May 29, 2008

Is there a Right way to sing opera?

Igor Toronyi-Lalic [Times Online, 30 May 2008]

Igor Toronyi-Lalic [Times Online, 30 May 2008]

There’s so much that Kim Jong Il would love about the Barbican. All that delicious rolling, rising, falling, state-funded concrete, the Gesamt-kunst thrust, the communal togetherness, the cheesecake. And the opera. A recent spate of new works had enough anti-Americanism/imperialism/capitalism to warm the heart of the frostiest commie dictator.

Shorter, sparcer ‘Dido’ opera will leave audiences satisfied

By Keith Powers [Boston Herald, 29 May 2008]

By Keith Powers [Boston Herald, 29 May 2008]

If you hear local culture-lovers saying things like “rosy-fingered dawn appeared” or “I sing of arms and the man,” smile graciously and nod. We’ve had a heavy dose of the classics here lately, and it’s bound to have an effect.

Der Rosenkavalier, Coliseum, London

By Andrew Clark [Financial Times, 29 May 2008]

By Andrew Clark [Financial Times, 29 May 2008]

If the success of an opera company is judged by the input of its music director – usually a pretty accurate measure – then English National Opera has had a good season.

NYC Health Department: Mice at Met Opera

By RONALD BLUM [Associated Press, 28 May 2008]

By RONALD BLUM [Associated Press, 28 May 2008]

On-stage villains aren't the only vermin at the Metropolitan Opera.

The grand theater at Lincoln Center, where much of New York's society gathers to show off gowns and jewels, has been cited for sanitary violations by the city Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

May 28, 2008

Jonathan Miller's Operatic Mission

By NICHOLAS WAPSHOTT [NY Sun, 28 May 2008]

By NICHOLAS WAPSHOTT [NY Sun, 28 May 2008]

Lunch with director Jonathan Miller is in turns a testing lecture on philosophy and literature, a hilarious stand-up routine, a somber poetry lesson, a doleful diatribe against trends in opera production, and a lugubrious harangue against celebrity culture and vulgarity. Above all, it is a superb one-man show.

Mezzo-Soprano's Glorious Debut Lifts 'Cavalleria'

By Anne Midgette [Washington Post, 27 May 2008]

By Anne Midgette [Washington Post, 27 May 2008]

Dolora Zajick, 56, has long been the reigning American mezzo-soprano. She is a fixture at the Metropolitan Opera, where she is unequaled in the major Verdi roles (Amneris, Azucena, even Eboli).

Il prigioniero/Bluebeard’s Castle, La Scala, Milan

(Photo: Marco Brescia, Archivio Fotografico del Teatro alla Scala)

(Photo: Marco Brescia, Archivio Fotografico del Teatro alla Scala)

By George Loomis [Financial Times, 27 May 2008]

It was good to pair Luigi Dallapiccola’s Il prigioniero with Bartók’s Bluebeard’s Castle but then it was good to revive Il prigioniero period, even if this one-act opera by the most lyrical of Italian dodecaphonists was staged just last month at the Paris Opera.

Tree-mendous in Chicago

And it did so with a completely different take on the piece than that devised by Peter Sellars for Vienna’s world premiere in November 2006 at the Festival of New Crowned Hope.

The original concept had the large orchestra on stage, with minimal stage action relegated to small elevated playing spaces, more semi-staged oratorio than a full-fledged dramatic rendering. It is perhaps no accident that this Chicago company has “theater” prominently included in its name, for they have put the band back in the pit, and with consummate stagecraft, they fleshed out this folk tale’s libretto which was crafted by Sellars and the composer based on a story translated by A.K. Ramanujan from the Kannada language of southern India.

The king (James Johnson, dancer).

The king (James Johnson, dancer).

The tale concerns two sisters, one of whom, “Kumudha,” is able to

transform herself into “A Flowering Tree” and back again. However, her

jealous sibling’s wicked friends break the spell, trapping the heroine in

her tree-state, breaking her limbs, and leaving her in the gutter as a

pitiful grub-like torso. After her disappearance, the “Prince,” having

already wedded her for her bewitching beauty and powers, wanders

disconsolately until his love restores her and reunites them in marital

bliss. The only other singing principal is a “Storyteller.”

The minimalist set and costume design by George Souglides scored big, with simple yet highly imaginative effects. The first important transformation scene was accomplished with “Kumudha’s” sister (dancer Karla Victum) stretching hidden, over-long sleeves from her costume and extending and twisting the “branches” into various shapes. Each subsequent transfiguration was larger then the previous, magically accomplished with colored ropes.

Whether descending from the flies or rising from the stage floor, these were presented in artfully tied designs that would be the envy of any advanced macrame class. Indeed, the curtain rise of Act Two stunningly coincided with a “growing tree” emanating from “Kumudha” down center stage that ultimately filled the entire proscenium opening. The few set pieces and props (a veil-covered over-sized wedding bed, a gilt throne, primitive masks on poles) were selected with attentive care.

The Storyteller (Sanford Sylvan).

The Storyteller (Sanford Sylvan).

The evocative and colorful costume design was effectively based on

traditional Indian and Asian street and stage garb, with a couple of the

specialty dance turns being dazzlingly outfitted. I wish that same attention

had been lavished on our heroine, who looked quite plain; well, too plain by

comparison. Indeed, the rather lumpy and shapeless white coat she wore in the

wedding scene was promisingly removed to reveal only more of the same look,

if better fitted. All of this was well-served by Aaron Black’s terrific

lighting, artfully combining lustrous washes of color with well-calculated

and flawlessly executed specials, gobos, and area lighting.

If all this was gorgeous to behold, it would not have impacted us as strongly as it did without Nicola Raab’s masterful direction. First, without ever unduly cluttering the stage, Ms. Raab has devised meaningful and poetic movement for the large chorus and corps de ballet. As we entered the theatre, the white-garbed “Storyteller” was already seated, immobile on a chair stage right. Slowly, the chorus in reddish-orange filed on from various points and seated themselves on the stage around him, ultimately creating a visual “island” that captivates us before a note is played. We couldn’t wait to hear what he has to say.

Similarly, meaningful character relationships are defined with ethereal subtlety. The mating scene with our newlyweds walking/stalking on the bridal bed was a study in sensuous restraint, as the pair never quite touched but conveyed the impression of love-making nonetheless by tracing the head and torso with slow sweeping gestures, and intertwining their arms (well, almost) in ever inventive combinations.

Perhaps the most problematic scene of all, the dismemberment of the tree-trapped “Kumudha” was beautifully solved by having two dancers wrap her in a cocoon of a vibrant red cloth. Leaving one arm free, the actress could recline, sit up, and drag herself around the stage as a sympathetic outcast.

The ritualistic choreography by Renato Zanello was well-executed by not only his trained dancers, but also pleasingly performed by the singing chorus. The clean, thrilling choral work (most of them are in the COT Young Artists Program) was complemented by the group’s exceptional ability to transform themselves at will from commentators, to bystanders, to relatives, to royal subjects, all the while doing some amazing staged business, not the least of which was crawling from the wings on their bellies to pick up folded boards that were used in any number of combinations to create everything from a village of houses to a penultimate pop-up back-drop for the lovers’ reunion.

COT assembled a fine trio of singers as its principals. Natasha Jouhl proved an affecting “Kumudha,” singing with a well-schooled, ample lyric soprano that easily encompassed all the wide ranging demands and soaring lines of this difficult role. Originally written with Dawn Upshaw in mind, the part was taken over in Vienna (and several other locations) by rising star Jessica Rivera (who recently triumphed locally in another Adams piece, Chicago Lyric’s “Dr. Atomic”). Dawn and Jessica are two artists who really “get” this music and don’t just sing it, but embody it. That said, although she vocalized it splendidly, looked attractive, and acted with commitment, I did not yet feel that Ms. Jouhl has fully integrated the piece into her voice, or more particularly, her artistry. I would love to see her again after she has the experience of some more performances.

With Noah Stewart’s “Prince” I felt that we were experiencing an artist on the verge of a major career. He brought a regal bearing to the portrayal, and a polished, weighty lyric voice with excellent thrust on the high phrases, and wonderful presence throughout the range. Excellent diction, handsome good looks, beautiful instrument, wonderful musical instincts, sound technique, stage savvy — he’s got the goods.

I have long admired the fine artist Sanford Sylvan, but I found that his soft-grained approach was initially a little too lieder-based and subtle for the task at hand as the “Storyteller.” Seated a third of the way upstage for the first act, while I could hear his beautiful sounds and sensitive phrasing, I too often had real trouble understanding the text and found my gaze drifting to the surtitles. When he came forward to the side of the proscenium in Act Two, there was an immediate difference. This would be a quick fix by just telling him to “Sing out, Louise” when he is upstage. Still, he is a treasureable baritone and was an audience favorite.

Kumudha (Natasha Jouhl) and the Prince (Noah Stewart).

Kumudha (Natasha Jouhl) and the Prince (Noah Stewart).

Diminutive Joana Carneiro had taken over conducting duties from Mr. Adams

and this was a tour-de-force assumption. “Tree” is a monster-piece that

calls for split second rhythmic changes, quicksilver mood-altering shifts,

lyrical outpouring, percussive tirades, and well, the kitchen sink just may

have been in there somewhere. Above all, this stuff must be clean-clean-clean

to make its hypnotic effect and save a few squishy moments in the opening

bars’ undulating strings, Ms. Carneiro was in full command of her forces.

As if she was driving a car at 120 miles an hour, there was no room for

error. And she negotiated every twist and turn of this challenging piece with

concentrated inspiration. Brava Maestra!

It seems as though Mr. Adams may have developed the score a bit since Vienna, where I remember thinking that perhaps the heroine should have a set piece up front to announce her character. It seems that “Kumudha” had more exposition to sing at COT. Or maybe the staging was just that much more compelling. For all its glories, and they are many and they are ravishing, I still found myself wishing that the long chanted choral dance in Act Two (sort of Rap-Lite) was a bit shorter. And I sorta wanted a radiant final duet for the reunited lovers. Have I seen “Turandot” too many times? Perhaps.

Still, this was in toto a welcome and notable achievement. Chicago is a world class musical city and with Chicago Opera Theater’s “A Flowering Tree” we have been treated to a sampling of the very best the town has to offer.

James Sohre

image=http://www.operatoday.com/a-flowering-tree.png image_description=Kumudha (Natasha Jouhl) transforms into a flowering tree [Photo by Liz Lauren] product=yes product_title=John Adams: Flowering Tree product_by=Kumudha (Natasha Jouhl), Prince (Noah Stewart), Storyteller (Sanford Sylvan). Conductor: John Adams (May 14,17); Joana Carneiro (May 20, 23, 25). Director: Nicola Raab. Choreographer: Renato Zanella. Production Designer: George Souglides. product_id=Above: Kumudha (Natasha Jouhl) transforms into a flowering treeAll photos by Liz Lauren courtesy of Chicago Opera Theater.

Revised Amistad makes its mark

Happily, a constellation of circumstances caused Nigel Redden, general director of Spoleto USA, to see Amistad as an ideal work for the 2008 season of the Charleston, South Carolina, festival.

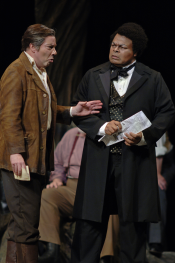

Amistad tells the true story of a Spanish ship taking captive Africans to America to be sold as slaves in 1839. The Africans mutinied, killed most of the ship’s crew and intended to return home. Misguided by the surviving navigator they landed on Long Island. The Spaniards demanded their return, but the still young United States was sharply divided on what action should be taken. The Africans found an eloquent defender in former president John Quincy Adams who pleaded their case before the Supreme Court. Two years later they were released from jail and allowed to return to Africa.

And the circumstances at Spoleto USA? Charleston, commercial and cultural center of the old South, was the epicenter of the slave trade, which — although outlawed by Congress in 1808 — continued illegally. The city’s slave market is maintained as a museum that recalls painful past history.

Stephen Morscheck (John Quincy Adams)

Stephen Morscheck (John Quincy Adams)

The site for Amistad was the totally reconstructed Memminger Auditorium, a

1939 building devastated by Hurricane Hugo in 1989. Once the city’s major

performing arts venue, the building stands at the edge of a mixed

neighborhood near the historic heart of Charleston. What better work to

pinpoint Charleston on the historical map than Amistad?

Redden insisted upon major revision of the score and he, along with Spoleto director of opera and orchestras Emmanuel Villaume, played an active part in the project. With their help Davis and his librettist cousin Thulani Davis made Amistad an opera much leaner, more focused and dramatically far more effective than the original. And in so doing they created not only a masterpiece of American opera, but further a work that — against a contemporary horizon darkened by undercurrents of racism — resonates today far beyond Memminger and Spoleto USA.

The Davises eliminated characters and scenes, and the composer reduced the orchestra from 65 to 45. Amistad — now only slightly more than two hours of music — is a work transparently coherent both in narrative and music, and Spoleto assembled a creative team and cast that made the work, seen at its premiere on May 22 and again on May 25, an opera that should be widely performed. Amistad now has a mass hero of eight Africans, each with significant solos. As their leader Cinque, bass-baritone Gregg Baker was a commanding presence on the oblong Memminger stage, and as Margru, soprano Janinah Burnett gave a poignant account of how women were treated by their captors. It was followed by the overpowering chorus “Ankle and Wrist,” referring to the chains the Africans had worn.

Gregg Baker (Cinque) and ensemble.

Gregg Baker (Cinque) and ensemble.

Tenor Dennis Petersen led a quartet of reporters out to exploit the

Amistad case as a public sensation, while tenor Brian Frutiger brought

passion to forces advocating abolition of slavery. Bass-baritone Stephen

Morscheck, tall and lean, was an imposingly agitated ex-president Adams in

his confrontation with the Supreme Court.

Davis has woven hints of jazz, blues and even scat so seamlessly into the score that they surrender their identity to his uniquely personal idiom. His use of the hymn “Jesus Savior, Pilot Me” is one of the most moving moments in the opera. Thus the dialectic of American history — the commitment, on the one side, to free men and, on the other, the acceptance of slavery despite the noble wording of basis documents — played out before the Memminger audience. The Davises brought a mythic gloss to Amistad by placing the story of the ship and its captives in the hands of a pair of deities from African mythology. As the Trickster God tenor Michael Forest, both narrator of the story and participant in it, had the lead role in the huge cast, while Mary Elizabeth Williams brought humane concern to the Queen of the Waters with her warm and winning mezzo.

Director Sam Helfrich, set and costume designers Caleb Hale Wertembaker and Kaye Voice, and lighting designer Peter West collaborated to make Amistad flow with ease across the stage in Memminger’s black-box interior. Indeed, the production is a coup of music theater for Spoleto — an experiment in opera grand and intimate and timely in its content. The trial that consumes most of the second act is a superlative achievement of dramatic narrative that reaches back to the beginnings of slave trade and culminates in a vivid reenactment of the mutiny on board the Amistad.

A major contributor to the success of the production was conductor Emmanuel Villaume. Working — he noted — as the many-armed Indian god Shiva, he led his gifted ensemble of young instrumentalists through Davis’ complex score, unfazed by its multiple meters and shifting rhythms to bring musical and dramatic drive and continuity to this compelling story.

Janinah Burnett (Margru), Herbert Perry (Burnah), Norman Shankle (Kaleh), Mary Elizabeth Williams (Goddess of the Waters), Crystal Charles (Captive).

Janinah Burnett (Margru), Herbert Perry (Burnah), Norman Shankle (Kaleh), Mary Elizabeth Williams (Goddess of the Waters), Crystal Charles (Captive).

It is significant that the Spoleto revival of the revised Amistad comes less than a month after the world premiere of another opera that confronts the question of slavery in the years prior to the Civil War: Kirke Mechem‘s John Brown’s Body, premiered by the Kansas City Lyric Opera on May 3. Both works call for careful reconsideration of truths long — and uncritically — held self evident.

It is of interest that while most of the Amistad captives returned to Africa, one — a woman — stayed in this country and earned a degree from Oberlin College.

The 2008 season of Spoleto USA runs through June 8. Visit www.spoletousa.org.

Wes Blomster

image=http://www.operatoday.com/lrg-290-img_1412.png image_description=Gregg Baker (Cinque) and Fikile Mvinjelwa (Antonio) performing in Amistad at Spoleto Festival USA, May 22- June 8, 2008. Photo by WIlliam Struhrs. product=yes product_title=Anthony Davis: Amistad product_by=The Trickster God: Michael Forest; Navigator: Raúl Melo; Don Pedro: Jeffrey Wells; Kinnah: Robert Mack; Grabeau: Kevin Maynor; Burnah: Herbert Perry; Margru: Janinah Burnett; Bahia: Kendall Gladen; Kaleh: Norman Shankle; Captive Girl: Crystal Charles; Cinque: Gregg Baker; Lieutenant: Edward Parks; Antonio: Fikile Mvinjelwa; Reporter 1: Dennis Petersen Reporter 2: Zachary Coates; Reporter 3: Jan Opalach; Reporter 4: Jonathan Green; Phrenologist: Dennis Petersen; Abolitionist Tappan: Brian Frutiger John Quincy Adams: Stephen Morscheck; Judge: Edward Parks; Goddess of Waters: Mary Elizabeth Williams; Ship Cook: Brian Matthews. Director: Sam Helfrich; Conductor: Emmanuel Villaume; Assistant Conductor: Olivier Reboul; Accompanist: Lydia Brown; Costume Designer: Kaye Voyce Set Designer: Caleb Wertenbaker; Lighting Designer: Peter West. product_id=Above: Gregg Baker (Cinque) and Fikile Mvinjelwa (Antonio).All photos by WIlliam Struhrs courtesy of Spoleto Festival USA.

An Interview with Allen Anderson

His works have been recorded by such leading artists as the Lydian String Quartet, violinist Curtis Macomber, and pianist Aleck Karis. We spoke at his office in Hill Hall at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, on May 13, 2008.

TM: What was the musical environment like in your family? What were your beginnings as a musician?

AA: I have an older sister, who somewhere in our childhood decided she wanted to play the organ. It wasn’t the classical organ….

TM: Farfisa….

AA: It wasn’t a Farfisa. That would have been fun! This was the household chord-organ, where the left hand played full chords, and the right hand played the tune. That and an autoharp were the only musical instruments we had in the house, and it must have come when I was about twelve, perhaps ten or eleven.

I do have a compositional memory that precedes this by some unknown number of years. I probably was six or seven at the time. The whole family was in the automobile, I was sitting in the back seat — this was before the days of seat belts — and I remember distinctly moving forward to perch myself over the back of the front seat, and proclaiming to my parents that if they gave me any line of song lyrics, I would be able to sing back the song that went with these lyrics. “You mean a song you already know?” “No, just give me the lyrics, and I’ll sing the song!”

I remember being crushed by their response, because they thought this was impossible. They didn’t give me any lyrics, and I remember returning to the back seat, and not thinking of myself as a composer for many years.

My first conscious desire to want to be involved in playing an instrument like many people from my generation, males in particular, was after seeing the Beatles on Ed Sullivan. It must have been within a month after that we went out and got a guitar. I studied with a man who did jazz guitar, but I was interested in joining rock and roll bands. He was teaching me rather advanced music theory while he was trying to make me into essentially someone who could play background chords — not really a soloist, but someone who could comp the chords. That was my first exposure to music theory.

TM: Where were you growing up?

AA: In the San Francisco Bay area. I was born in Palo Alto, and grew up in Los Altos, right there. When all the San Francisco bands from Haight Ashbury hit, I was a little young, but I knew what their sound was, and started imitating that in the bands that I played in.

When George Harrison started playing the sitar, I became interested in Indian music as well, and for two years I studied sitar during the summers in Berkeley, with a real honest-to-goodness Indian master, sitting on the floor for four hours every morning, playing scales up and down the sitar. When I got to college at Berkeley I realized within a month or so that I would have to give up the guitar, because in those days the electric guitar was not an acceptable instrument — nobody paid attention to it in that environment. And there was no place for sitar, so I decided that I needed to learn how to play the piano.

TM: What year was this?

AA: I started in the fall of 1969.

TM: What was music at UCB like in the early seventies?

AA: Not being a performer of a classical instrument with any capability, it was interesting how composition got started for me. I was in a class in which every student was asked to perform, and my fellow classmates got up and played the viola, or the piano, and the only way for me to do the assignment was for me to have written the piece myself, so that I could find a way to perform. At the same time I realized that I could sing, and was attracted to the choirs available at the department, which I found very stimulating. Some of my strongest memories of those years are performing new music as a singer. They had commissioned Roger Sessions to write a cantata, and I was involved in the premiere of that as a member of the chorus – When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloomed — big full-length cantata, forty-five minutes or so, as I recall. A cappella Schoenberg – De Profundis — difficult, but I was loving it. Various kinds of pick-up groups, since those were the years of Vietnam, strikes, there would be a sudden convocation. There was one where in a few days we had to learn music that had been written for us to sing. There were a lot of things going on, but my memories are primarily of new music events.

TM: Early music in the seventies was also outside the mainstream. Was there an important early music scene going on?

AA: Philip Brett was on the faculty then, someone that people know for his interest in British early music and gay studies. I sang a number of early music concerts with his group in those days. There were musicology students who would get groups together to sing Josquin…

TM: To go back to your rock and roll roots for a moment, what sort of rock were you doing before getting to Berkeley?

AA: When we started we were covering California surf bands, and then it got into the British bands. I remember learning lots of Yardbirds and Zombies, and from California, the Byrds. When we started to do our own stuff it was derivative of San Francisco, something like the Jefferson Airplane.

TM: Did this music end up being integrated into your approach to composition?

AA: I don’t know where it is. To me, not only was the electric guitar put away in a case, and left at my mother’s house, and not found again for twenty years, but the music associated with it was also pushed aside. I do have memories of walking out of the music building at Berkeley and hearing rock bands playing from a quarter-mile away, and thinking “that sounds great!” Once or twice I went to some venue at night. I remember sitting up close and seeing Jerry Garcia playing in New Riders of the Purple Sage, not much farther from him than you and I are now, but by and large it was just something that I didn’t pay much attention. You couldn’t avoid it, being in a large college town –you hear the music, you live in a dormitory, and it’s playing down the hallway — but I wasn’t doing anything with it, and since I was trying to learn to write music pretty much on my own, I was looking at scores of the European avant-garde, and trying to emulate that.

TM: What were the composers that had an effect on your hearing in the seventies? My friends and I made a point of hearing the most avant-garde things we could — Sessions piano sonatas, and so on, and the Ives revival was going on.

AA: Ives was big in California too. I remember getting Ives piano music as a Christmas present, and loving it. Somewhere along the line I heard the Rite of Spring, and the Berg Violin Concerto, and of all things getting a recording of the Schoenberg Woodwind Quintet, a rather severe piece by comparison. One thing that really enthused me was seeing — I can’t imagine this now — Pierre Boulez on television — he must have been conducting Marteau — and thinking what a fabulous world of sound this was.

At Berkeley, as a student, there was a fair amount of new music. I remember hearing a concert performance of Le Marteau there too. The most important composer as a role model, someone I wanted to emulate, was when then-young Fred Lerdahl was on the faculty at Berkeley for a few brief years. Hearing him conduct a couple of his pieces, particularly one called Wake — I remember being blown away by it. Also, because of the proximity to Mills College there was a staunch avant-garde side in the Bay area. There was a Cage happening on the Berkeley campus, which must have been trying to duplicate the Black Mountain Happening. People on ladders stringing Christmas tree lights, a giant balloon that was inflated and tossed into the audience, batted around like at a baseball game…wild, madcap happenings.

I remember a big Antheil concert with someone in tuxedo but no shoes….I don’t remember any of the early minimalist composers. There was a performance of Merce Cunningham where Cage came out and sat down in a chair, took a bottle of champagne out of a cooler, poured it very deliberately….takes a sip, opens one of his books, starts reading…meanwhile the dance had been going on for ten minutes.

TM: We look back at the seventies and think “what a revolutionary period!”, but inside the academic walls it was as conservative as could be imagined.

AA: I had traditional harmony and counterpoint classes with Andrew Imbrie. We had to write tonal fugues in the style of Bach. I just ate that stuff up. I didn’t actually study composition with anybody as an undergraduate — I felt insecure about my abilities. The content of the courses was very traditional, and the education probably had a greater impact on my development than the avant-garde things mentioned earlier.

TM: Where did you go after Berkeley?

AA: I went to Brandeis University in Waltham, Massachusetts. One of my teachers had said “there is this professor you would probably get along with”, Seymour Shifrin, who had been a faculty member at Berkeley, but had left before I was an undergraduate there. I applied, and amazed, now, that I got in, because there were so few pieces that I had to send with the application. I ended up getting a PhD, and taught there for many years as well.

TM: Those who know the Boston scene may know Shifrin, but perhaps he is not generally well-known elsewhere.

AA: It’s true, he’s not. His music has disappeared since he died in 1979. He was a very high-minded fellow. There was a purpose to everything. I am talking about one’s commitment to writing music, his own, and what he expected of his students. Extremely serious. Everything was questioned; nothing could be put down on a page without full commitment to it and its significance. Nothing was automatic. For some people this was a difficult environment — they weren’t used to thinking this closely about everything. I wasn’t a particular fast composer, so I didn’t find it inhibiting. His standards were very high. I didn’t study with him my first year at Brandeis. I remember showing him the piece that I wrote. I was very proud of it — it was the longest thing I had ever written.

His response was “Well…you use the same type of phrase shaping”. He was probably right, but it wasn’t what I wanted to hear at that moment.

One of the features of his music that had a profound impact on me for a long time was that there was very little repetition. Again, everything had to be discovered, nothing could automatically come back. There were things that repeated, but almost in a covert way — they weren’t obvious returns. It had an effect on the way I heard, or even on my ability to hear certain things in pieces of music. I emulated it, I wanted to be like that, and for a long time my music had very little repetition, either local or large-scale.

TM: Is this stripping-down to the most basic expressive gesture, without using repetition to build a form, something that comes from serialism?

AA: Shifrin was not a serial composer. He was not a pianist, but would write his music at the piano, and my sense was that he was always hunting for what the next pitch would be. Not that he couldn’t project shapes, he certainly could. There is more repetition in Schoenberg than there is in Shifrin. As you say, he would whittle it to down to the essential thing that has to be said next. You listen to Shifrin’s music and you would think from my description that it would be a few sparse notes. It’s not that at all. It’s almost as if you have headed out into the jungle, and there is more underbrush than you could ever possibly imagine. A piece that I loved was Satires of Circumstance, with these elaborate, melismatic instrumental lines, spinning out numbers of notes — they are very elegant lines. And you think what was he talking about, about paring it down — you didn’t have to pare it down, you just had to know that every note was the important one at that moment, what it meant, and what its purpose was.

TM: Do you recall some of the things he was working on at the time?

AA: A piano piece, Responses. I heard Robert Helps premiere the piece at Carnegie Recital Hall, at a concert that Shifrin himself couldn’t attend, probably for health reasons already. The fifth string quartet…one of his last pieces, In the Nick of Time, commissioned by Speculum Musicae. I remember copying some of the parts for that, if I am not mistaken. A piece for early music instruments, A Renaissance Garland, with recorder, lute, viol, and a singer.

TM: It seems that this influence of “paring-down” from Shifrin is something that continues in your work until today.

AA: That is true. I have made a conscious effort to put things in my music that he didn’t have in his. There have been pieces where I tell people “believe it or not, this piece is an effort to bring in repetition in one way or another”. A piece which I wrote in 1996, Cloud Collar, where this was one of my goals in writing it. There are some small chordal formations which are arpeggiated and repeated — it seems like such a simple thing, a basic thing that music has done for centuries in one form or another, whether it’s accompanimental parts in Mozart, or more recently, in flamboyant manner, in minimalist repetition, but for me I had to struggle with my hand every time I wanted to repeat a note, or have a chord repeat. The other hand was trying to bat it away. Someone listening casually might think that repetition wasn’t a particularly important part of this music, yet for me it was a major breakthrough that I was able to include it in any way at all.

An element of compositional naiveté on my part is insisting for years in finding ways to not repeat some basic material. It’s a hard-fought battle for me to make myself really think of thematic shapes, thematic contents, that reusing them is not only a means to make compositions grow, but makes them audible in a way that is remarkable when you actually do it. I am laughing as I am saying this — these are basic and obvious things, but they were hard fought on my part, to get them in there.

With respect to Shifrin, I certainly still revere him as a person, and admire the music, but there had to be a conscious break for me to try some things on my own.

TM: The lack of repetition is the antithesis of popular.

AA: I try to place the music I write in some other listening place than the easy one. It’s demanding on the listener, and demanding on the performers as well. I want the experience of listening to it to be a different kind of experience than the one that might lead to dance….that’s not to say that elements of dance in a potentially more refined form aren’t things that I want…elegance, grace of motion, I certainly aspire to those things. The concert hall experience for my music that I want …it wouldn’t be right to call it meditation, but there’s an element of thought…not only a physical response, as important as that is.

TM: Were there other important figures in your study at Brandeis?

AA: I studied with Marty Boykan during my first year in graduate school. I hadn’t had much formal compositional training, so it was my first extended experience showing music to someone as I was writing it, and getting feedback. Marty was and remains the most profound musical thinker that I have encountered — he always has the best insights, the best references to examples of a similar problem from the great works of the classical music literature — how Beethoven handled this problem, or how Brahms couldn’t manage to get something similar to work. The depth and delicacy of his understanding of his music had a profound effect on me.

TM: Let’s talk about some of the pieces which have been recorded on CRI. Was the String Quartet written for the Lydian Quartet?

AA: Not exactly …. the Lydians recorded it. It’s a three-movement piece, and the middle movement was written first. This was when I was living in Boston, and the middle movement was written as a wedding present for two people who are here on the faculty at UNC…

TM: whose initials are in the title…

AA: “Variations on S.K. and R.L”, who are now my colleagues and good friends of mine, Susan Klebanow and Richard Luby. Susan Klebanow is the choral director and Richard Luby is a violinist.

TM: Susan was at Brandeis.

AA: She was at Brandeis when I was a graduate student and she was an undergraduate. She, my wife, and I all sang in early music groups together at Brandeis. That middle movement was based on the spelling out of their names in musical notation, and in the variations I tried to capture some element, some form of music that we shared, so there’s some very loosely shaped references to madrigals, an effort to get some baroquish string writing in there, because at the time Richard was playing a lot of baroque violin. There’s an attempt to capture the sound of Broadway show tunes….all this in a style that is never any of these things overtly. After that was written, and I had it played by the Lydian Quartet at Brandeis, I thought that maybe there could be a whole quartet built around this.

Not long after that I lost my job at Brandeis — didn’t get tenure there, and the first movement was written in a kind of defiant “I’ll show ‘em” anger at the forces that be…

the first movement is rather turbulent, and alternates between a vigorous music and one that is more resigned, with the resignation winning out at the end. The third movement is a sort of rondo.

TM: One of the things that struck me was how it drifts away at the end.

AA: I had a long-standing reluctance to end anything with a clear, forceful affirmation. It has happened in some more recent pieces, but there was a period of time in which that was about the only way that I could figure out how to get a piece to end, to have it trail off in one way or another.

TM: Could you talk about Casting Ecstatic?

AA: The Lydians had recorded the string quartet, and after the recording session Dan Stepner, the first violinist, said in exchange for having recorded this piece for you, I want you to write me a solo violin piece as a sort of payment. A win-win situation….I wrote Casting Ecstatic for Dan, and thought of it as a sort of concert etude for violin. There are a number of tricks in it that are devices that I was interested in exploring — it’s not an etude in the most concentrated, single-minded sense. Among the things that show up in that piece are efforts to have the violinist refinger the same pitch in close succession in order to avail himself of fingerings for other notes around it, as well as a sort of tremolo between a normally-stopped note and a harmonic in the same place on the finger board. This latter is the thing which I was referring to in the title, the “ecstaticness” of a note that suddenly takes off, and almost loses control under the finger of the player. That was one of the grounding elements.

TM: How was the move from the contemporary music in Boston to UNC?

AA: After teaching at Brandeis, I taught for two years at Columbia, and commuted back and forth between Boston and New York. When the possibility came for a permanent job, I moved to North Carolina. There are good people in contemporary music in North Carolina. There has always been activity at Duke and at Chapel Hill. Chapel Hill has added a director for the arts, Emil Kang, who wants to make Chapel Hill a real center for new music. I keep busy….

TM: You have a recent set of pieces for saxophone quartet. They seem to be a little more transparent in style, maybe drawing on the French wind tradition, with more repetition.

AA: That piece is from 2000-2001, and the repetition has become more of the language of that piece. One of the reasons that it happens in the saxophone collection is that it is the first piece in which I entered it into notation software as I was writing it, rather than writing it on paper, and then transferring it. Although it’s not always a good idea, I was pushing the replay button, and listening to how the computer performed it, and I would say that it was due to the software that the repetition became so pervasive in that composition.

It’s a curious set — a quartet in three movements, like the string quartet, but in this case, it’s the last movement which is the most important — it is as long itself as the other two combined. The first movement is just a table-setter — short, with a clear, straightforward shape to it, building by increments, with an ebb and flow, two-thirds of the way through it has its highest point, and falls off to the end. The second movement is almost entirely cantabile, based on sustained lines in one instrument or the other, and stems from my memory of a piece by Peter Maxwell Davies that goes back to when I was an undergraduate, one I liked very much, the Leopardi Fragments. I was sitting at my piano, not at the computer, thinking about what to do, and found myself playing something that was like the beginning of that Maxwell Davies piece, and not really getting it right, but using it as the opening. We’re talking about two measures worth of material, and you can see that I didn’t get I quite right, so I say in the score “after a misremembered measure or so of Peter Maxwell Davies”.

The third movement has been performed by itself, and works by itself without the other two, although I prefer it to be in their company. Some things I like are where all the parts get going, and it gets a kind of groove. There’s not an obvious repetition to it, but the momentum builds nicely.

TM: Your commission for the UNC chorus is quite different in style from your other works.

AA: When I came to UNC, Susan Klebanow asked me if I would write a piece for her chamber singers. I wrote a piece for piano and small choir to a text of Denise Levertov, and that was the first choral thing I had written in a long time. The piece you are referring to I wrote just over a year ago. Two years ago, the chair of the music department asked me, at the completion of the graduation ceremony, to write a piece for the graduation ceremony in the music department. I had no idea how to handle that – the music that I had written just didn’t lend itself to a commemorative, ceremonial function, and I had no idea how to fulfill the request. I put it aside for nine months.

In a composition class one of my students showed me a song that he was working on, and it seemed like he didn’t go very far in developing his material. So I wanted to rewrite it to show him how it could go. It turned out to be an inspiration to myself to write a choral piece. The next thing I had to have was a text. What kind of text do you use at college graduation ceremony? I ended up finding a translation of a Li Po poem.

The nature of its language is because it was for a graduation ceremony. A year ago it was premiered, not only by the graduating students, but by all their relatives in the audience.

We had 250 scores, and they all sightread it…it was performed again at the graduation ceremony last weekend, but this time by a small choir.

TM: Can you tell me about current projects?

AA: About two years ago, my colleague here at UNC, flutist Brooks de Wetter Smith, asked if I wanted to work on a collaborative project. He was going to Antarctica, planned to take photographs, and wanted to know if there was some way we could make something with sound and light when he got back. He took over 4000 photographs, and when he came back we went through them. I can’t say I looked at all 4000…but we assembled a number of photographs that would offer some cohesion. I wrote a score for that, which was just performed two weeks ago. That was the Iceblink project, for flute, clarinet, percussion, harp, violin, viola, cello, double bass, soprano and narrator — live music while the photographs were projected – not IMAX, but large all the same. It was interesting to work on. I was forced to complete every step as I went along, instead of blocking out the whole in any way. While I was writing, Brooks was feeding the photographs into a program to time them to the music. He needed to know exactly how long things would be to do it, so I had to work from the beginning straight through to the end, with very little revision time. As a result I wrote thirty-five minutes of music in seven months, which is much faster than I am used to writing.

It was exhausting, so I can’t say much about the next one, except that it will involve both professional and student performers.

[Click here for an excerpt from Held In the Weave]

image=http://www.operatoday.com/AllenAnderson.png image_description=Allen Anderson product=yes product_title=An Interview with Allen Anderson product_by=Above: Allen AndersonMay 27, 2008

Books 'n Things

Opera guide books tend to be a bit stuffy and boring, if indispensable. One of the best, first issued in 1961, has just been updated and reissued in a handsome softback from Amadeus Press.

It is “The Opera Companion,” a 693-page, good-quality paperback by the noted writer George Martin (a great bargain at $19.95). I cannot recommend this engaging book too highly; in fact, if my library had to be restricted to one book on opera, this would likely be it. Martin’s edition is of singular design and organization. It consists of three major sections, The Casual Operagoer’s Guide, a discursive consideration of many topics in opera – pitch, the opera orchestra, history of the art form, the nature of melody – and numerous others in a short, intelligent and pithy mode.

The second section is a dictionary-glossary of operatic and musical terms, while the third section of Martin’s “Opera Companion” is a quite detailed discussion of all aspects of forty-seven popular operas, from plot to musical analysis. Martin’s accounts are so reasonable and well-informed, I wish the number of operas treated were much larger. But he has chosen those most often heard by today’s audiences, and in spite of my own sixty-years of attending opera, I actually learned some new things about Gounod’s Faust, for example, and Mozart’s Così fan tutte from Martin.

In a time when that Mozart opera is foolishly treated by musicologists, who find in Così deep and dark contradictions or profound psychological themes, Martin’s clear-headed intelligent exposition of the music and text is exactly what’s called for; he understands the opera and its style and how it should be played. After reading Martin, you will too! His treatment of Faust as a melodic operetta rather than deep grand opera is exactly right; I recommend it and the entire book without reservation.

* * * * *

Put your hand up if you want to read a new tenor biography! Ummm....not very many hands. I don’t blame you, they can be a self-aggrandizing bore; most singer bios are. An exception was the Jussi Bjoerling book of a few years ago, in which his truthful wife spoke out with refreshing candor. Another exception is the new (2008) Amadeus Press biography of the greatest Italian tenor of my lifetime, the golden Franco Corelli. In terms of vocal power, color, quality and effectiveness, the Corelli tenor voice eclipsed all others; in terms of a balanced lifestyle, the poor man suffered greatly from all kinds of personal demons, stage fright and tenor-mania.

Holland-based René Seghers has written “Franco Corelli: Prince of Tenors,” a beautifully printed and illustrated book, that thrives because of excellent research, interviewing, and a strong narrative style. I picked up this book about 4 p.m. one day, and in just a few pages I was hooked – I read it all in one sitting, late into the night. I recommend starting earlier!

Seghers treats all aspects of Corelli’s history, from birth in Ancona on the Adriatic coast, to death in August 2003 in Milan, a demented and emaciated 84-y.o. millionaire, whose wife would not keep him at home for she feared his senile rages. The author, unlike many others, does not glamorize his subject, nor does he soften the rough edges of Loretta Di Lelio, Corelli’s possessive and controlling wife, who many believe made the “adolescent” tenor’s huge career possible. Loretta herself freely described her husband as immature and requiring constant care and attention. This she supplied in abundance, though in later years he somehow escaped her control and undertook some love affairs, which caused a temporary separation of the Corellis. This contrasts with hilarious scenes of the Corellis’ backstage rituals before performances, when the terrified tenor, insecure and superstitious, was sprinkled with holy water by Loretta, who would rub a crucifix on his throat just before she pushed him onto the stage. The Corelli anecdotes are legendary, as are his wars with opera managers, especially New York’s Rudolf Bing, and Seghers gives them full treatment, even dispelling some (Franco did not bite Birgit Nilsson in the Boston Turandot).

Of greater interest is Seghers’ thorough discussion of the evolution of Corelli’s stunning vocal technique, which he worked on constantly throughout his career. In the 1960s, in his forties, he often was in Spain seeking to make his voice more fluid and lyric through studies with the great Italian tenor of a generation before, Giacomo Lauri-Volpe, who helped him significantly. Corelli’s finest vocal period was the mid and later-1960s, and he readily credited the coaching of the senior Italian tenor di forza.

Corelli’s major public career extended from about 1958 to 1975. The author organizes the greater part of his book chronologically, touching upon each season, where and what Corelli sang, and often with somea critical analysis. This required prodigious research, and Seghers’ account has the strong flavor of authenticity. In mid-career Corelli moved to New York City and lived there until old-age; this facilitated his many seasons of dominance at the Metropolitan Opera, where, along with Milan’s La Scala, the handsome Corelli established himself as the most vocally potent and popular Italian tenor of his era. “Prince of Tenors,” as a book, is a keeper; it is going on my shelf and I expect to take it down often. Among other virtues, author Seghers is an accomplished photographer and knows the value of visuals, so has furnished his 526-page book richly with photographs, many never seen before. The list price is a steep $34.95; Amazon is offering copies at $21.95. Amadeus Press and René Seghers have done the vocal world a service by publishing this invaluable biography of the wondrous Corelli.

* * * * *

Now, to the noted composer Dr. Paul Moravec. He is currently visiting professor at the Institute for Advanced Studies, Princeton, NJ, and is in addition a professor of music at Adelphi University. Thus, Moravec is an academic composer and distinguished musical scholar. His music, to my ear, sounds exactly that – “academic,” if highly competent.

I bring this up because in Season 2009 you’ll be hearing a lot more about Moravec, as his first-ever opera, “The Letter” (based on a 1927 play by Somerset Maugham, famous from the Bette Davis 1940 movie), is being premiered at Santa Fe Opera, starring Patricia Racette in the Davis role of a murderous wife.

I just listened several times to two Naxos recordings of Moravec’s

music, one, “Tempest Fantasy,” is a Pulitzer prize winner (Naxos 8.559323

), the other is “The Time Gallery” (Naxos 8.559267). Both are

interesting, and they share some traits. While the music lacks lyric line, it

is energetic -- busy and chattery (one friend called it “molecular”),

except when it makes a point to be quiet and mellow, which doesn’t last

very long, for its heart lies in smart antics and excitement, though these

particular selections are not much for originality or melodic effect.

I just listened several times to two Naxos recordings of Moravec’s

music, one, “Tempest Fantasy,” is a Pulitzer prize winner (Naxos 8.559323

), the other is “The Time Gallery” (Naxos 8.559267). Both are

interesting, and they share some traits. While the music lacks lyric line, it

is energetic -- busy and chattery (one friend called it “molecular”),

except when it makes a point to be quiet and mellow, which doesn’t last

very long, for its heart lies in smart antics and excitement, though these

particular selections are not much for originality or melodic effect.  There

is a lot more to this composer than these two CDs, and I wont comment more

because I have not heard his lyric writing. But considering that opera, even

“opera noir,” as Santa Fe is calling the forthcoming show, must be about

singing and lyric reach – if that does not occur, rather than true opera,

you have a play with music. While a novice opera composer, Moravec is an

accomplished and sophisticated man; and his text collaborator, the jazz

critic Terry Teachout, is a bright one too. So they may come up with a good

show; how “operatic” it will be remains to be seen. We hear it’s

90-minutes in length, with an orchestral interlude. Bette Davis is a hard act

to follow, but maybe clever Santa Fe can pull it off. The talented

singing-actress soprano Racette is clearly an asset; she was recently

reported advising the composition team on how to make their ending more

dramatic. Will this be opera by committee?

There

is a lot more to this composer than these two CDs, and I wont comment more

because I have not heard his lyric writing. But considering that opera, even

“opera noir,” as Santa Fe is calling the forthcoming show, must be about

singing and lyric reach – if that does not occur, rather than true opera,

you have a play with music. While a novice opera composer, Moravec is an

accomplished and sophisticated man; and his text collaborator, the jazz

critic Terry Teachout, is a bright one too. So they may come up with a good

show; how “operatic” it will be remains to be seen. We hear it’s

90-minutes in length, with an orchestral interlude. Bette Davis is a hard act

to follow, but maybe clever Santa Fe can pull it off. The talented

singing-actress soprano Racette is clearly an asset; she was recently

reported advising the composition team on how to make their ending more

dramatic. Will this be opera by committee?

J. A. Van Sant © 2008

image=http://www.operatoday.com/opera_companion.png image_description=The Opera Companion product=yes product_title=George Martin: The Opera Companion product_by=Amadeus Press, 2008 product_id=ISBN-13: 978-1574671681 price=$15.56 product_url=http://www.amazon.com/dp/1574671685?tag=operatoday-20&camp=14573&creative=327641&linkCode=as1&creativeASIN=1574671685&adid=0N216JRW06R8V3ATR3PC&Burly and Savage, but Elegant: Met Orchestra at Carnegie Hall

By JAY NORDLINGER [NY Sun, 27 May 2008]

By JAY NORDLINGER [NY Sun, 27 May 2008]

The Metropolitan Opera season is over, and so is the Met Orchestra season: Last week, that extraordinary band gave a final concert in Carnegie Hall. They are an opera orchestra that plays like an orchestra orchestra — a top-flight one.

Opera Meets Animation to Tell a Chinese Tale

By DANIEL J. WAKIN [NY Times, 26 May 2008]

By DANIEL J. WAKIN [NY Times, 26 May 2008]

CHARLESTON, S.C. — The opening scene is a vast cartoon, projected on a scrim, with viewers zooming past clouds and mountain peaks to an egg, which falls, bursts and gives birth to Monkey. The scrim goes up, and the cartoon dissolves into a stage full of flipping acrobats, a monkey tribe flying from bamboo pole to bamboo pole. The score pulsates with an electronic beat.

[Click here for official web site.]

Die Bassariden, Bayerische Staatsoper, Munich

By George Loomis [Financial Times, 26 May 2008]

By George Loomis [Financial Times, 26 May 2008]

Alarmed by the threat of Dionysian rites in his kingdom, Pentheus, the ill-fated king of Thebes, personally investigates in disguise. In Christof Loy’s tense new production of Hans Werner Henze’s The Bassarids for the Bayerische Staatsoper, Pentheus finds himself centre-stage amid the cultish practices, women lined up on one side of him, men on the other.

Eugene Onegin, Glyndebourne Festival, UK

By Andrew Clark [Financial Times, 25 May 2008]

By Andrew Clark [Financial Times, 25 May 2008]

Love – as we know from countless operas if not from personal experience – is a complicated thing. Two people can have the same intense feeling, but not at the same time or in circumstances that deny fulfilment.

Argentine gem will miss its 100th birthday party

BY TAOS TURNER [Miami Herald, 25 May 2008]

BY TAOS TURNER [Miami Herald, 25 May 2008]

It's enough to make the great Caruso weep.

Today, on its 100th birthday, the Teatro Colón, this city's cultural jewel and one of the world's most majestic opera houses, is closed and on the verge of disintegration, a victim of the ravages of politics, incompetence and time.

Merry Widow at ENO

However that is exactly what John Copley’s straightforward, pretty and — heaven forfend! - traditional staging of 'The Merry Widow' has to offer. Set around the time of the opera’s composition, the production has chocolate-box frocks, dashing uniformed officers, a full-blown 'Pontevedro in Paris' at Hanna’s home (complete with folk-dancers) and orange-flounced can-can girls at Maxim’s.

In the title role, Amanda Roocroft at first seemed rather matronly and ill at ease — perhaps her first-act costume was partly to blame — but came into her own from the second act onwards when she brought out Hanna’s wit, warmth and down-to-earth charm. Vocally there was a touch of strain in her top notes, and she was happier in the middle register, floating a beautiful Vilja-Lied.

Philip O'Brien, the second-cast Danilo, was making his company début at this performance, and like Roocroft he took a while to make something of his character. He grew in presence throughout the performance, and by the time he made his exit to Maxim’s at the end of Act 2 his charisma was sufficient to hold the audience’s sympathy.

When they finally got together, unfortunately, it lacked both credibility and passion - the connection between them was simply inadequate. Fortunately, Alfie Boe’s Camille was full of youthful ardour towards Fiona Murphy’s beautiful, vivacious Valencienne; these two were really the production’s life force, as engaging to watch as to hear.

Jeremy Sams’s clever (and sometimes very risqué) translation did not always come across clearly in the sung numbers. It was put to best effect in the spoken dialogue and the comic numbers, providing ample material for Richard Suart’s Baron Zeta and (especially) Roy Hudd’s endearing Njegus. Both are mainly speaking roles, though the biggest hit of the evening was Hudd’s showpiece number in Act 3. Daniel Hoadley (St Brioche) and Hal Cazalet (Cascada) provided an almost slapstick angle to the coomedy, sporting ludicrous “French” accents.

Oliver von Dohnanyi’s conducting seemed to revel in the rumbustious numbers but was almost leaden in the quicker, lighter passages, ill-serving the energetic choreography by Anthony Van Laast and Nichola Treherne.

Amanda Roocroft (Hanna Glawari)

Amanda Roocroft (Hanna Glawari)

Though it had its flaws, this was a highly entertaining evening, and the audience emerged from the theatre with a spring in its step. It was just a shame the house was not fuller: as classic operetta tends to pull in a substantially different audience from most of ENO’s fare, it is perhaps an audience that isn't used to paying ENO’s ticket prices, once on a par with other West End shows but nowadays substantially higher.

*****

As I had wanted very much to hear John Graham-Hall as Danilo, and had not been aware when booking that he was not due to appear on May 6th, I decided to return a few nights later in order to hear him. Although the role lies rather low for him, it surprisingly seems to fit him like a glove in other respects. Who would have thought this tall, pale-faced tenor — normally at home in 'character' roles — could be so rakishly attractive as the awkward playboy? And his chemistry with Roocroft was really touching.

Richard Suart (Baron Zeta) & John Graham-Hall (Count Danilo Danilowitsch)

Richard Suart (Baron Zeta) & John Graham-Hall (Count Danilo Danilowitsch)

Ruth Elleson © 2008

image=http://www.operatoday.com/080423_0040widow.png image_description=Fiona Murphy (Valencienne) & Alfie Boe (Camille de Rosillon) [Photo: Clive Barda courtesy of English National Opera] product=yes product_title=Franz Lehár: Die lustige Witwe (The Merry Widow) product_by=Hanna Glawari, The Merry Widow (Amanda Roocroft); Camille de Rosillon (Alfie Boe); Njegus (Roy Hudd); Baron Zeta (Richard Suart); Danilo (John Graham Hall); Valencienne (Fiona Murphy). Director: John Copley. Set Designer: Tim Reed. English National Opera. product_id=Above: Fiona Murphy (Valencienne) & Alfie Boe (Camille de Rosillon)All photos by Clive Barda courtesy of English National Opera.

Masterpiece Masterfully Rendered in Toronto

Having run into a local friend unexpectedly at intermission, and having related the above information, he hurriedly said, “ohhhhhhh, you should come back sometime for a real opera.”

Judging from intermission comments recently in Toronto, and some empty seats for part two, the piece apparently remains caviar for the gourmand, rather than bread and butter for the masses. I am hard pressed to quite understand why, especially when the work is treated to such a world class performance as mounted here by Canadian Opera Company.

Dany Lyne’s gorgeous design — ethereal, timeless and haunting — provided the perfect backdrop and playing environment for Debussy’s masterpiece. While the basic construction featured a girdered bridge which elevated actors about ten feet off the stage floor, visual variety was introduced through the addition of well-chosen set pieces (throne, bed, rickshaw, etc.), and the revelation of fold out features such as a hidden stairway and door leading from above to the “depths” of the debris-strewn floor in which “Pelleas” dwelt during much of the first act.

The stage left third of the structure was able to be raised and lowered, creating “Melisande’s” bedroom tower, a beautiful evocation of a depth to the well, and a final descent to the grave for our heroine’s remains, even while her spirit (in the form of a diaphanous bed canopy) ascended to the heavens.

Scrims, opaque spun fiberglass drops, and a cyclorama fronted by expressive filigreed tree branches, were inventively lit by Thomas C. Hase with his perfectly judged special effects and a highly creative design. He was assisted by John Prautschy. A glowing blue moon, passing torchlight, silhouette imagery, the up-lit fountain, and the down lit bed and stairs were among the superbly calculated effects. A passionate orb of a sun called to mind Stephen Crane’s “the red sun was pasted in the sky like a wafer.”

Ms. Lyne’s vibrant Asian-influenced costumes could also hardly have been bettered, and the choice to put “Melisande” in vivid reds proved to be inspired, completely playing against the usual wispy “type” for this mysterious character. Indeed, our heroine’s first appearance behind a scrim, in a rich Chinese red dress with an impossibly long train, and draped in an over-sized off-white veil was a triumph of character statement, making her at once irresistibly alluring and impossibly indefinite. The minute attention to each and every technical detail created true theatrical magic.

(l – r) Alain Coulombe as the Doctor, Barbara Dever as Geneviève (behind Golaud), Pavlo Hunka as Golaud, Isabel Bayrakdarian as Mélisande and Richard Wiegold as Arkel

(l – r) Alain Coulombe as the Doctor, Barbara Dever as Geneviève (behind Golaud), Pavlo Hunka as Golaud, Isabel Bayrakdarian as Mélisande and Richard Wiegold as Arkel

Such a top notch design would go for nothing, of course, without a cast up to the musical challenges, and COC came up with winners all around. At any given period there is always a dream team for the title roles, and on the basis of this visit, I would have to say the mantle has been passed to stars Russell Braun and Isabel Bayrakdarian, Canadians both. Although Mr. Braun has more experience with his well-known “Pelleas” (including a memorable Robert Wilson version in Salzburg with Dawn Upshaw), there is nothing in these fearsomely demanding roles that eludes either one of these superb interpreters.

Ms. Bayrakdarian offered a most compelling take on “Melisande” with a bit more starch than some. She displayed a wonderful technique, an even production, fine projection with a pleasing point to the tone, and thorough attention to each quicksilver shift of mood and subtext. Mr. Braun now pretty much owns his role, and he negotiates “Pelleas’“ highest reaches with seasoned perfection, singing with a robust and responsive baritone that has mastered every nuance of his tortured attraction to his brother’s wife.

Pavlo Hunka’s compelling “Golaud” was every inch the powerful linchpin central to the drama, as it needs to be. He managed more variety than other interpreters that I have seen, and his obsession with finding confirmation of the betraying physical act was well-balanced between heartsick introspection and macho bluster.

Russell Braun as Pelléas and Isabel Bayrakdarian as Mélisande

Russell Braun as Pelléas and Isabel Bayrakdarian as Mélisande

Richard Wiegold used his dark imposing bass to etch an unusually detailed portrait of “Arkel,” and he was well rewarded at curtain call for his efforts. Barbara Dever offered dramatic power and a steady outpouring of her rich mezzo for a fine assumption of “Genevieve.” The small role of the “Physician” was fleshed out with wonderful stage business, and the few rolling phrases required were well intoned by Alain Coulombe.” Only Erin Fisher’s attractive if light-voiced “Yniold” seemed one size too small to ride the occasional dense orchestrations.

Director Nicholas Muni made masterful use of every playing space and level available to him; he created memorable, chills-inducing stage pictures and groupings through well-motivated blocking; and he could give a masters class on effective character development and interaction. My God, here is a director who not only understands the work, but serves it! Let’s hope his creative philosophy starts an epidemic in the opera world. For this is decidedly a brilliant mounting of Debussy’s “Pelleas,” rather than Muni’s. Would that all directors “got” that difference.

The superb playing from the pit was diligently led by Jan Latham-Koenig. The acoustic of the house seemed very grateful to this impressionist work, even if I did think that it favored the orchestra slightly more than the singers. This richly detailed reading not only had the wispy, blurry succession of solo lines flawlessly interwoven, but the blocks of woodwinds, strings, and horns were individually and collectively well-knit into a clean ensemble. The passionate outbursts were all the more effective for the placid churnings that came before, and the inner life and forward thrust of the rhythmic pulse was never lost.

The beautiful “new” house in the Four Seasons Center would be an architectural pride of any world city, and it is perfectly complemented on stage by a stunning “Pelleas et Melisande” that makes the best possible case for this elusive work. Will this opus ever become a bread-and-butter opera? Perhaps not.

But for those of us who occasionally relish the highest quality caviar on our musical menu, this totally winning production was a very rich feast.

James Sohre © 2008

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Isabel_Bayrakdarian_Melisan.png image_description=Isabel Bayrakdarian as Mélisande (Photo: Michael Cooper) product=yes product_title=Claude Debussy: Pelléas et Mélisande product_by=Golaud, King Arkel’s grandson (Pavlo Hunka), Mélisande (Isabel Bayrakdarian), Geneviève, mother of Pelléas and Golaud (Barbara Dever), Arkel, King of Allemonde (Richard Wiegold), Pelléas, King Arkel’s grandson (Russell Braun), Yniold, Golaud’s son by his first marriage (Erin Fisher), The Doctor (Alain Coulombe). Conductor: Jan Latham-Koenig. Director: Nicholas Muni. Canadian Opera Company. product_id=Above: Isabel Bayrakdarian as MélisandeAll photos by Michael Cooper courtesy of Canadian Opera Company

May 25, 2008

MOZART: Le Nozze di Figaro — Vienna 2001

Music composed by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Libretto by Lorenzo Da Ponte after Beaumarchais’ play La folle journée, ou Le mariage de Figaro (1784).

First Performance: 1 May 1786, Burgtheater, Vienna.

| Principal Characters: | |

| Count Almaviva | Baritone |

| Countess Almaviva | Soprano |

| Susanna her maid, betrothed to Figaro | Soprano |

| Figaro valet to Count Almaviva | Bass |

| Cherubino the Count’s page | Mezzo-Soprano |

| Marcellina housekeeper to Bartolo | Soprano |

| Bartolo a doctor from Seville | Bass |

| Don Basilio music master | Tenor |

| Don Curzio magistrate | Tenor |

| Barbarina daughter of Antonio | Soprano |

| Antonio gardener, Susanna’s uncle | Bass |

Setting: Aguasfrescas near Seville, the Almavivas’ country house

Synopsis:

Act I

A half-furnished room in the castle of Count Almaviva

Figaro's satisfaction at the location of the room assigned to him and his prospective bride, Susanna, is shattered when she points out that the Count (who has done away with his hereditary right to the first night with any bride on his estate, but regrets it) has designs on her and the location of the room will assist him.

Marcellina plans to marry Figaro, who has signed a contract promising marriage if he is unable to repay money borrowed from her, and Bartolo is eager to be revenged on Figaro by assisting her. Cherubino tells Susanna that the Count is sending him away because of his amorous inclinations. He hides behind a chair as the Count approaches. Susanna tries to avoid the Count's advances. He hides behind the chair when Basilio appears, and Cherubino hides in the chair. Basilio warns Susanna that the Count will be angry if she encourages Cherubino and the Count emerges from hiding and discovers Cherubino. The Count accepts the praises of his servants, led by Figaro, but postpones the crowning of Susanna as a bride. He assigns Cherubino a place in his regiment and orders him to leave at once.

Act II

The Countess' bedroom

The Countess is sad because her husband neglects her. She joins in Figaro's scheme to disguise Cherubino as Susanna, who is to agree to an assignation with the Count, who can then be caught in the act. But the Count arrives unexpectedly. Cherubino hides, but betrays himself by knocking something over. The Count is ready to break down the door, but when he goes to get tools, Susanna lets Cherubino out and he jumps from the window, and she takes his place, surprising not only the Count, but the Countess, who takes her time about forgiving her husband for his suspicions.

Figaro comes in to announce that all is ready for the wedding, but is confronted by the Count, who knows it is Figaro who has written an anonymous letter telling him the Countess will be receiving a lover in the garden (part of Figaro's elaborate plot). Antonio, the gardener, arrives with the complaint that someone jumped from the window into his garden. When Figaro claims that it was he who jumped, Antonio produces a paper which dropped from Cherubino's pocket, challenging him to idenfity it. With the assistance of the women, he does so - it is the page's commission. Marcellina, supported by Bartolo and Basilio, arrives to press her claim for Figaro's hand, as he has no money to pay her back.

Act III

A big drawing room

Urged by the Countess, Susanna pretends to agree to an assignation with the Count, but he overhears her telling Figaro of the success of the plan.

Marcellina and Bartolo arrive with a lawyer to demand that Figaro fulfil his contract, but it is discovered that he is the long-lost son of Marcellina and Bartolo. Susanna boxes Figaro's ears when she sees him embracing Marcellina, but explanations prove satisfactory to all except the Count, who storms out.

The Countess laments her sad life with a faithless husband. She gets Susanna to write him a note agreeing to a meeting in the garden, sealing it with a pin which is to be returned as his answer. Peasant girls, including Barbarina, Antonio's daughter, and Cherubino, whom she has dressed as a girl to hide him from the Count, bring gifts to the Countess, but the Count and Antonio appear and unmask Cherubino. The Count is about to send Cherubino away, but Barbarina, reminding him of promises made when he was making advances to her, successfully asks for Cherubino as her husband.

There is a double wedding ceremony - Marcellina and Bartolo as well as Susanna and Figaro. Susanna slips her note to the Count. Figaro is amused to see him prick his finger with the pin, but does not realise the note is from Susanna.

Act IV

The garden, at night

Barbarina, entrusted with taking the pin to Susanna, has lost it, and Figaro learns that it was Susanna who wrote the note. The Countess is to take Susanna's place in meeting the Count, and they have changed clothes. Marcellina warns Susanna that Figaro is hiding, planning to trap her, and she sings an alluring love-song, intended for him, but which he interprets as being directed at the Count. Cherubino makes advances to the Countess, under the impression that she is Susanna. Susanna intends to be revenged on Figaro for doubting her, but he penetrates her disguise and turns the tables, pretending to believe she is really the Countess and making love to her. Explanations and reconciliation ensue and, realising that the Count is listening, they resume the apparent love scene between Figaro and the Countess. The Count summons everyone to witness his wife's disgrace, ignoring pleas for mercy. He is silenced when the Countess herself adds her plea and in turn asks her forgiveness, which she grants.

[Synopsis Source: Opera~Opera]

Click here for the complete liberetto.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Keenlyside_Count.png image_description=Il Conte di Almaviva: Simon Keenlyside audio=yes first_audio_name=W. A. Mozart: Le Nozze di Figaro first_audio_link=http://www.operatoday.com/Nozze2.m3u product=yes product_title=W. A. Mozart: Le Nozze di Figaro product_by=Il Conte di Almaviva: Simon KeenlysideLa Contessa di Almaviva: Melanie Diener

Susanna: Tatiana Lisnic

Figaro: Carlos Alvarez

Cherubino: Angelika Kirchschlager

Marcellina: Francesca Pedaci

Bartolo: Maurizio Moraro

Basilio: Michael Roider

Don Curzio: Peter Jelosits

Barbarina: Ileana Tonca

Antonio: Boaz Daniel

Chor der Wiener Staatsoper, Wiener Philharmoniker

Riccardo Muti (cond.)

Live Performance, 18 June 2001, Wiener Festwochen 2001, Theater an der Wien, Vienna

A Berlin Sampler

Granted, it may have been hard for any indoor performance to totally upstage the glorious early summer weather and delicious seasonal white asparagus entrees on offer in any number of attractive and pleasant outdoor eateries. But venture indoors I did. . .

Staatsoper unter den Linden offered a well-traveled production of “La Traviata” that was very long on concept and conversely short on just about everything else. The major exception was the wonderful playing from the orchestra under the baton of Dan Ettinger. Save for an inexplicably scrappy moment or two in Act Three (Flora’s party), the ensemble showed great presence and stylistic acumen, tempered by sensitive and subtle support of the soloists.

Would that stage director Peter Mussbach have had as much success with his vision of the piece as Violetta’s one woman show. Poor Elzbieta Szmytka started out floating toward us from far upstage as a ghostly apparition during the prelude and simply never left the stage the entire evening.

This opening moment indeed promised much. A black raked stage with two ramps escaping into the pit was dotted with interrupted receding white lines brought into great relief (along with our diva’s white strapless gown) with black light. A swirling, disorienting light show dissolved into a highly evocative over-sized video projection of rain on a window pane, an image that framed the entire stage. And then. . .

Nothing much happened. Okay, to be fair a shiny slit drape flew in upstage but then it remained there constantly through opera’s end. The chorus in the opening act sang from off stage until the farewell chorus when they dutifully filed on, and then off. Soloists paraded through, and down into the pit without relating to Violetta who alternately swooned to the floor, stood up again unsteadily, or mostly, stood and sang front.

Was this Violetta’s dying delusion? A video projection of a car going through a tunnel, and later, of many cars in heavy traffic proved to be a red herring, evoking thoughts of Princess Di’s untimely end without any other parallels drawn. It did clarify that the white marks on the stage were highway-like traffic lines on a “dramatic” highway to nowhere. . .

The stage was bare until Act Two when a single chair was placed down center. Then in Act Three (or the second scene of Act Two if you’re a purist) the chorus files on, each holding a chair. They first sit in rows, then rise indignantly after Alfredo throws the money at Violetta (well, in the air like confetti really), and then all, to a person, jump up and stand on the chairs like they have collectively seen a mouse. Where the “chair-mounting music” is in this score, I couldn’t tell you. Or maybe they suddenly realized they were playing in the “traffic,” which had returned to the video projector?

If there were some interesting ideas in the Violetta-Germont duet, there were also major miscalculations. After having begun routinely, it regressed into first a rather touching moment with Germont as a comforting substitute father, but then transgressed into a creepy sort of Daddy sexual encounter during which he put his hand a bit too far up her skirt for our comfort level.

Does it surprise you to learn that there was no bed in the final act, which began with the same ghostly promenade as at the beginning? As the stage lights got brighter, we discovered Alfredo asleep upstage on the floor. Asleep upstage! As he got up and stretched and yawned, it prompted me to wonder if this whole thing might have been meant to have been his dream. At least in the final duet, the characters related to each other, albeit only slightly.

While great vocalism might have injected interest, what we had on offer was merely “good.” The minor roles were certainly sung competently, with “Flora” quite beautifully voiced by Katherina Kammerloher.