoyable photographs of Rysanek in her key roles. If such fans have not already acquired this set, they are urged to seek it out.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Rysanek_live.png

image_description=Leonie Rysanek Live Recordings 1955-1991

product=yes

product_title=Leonie Rysanek Live Recordings 1955-1991

product_by=Leonie Rysanek et al.

product_id=Orfeo d'Oro 696072 [2CDs]

price=$16.99

product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/album.jsp?album_id=168909

February 20, 2008

Sephardi singer keeps father's ancient passions and language alive in song

[The Age, 21 February 2008]

[The Age, 21 February 2008]

From a deep and spiritual history come songs of relevance to every era, writes Michael Dwyer.

YASMIN Levy's musical journey started in 1492, in the purges of the Spanish Inquisition. It was the year Catholic monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella sent Christopher Columbus west in search of wealth and glory, and hundreds of thousands of Jews fleeing in every direction under threat of extermination.

Giulio Cesare, Amsterdam

By Richard Fairman [Financial Times, 20 February 2008]

By Richard Fairman [Financial Times, 20 February 2008]

Since the stir caused by his invigorating recordings of Mozart’s operas there has been a keen following whenever René Jacobs appears in the opera house. For these performances of Handel’s Giulio Cesare, shared between Brussels and Amsterdam, he has brought the Freiburg Baroque Orchestra with him for a few weeks in the frosty north.

Houston Grand Opera: A Life of Many Acts

By Patrick Summers [Playbill, 20 February 2008]

By Patrick Summers [Playbill, 20 February 2008]

Verdi, Wagner, Massenet, and Puccini wrote only opera, though they each made brief forays into other forms--I classify Verdi's monumental Requiem as his finest work. The focus of Handel's and Bach's lives was vocal music. Mozart, the exception to every rule, was creatively inspired by every musical genre and master of all of them, though he seemed to hold the most affection for stage works.

José Carreras

Alfred Hickling [The Guardian, 20 February 2008]

Alfred Hickling [The Guardian, 20 February 2008]

Domingo brought drama and dynamism, Pavarotti had the most exquisitely poetic tone, while Carreras ... Actually, it was never completely clear what Carreras brought to the Three Tenors party, except poignancy perhaps; his voice having endured the twin traumas of leukaemia and Herbert von Karajan who, in pushing Carreras's delicate instrument towards the heavyweight end of the tenor spectrum, may have hastened the deterioration of vocals once likened to a silken thread into a timbre more reminiscent of a fraying rope.

L.A. Opera unearths music suppressed by the Nazis

By TIMOTHY MANGAN [The Orange County Register, 18 February 2008]

By TIMOTHY MANGAN [The Orange County Register, 18 February 2008]

A listener has a rooting interest in Los Angeles Opera's "Recovered Voices" project. The annual series revives music suppressed by the Nazis, much of it, but not all, by Jewish composers, some of it by composers who died in concentration camps. If the Nazis hated it, it must be good, so the thinking goes.

Anna Christy Triumphs in Lucia di Lammermoor at ENO

Dramatically, Lucia di Lammermoor is perhaps the composer’s finest work, and one of the most obvious precursors to Verdi, but it’s also one of the most problematic to cast, not least because of its daunting historical association with some of the greatest sopranos and tenors of the twentieth century.

If any opera company can be relied upon to make a credible ensemble piece of an opera that’s known for being a star vehicle, it’s ENO, and this first new production of 2008 is a triumph. It may not be orchestrally thrilling — Paul Daniel’s conducting doesn’t really allow any rhythmic variation or space, at least for the first two acts — but the staging is dramatic, emotionally involving and coherent, and the principal casting is almost faultless. All did not go entirely to plan on opening night; singing the chaplain Raimondo, Clive Bayley succumbed to a chest infection part-way through the first act and he continued to mime the role to the voice of his cover, Paul Whelan, who is due to sing two scheduled performances of his own at the end of the run, but who on this occasion sang from one side of the proscenium.

In David Alden’s bleakly monochromatic production, with sets by Charles Edwards and costumes by Brigitte Reiffenstuel, emotion takes second place to practical and political considerations. A fixation with the past — particularly childhood, and images of dead ancestors — prevents anybody from influencing their own future or bringing anything interesting or new into their lives. It has turned Enrico into a bitter, almost emotionless shell, with a perverse obsession with his naïve young sister, whom he keeps trapped in childhood before brutally ’breaking her in’ and throwing her into her unwanted marriage to Dwayne Jones’s soulless pretty-boy Arturo. Mark Stone’s sense of bel canto legato leaves something to be desired, but the darkness in his voice makes his Enrico deeply nasty.

Edgardo is really no better. While Enrico’s reaction to his surroundings and the events of his past have turned him introverted and cruel, Edgardo has become careless, rash and impetuous, which ultimately makes him almost as responsible for Lucia’s fate as her brother. Barry Banks’s vocal and dramatic power belie his small stature; his presence is easily a match for Stone’s, and his final aria sequence is thrillingly, beautifully sung.

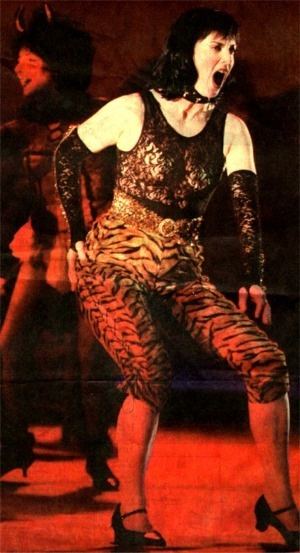

The Mad Scene (Anna Christy in foreground)

The Mad Scene (Anna Christy in foreground)

In the tile role, Anna Christy’s remarkable physical portrayal and crystalline soprano — not audibly marred by the bronchitis which had prevented her from completing the dress rehearsal — make her utterly convincing as this troubled, abused young girl. There is something other-worldly about her voice, and its partnership with the glass harmonica (restored to the Mad Scene as Donizetti intended) creates a chilling resonance. Although the libretto refers to her passionate nature, passion is lacking; she is more of a dreamer. We first see her perched at one side of a miniature stage, gazing obliquely at the closed curtain; she is discovered there again following Raimondo’s revelation that she has murdered Arturo, and during the mad scene, after the curtain is pulled back to reveal her husband’s bloodied body, she gradually retreats into the “stage” area as if it is the realisation of a long-held dream.

Tellingly, the blood which drenches Lucia’s and Arturo’s wedding-night garb is almost the first colour that’s been onstage all evening; it serves as both a coup de theatre and a symbol of Lucia’s release through madness from the bonds of her dead, grey, repressed surroundings.

Ruth Elleson © 2008

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Christy_Lucia_medium.jpg image_description=Anna Christy in Lucia di Lammermoor (ENO) product=yes product_title=Gaetano Donizetti: Lucia di LammermoorEnglish National Opera, 19 February 2008 product_by=Above: Anna Christy

Der fliegende Holländer, Stuttgart Staatsoper

By Shirley Apthorp [Financial Times, 13 February 2008]

By Shirley Apthorp [Financial Times, 13 February 2008]

This corporate jaunt has gone horribly wrong. Middle managers strew the contents of files like confetti, their wives huddle on the ground and smear their faces with dirt, champagne is sprayed across the crowd while dancing girls jerk neurotically in the far corner.

Susan Graham; Wigmore Hall

Hilary Finch [TimesOnline, 13 February 2008]

Hilary Finch [TimesOnline, 13 February 2008]

There's always something fishy about the French. Noël Coward noted it, and Susan Graham sang it, as the perfect encore after an evening of unashamed Francophile indulgence. A London recital by the great American mezzo-soprano is rare. The house was full and expectations were high. And Graham, with her accompanist Malcolm Martineau, offered us 24 songs - and 22 composers. It was an evening of canapés and bonnes bouches, with not a single main course in sight.

February 19, 2008

CHERUBINI: Medea

Music composed by Luigi Cherubini. Libretto by Franoçois-Benoît Hoffman. Italian version by Carlo Zangarini.

First Performance: 13 March 1797, Théâtre Feydeau, Paris.

| Principal Characters: | |

| Jason [Giasone], leader of the Argonauts | Tenor |

| Medea [Médée], his wife | Soprano |

| Neris [Néris], her confidante | Mezzo-Soprano |

| Creon [Créon, Creonte], King of Corinth | Bass |

| Dirce [Dircé, Glauce], his daughter | Soprano |

| First attendant | Soprano |

| Second attendant | Mezzo-Soprano |

Setting: The palace of Creon.

Synopsis:

Act I

The wedding of Jason and Dircé, daughter of Creonte, is approaching. In a gallery in Creonte's royal palace the bride-to-be is tormented by anxiety fearing the possible return of the sorceress Medea, who refuses to accept that Jason, to whom she has given two children, has abandoned her. The chorus and the confidantes of Dircé attempt to comfort her, as do both Jason and Creonte.

The sudden appearance of Medea comes as a terrible shock to Dircé and Jason has to lead the sorceress away. Medea tries to bend to Jason's will, hoping to dissuade him from his decision to be married again. But the contrast between the two leads to the bitter hatred of Medea who summons Colchos and his darkest horrors to prevent the wedding taking place and to avenge Jason's refusal to hear her pleas.

Act II

In a wing of the palace near the temple of Juno, Medea, the abandoned and furious wife, calls upon the terrible Eumenides to shed blood and bring terror to Creonte and his daughter Dircé. Accompanied by her hand-maiden Neris, Medea obtains Creonte's permission to spend one more day in Corinth. The king begs her to calm her wrath, whereas she, with the help of Neris, is seeking vengeance to match the offence and suffering she has known.

Medea's next encounter with Jason sees her in remissive attitude, as she asks her former husband to let her have her two children back. So upset is she that she is prepared to try to win the pity of Jason, but Jason will not be moved. Medea is hurt and insulted. Events confirm her desire to seek the vengeance that she had planned. She confides in Neris, telling her that she intends to give the bride-to-be Dircé her gown, crown and her personal effects all poisoned. During the wedding procession Medea pronounces cruel wishes for the couple.

Act III

A storm which obscures the scene is the idea backdrop to the appearance of Medea who steps forward dressed in a black veil. She is awaiting the children of her marriage with Jason to complete her criminal plans. Neris pushes the children into their mother's arms. Medea is touched when she sees them but will not be distracted from her plan to kill them. They are her children but what matters most is that Jason is their father and through the children he must pay for the offence he has committed.

Cries from the palace inform us that Dircé is dead. Jason, moved to pity and fearful for his children, begs Medea to bring them to him: it is too late, they have already been killed. Jason is crushed by his sorrow. Medea calls to him that she will be waiting for him on the banks of the Styx and then sets fire to the temple.

As the crowd runs from the blaze, the flames spread and engulf both the temple and the palace; thunderbolts heighten the terror; the mountain and the temple collapse. The destruction and flames destroy the scene. Medea disappears among the burning remains.

[Synopsis Source: Opera Italiana]

Click here for the complete libretto.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Callas_portrait.png image_description=Maria Callas audio=yes first_audio_name=Luigi Cherubini: MedeaWinAMP, VLC, FooBar first_audio_link=http://www.operatoday.com/Medea1.m3u product=yes product_title=Luigi Cherubini: Medea product_by=Medea: Maria Callas

Giasone: Carlos Guichandut

Neris: Fedora Barbieri

Glauce: Gabriella Tucci

Creonte: Mario Petri

Capo delle guardie: Mario Frosini

Prima ancella: Liliana Poli

Seconda ancella: Maria Andreassi

Orchestra e Coro del Maggio Musicale Fiorentino

Vittorio Gui, Direttore

Andrea Morosini, Maestro del coro

Live Performance, 7 May 1953, Florence

SALIERI: Prima la musica e poi le parole

He wanted these pieces to entertain his guests at a party for the visiting Prince Albert of Sachsen-Teschen and his wife, Marie Christine (Joseph’s sister). From stages set up at opposite ends of the Orangerie at Schönbrunn, the Italian troupe performed Salieri’s Prima la musica e poi le parole, and the German troupe put on Mozart’s Der Schauspieldirektor. The evening highlighted Joseph’s love of competition in music: between composers, librettists, singers, and languages. Both these pieces represent what Betzwieser calls “metamelodramma,” that is, an opera in which the subject of the plot is opera itself. (I prefer John Rice’s term “self-parody.”) This is not a new category of theater, and these are not the last examples. Benedetto Marcello poked fun at operatic excesses in his satirical tract Teatro alla moda (1720). From the eighteenth century there are several parody operas: Domenico Scarlatti’s La Dirindina (1715), Domenico Sarri’s L’impresario delle isole Canarie (1724), and F. L. Gaβmann’s Opera Seria (Calzabigi’s libretto La critica teatrale), 1769; more recently, one thinks of Richard Strauss’s Capriccio (1942), which was inspired by the Salieri work, and even the likes of “Chorus Line” and other Broadway musicals. Moreover, the debate over which should have primacy, words or music, goes further back into the history of music: Monteverdi clashed with Artusi over the “prima prattica” and “seconda prattica,” and Gluck endeavored to reform opera seria.

Salieri’s one-act divertimento teatrale has a cast of four characters, each depicting a player in the creation of an opera: the Maestro (bass), the Poet (bass), Eleonora (soprano), a prima donna, representing opera seria, and Tonina (soprano), an opera buffa singer. The plot lampoons everyone and everything in opera production. The Poet is obliged to write his verses to music already composed by the Maestro, who cares nothing about expressing the words in the music. Both singers try to use unfair influence. Seria and buffa elements (normally kept strictly apart) collide in a duet of two simultaneous arias, in which Eleonora sings hers in the serious style and Tonina sings hers in the comic style. And so on.

Salieri was fortunate to collaborate with the skilled librettist, Giovanni Battista Casti, whose dramaturgy easily surpasses that of Mozart’s librettist, Johann Gottlieb Stephanie. The editor observes: “Casti’s and Salieri’s opera is incomparably richer in allusion than its German counterpart.” This very genius, however, contained the seeds of its own destruction. What was readily apparent to 18th-century Viennese audiences, but unlikely to be perceived by today’s listeners are the musical references to and quotations from popular operas of the time. Opera fans will recognize this technique from the supper scene in Mozart’s Don Giovanni, where the composer quotes from operas by Martin, Sarti, and his own Figaro. In Prima la musica, Salieri borrowed much more extensively. The editor cites three long “complexes of quotations” from Giuseppe Sarti’s Giulio Sabino, including a castrato aria transferred here to female soprano. Thus, laden with allusions to the Viennese operatic world and bearing myriad quotations, Salieri’s opera was not “viable” beyond the imperial city, where it received only three more performances. This fate sets it apart from his many operas that achieved wide-spread popularity, and made him one of the most celebrated composers in Europe.

Despite its short run, Prima la musica represents Salieri at the height of his musical and dramatic creativity. The score masterfully entwines the serious and comic, taking many colorful twists and turns. The action entertains by farce, absurdity, even slapstick. On the whole, it stands up well against the inevitable comparison with the Mozart companion piece. (May I suggest that to solve the problem of unrecognizable quotations we should revive Sarti’s Giulio Sabino.)

Prima la musica was published in a vocal score by Schott in 1972, and it has been revived in performance a number of times since then. Nikolaus Harnoncourt directed a production in Vienna in 2005. The present publication is the first “Urtext” and critical edition. The vocal score, extracted from the critical edition, has the text in Italian with a good singing German translation. The full score and orchestral parts are available as rental. According to the preface to the vocal score, Betzwieser examined all the surviving sources (the composer’s autograph score and three manuscript copies), and it seems evident from the vocal score that the edition has been carefully prepared. This publication of Salieri’s Prima la musica e poi le parole is a welcome addition to the growing corpus of Salieri’s works available in good critical editions.

Jane Schatkin Hettrick

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Salieri_Prima.gif image_description=Antonio Salieri, Prima la musica e poi le parole product=yes product_title=Antonio Salieri, Prima la musica e poi le parole product_by=Edited by Thomas Betzwieser, vocal score prepared by Karl-Heinz Müller (Kassel: Bärenreiter-Verlag, 2007) product_id=ISBN/ISMN M-006-52155-5BA7698 90 price=€29.95 product_url=https://www.baerenreiter.com/cgi-bin/baer_V5_my?kat=/baerenreiter/baer&mark=M-006-52155-5&uid=595614X1273904146&ln=en&wrap=artikel1.htm&ac=mark2refnr&kz_wgrp=M-006-52155-5&searchdef0=%26%20BOOLEAN_SEARCH%20PATTERN_ALL%20WORD_SCORE%2880%29%20SYNONYM&begriff0=prima%20la%20musica&kategorie0=$art_english.inhaltsangaben%2ceditionsnummer%2ckomponist_autor%2cbeschreibung1%2ckurzbez&searchdef0=%26%20BOOLEAN_SEARCH%20PATTERN_ALL%20WORD_SCORE%2880%29%20SYNONYM&kategorie1=komponist_autor&kategorie2=besetzung&begriff3=X&kategorie3=kz_anz&searchdef3=exactmatches&kategorie4=besetzung&kategorie5=besetzung&kategorie6=besetzung&kategorie7=editionsnummer&searchdef7=multiple&verknuepfung=AND&orderdef=komponist_autor%2c%20editionsnummer&count=108&return=15&kat=%2f%2fbaerenreiter&user_priv=guest&total=15&start=90

February 18, 2008

Jonas Kaufmann—Romantic Arias

This young German singer is making a fine reputation for himself in European opera houses. He has appeared at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York most recently as Alfredo in La Traviata, which he is scheduled to reprise in March of this year.

So this is an eagerly awaited album on both sides of the pond. And the wait was worth it.

There are 13 tracks on the disc that represent a variety of styles. The standards are there, “Che gelida manina” from La Boheme, “La Fleur que tu m’avais jetee” from Carmen, and “E Lucevan le stelle” from Tosca. These are well sung and totally fit the title of the album in evoking the romantic feelings that their composers intended.

This tenor is building a reputation on a broader scale than those familiar arias would indicate. Some of the composers on this disc range from Flotow, to Verdi, to Wagner and include Berlioz and Gounod and Massenet. Kaufmann is a versatile singer who, here, demonstrates where his skills and talent may take him in the future. He has sung Parsifal and Florestan (Fidelio) on stage, which is even more testimony to his versatility.

The Prize Song from Die Meistersinger is beautifully rendered, and I hope it might be a precursor to his singing that role down the road.

Each of the selections on the album requires a different degree of passion and Kaufmann gives us that. The gentle song of love to Mimi in La Boheme that rings with his new found passion for her is contrasted with the beautiful “Pourquoi mr revellier” from Werther, an aria of unfulfilled love and passion and the precursor to Werther’s death. Kaufmann clearly understands the different passionate needs of the arias and fulfills those emotions..

I was particular impressed with his attention to the words and his diction in the three languages sung on this album. I want a singer to sing the words and not slur them so they are unrecognizable as language. Kaufmann is as clear in his native German as in he French and Italian.

There is a rich, dark and intriguing quality to Kaufmann’s voice. His commitment to the works he is singing is readily apparent. I suspect that over time the darker tenor roles such as Cavaradossi and Don Carlo will be more his style than the lighter Alfredo. I found his delivery effortless and his demeanor very romantic indeed!

Missing from this debut effort is anything by Mozart. Kaufmann includes many of the composer’s work in his repertoire. One would hope that the lack of any Mozart on this disc might be a precursor to a disc of Mozart or German composers in the future. So if anyone at Decca is listening………..

This is a tenor for the 21st Century who has a fresh sound and some fresh ideas and will grace our opera houses for a long time. His good looks as well as his beautiful voice will continue to give rise to the romantic leading man image that this album is all about.

Cheryl Dowden

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Kaufmann.png image_description=Jonas Kaufmann—Romantic Arias product=yes product_title-Jonas Kaufmann—Romantic Arias product_by=Jonas Kaufmann (tenor), Prague Philharmonic Orchestra, Marco Armiliato (cond.) product_id=Decca 475 9966 [CD] price=$15.99 product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/album.jsp?album_id=185095February 17, 2008

ENO's The Mikado

It is a sure-fire winner – a good-looking, funny, energetic show with appeal for all the family.

Its central premise is that the Japanese setting for Gilbert and Sullivan's best-known work is purely incidental, and the operetta is very much a satire on English society and values. Although we remain ostensibly in Japan, the set is clearly a smart English hotel circa 1930, and the male chorus represent various caricatures of the English upper classes of the time. The accents are cut-glass; the costumes and sets are immaculate in cream, and every character from monarch to maid is flawlessly turned out. Even the patches on Nanki-Poo's artistically ragged trousers are perfectly finished.

Ko-ko's “little list” is rewritten for 2008 with moderate success; a few very funny lines about politicians and footballers were balanced out by many more obscure topical references. And after all these years, Richard Suart is inseparable from the role, with a talent for finding a funny side in lines which are normally played straight ('I dare not hope for your love – but I will not live without it' as Ko-ko tries to persuade Katisha to marry him in order to release him from his imminent execution). He frequently overacts to the point of being unfunny, but I suspect that the desperation to please is – at least to some extent – part of the act.

Other experienced members of the cast include Graeme Danby as a softly-spoken Pooh-Bah, Richard Angas's genial Mikado in a costume which seems almost as wide as he is tall (and he IS tall) and Frances McCafferty's Katisha, dominating every scene with a well-balanced tragicomic portrayal and an expert sense of musical phrasing which alleviates the disadvantages of an ageing voice.

Leading the younger contingent, Sarah Tynan's Yum-Yum is a fresh-voiced and fresh-faced delight. And she's well balanced by Robert Murray, a newcomer to the production as Nanki-Poo. It's good to see that such talented singers as these are successfully managing to forge careers on both sides of the inexplicable divide which historically seems to have separated 'Gilbert and Sullivan' from 'opera'. Both singers are becoming familiar faces in ENO's G&S productions, yet they are among the most versatile young opera soloists on the scene at the moment.

The conductor is Wyn Davies, who tends to take things rather slowly – perhaps this is why the tap-dancing maids and other choreographic highlights weren't quite as polished as I remember them being. However, the hilarious male corps-de-ballet of headless bodies has to be seen to be believed!

Ruth Elleson © 2008

image=http://www.operatoday.com/mikado268.png

image_description=Sarah Tynan (Yum-Yum) and Robert Murray (Nanki-Poo) [Photo © Alastair Muir and ENO]

product=yes

product_title=Gilbert and Sullivan: The Mikado

English National Opera

product_by=Above: Sarah Tynan (Yum-Yum) and Robert Murray (Nanki-Poo)

Photo © Alastair Muir and ENO

LA Opera: Tristan und Isolde

Although on face value the piece might serve as a cautionary tale against sharing any adult beverages with your love interest du jour, the LA production persuasively plumbed the work’s musical depths and romantic sentiments, and made a loving Valentine indeed out of the mystic beauty contained in Wagner’s finest Gesamtkunstwerk.

David Hockney’s evocative scene design is being seen in its second revival, having premiered in LA in 1987. It remains quite a handsome and effective production, well-maintained, and beautifully lit by Duane Schuler. Indeed, the deceptively monochromatic look of many structural surfaces takes the light exceptionally well, and the transformative powers of different strong color filters created masterful delineation of the story’s quicksilver moods. The judicious use of specials, area lighting and tight follow spots heightened the shifting destinies of the principal characters.

A modern-art re-imagining of the structural elements of Act One’s ship included a colorful, broadly striped raked deck receding with forced perspective; wildly stylized sails and colorful draperies, akimbo in the wind; and a chaise for “Isolde” that would not be out of place in a Picasso cubist drawing. Act Two’s fateful garden featured a similar rake, with a grove of trees receding at stage left, topped with cut-out boughs right out of a Matisse scrapbook; and a rather more realistic fortress wall running the length of stage right, the balcony of which looked to be “Juliet’s” famous perch, borrowed from Verona.

The serene field in Act Three is arguably the the most fanciful structure, rising on the upstage rake to include a sort of shapely “splashing wave” of green meadow. A couple of well-placed field stones are framed by a large cutout tree branch just behind the proscenium. All of this set was quite colorless at first, commenting on “Tristan’s” coma, then catching fire in the colored lights to great effect as his agitation mounts.

John Treleaven (Tristan)

John Treleaven (Tristan)

While all of this worked well enough, it has to be said that Mr. Hockney’s highly individual decorative gifts did seem to root the visuals in an artistic vocabulary of, well, twenty years ago. And, for all the imagination that the set and lights embodied, the costumes were merely (though not badly) Prince Valiant Standard Issue, albeit in faaaaaaaaaabulous colors. Our heroine looked especially lovely in her deep wine gown --- well, okay, okay, with the sole misjudgment of plopping a squatty crown with clinging veil on her head to meet “King Marke,” which had the dire effect of reducing her visually, however briefly, to a pissed off Smurf.

Music Director James Conlon brought his considerable experience to bear and led a richly detailed, rhythmically propelling, dramatically taut, and downright lavish reading of this glorious score. To name but one superb moment in an afternoon of abundant delights, the aching and longing of the Act Three prelude has seldom been so deeply felt and profoundly affecting. From those first familiar arching phrases and restless chords, he was in full command of his forces, and shaped the proceedings with passion and intelligence.

Linda Watson (Isolde)

Linda Watson (Isolde)

Balance with the stage was sometimes another matter, but only sometimes, and then only when the principals were singing rapid declamation in their lower registers. One such time was in “Brangaene’s” important exposition where the beautiful cello solo, meant to be commenting, was instead competing.

It must said that the Dorothy Chandler is a notoriously patchy house for acoustics, and that Wagner himself was not always careful in balancing the voice with the large band. Still, with that apologia comes the avoidable reality that the poorly amplified chorus throughout Act I sounded as though they were singing in the subterranean men’s room. Still, if I have heard this luminous piece better-served instrumentally, I can’t recall when it was.

Of course, the supremely difficult vocal challenges of the title roles can either be legend builders or more often, voice shredders. In any generation we count ourselves lucky to find one duo that can encompass these multi-layered demands. Happily, in LA, the ol’ Helden-Meter tilted decisively to the success side with the committed portrayals and well-paced assumptions by the experienced stage “lovers” of John Treleaven and Linda Watson.

The tenor really has a tougher time of it than the soprano, going from the lengthy ecstatic outpourings of the Love Duet, right into the even lengthier steady crescendo of Act Three’s delirious lament. Mr. Treleaven brought an assured vocal presence, handsome enough demeanor, and tragic bearing to his assignment. If he does not have Ben’s burnished tone, well, small matter, as his rather bright sound was pleasant to listen to, and he could muster enough heft for credible, audible dramatic statements. Not surprisingly, a bit of fatigue crept into his extended death scene, but nonetheless he husbanded his gifts and scored all the major points.

I first heard Linda Watson as DC’s “Bruennhilde” in “Die Walkuere” and my impressions were largely confirmed here. Her “Isolde” was strongly and musically sung with a warm voice of considerable amplitude, marked by a generous vibrato that imbues each phrase with a very womanly presence. She is a major league player in the Isolde Sweepstakes, and her “Liebestod” was memorably delivered.

I did wish that she would not seek to pulverize certain climactic high notes but rather just allow them to ring full out. The extra energy she occasionally invests in these disparate top notes sends them fraying a little, and finds them losing the focused core of the pitch. Too, in the complicated and heated overlapping exchanges of the love duet, the tone at top went a little strident at full tilt. Still, she is understandably numbered among today’s very top interpreters of the Irish Princess, and the audience was unreserved in their appreciation of her outstanding efforts.

Lioba Braun is a singer with a lovely sound, beautiful stage presence, and wonderful musical gifts, but while I really like a little more bite in the tone for “Brangaene,” her “Watch” was exquisitely sung, and a highpoint of her portrayal. Juha Uusitalo offered a rather lackluster account of “Kurwenal” in the first two acts; so much so, that I was unprepared for the searing vocalism he brought to bear in his great scene in Act Three. Suddenly I felt I wanted to hear this artist again in a larger assignment.

Veteran bass Eric Halfvarson brought all of his stage savvy and colossal voice to the small role of “King Marke,” hitting every money moment squarely on target. Gregory Warren was doubled as sweet-voiced “Young Sailor” and “Shepherd.” In his few well-sung phrases as “Melot,” Brian Mulligan displayed a gorgeous baritone and well-schooled (if not quite idiomatic) German.

What to say about Thor Steingraber’s stage direction? Generally speaking, I found the blocking efficient at best, indifferent at worst. The love duet especially is a hard nut to crack. I mean, with the orchestra in full “Geschrei” the two lovers/soloists just simply have to — have to — sing front. And so they did, but in wholly unimaginative placement and movement. There was nothing terribly “wrong” with it. Just nothing “interesting” about it either.

There were compensations: “Brangaene’s” indecision, and subsequent serving up of the love potion was as clearly staged as I have ever seen it, and the end of the “Liebestod” was inspired. Instead of “Isolde” drooping on poor “Tristan” or just fading away, or just standing there (sorry Richard, neither the text nor the music really help much in explicitly defining her as dying of love), here our hero rose from the dead to join the heroine in the icy blue lighting special, put his hands over hers which she had extended in ecstasy, and then enfolded both of them in his loving final embrace. It was a great solution, and one I can recommend to other producers.

Cupid’s arrow may or may not not find its mark this Valentine’s Day, but luckily for me at least, LA Opera’s traversal of “Tristan und Isolde” has almost totally fulfilled my seasonal romantic longings.

James Sohre

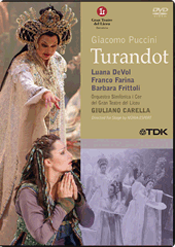

image=http://www.operatoday.com/James_Conlon.png image_description=James Conlon product=yes product_title=Richard Wagner: Tristan und IsoldeLos Angeles Opera product_by=Above: James Conlon

Rodelinda at Portland

In the title role, the radiant Jennifer Aylmer showed off quite a full arsenal of technical perfection. Throughout the night Ms. Aylmer not only poured out plangent legato phrases, trip-hammer fioritura, and unfailingly lovely tone at all volumes and in all registers, but also displayed a solid technique, handsome stage presence, and an admirable command of this difficult genre. If her trills were sometimes approximated it was small matter. Hers is a major musical presence on the current scene and happily for us all, these days she is singing all over the map.

That said, for all her strengths, at the top of the show I thought she lacked the weight of voice, or perhaps the seriousness of dramatic purpose required. “Rodelinda” begins in tragedy mode, which accelerates rapidly to righteous anger. I certainly thought the voice a wonderful instrument from the git-go, but perhaps a half-size too small. Her first splashy coloratura harangue, while clean and musical, seemed more “petulant soubrette” than “royalty wronged.”

Indeed throughout Act One, I was thinking rather what a memorable “Susanna” she would be, and then, lo, from Act Two onward, as her performance deepened I settled into a broader appreciation of her talents for the work at hand. Maybe she was pacing herself? Or maybe I just got over myself! In any case, while she is not “quite” just yet Beverly or Renee or Cecilia in this repertoire, this is a major talent with a great future. Watch for her.

Arguably, the “discovery” of this production was countertenor Gerald Thompson as “Unulfo.” We have come a long way since pleasant rarities like Russell Oberlin, let me tell you! Mr. Thompson has an uncommonly impressive instrument for this Fach, full-bodied, expressive, responsive, capable of every demand that Handel asks of it. Our singer absolutely and thrillingly nailed every sixteenth note of the (extremely) rapid passage work with fiery precision. Moreover, he displayed real heart in his slower parlando passages. So accomplished was he, that I found myself wishing that he were the one singing the incomparably lovely “Dove Sei,” one of leading man “Bertarido’s” big set pieces. (He has sung the role elsewhere.)

Not that Jennifer Hines didn’t bring many fine qualities to her impersonation of our hero. She is a handsome woman with good musical instincts and a well-schooled mezzo. While her dark, almost vibrato-less sound should have been well-suited to this male character, her production did not seem grounded in the speaking voice, at times sounding hollow instead of troubled, backward-placed instead of forthcoming. She had all the notes for her final showpiece aria, but scarce brilliance of tone. Perhaps I have become too accustomed to the luxurious bravura of Horne or Verrett or Larmore in such trouser roles, but Ms. Hines seemed mis-cast, not in agility or intelligence or intentions, but in vocal star presence.

The “Eduige” of Emma Curtis had plenty of spunk, and she quite successfully married her rock solid low register to a rather rich middle and a secure, if slightly thinner top. She managed some awesome arpeggiated licks with thundering baritonal low notes, but her generous vibrato caused a little grief in slower passages in the lower middle voice, when the “point” of the pitch got muddied a bit here and there.

For the first two acts, it was difficult to make out the skill set of tenor Robert Breault’s “Grimoaldo.” His florid singing seemed accurate enough, if somewhat thin and scaled back, and I had the feeling he wanted to lag behind the beat. Then, suddenly, ringing climactic high notes would appear that rattled the chandeliers. Hmmmmmm. Looking at his credits, this is a guy who sings “Cavaradossi” and “Don Jose” and here he was, frogging around in melismatic Handel, for God’s sake. Then in Act Three, Mr. Breault was totally vindicated with a memorable and moving reading of his big scena of doubt and redemption. Amazingly fine.

In the mute role of “Flavio,” young lad Jamesmichael (sic) Sherman-Lewis (don’t you love that name?) was adorably effective without upstaging. Bass Verlian Ruminski was so terrific as “Garibaldo” that I dearly wished the role were not so small. He tore up the stage with his solidly projected arias and theatrical conviction.

And “theatrical conviction” is a point of discussion in considering Helena Binder’s staging. It is interesting that in other times and places, producers have occasionally sought (with considerable effort and imagination) to make viable stage pieces out of oratorios. But here it seemed that we were looking at a highly stage worthy opera, which was reduced on more than one occasion to an oratorio.

Let me first say that Ms. Binder’s management of the logistics of exits and entrances, integration of set changes, and creation of lovely tableaux was skillfully done. And she is mistress of focusing the attention in all the right places, striving to serve the story well. Believe you me, these are no small skills, and we could use more directors/producers with this mind set.

However, to my taste there were too many instances of “stand-and-sing” or busy movement that did not illuminate the relationships, nor develop the character. You know, those interludes of stage “busy-ness.” You’ve seen it: “Now I will walk right; nope, nope; I will stop as if remembering I really wanted to go left; maybe; maaaaybe; nope, left’s not it; I’ll just stop; and. . .oops-it’s-time-to-sing-again.”

Too, a pattern emerged of having the soloists tromp off stage at the end of almost each and every aria, sometimes way too soon prompting applause over the postludes, and leaving silence in the ensuing set changes which could have been better covered by the audience reaction to the aria. I appreciate the artistic decisions that were made and the consistency of their execution, all the while I would yet urge Madame Director to further develop the character relationships, delve into more specificity, and take fuller advantage of the ripe dramatic possibilities.

John Copley’s pleasing settings were an effective modern interpretation of Baroque theatrical conventions, like the “in-one” scene changes. The playing space was made more intimate by a succession of receding square proscenium-like frames which threw the action forward to the primary playing space on a red lacquer square front and center stage.

Within this simple and elegant black and white unit, minimal furniture and key set pieces (like “Bertarido’s” memorial) were smoothly placed and removed by costumed servants. The colorless silhouettes of scenery flown in and out behind the upstage frame suggested trees, prison, gravestones, etc. like stylized and unadorned paper cut-outs. The shallow apron area had the advantage of bringing the singers forward more often than not, but had the disadvantage of somewhat restricting blocking to more linear moves.

The beautiful lighting design by Thomas J. Munn achieved lovely effects, especially with back lighting and isolated areas. The uncredited lavish costumes (Mr. Copley?) appeared to have been updated to Handel’s time, and well, why not? They enhanced the character, and looked gorgeous to boot.

Musical matters were in secure hands with conductor George Manahan. While modern instruments were used, there was the usual inclusion of the (winningly played) theorbo and baroque guitar. There are trade offs in this choice. While the ensemble was immeasurably better tuned that some “early music” bands I have heard (ooh, was that my out-loud voice?) it also lacked the special color that great “original instrument” players can elicit. Playing with minimal vibrato and well-considered style, purists be damned, the Portland pit contributed some beautiful, idiomatic support.

Ever felt like a jaded opera fan who has maybe “seen it all”? I sure did as I watched lines of patrons parade to the orchestra pit at both intermissions to see just what this “theorbo thing” was all about. Many had never seen one before, and it was a total delight to be party to their discovery. Too, it should be remarked that there were any number of young people in attendance. The Goth Valentine’s couple in the row just behind me seemed to be getting off on “Rodelinda” with an uncalculated enthusiasm often lacking at such temples as Glyndebourne or Glimmerglass. Other companies with a maturing customer base might do well to study what Portland is doing right in audience development.

If I heard more “woo-woo-woo’s” than “bravi” at the curtain call, the net result was the same. The Portland public seems to know and appreciate the fact that they have a top notch producing organization, whose high standards were always in evidence with this enjoyable “Rodelinda.”

James Sohre

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Aylmer_Jennifer.png image_description=Jennifer Aylmer product=yes product_title=G. F. Handel: RodelindaPortland Opera product_by=Above: Jennifer Aylmer

Navajo oratorio a triumph in Phoenix

No! — at least not when the designer in question is Mark Grey, who is now emerging as a major American composer. Listen to Grey’s new “Enemy Slayer” and you’ll hear what the difference between a designer and an engineer is. The beneficiary of extensive collaborations with John Adams, Peter Sellars and the Kronos String Quartet and of work at a Norwegian jazz club above the Arctic Circle, Grey understands sound — the raw material of music — as a fashion designer understands fabric, color, cut and style.

“I sit in the audience surrounded by people’s reaction to music,” says Grey, now 41. “I feel their emotional energy and I know how to sustain a tension that keeps them involved.” In “Enemy Slayer” Grey has woven a sonic tapestry that overwhelmed the audience at the premiere of the work by the Phoenix Symphony on February 7.

Commissioned by the orchestra to mark its 60th anniversary, the 70-minute oratorio is something new in music. One does not seek to define the style of the score, but surrenders rather to a flow of energy that parallels the forces of nature. True, Grey employs bi-tonal and bi-diatonic means to make the score increasingly atonal as the story develops, but these are only the externals of an achievement that has all the markings of a Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk [italics] — a composite work of art that might well prove a major monument of early 21st- century music. And the contemporary relevance of “Slayer,” subtitled “A Navajo Oratorio,” will astonish those who come to the work “cold,” expecting an evocation of the Native-American past but confronted by a wrenching drama of the present day.

A young Arizona native returns to his people from a desert war, where a cousin died in his arms. "Your blood poured brightly through my hands like a lamb being slaughtered,” sings the baritone soloist. “I could not stop it!"

In the story, told in verse with urgency and economy by Laura Tohe, a Navajo poet on the faculty of Arizona State University, the monsters of native myth become the tormenting memories of death and devastation that haunt the returned soldier and prompt him to tell his story. Although Grey’s ideas for the oratorio reach back several years, the work — once defined — was quickly written. Grey met Michael Christie, now in his third year as music director of the Phoenix Symphony, in 2004 in Rotterdam, where both were involved in the staging of John Adams’ “Death of Klinghofer.”

“Several times we took the train to Amsterdam to hear the Concertgebouw and visit museums,” Grey says. “The trip was an hour each way, and that gave us time to swap ideas.” Christie premiered Grey’s violin concerto “Elevation” at the (Boulder) Colorado Music Festival in 2005 with Leila Josephowicz as soloist. The conductor had just accepted the Phoenix appointment and talked with Grey about a new score for the orchestra‘s up-coming anniversary. “Michael is eager to premiere new and exciting works,” Grey says. “And although he left the door open to me, the idea of an oratorio came up immediately.”

Grey thought about a re-telling of the David and Goliath story, but found that it had little meaning for Phoenix. At that point he stumbled on Monster Slayer and his brother, central figures in the Navajo epic of creation. Twin warriors, they made the world safe for others. Grey was especially fascinated by Nidaa', the Navajo ceremony that washes away the psychic torments resulting from violent acts. When Enemy Slayer returned from killing the monsters that had threatened his people, he went through this ceremony. The relevance to a modern veteran is obvious.

“We were not out to make this a literal translation of myth," Grey says, "but to view a ceremonial path through a contemporary lens.” Grey found librettist Laura Tohe by googling [does that need quotes?]“Navajo” and “poet.”

Mark Grey

Mark Grey

Born on the Arizona reservation and educated in one of its boarding schools, Tohe is now professor of English at Arizona State in near-by Tempe. And although Tohe admits that when she accepted the assignment as librettist she had to look up both “libretto” and “oratorio,” the idea of an updated version of native myth caught her fancy.

As Grey continued his research he saw this story increasingly within the context of the entire Southwest, for the Navajo reservation, the largest in the United States, reaches into New Mexico and Utah. “It’s a region rich in creation stories,” Grey says, “and more and more I felt the energy of this region with its mountain spirits, deities and monsters. “And it was clear to me that this would be a large work — a work for mammoth chorus and orchestra.”

Grey’s source material, of course, came from oral tradition, and that posed a problem. “The minute you write something down, you remove it from its ceremonial function,” he says. “And out of understanding for the Navajos and their community, we did not want to do that. “What we wanted was a contemporary window on a very old story.” And Grey opted for a single solo voice, a baritone protagonist as the suffering soldier and kept at his reading while Tohe moved the project forward. “Laura got me involved in a dialogue with the Navajo community,” Grey says. “She put together a group of elders, and with them we discussed cultural sensitivity — what was appropriate and what wasn’t. “She opened doors and built a bridge between us.”

Grey speaks of his collaboration with Tohe as “a shared passion.” “We achieved an incredible balance between Navajo tradition and a contemporary dialogue,” he says of the Strauss-Hofmannsthal relationship that characterized their collaboration from the beginning. “It was back and forth from the outset; we worked in tandem. I sent Laura fragments of the score, and she came by to talk with me. “Together we visited places associated with the story, and the cultural palette grew wider and wider.”

In one of their first conversations they agreed that there would be no effort to make the score “sound Indian.” Grey was determined to avoid the stereotypes that one encounters in films — and in contemporary operas. (Well-intended recent operatic exercises in cultural tourism come to mind: Henry Mallicone’s “Coyote Tales” (Kansas City, 1998). David Carlsons’ “Dreamkeepers” (Salt Lake, 1996; Tulsa, 1998, and Anthony Davis’ “Wakonda’s Dream” (Omaha, 2007). Grey felt no temptation to “import” drummers and dancers from the Navajo nation. “Their tales are told with dance,” he sys. “It is all part of a myth-rooted ceremony. You cannot take its components out of this context.”

The chorus — director Gregory Gentry expanded the PSO Chorus to 150 for the premiere — speaks for the Navajo people and in a larger sense for all humanity. “Family and community are especially important for the Navajos,” says Grey, noting that the chorus functions here much as it does in Greek tragedy. “The ensemble speaks with an ancestral voice; it is there to help — and to cleanse the returned soldier.” (Tohe tells of an older brother who never recovered from his involvement in the Vietnam War. Upon his return to Arizona he refused ceremonial cleansing and died at 40 from his exposure to the toxic environment of war.)

Given the power of Grey’s music and Tohe’s poetry the inclusion of a visual perspective on this story might seem superfluous. However, what photographer Deborah O’Grady contributes to this production is far removed from the travelogue sometimes considered a bonus at concerts. With what she defines as “projected visualizations” O’Grady has brought another dimension to the oratorio. Using the latest digital software, she underscores the sweep of the music with images that move and morph and make the Arizona landscape an integral part of the work. "I tried as much as I could to be sensitive to the music," O’Grady. “And with digital technology, you can do something more sophisticated than just one picture fading into another."

Most moving are O’Grady’s shots of the tattered flags above the Fort Defiance Navajo Veterans Cemetery. (O’Grady, by the way, is married to composer John Adams.) Soloist for the premiere was Scott Hendricks, a youthful American now in great demand in European opera houses.

“Enemy Slayer” is a big work — in the sense the Mahler is big. It requires space to tell a story of urgent importance that reaches across cultures and centuries, and at the premiere Christie demonstrated a refined understanding for the spaciousness of the score. The carefully prepared performance of Grey’s lush and loving music brought home just how original the composer is in his understanding of the design of music. He has created here a collage of colors that brings the many voices of soloist, choir and instruments together with near-magical homogeneity.

In “Enemy Slayer” Grey might well have composed cthe requiem that laments America’s unfortunate adventure in the Middle East. The work deserves to be widely performed. Michael Christie will conduct “Enemy Slayer” at the Colorado Music Festival in Boulder, Colorado, on July 24 and 25, 2008. Soloist at that time will be Daniel Belcher. For information, visit www.coloradomusicfest.org.

West Blomster

image=http://www.operatoday.com/desert-spire.png image_description=Desert Spire product=yes product_title=Enemy Slayer: A Navajo OratorioThe Phoenix Symphony

Tosca at COC

Instead, it would be the Canadian debut of ensemble studio soprano, Yannick-Muriel Noah. Many performers have gotten their “big break” by filling in for a sick colleague and in these situations; the somewhat indecisive role of the “understudy” suddenly becomes something magical. By having the opportunity to show their musical goods, huge international careers have been launched as a result of this very situation. And so, once the announcement was made, Puccini’s Tosca took on quite a different air: one of a fictional tale of real and passionate emotions juxtaposed with the non-fictional reality of a young opera singer making her debut as a fictional opera singer, Floria Tosca.

Puccini’s Tosca is often presented in one of two ways: it can be exciting and exhilarating, leaving one touched at one woman’s unwavering determination, or it can fall flat on its face should its diminutive cast be at all weak in their characterization. This production was a little of both. The one overall aspect that lacked focus was the common Puccinian dichotomy of Eros and Thanatos (Love and Death) which lies at the heart of this work. Cleverly, Puccini imbues the orchestral fabric with wonderfully suggestive moments that indicate this dichotomy, but if Tosca is to be successful, the characters must also inhabit each of these elements at a given point within the opera.

In Tosca, Puccini sews with the thread of religion, a topic that he was not so interested in, except for in his later Suor Angelica. In essence, the religious component in Angelica has nothing to do with religion at all, more than it uses the overall ideal of a religious setting to approach a story about a girl who got herself pregnant out of wedlock. It is a story of sin and redemption in the sense of a woman atoning for sexual urges. Atoning for love, passion, and sex by suffering and death is the concoction that Puccini continually fills into his syringe. With it, he pierces us and tries to teach us the more difficult lessons of living and loving. Tosca functions in an identical manner, however, this production failed to express these elements, for the most part. There were, however, several moments of excellent music making.

Conductor, Richard Buckley

Conductor, Richard Buckley

The first act began with an elegant sound in the orchestra and a well-chosen tempo by conductor Richard Buckley. He maintained a balanced orchestra fabric, if perhaps it was sometimes lacking in the larger and more dramatic moments where the orchestra is telling of the character’s innermost emotions. The Sacristan, played by Robert Pomakov, was directed in a rather incoherent way, for Puccinian aesthetics. The music of the Sacristan is light-hearted but his religious aura and pious nature are not to be affected. His piety was obscured by Pomakov’s almost spastic, buffo-like actions. Nowhere does Puccini indicate that the sacristan is a comical character. There is an indication in the score that the Sacristan has a “tic” in his neck, but this element of character was dramatically overdone and became somewhat ridiculous. Although Pomokov’s voice is quite lovely, the Italian was unacceptable for a house of this magnitude. There were aspirations of all sorts, where the authentic Italian language does not consist of these aspirations in consonants but is softer and rounder. Doubled-consonants are stopped with the tongue to create the proper affect and unfortunately Pomakov’s Italian was much too Americanized to pass for authenticity.

The set was quite lovely and spacious: on the left, the portrait of the Contessa Attavanti, and on the right an altar to the Madonna. The orchestral tempi were well chosen and the orchestra’s beautiful playing certainly overshadowed the inconsistent dramatic purpose of the Sacristan in the opening. Cavaradossi’s entrance was cavalier as tenor Mikhail Agafanov filled the stage with a handsome and testosterone-filled presence. The orchestral horns were brilliant at this moment and set the stage for the pure tenore affogato sound that is expected of Puccinian singing.

Tenor, Mikhail Agavonov

Tenor, Mikhail Agavonov

Although Agafonov has a tremendous upper tessitura, his singing was often not as legato as Puccinian aesthetics require. In his letters and the journals of singers with whom he coached, Puccini indicated that the legato line was to be carried “not from note to note, as in Mozart, but carried through every note in between the notes he had written on the page.” Simply, that means that his music requires an influx of portamenti, graceful sliding from note to note, which were not successfully applied to this production in its entirety. It was sung in a very strict manner, unfortunately, where the application of legato sul fiato (singing on the breath) means a very different thing for Puccini.

The woodwinds were precise in their entry to Cavaradossi’s first aria, “Recondita Armonia,” which was rather disappointing. For some reason, Mr. Agavonov seemed to sing more effectively during passages of Cantilena or Arioso rather than in a full-blown aria. This aria is where the first flickering of Cavaradossi’s passion begins to spark, its ultimate purpose being to cause the audience to fall in love with him, so that we may further relate to Tosca. Unfortunately, Agavonov’s expression failed to ignite the audience. The arias in Puccini should be sung with a completely spinning line and very little straightening of that sound, as in pure Bel Canto singing, however, this was not the case for Agavonov. It is a lovely sound but tends to lose in the middle and lower tessitura because of his straightened tones. These, on several occasions, even caused him to sing under the pitch. The orchestra, however, was excellent.