17 Feb 2008

Interview with Canadian Mezzo-Soprano, Jean Stilwell, and pianist, Patti Loach

“Quand je vous aimerais? Ma fois, je ne sais pas?” are Carmen’s first words of seduction.

Oct. 25, 2007, Sala Cecilia Meireles

I met the young gaucho composer Dimitri Cervo at the 2003 Bienal of Contemporary Music, where his works for solo flute and strings, Pattapiana [named for Pattapio Silva, a great Brazilian flutist who died tragically

young at the beginning of the last century] made quite an impression.

There’s still a hint of jest in the comparison, but it’s not without reason that Jake Heggie and Terrence McNally are mentioned now and then in opera circles as “the Strauss and Hofmannsthal of the 21st century.”

Incoming general director of Santa Fe Opera, Charles MacKay, has made clear he is “in the tradition -- I will not be an agent for radical change,” at the celebrated New Mexico summer opera festival, MacKay says.

Composer Frederick Carrilho was born in 1971 in the state of Sao Paulo, and has studied guitar and composition, most recently at UNICAMP in Campinas. His music has been heard at the recent biennial festivals of contemporary music in Rio, with the Profusão V – Toccata making a strong impression at the Bienal of 2007. We spoke in Portuguese.

October 23, 2007, Sala Cecilia Meireles, Rio de Janeiro

What makes the first visit to Guanajuato’s Teatro Juárez breathtaking is the suddenness of the encounter.

Oct. 25, 2007, Rio de Janeiro.

José Orlando Alves is a young composer, originally from Minas Gerais, but who spent many years in Rio de Janeiro, where he has been active for a decade with the composers’ collaborative, Preludio XXI.

In the long ago, when the best source of music reproduction in the home was a handsome piece of furniture, fitted with hidden audio components, and usually called radio-phonographs, my family had one — from Avery Fisher I believe — that had among its controls a switch labeled ‘presence.’

Uncut with Canada’s Mistress of the trouser-role: the multifaceted Kimberly Barber.

Glimmerglass Opera is in a watershed year. With the departure of Paul Kellogg, who had considerable success developing that annual festival, General and Artistic Director Michael Macleod has chosen to begin his tenure with a variation on the usual four-opera-season, namely a thematic collection of pieces based on the “Orpheus” legend. “Don’t look back” is the marketing catch phrase.

Almost thirty years ago a century old tradition ended with the last performance of I Maestri Cantatori.

Santa Fe Opera’s announcement August 10 that English-born impresario, Richard Gaddes, General Director of the company since 2001, will retire at the end of season 2008, took the local opera community by surprise.

The week just ended was certainly of historic moment in the world of North American opera companies.

Perhaps it is a sign that, at last, the countertenor voice has come of age in the hearts and minds of both audiences and the opera establishment.

Back in the early 1980’s two good ideas came to fruition: the much-needed new concert hall for Cardiff, capital city of Wales, and plans to hold within it the first “Singer of the World” competition.

Charleston, S.C. — For over 20 years it was two operas a season here at Spoleto USA, the all-arts festival brought to this cultural capital of the Old South by Gian Carlo Menotti in 1977.

It is every young opera singer’s dream.

On May 9th, when Santa Fe Opera finally announced that Alan Gilbert had left his post as Music Director of that company, a long-standing rumor was made official.

In 1966 Jørn Utzon was forced to quit as architect of the Sydney Opera House before it was complete. Next week, the first new interiors he and his son have designed will be revealed. Louis Jebb reports 07 September 2004...

“Quand je vous aimerais? Ma fois, je ne sais pas?” are Carmen’s first words of seduction.

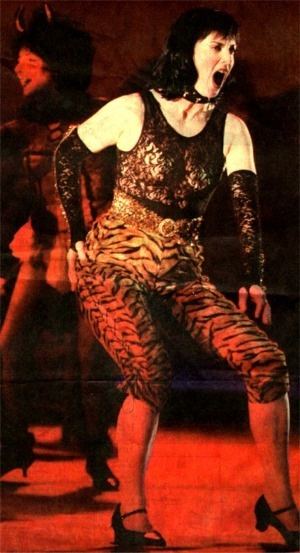

She uses them to affect those around her: Don José, her audience, and even the music itself. Since its inception, Bizet’s Carmen has remained an operatic staple, a birthmark in the standard repertoire, and since then mezzo-sopranos have fought to make the role of “La Carmençita” their own. But what of a tall, stunning, blisteringly seductive, and un-conventional Carmen? One who exudes more sex appeal by simply walking on-stage than so many other mezzos who have tried to seduce us as the vixen of Seville? In the mid-nineties, just such a singing-actress mesmerized her audience in Keith Warner’s production of Carmen for Opera Hamilton.

Canadian mezzo-soprano, Jean Stilwell, is internationally renowned for her portrayal of Carmen, and not simply because of her lush dark, merlot-like mezzo. Rather, the intoxicating combination of musicality, bodily instinct, and vibrancy on-stage, give Stilwell the label of a “singing-actress” of the dramatic likes of Callas. By embedding herself deeply within the heart of her character, Stilwell pulses with an air of verità and complexity. Not surprisingly, her dangerous Carmen has been seen in conjunction with the Buxton Festival, New York City Opera, and Welsh National Opera, to name but a few. Possessing a wonderfully distinct and powerful tinta colorato, that is required of the more dramatic mezzo repertoire, she has also performed the roles of Amneris in Verdi’s Aida and La Principess Eboli in his Don Carlos, as well as many others. Multi-faceted and equally at home on the concert stage, Stilwell is no stranger to these dangerous roles. Through them, she continues to enthral her listeners and retains dedicated fans on several continents.

Although Jean has been acclaimed for a significant number of other roles, it is with Carmen that she is undeniably connected, and rightly so. What is ever more fascinating about Jean Stilwell is the underlying and deeply rooted understanding that Carmen and she are more connected than we think they are; so much so, that one might say that Jean “is” Carmen, but Carmen is also Jean. For anyone who has had the pleasure of seeing Jean as Carmen, it would not be surprising to know that their blood flows in identical veins. They are so connected that Jean, along with the invaluable creativity and artistry of Canadian pianist, Patti Loach, has given rise to “Carmen Un-Zipped,” an opera-singer meets cabaret in a semi-autobiographical and deliciously realistic production where Jean exposes herself as much more than a striking, dark-haired diva with a few tattoos. She displays the beauty of the human heart and the strength of will one must possess in order to endure and survive the complexities of love, loss, and life.

Pianist, Patti Loach

Pianist, Patti Loach

Patti Loach has been musically inclined since a very young age and studied piano at the Royal Conservatory of Music and later at the University of Toronto. A multi-faceted musician, her interests are broad and diverse, from opera to cabaret, to tangos and jazz, and one cannot forget gorgonzola and vino rosso…specifically Wolf Blass Yellow Label; two little luxuries of life that helped to merge a friendship that would become an invaluable musical partnership. The friendship Patti forged with Jean Stilwell gave rise to this eclectic, invigorating, and refreshing production that has caused an artistic stir and the possibility of employing a new type of genre, where the operatic voice and music is used for expressive dramatic purposes other than those in which they were meant to be performed. “Carmen Un-Zipped” is the juxtaposition of life and art, a concept that artists and historians have attempted merge for millennia.

Today, I have the distinct pleasure of meeting with Jean Stilwell and Patti Loach to discuss the conception of their production, to talk about opera, and to delve further into ways that opera, a genre that has been seemingly associated with the upper-echelon of society, can be brought to the masses in an uncomplicated and more accessible way. Before the interview began, I was delighted to have been witness to a moving and quite effective performance of “Ne me quitte pas” with Jean, Patti, and Patti’s husband, trumpeter John Loach. The beautiful blend and emotional performance created the kind of passionate interplay that is necessary between musicians and everything was still for that few moments.

Mary-Lou: “Jean, Patti, thank you for speaking with me today.”

Jean: “Our pleasure.”

Mary-Lou: “I’d like to start with you, Jean. Every musician or singer has an interesting background; something or someone who ultimately influences his or her plummet into this fantastically difficult and rewarding field. Tell us, who your influences were, personal or professional. Who was the catalyst behind the artistry of Jean Stilwell?”

Jean: “My mum, Margaret Stilwell. She was a singer and she was a pianist. You know as Patti says in the dialogue to “Carmen Un-Zipped,” my father was an organist and a pianist and we had music going on around us 24/7. It was on all the time. You know, I would just watch her sing and I thought she was very, very beautiful. I thought she had the most perfect nose, you know (laughing). She was gorgeous and I loved watching her, and I was proud of her. I loved the colour of her voice. It was warm. There was no edge.

Patti: “It was described as creamy.”

Jean: “Yes, it was very creamy, very loving. Also, she was extremely humble. She would wear the latest fashions but I never ever knew that she was nervous. She would keep everything inside and she would just be a consummate professional every time, even when she was sick. I knew that she had the goods to have a professional career and she was offered that by Sir Ernest McMillan who was conducting the Toronto Symphony. He wanted to take her to London, England, but he took her to Carnegie Hall where she sang the St. Matthew’s Passion with the Toronto Symphony. She could have had that kind of career, but it was after the war and the priority was to have a family, you know, and so she had three kids and five-gazillion jobs: sang with the Festival Singers of Canada and had a church job. Her mother told her, “Just in case your music career doesn’t work, then you’ve gotta learn something, a skill.” She became a comptometer operator, which was a glorified adding machine.”

Jean: “I rarely saw her and when I did see her, I felt so lucky and she just seemed beautiful to me, until I got wise (laughing), you know, and then you grow up and see all the crazy things that make up a person. But yes, she was definitely my inspiration. My father, also, was a very fine organist, but he played the piano like an organist and we did not have a musical relationship. I mean we did in that he played a lot of Copland and Stravinsky and he played a lot of Bach and Handel all the time. On Sunday afternoons he would play Haydn and I hate Haydn…..

Patti: “Well, you have to wonder what came first. Did you hate Haydn because you just didn’t want to live with his music?”

Jean: “Probably, but actually I think I find Haydn boring. I loved when he would play things like the William Tell Overture and we’d all get on the couch and bounce around (Jean humming the overture and demonstrating)…we’d have just a riot when we were kids but, really I would say that it was my mother that was my inspiration.”

Mary-Lou: “And what of her, do you think, when you walk out on a stage, what of her do you take with you?”

Jean: “Her spirit. There is no question about it. She is definitely a part of me.”

Mary-Lou: “That’s wonderful, you know.”

Jean: “When I was growing up and was in my teens, I had no idea who I was and just did all sorts of crazy things. You try to find a personality, and our relationship was symbiotic, as most mother/daughter relationships are, because my mother really did live through me, as well. So, that was extremely difficult and I didn’t know who I was and it took me a long time to find out; a very late bloomer consequently. I also have a personality and spirit that is quite distinct from my mother’s but I know that she’s very, very present.

Patti: “You should tell the story about when your mother was doing vocal warm-ups on the piano bench and you sang them back.”

Jean: “I was about 18 years old and studying social work at Ryerson, and I wasn’t studying voice but piano….Lord knows why….and she said, “Jean, come here! Come here and sing this for me.” She pulled out some Schubert. I was in the church choir with he,r and I would just sing along and I would marvel at how she could find the middle note. She was a wonderful musician…she could play anything. So, she put out Schubert and played it and I didn’t like Schubert, but she said to me, “Ok, Jeannie, I want you to try and use your own voice and now sing for me again.” And, I looked at her and said, “Well, what do you mean, I am singing in the only way I know how.” She said, “Now don’t try and imitate me, just give me your own unique sound.” And I said, “I have no idea what you’re talking about. This is the only sound I know how to make. I’m not imitating you.” So, I started taking lessons. My mum asked around and I began studying at the Royal Conservatory with William Parry. I started with him. I auditioned for the Mendelssohn Choir and I had also just been accepted into the Ontario Youth Choir. I was going to sing Aaron Copland’s “In the Beginning,” and everyone was excited ‘cause I had only had 12 lessons and “I” was going to sing a solo! You know, “OH MY GOD. No one was gonna open any door for me cause “I” was in the Choral World.” (Laughing).

Jean: “Right before the audition, my mom came up to me and said (whispering), “Jeannie, I’m so sorry, I forgot to tell you that there’s going to be a sight-reading test.” And I said, (whispering) “Oh, no.” So, I sat there and as luck would have it a mezzo went in before me and she sang the sight-reading exercise and Ruth Watson Henderson was playing the piano, and was playing the notes and I memorized them. So, when I went in I sight-read and I made the same mistakes that the previous girl had made (laughing). I sang in the professional nucleus of the Mendelssohn Chorus and I was terrified. You see, my mother did all the solos so Elmer thought, “Well, if her mother can do it, she can do it.” My mother and I were the second alto section, complete. Anyway, in my first solo I cracked on a “D”. I was so nervous, and I thought ‘Ah Fuck.’ I was 18 years old. He didn’t ask me to sing another solo.

Mary-Lou: “What a story.”

Jean: “When I became a soloist and did Oratorio….you know the Festival Singers made a gorgeous sound and, you know, I loved being in the middle of a chord…I loved it. The first thing I did was the Poulenc “Gloria,” and I was right there in the middle of these nasty chords. That’s where I belonged, and I was young and a little overweight and I didn’t belong anywhere but there, in the middle of the sandwich. But then, I wanted to start to speak…to say something for myself and I knew that I had to move on. This was fine for mum but it wasn’t fine for me. The reason was that I was trying to find myself. I had a lot to say, but I didn’t know how. So, I joined the Tapestry Singers; then I did three operas in the Chorus of the Canadian Opera Company, and I thought, “Yes, acting.” I went to the University of Toronto to check out their program, but they didn’t teach any acting so that wasn’t right for me. Then I heard about the Stratford Festival, and I auditioned to get into the Gilbert and Sullivan productions. I got into the chorus and there was a full-time pay-cheque and there you go.”

Jean: “Patricia (Kern) said, “Well, you need an agent now.” So, I got an agent and then Vancouver called and saw that I had done all these roles. They got a cancellation and they were looking for a mezzo at the last minute. They wanted me for the role of Olga in Eugene Onegin in three or four days. THANK GOD the opera was in English instead of Russian. That was my first opera with Richard Margison as my tenor, Joan Watson was my soprano, and it was such a beautiful production with John Eaton as the director and I went on from there.”

Mary-Lou: “Patti, I’m going to ask you the same thing. You’ve also had a diverse background and began your journey into the musical arts at an early age, as well. Who would you say influenced you to proceed into what, for every musician, is a daunting and untrodden path?

Patti: “For me, I wouldn’t say that I encountered any leading musical influences in piano until I picked up Clarinet in public school. My first musical epiphany would have been at the Scarborough Music Camp. I was bumped into the senior band and I played the bass clarinet and they needed a bass clarinet…I would have been 12. Everybody warmed up and put their instruments together. The director put his baton down and said, “We’re going to do a B♭ concert scale,” and everybody played at the same time, and it was that first note that I thought it was such a huge sound and there were so many colours in that sound. As a pianist, you can pull colour from the piano, but there were so many colours in that B♭-major scale. What could be simpler, right? I remember just thinking I had died and gone to heaven. We did some great literature. There were many strong, young players in that band and we did Nimrod and to this day, if I’m driving and Nimrod comes on the radio I have to pull over and I cry every time. It was so moving to be a part of that, so I would say that it was strong influence. Because we do spend so many hours at the piano by ourselves, to sit in a group and be in a collective whole, to feel the power of the organism, was amazing for me. I don’t know, I had very kind teachers but the ones I found that were the most influential was to listen, really specifically, to Jazz pianists. Listening to where the note falls exactly in the beat; why does that time kick me in the gut when I hear it? Pianists like Bill Charlap, Hank Jones, Gene Di Novi, Bill Evans…thinking really seriously about touch. Why does this make me feel the way I do? Why loud, why soft? Also, trying to play their transcriptions, and getting to know things musically and technically, giving that sprinkle of pixy dust at the end that takes you into the realm magic.

Mary-Lou: “That’s really fabulous, but I’m going to ask you something else because you’ve brought me into that, and it’s about singing. For many, that word has many connotations. For some, it’s simply the practice of making sound with the voice, but for others it is a complete language in itself. Throughout history, instruments have been created and performed in an attempt, I think, to mimic the fluidity, range, depth, and subtleties of the voice. One often hears, “Make the line sing.” We think of Bach fugues with vocal fachs in mind to bring out particular colours. When you play with a singer, Patti, what do you feel the pianist’s duty is and what is it, for you, that creates the kind of collaboration you have with this singer and this particular voice?”

Patti: “First of all, I have to say I’m so extremely lucky to work with this singer, and whether or not she knows it, I spend a great deal of time looking at the back of her body, as most pianist do when they accompany singers. We’re talking about an extremely physical singer. Jean sings with her entire body and I can tell by the set of her ribs or the way her muscles are tensing down here (gesturing to lower back) what’s going to happen. I can tell by her breathing, and I have to say that I haven’t worked with bad singers, but I would imagine it would be hard to work with a singer if the breathing wasn’t as good as hers is. It all starts with the intake of the breath and the preparation of the body. If a singer isn’t breathing in a way that you can read…cause that’s an aural cue, you can sense it. For example, in our show, we both wear microphones and we didn’t always practice with the microphones on and anyway, one time we finished a phrase and were about to begin the next phrase and I took a breath, and she turned around and said, “What was that?” and I said, “Oh, I think it was me!” (Jean breaks out into a hearty diaphragmatic laugh). It was just me, ‘cause I was breathing with her, right? It makes things so much easier to shape a phrase when you’re working like that. You know, Glenn Gould was a huge influence on me and I guess I’ve always thought about voices. Maybe that’s why I like working with a mezzo so much, because she can sing in that netherworld, as well. When I find music for piano, I look for music especially that has a well-promoted inner-voice because I don’t want to double anything she’s doing. The thing with Jean is that she never does anything the same way twice. So, I listen really hard.

Jean: “I really make her work.”

Mary-Lou: “For you, Jean, the idea of singing. The voice is such an enigma and we try to define it or give name to it but it seems impossible because it’s so personal an instrument. It’s so unique and everyone’s is different. You can hear, even on the radio, distinct qualities that define the voice as Jean Stilwell’s or Leontyne Price’s. You can tell if it’s Callas or Renata Tebaldi. What do you think about this language of singing? How do you define the language of singing?

Jean: “Oh, extremely personal. It is a language that conveys the truth, but no matter what, the audience knows exactly what’s going on because they feel. They might not be able to define it but they watch and they feel what you give them. So, if you’re nervous, if you’re upset, if you’re angry…whatever, the audience senses it, even if you don’t mean to portray that or communicate that. The voice is “this” (gesturing near her heart and with hands in an opening motion). My teachers talked about opening up your chest and just exposing, and that is the truth. The goal is to be that, and to stay there, and express the words and the music, which are equally important; and so, I would have to say it’s just about the most vulnerable instrument. No matter what sound you make, it reveals the truth.

“The voice is the most vulnerable instrument. No matter what sound you make, it reveals the truth.” Jean Stilwell.

Mary-Lou: “I agree…..what about Carmen’s truth? Talk to me about Carmen. Why her? Why you? What is it about Carmen that spoke to you, because obviously, she has spoken to you and I think, now, that with this production you are speaking through her, as well.

Jean: “Well, I would have to say, first of all, because she’s so powerful. Carmen really is incredibly courageous. Carmen is an animal. She doesn’t think…she’s smart, but she sings with her body and that’s what I do. She has a great sense of humour, and here’s a biggie: that freedom. That’s huge. I’m a claustrophobic and even if I put on clothing that’s wrong…you know I hate hats. Carmen would never wear a hat ‘cause it encloses her. She’s a nomad. A singer is a nomad, and yet people think that Carmen is the leader of the pack and this kind of stuff. She would never say, “You know, fuck men.” Carmen knew exactly what her place was but she was very clever in trying to achieve it. You know, in the play she achieves it for her husband and for the pack. She doesn’t do it just for herself, and that is blood. If you’re a gypsy, no one else can possibly come into your life. You know, we were in Budapest and I was the train station and you see the gypsies. There’s no interacting. There is no notion that they’re welcoming or that they want you to go up to them. So, I think that this is really what I loved about her; also, the fact that she loves to laugh and dance and she celebrates her body. She loves passionately, but does she…does she know? She says she’s in love, but is she? She doesn’t even know, because she’s not that clever. You know other people interpret, but what do we know…it’s like the Beatles. People listen and they say, “Oh, they’re talking about LSD in that Beatles tune,” and John would turn around and say, “Hey were just some ordinary guys. I don’t know, you know…whatever.” That’s exactly, you know…she does it and you interpret it.”

Dialogue from “Carmen Un-Zipped”

Courtesy of Patti Loach.

“What lies in the belly of Carmen is her ferocious hunger for freedom. She has so much to teach us about loving, living, and choice…

Carmen is a part of me.

She has inspired me during seminal moments in my life: falling in love, marriage, the death of my mother, the birth of my son, the end of my marriage, relationships and break-ups, and then some…

Carmen has been the one single thing in my life that has given me courage. Well, Carmen, and my son…

Every time I sing Carmen, I fall in love with her all over again.

Jean: “I had a most spectacular time doing Carmen in Pittsburgh. I was doing a very traditional production of Carmen but the director had flown in some flamenco dancers from Caracas and these girls were so hot, they were so earthy. They were such an education to me. They were Carmen. They were all Carmen. The great thing was that they wanted me to go out with them. They wanted me to celebrate and on-stage in the scene in Lilas Pastia’s Tavern, they would urge me toward them and I was just (Jean motioning to grab their imaginary selves). You know they were just urging me to “Give us your crotch,” you know, like “Come on. Give us the earth.” That felt sexy. That felt hot. She’s an animal and I can relate to that. In fact, the very last Carmen that I did, the director said to me, “So, how do you want to do this,” which was extremely flattering, and I said, “Well, instead of me portraying Carmen, why don’t we do it as if Carmen is portraying me.” “Show me,” he said. So, that’s how I did it. Carmen was a little more vulnerable. She was playful. She was “really” angry and she showed her anger more. She comes in from the side….I don’t. My Carmen was a little more in your face. She’s a gypsy and she had to provide…she had to get the money and she was the best at what she did. It was her job. The guy was still the hierarchy, however, and she still bowed to the man. A lot of people think that Carmen is the ultimate feminist, but I don’t think so.”

Mary-Lou: “So, let me ask you this, as a musicologist, I’ve studied Carmen in many different perspectives, but let’s say in a more historical, theoretical, philosophical methodology. I love what you’re saying and I think she is really, in a musicological sense, one of the most complex characters. I mean, if you have to stand in front of a group of students and lecture to them about her, it’s difficult because she’s so hard, she’s so dangerous; but yet, she allures us all. We want her. We want to be seduced by her but then we ultimately crave her death. We attend the opera already knowing that José is going to murder her. He’s going to murder her. He’s going to penetrate her with his knife. It’s a different death than a Mimì or a Manon Lescaut where it leaves a gaping hole in you, and you cry and you leave. With Carmen, for some reason, and I ask my students this, “Do you feel that gaping hole?” Do you pity her? Do you cry for her? She knows exactly what she’s doing. It’s so hard to define her because she’s such an awesome character, and I don’t mean awesome as in cool…but that you can’t put her in a box. You know, the death, for historians, is one thing, but then we also ask, does she ever really have sex with anyone, because we often don’t ever see her having sex. Does she just tease?”

Jean Stilwell

Jean Stilwell

Jean: “It’s up to the director. It’s often up to you…it’s your playing field. Is she in love with José or no? Is she in love with Escamillio, or no? It’s your playing field, and you get a choice. You find it in the music and in the words. I’ve done it in several different ways. For example, in Hamilton I thought the tenor was so fucking hot and then I went to Pittsburgh…”

Patti: “Did she have sex on-stage with that tenor, or didn’t she? I mean, to what extent is that decision made by the casting specific to a production?”

Jean: “Well, it does, a lot. I think that….it seemed like we did because we had that passion for one another. I took the same production to Pittsburgh and this tenor was very different. This tenor was a maniac. We didn’t get along very well. The director came up to me and said, “You don’t like him do you?” And I said, “No,” and he said, “Show me.” I loved it. Oh my God.”

Jean: “If Carmen shows fear when she confronts José in Act IV, then we would fear for her too. If she faces José knowing, in her heart of hearts, that he’s going to murder her, because she refuses to be put in an emotional straight-jacket by him, then perhaps we should feel sorry for her; less afraid for her. She knows she’s going to die and that José is going to do it. She read it in the cards. She feels a very powerful connection to José because of that; because of his dark side; because she, too, has a dark side. Do we crave her death, or do we want her to find joie de vivre with Escamillo, for however long? I don’t think her state is pathetic. It is her choice to die. Her raison d’être is freedom, so she has no choice. She accepts her fate and honours it, and it is who she is. What is sad for me is that there is no way out for her. In dying, she becomes free rather than rage that this is the choice she has to make. She wants to be with Escamillo and risks her life to do so. That is because he offers her life. Why else does she go to the bullfight if she doesn’t think she has a chance at life with Escamillo? She knows that José is going to kill her, but she doesn’t know when or where. Maybe, just maybe, there’s a chance with Escamillo. It is Frasquita who warns her that José is there, and suddenly then everything changes. Carmen is, and she is not a victim. So, I RAGE for Carmen. Their exchange begins and she wants desperately to get away. She feels caged in and so she lashes out. She is in the moment. “Just fuck it and get it over with because being her with you is death. Kill me so that I may be free. Fuck you. I’m not afraid. I am fucking angry. Come on, come on, and do it. I dare you, you fucking coward.”

Jean as “La Carmençita” in the Opera Hamilton Production of Bizet’s Carmen

Jean as “La Carmençita” in the Opera Hamilton Production of Bizet’s Carmen

Mary-Lou: “Let’s talk about “Carmen Un-Zipped.” Patti, tell us what inspired this production and collaboration.”

Patti: “We had done a show together called “Love and Life” that centered on Schumann’s Frauenliebe und Leben, and that urged a lot of conversation between us. We were looking at ideas for a show we could do together that would incorporate many elements, such as: That she’s more classical and opera and I’m classical, but also cabaret and musical theatre, and jazz. We wanted to incorporate all of this and it occurred to me, over many evenings of gorgonzola and Chianti, by listening to these amazing stories from Jean, that we should just build a show around them. These stories aren’t just specific to a singer, they’re stories of all women and men who have fallen in love, fallen out of love, experienced the joy and wonder in the birth of a child, the loss of a beloved parent—these are stories that resonate for everyone. Jean unzipped my perceptions of what a diva is all about, and hence… “Carmen Un-Zipped.”

Mary-Lou: “And why did you think it would work? What ideas for promotion did you conjure up and why a cabaret act?”

Patti: “I knew the show would work because it addressed what is human in all of us and I was working with one hell of a singer, who was ready to take some serious risks. Whenever I sit in an audience, I want to be challenged as well as entertained. I want to hear a story that is truthful, not maudlin. I want a story that will make me look at myself as well as the performers. Therefore, when I sat down to cull through all of Jean's stories, I kept all of that in mind: I assumed our audiences would be curious and intelligent and demand excellent music, excellently performed. Plus, we've discovered some beautiful music along the way, the songs of the New York Singer/songwriter/pianist John Bucchino. Singing Bucchino's music is what we do to reward ourselves at the end of a rehearsal. I have the most beautiful memory of being in a gorgeous, ancient house in Orvieto, Sicily. Jean is singing; I'm playing a beautiful old grand piano; the floor to ceiling windows are all thrown open, and all we can see out the window is blue, blue sky. We finished our rehearsal, and toddled down to a restaurant by the sea where, in typical Italian fashion, the tables on the patio were crowded together. The Danish people at the next table found out that Jean was a singer, and it turns out that while we had been rehearsing, that afternoon, they had been walking around the streets, heard us, and had stood for about 20 minutes looking up at the open window, listening.”

Mary-Lou: “The relationship between a singer and pianist is one that, I feel, is an extremely intimate. There is something about supporting a voice that has a much different sensation altogether from supporting an instrument. The roles of the singer and pianist have been changed and enhanced since the inception of Lieder and, really, they are equal roles. The collaboration is as strong as both partners are dedicated to their performance and each other. Talk to us about your collaboration; how your diversities, as well as your similarities, reflect upon the success of “Carmen Un-Zipped.”

Patti: “Stephen Sondheim was once asked how to make a musical collaboration work and he said, "Make sure you're writing the same show." I like that. I'm constantly checking with Jean to define a direction, either within a song or when I'm working on writing dialogue, and I'll say, "Is this what you want", or "I think this line is important", or "Are you sure you want to share that?" Musically, although we have a partnership, I know that Jean as the vocalist has the audience's ears and eyes (Damn it). So, when push comes to shove, singer trumps piano. It has to be that way. Luckily, for us, I don't think she's ever had to play the trump card. We're pretty much on the same page when it comes to the music. We're tight.”

Carmen Un-Zipped: Jean Stilwell and Patti Loach

Carmen Un-Zipped: Jean Stilwell and Patti Loach

Mary-Lou: “Jean, let’s take a bit of a controversial road and discuss an issue that continues to fascinate many, and that is the comparison between opera singers of today and those of the past, say 70 years. When we listen to a Leontyne Price, or a Callas, Tebaldi, a Schwarkopf, a Jussi Bjorling or a Moffo, and then listen to a Renée Fleming, an Anna Netrebko, a Ramon Vargas; let’s say, and a Natalie Dessay. We continue to hear those voices of the past as remarkable, and there is no question that they were. Do you feel that voices have changed? Has this genre mutated into a competition of physical beauty and looks and suffered in terms of the actual music making?”

Mary-Lou: “Perhaps, more specific to you, Jean, the mezzo’s of the past and today: Barbieri, Cerquetti, Simionato, Horne, Larmore, Von Otter, Bartoli, Graham, Mishura, Troyanos, Baltsa, Zajick, Borodina…tell us, what you think defines these voices, and yours included. There is something unique in them, but also very similar and for many mezzo’s, as we know, the controversy over “voce di petto” (chest voice) prevails. What do you think about these voices and how they employed the dangerous mystery that surrounds the mezzo fach.?”

Jean: “To each his/her/own. We, each of us have something to say, otherwise we wouldn’t chose to sing. The challenge is to find the route to the depths of our self-knowledge and awareness. To sing requires great courage. We are totally naked, no matter of emotional awareness. Each of these singers had to find their own path and make their own choices based on their emotional make-up. They are all extremely, emotionally huge. I respect each of these singers and the choices they made because they made them. They dared to go there. Yes, I have my favourites, but these choices are because I feel the greatest connection and admiration for them. I have different reasons for admiring each one.

“I never liked Horne. I found her voice ugly no matter the brilliance of her technique. Simionato was awesome. What an actress! Larmore has a beautiful sound but is too emotionally soft for my liking. I only saw her in recital once, so perhaps it is unfair of me to judge. I am INSANE for Von Otter. I admire her as a woman. I love the colour of her sound. She is all about colour and finding colour from an intellectual perspective. I admire her lifestyle, her intelligence, her groundedness, and her discipline. These are all things of which I wish I had more of. Troyanos was a mental case, and I adored her. I wanted to take her in my arms and love her. She was so vulnerable and for that, I fell in love with her. I adored her Octavian. I loved Baltsa’s balls, but I would never choose to sing like her. Her singing was vulgar for me. Yet, I loved her animal-like behaviour. I thought her Carmen was fabulous, but that’s all. Zajick blows me away. She’s an awesome power house! I get off on her largess. That’s it. I, at one time, wanted to have a voice the size of Zajick, but now I simply admire her for what she does. I respect Bartoli but I’m not into her repertoire and so I spend little time thinking or listening to her. I do admire the depths to which she researches her fach. I respect her intelligence. My choices are sooooo emotionally charged. So, there you have it!

Mary-Lou: “I’d like to ask, Patti about the cross-over genre that manifested itself years ago now. What do you think about this genre and do you think it has served a purpose? For some classicists, they would say, well, it may bring a more popular based audience to the opera and to classical music, and for popular critics they see these singers as “opera singers” which to me indicates a well-trained voice, and a specific ability. What do you think about it?”

Patti: “Music is personal. It's subjective, so it's hard for me to comment on that. I listen to EVERYTHING with an open mind and I leave it up to the performers to turn me off or on. For example, Jean and I went to see the East Village Opera Company a couple of weeks ago: they do classical arias with rock band arrangements. The singers are not specifically classically trained opera singers; they're musical theatre or rock singers. For me, that show really brought home the fact that there are so many beautiful melodies and gorgeous harmonies in the arias in opera. Should those arias live only in opera halls? I don't think so. Do classically trained singers have the right to be territorial about that music? I don't think so. These arrangements were creative, and the performers were well rehearsed and passionate and they told the story. Some of it I loved, some of it I didn't love, just like ANY live music performance. We've all sat in an opera hall and rolled our eyes at scene chewers. My point is that there is good and bad music everywhere, but I leave it up to the listener to make his own decisions. Both Jean and I LOVED the Habanera that the East Village Opera Company performed. Every Carmen is different.”

Mary-Lou: “Indeed, and I would like to thank you both, on behalf of Opera Today, for this enlightening and exciting interview. The best of luck to both of you in all your future endeavours.”

Jean Stilwell and Patti Loach

Jean Stilwell and Patti Loach

Two wonderful women, consummate musicians and a few lessons for us all. Musical partnerships of this sort are special, indescribable in words, and really only understandable when one can be witness to their magical properties in performance, through the language of music. Jean and Patti’s musical connection is supported by a tremendous friendship, which makes this collaboration even more wonderful to observe. A good model for all singer/pianist relationships; when you find this irreplaceable musical partnership, hang on to it and don’t be afraid to look at your colleague every so often and say, without speaking….Ne me quitte pas.

By Mary-Lou Patricia Vetere, 2008

PhD (ABD), M.A., Mus.B

For more on “Carmen Un-Zipped” or Jean Stilwell please visit: www.jeanstilwell.com or www.pattiloach.com CDs available, please see websites