June 30, 2008

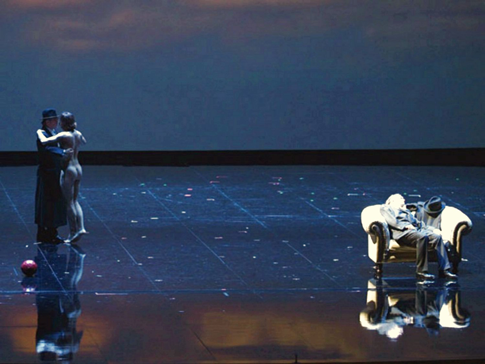

MOZART: Così fan tutte — Salzburg 2004

Music composed by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791). Libretto by Lorenzo Da Ponte.

First Performance: 26 January 1790, Burgtheater, Vienna.

| Principal Characters: | |

| Fiordiligi, a lady from Ferrara, living in Naples | Soprano |

| Dorabella, sister of Fiordiligi | Soprano |

| Guglielmo, an officer, Fiordiligi’s lover | Bass |

| Ferrando, an officer, Dorabella’s lover | Tenor |

| Despina, maidservant to the sisters | Soprano |

| Don Alfonso, an old philosopher | Bass |

Setting: 18th Century Naples

Synopsis:

Act I

It is early morning. Two young officers, Ferrando and Guglielmo, boast about the beauty and virtue of their sweethearts, the sisters Dorabella and Fiordiligi (“La mia Dorabella”). Don Alfonso, an older man and a friend of the two officers, insists that a woman's constancy is like the Arabian phoenix - everyone says it exists but no one has ever seen it (“È la fede delle femmine”). He proposes a wager of one hundred sequins that if they give him one day, and do everything he asks, he will prove the sisters are like all other women - fickle. The two young men willingly agree to Alfonso's terms and imagine with pleasure how they will spend their winnings (“Una bella serenata”).

Fiordiligi and Dorabella gaze blissfully at their miniature portraits of Guglielmo and Ferrando (“Ah, guarda sorella”), and imagine happily that they will soon be married. Alfonso's plan for the day begins when he arrives with terrible news: the young officers have been called away to their regiment. The two men appear, apparently heartbroken, and they all make elaborate farewells (“Sento, o dio”). As the soldiers leave, the two women and Alfonso wish them a safe journey (“Soave sia il vento”). Alfonso is delighted with his plot and feels certain of winning his wager.

As Despina complains about how much work she has to do around the house, Fiordiligi and Dorabella, upset by the departure of their fiancés, burst in. Dorabella vents her feelings (“Smanie implacabili”), but Despina's advice is to forget their old lovers with the help of new ones. All men are fickle, she says, and unworthy of a woman's fidelity (“In uomini, in soldati”). Her mistresses resent Despina's approach to love, and depart. Alfonso arrives to plan the next stage of his wager: he enlists Despina's help to introduce the girls to two exotic visitors, in fact Ferrando and Guglielmo in disguise, and is relieved when Despina does not recognize the two men. The sisters are scandalized to discover strange men in their house. The newcomers declare their admiration for the ladies, each wooing the other's girlfriend, according to Alfonso's design, but the girls reject them. Fiordiligi likens her constancy to a rock in a storm (“Come scoglio”). The men are confident of winning the bet, but Alfonso reminds them that the day is still young. Ferrando reiterates his passion for Dorabella (“Un'aura amorosa”), and the two go off to await Alfonso's further orders. Despina, still unaware of the men's identities, plans the afternoon with Alfonso.

As the sisters lament the absence of their lovers, the two “foreigners" stagger in, pretending to have poisoned themselves in despair over their rejection. The sisters call for Despina, who urges them to care for the men while she and Alfonso fetch a doctor. Despina re-enters disguised as a doctor and, with a special magnet, pretends to draw off the poison. She then demands that the girls nurse the patients as they recover. The men revive (“Dove son?”), and request kisses. As Fiordiligi and Dorabella waver under renewed protestations of love, the men begin to worry.

Act II

In the afternoon, Despina lectures her mistresses on their stubbornness and describes how a woman should handle men (“Una donna a quindici anni”). Dorabella is persuaded that there could be no harm in a little flirtation, and surprisingly, Fiordiligi agrees. They decide who will pair off with whom, and fitting perfectly into Alfonso's plan, each picks the other's original suitor (“Prenderò quel brunettino”).

Alfonso has arranged a romantic serenade for the sisters in the garden, and after delivering a short lesson in courtship, he and Despina leave the four young people together. Guglielmo, courting Dorabella, succeeds in replacing her portrait of Ferrando with a golden heart (“Il core vi dono”). Ferrando apparently has less luck with Fiordiligi (“Ah, lo veggio”); but when she is left alone, she guiltily admits he has touched her heart (“Per pietà”).

When they compare notes later, Ferrando is certain that they have won the wager. Guglielmo, although pleased at the report of Fiordiligi's faithfulness to him, is uncertain how to break the news of Dorabella's inconstancy to Ferrando. He shows his friend the portrait he took from Dorabella and Ferrando is furious. Guglielmo blames it all on women (“Donne mie, la fate a tanti!”), but his friend is not comforted (“Tradito, schernito”). Guglielmo asks Alfonso to pay him his half of the winnings, but Alfonso reminds him again that the day is not yet over.

Fiordiligi rebukes Dorabella for being fickle, but finally admits that in her heart she has succumbed to the stranger. Dorabella coaxes her to give way completely, saying love is a thief who rewards those who obey him and punishes all others (“È amore un ladroncello”). Left alone, Fiordiligi decides to run away and join Guglielmo at war, but Ferrando, pursuing the wager, tries one last time to seduce her and succeeds.

Guglielmo is furious, but Alfonso counsels forgiveness: that's the way women are, he claims, and a man who has been deceived can blame only himself (“Tutti accusan le donne”). As night falls, he promises to find a solution to their problems: he plans a double-wedding.

Despina runs in with a double-wedding plan of her own: the two sisters have agreed to marry the “foreigners,” and she is to find a notary for the ceremony. The scene is set for the marriage, and Alfonso arrives with the notary - Despina in another disguise. As Fiordiligi and Dorabella sign the contract, martial strains herald the return of the former lovers' regiment. In panic the two women hide their intended husbands and try to compose themselves for the arrival of Ferrando and Guglielmo. The two apparently joyful soldiers return, but soon become disturbed by the obvious discomfort of the ladies. When they discover the notary the sisters beg the two men to kill them. Ferrando and Guglielmo reveal to them the identities of the "foreigners.” Despina realizes that Alfonso had let her in on only half of the charade and tries to escape. Alfonso bids the lovers learn their lesson and, with a hymn to reason and enlightenment, the day comes to a close.

Commentary.

“Così has been seen as revealing a dark side to the Enlightenment, an anti-feminist sadism (Ford 1991). Yet by any showing the most admirable character is Fiordiligi. The girls develop more than the men. Dorabella at least learns to understand her own lightness; and ‘Fra gli amplessi’ suggests that Fiordiligi has matured through learning the power of sexuality. There is little sign that Guglielmo learns anything in the school for lovers, even that those who set traps deserve to get caught, although his vanity is wounded as deeply as his purse. Ferrando, however, comes to live as intensely as Fiordiligi, and may appear to have fallen in love with her. To suggest that they should marry (leaving Guglielmo for Dorabella) is, however, still less satisfactory than reversion to the original pairings. The conclusion represents not a solution but a way of bringing the action to a close with an artificiality so evident that no happy outcome can be predicted. The music creates this enigma, but cannot solve it.”

Julian Rushton: 'Così fan tutte', Grove Music Online (Accessed 11 June 2006).

Click here for complete libretto.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/cosi_salzburg_2004.png image_description=Cast of Così fan tutte, Salzburg 2004 (Photo: Bernd Uhlig) audio=yes first_audio_name=Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Così fan tutte first_audio_link=http://www.operatoday.com/Cosi2.m3u product=yes product_title=Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Così fan tutte product_by=Fiordiligi (Tamar Iveri)Dorabella (Elina Garanca)

Despina (Helen Donath)

Ferrando (Saimir Pirgu)

Guglielmo (Nicola Ulivieri)

Don Alfonso (Thomas Allen).

Wiener Philharmoniker, Wiener Staatsopernchor, Philippe Jordan (cond.).

Live performance, 30 July 2004, Großes Festspielhaus, Salzburg

June 23, 2008

Aldeburgh Festival, Snape Maltings, Suffolk

By Martin Hoyle [Financial Times, 23 June 2008]

By Martin Hoyle [Financial Times, 23 June 2008]

Last Thursday György Kurtág and his wife Márta played pieces from his piano collection Játékok on the sonically upholstered upright with its almost woolly sound now favoured by the composer, making his often spiky fragments into the musical equivalent of comfort food.

Correcting a Mozart Deficit

How To Get a Speedy, Remedial Introduction to the Composer

How To Get a Speedy, Remedial Introduction to the Composer

By PIA CATTON [NY Sun, 23 June 2008]

When you really don't know something, it's best just to admit it. And earlier this year, an embarrassing fact emerged: I didn't know Mozart's music as well as I thought I did. The catalyst for this admission came while at the barre during a ballet class. My teacher bellowed, in that way that only ballet teachers can, "Feel the music. This is Mozart."

Soprano Dessay makes a stunning S.F. debut in 'Lucia'

(Photo by Terrence McCarthy)

(Photo by Terrence McCarthy)

By Richard Scheinin [Mercury News, 19 June 2008]

Through the decades, the touchstone role of Lucia in Donizetti's "Lucia di Lammermoor" has been sung in San Francisco by Lily Pons, Joan Sutherland, Beverly Sills and other luminary sopranos. It's time to add Natalie Dessay to the list.

Don Carlo at Royal Opera House

Almost as soon as the 2007/08 season’s details had been published, Angela Gheorghiu decided that the role of Elisabetta di Valois was not for her after all and left Covent Garden’s casting department the challenge of finding a suitable replacement. Soon afterwards Rolando Villazón, the star Mexican tenor destined for the role of Carlo, took a sabbatical on medical advice and cancelled a clutch of international engagements including his planned appearance as Nemorino in the Royal Opera’s L’elisir d’amore.

Anyhow, Villazón returned from his break, the company engaged its former Young Artist Marina Poplavskaya as Elisabetta, the production sold out as soon as it went on sale, and everything appeared to bode well.

Marina Poplavskaya as Elisabetta

Marina Poplavskaya as Elisabetta

On the evidence of this opening night, Villazón is not yet back to full vocal health. When he is on form, he delivers some thrillingly ardent singing, but elsewhere he is frustratingly inconsistent with cracked notes and intonation problems. The Fontainebleau scene was shoddily sung to the extent that it was tempting to leave at the first interval. And Villazón’s nervy, angsty dramatic interpretation had a tendency to reduce the young prince’s struggles with forbidden love and conflicting political duties to the petty tantrums of a moody adolescent.

Rolando Villazón as Don Carlo

Rolando Villazón as Don Carlo

Poplavskaya is potentially a great talent (as evidenced by her outstanding Rachel in last season’s concert performance of La Juive) but sadly the role of Elisabetta di Valois is really beyond her, at least for now. The absence of a full Italianate lirico-spinto tone is perhaps not the end of the world, but her obvious vocal fatigue towards the end of the performance presents a serious problem in a role whose major aria takes place in the final scene. The paleness of her pearly, ‘covered’ soprano is matched by an onstage persona that is far too much the ice maiden, even in the opening scene where we should surely be able to see the spark of youth and vitality that has so captivated the impetuously youthful Carlo.

My comments thus far have perhaps made the whole effort sound disastrous. Fortunately this was not the case. As Posa, Simon Keenlyside gave a world-class performance; human, honest and noble. Ferruccio Furlanetto’s brittle Filippo and Eric Halfvarson’s terrifying Grand Inquisitor each exuded such gravitas of presence that their confrontation was truly gripping. The bells and oppressive Catholic glitz of the auto-da-fé scene packed a real punch, with special praise due to the chorus, while conductor Antonio Pappano seems to have the measure of the piece.

Roland Villazón (Don Carlo) and Simon Keenlyside (Rodrigo)

Roland Villazón (Don Carlo) and Simon Keenlyside (Rodrigo)

Sonia Ganassi’s Eboli was decently-sung in a superficial sort of way, with a big personality and lots of showy fireworks, but her voice and her portrayal seemed to lack an emotional centre. Like Villazón and Poplavskaya, her voice seems a size too small.

The production bears many of Hytner’s hallmarks: uncomplicated situations and character interactions in front of handsome sets in colours evoking the time and place of the setting. The intricate detail used in the individual flats and costumes of Bob Crowley’s designs never takes away from the sense of an elegant visual simplicity. The snow-covered forest of Fontainebleau has a particularly elegant beauty. It is a good-looking, solid staging, and eminently revivable; it seems churlish to complain that it plays things rather safe. Hytner got some boos from the stalls on opening night, which was quite baffling — there were none of the usual triggers which incite audiences to dislike a new production so vehemently.

Ruth Elleson © 2008

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Villazon_Poplavsaya.png image_description=Rolando Villazón (Don Carlo) and Marina Poplavskaya (Elisabetta) in Don Carlo at ROH product=yes product_title=Giuseppe Verdi: Don Carlo product_by= Don Carlo (Rolando Villazón), Elisabetta di Valois (Marina Poplavskaya), Rodrigo (Dimitris Tiliakos/Simon Keenlyside), Philip II (Ferruccio Furlanetto), Princess Eboli (Sonia Ganassi), Tebaldo (Paula Murrihy/Pumeza Matshikiza), Conte di Lerma (Nikola Matišic), Flemish Deputies (Jacques Imbrailo/Krzysztof Szumanski/Kostas Smoriginas/Daniel Grice/Darren Jeffery/Vuyani Mlinde), Grand Inquisitor (Eric Halfvarson), Monk (Robert Lloyd), Voice from Heaven (Anita Watson). Conductor Antonio Pappano. Director Nicholas Hytner. Designs Bob Crowley. Lighting Mark Henderson.Performance of 6 June 2008. product_id=Above: Rolando Villazón (Don Carlo) and Marina Poplavskaya (Elisabetta) in Don Carlo at ROH

All photos by Catherine Ashmore courtesy of Royal Opera House

Don Giovanni. No, the other one

It was composed to a typical buffo libretto by Giovanni Bertati, his collaborator on twenty farces, in Venice in February 1787, where its success inspired someone to send the score to Lorenzo da Ponte in Vienna. He rewrote and expanded the piece, borrowing many of Bertati’s ideas, and gave it to Mozart, who presented his version at Prague’s Tyl Theater on October 29.

One goes to hear Gazzaniga’s Giovanni for foretaste, a prediction, a glimpse of the glory soon to come — a hint of Mozart’s inspiration — but there is little sign of it. The piece opens with an attempted rape and a murder all right, there is a catalogue aria (someone has altered the numbers! Aha!), a peasant wedding, a statue invited to dinner, a ghostly return. There are many moments when you expect to be stunned, enlightened, exalted, shocked, as Mozart’s opera does even on the twentieth hearing — but Gazzaniga keeps missing the chance to startle, to amaze, to create wonder. Donna Anna has the perfect moment for an aria of vengeance when she finds her father’s body (or a duet of vengeance, as in Mozart), but in Gazzaniga … she simply departs, never to return. Don Giovanni has many moments for a seduction duet, but it does not enter his brainless tenor head. Elvira’s last entreaty for Giovanni’s repentance is not an outburst — it’s a full-length aria at a moment when the drama should be snap, snap, snap. The statue’s return sends no cold shivers — the experience of the afterlife has not transformed his vocal manner, as Mozart felt it should. And, having heard Mozart, we know he was right.

It is impossible not to make such comparisons, but it is most unfair to Gazzaniga, and to an evening pleasantly spent. There are lovely tunes in this opera, justifying a long and successful career (51 operas, all but this one forgotten), some elegant ideas, and … a lot that fizzles. With pretty voices, it is a delicious way to pass ninety minutes — ideally by candlelight in a baroque garden theater. (A remodeled warehouse in Toronto’s Distillery District will do in a pinch, and the acoustics are ace.) Gazzaniga was good but ordinary; attending his opera reminds one that Mozart was … extraordinary.

The most effective music, it seemed to me, was the scene of the peasant wedding: the chorus had a Spanish style to it that Mozart did not bother with, and the arias of Biagio (infuriated at his wayward girlfriend) and Maturina (the girl in question, who is falling for the tall, handsome stranger) were very fine and sung by the finest voices in the company, Canadian Opera’s Studio (i.e., their young artists’ program). Justin Welsh, a baritone of energy and smooth production, made the most of Biagio, who has rather more presence in this version — da Ponte and Mozart rightly abbreviated his protest in order not to interrupt the rush of the drama. Gazzaniga gives him a full da capo, and Welsh sang it beautifully — but it interrupts. Maturina was Lisa DiMaria, a sweet, clear, luscious soprano who will mature (no pun intended) into a splendid Susanna and Zerlina in a very short time. I look forward to hearing both of them again.

The other singers, all young, healthy and good actors, did not seem quite so polished, so ready for the major leagues. Jon-Paul Décosse had the most to do as the servant, Pasquariello — he opens the show (just as Leporello does) and sings the catalogue, and serves as his master’s foil in the tomb and dinner scenes. His baritone is strong and supple, but his vigorous antics — sometimes humorous, sometimes menacing — will make him a particular asset to the livelier school of buffo staging. Melinda Delorme, afflicted with a wig that would alienate any lover, made a poignant and energetic Donna Elvira — in this opera the unchallenged prima donna, with two ornamented arias and a comic duet in which she and Maturina fight over “their” man, who of course has set them on each other while he pursues another lady entirely. (That duet’s an idea Bertati might have stolen from Act I of Mozart’s Figaro, but it was probably a buffo staple.) The Commendatore of Andrew Stewart looked gaunt and (as a statue) immobile, but did not succeed in creating shivers where Gazzaniga had neglected to provide them in the score. Michael Barrett (Ottavio) and Adam Luther (Giovanni), the two tenors, sounded uncomfortable with the style of the music, forceful where they should have been graceful, sensuous, ardent. They bit off the ends of notes that should drift into the aether. I suspect both are aiming for nineteenth-century tenor roles, and I applaud that ambition, but precise vocal control always comes in handy.

The production by Tom Diamond was basic and clear, with one annoying, pointless touch: Instead of nobly killing the Commendatore face to face, Don Giovanni sneaked up behind him and stabbed him in the back. This did not suit the story or the personality of our antihero. A consort of nine musicians played the score — undoubtedly it would sound grander with a full orchestra, but the subtle touches of Mozart’s version would still not have been there.

Melinda Delorme as Donna Elvira and Adam Luther as Don Giovanni in the COC’s Ensemble Studio production of Don Giovanni. Photo © 2008 Michael Cooper

Melinda Delorme as Donna Elvira and Adam Luther as Don Giovanni in the COC’s Ensemble Studio production of Don Giovanni. Photo © 2008 Michael Cooper

The second half of this double bill — for a rather larger band of musicians, tackling a self-consciously brilliant score with aplomb — was Stravinsky’s brief retelling of a couple of farmyard folktales, Renard, composed for the Paris salon of his buddy Princess de Polignac — that’s Winnaretta Singer, the sewing machine heiress, to you. The piece was not meant to be staged, merely sung by a quartet of male singers — but Mr. Diamond could not resist. His production derived from World Wide Wrestling matches (the witty costumes were by Yannik Larivée), and no doubt I missed a lot of in-jokes, but the four hammy singers hurled themselves joyously into it. (No limbs were broken — but it was close.) They sang well, too, in clearly pronounced English — again, I especially enjoyed tiny Mr. Welsh, but the standard was high across the board.

John Yohalem

image=http://www.operatoday.com/dong01.png image_description=Andrew Stewart as Il Commendatore and Yannick-Muriel Noah as Donna Anna in the COC’s Ensemble Studio production of Don Giovanni. Photo © 2008 Michael Cooper product=yes product_title=Giuseppe Gazzaniga: Don GiovanniIgor Stravinsky: Renard product_by=Don Giovanni: Don Giovanni (Adam Luther), Donna Anna (Lisa DiMaria / Yannick-Muriel Noah), Donna Elvira (Betty Allison / Melinda Delorme), Donna Ximena (Erin Fisher / Betty Allison), Il Commendatore (Andrew Stewart), Duca Ottavio (Michael Barrett), Maturina (Teiya Kasahara / Lisa DiMaria), Pasquariello (Jon-Paul Décosse / Alexander Hajek / Justin Welsh), Biagio (Justin Welsh), Lanterna (Michael Barrett). Conductor Steven Philcox. Director Tom Diamond. Set and Costume Designer Yannik Larivée. Lighting Designer Bonnie Beecher.

Renard: Tenor 1 (Adam Luther), Tenor 2 (Michael Barrett), Baritone 1 (Justin Welsh / Alexander Hajek), Baritone 2 (Andrew Stewart). Conductor Derek Bate. Director Serge Bennathan. Set and Costume Designer Yannik Larivée. Lighting Designer Bonnie Beecher.

Canadian Opera company Ensemble Studio Production, performance of June 16. product_id=Above: Andrew Stewart as Il Commendatore and Yannick-Muriel Noah as Donna Anna in the COC’s Ensemble Studio production of Don Giovanni.

Photo © 2008 Michael Cooper

June 22, 2008

MEYERBEER: Semiramide

The opera comes from Meyerbeer's early years, before he established himself in France and created his greatest successes (an opening booklet note from Sergio Segalini refers to Meyerbeer in those years as a "Wandering Jew," believe it or not).

The plot of Semiramide mixes palace intrigue with various forms of transvestism, which would seem to be a good recipe for a success on today's stages. Meyerbeer's score finds him in faux-Rossini mode, with the recitatives accompanied by a rather drab piano, perfunctorily played. Ensembles and arias intertwine in typical patterns, and Meyerbeer's melodic gift presents itself as more a promise than accomplishment. However, act two has some attractive numbers, including a sweet aria for princess Tamiri called "D'un genio che m'accende," which Stefania Grasso sings just well enough to allow for an appreciation of the music. The writing for the tenor role, Ircano, pushes the Rossini touch into early Verdi territory, and Aldo Caputo delivers the role with pleasing force and adequate agility. Not a major voice, but an appealing one.

However, in the title role, and with quite a lot of music, Clara Polito will be a trial for many ears, although there are always fans out there with an appreciation for warbly, acidic vocalizing. Polito's intonation suffers in her first numbers. Later she settles, and she has the technique to satisfy some of Meyerbeer's challengers. In the end, and allowing for taste, Polito's instrument simply lacks enough appeal to give her character's music a real chance to impress.

Dynamic, as usual, recorded a live performance. For the most part stage noise does not intervene. In tiny print on the rear of the CD case Dynamic lists the place and location of the recording as the Palazzo Ducale, Martina Franca, in August 2005. Rani Calderon leads the orchestra Internazionale D'Italia and the Slovak Choir of Bratislava. Cnsidering the rarity of the work, the musicians do an adequate, if characterless, job.

Meyerbeer fans surely will want to have this set. Others will have to decide how much interest they have in early Meyerbeer to accept a performance of modest accomplishment.

Chris Mullins

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Meyerbeer_Semiramide.png

image_description=Giacomo Meyerbeer: Semiramide

product=yes

product_title=Giacomo Meyerbeer: Semiramide

product_by=Clara Polito; Aldo Caputo; Eufemia Tufano; Federico Sacchi; Stefania Grasso; Roberto De Biasio. Slovak Choir of Bratislava/Pavol Prochazka. Orchestra Internazionale D’Italia/Rani Calderon. Recorded at Palazzo Ducale, Martina Franca, Italy, August 2006

product_id=Dynamic 533/1-2 [2CDs]

price=$39.99

product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/Drilldown?name_id1=8097&name_role1=1&comp_id=209927&genre=33&bcorder=195&label_id=287

MOZART: Die Zauberflöte — Salzburg 2006

Music composed by W. A. Mozart. Libretto by Emanuel Schikaneder.

First Performance: 30 September 1791, Theater auf der Wieden, Vienna

| Principal Characters: | |

| Sarastro Priest of the Sun | Bass |

| Tamino a Javanese Prince | Tenor |

| An Elderly Priest [‘Sprecher’; Orator, Speaker] | Bass |

| Three Priests | Bass, Tenor, Spoken Role |

| The Queen of Night | Soprano |

| Pamina her daughter | Soprano |

| Three Ladies attendants to the Queen | Two Sopranos, Mezzo-Soprano |

| Three Boys | Two Sopranos, Mezzo-Soprano |

| Papagena | Soprano |

| Papageno a birdcatcher, employed by the Queen | Baritone |

| Monostatos a Moor, overseer at the Temple | Tenor |

| Two Men in Armour | Tenor, Bass |

| Three Slaves | Spoken Role |

Synopsis:

Act I

Scene 1. Among rocky mountains

Pursued by a serpent which he is unable to kill because he has run out of arrows, Prince Tamino faints. Three veiled ladies kill the serpent and fall in love with the handsome stranger, each wishing to stay with him while the others tell their queen what has happened. Eventually all go. A feather-clad, pipe-playing figure arrives: Papageno the bird catcher, who claims to have killed the serpent. The three ladies padlock his mouth to stop him telling more lies. They give Tamino a portrait of Pamina, daughter of the Queen of the Night and when he falls in love with it, they tell him she has been carried off by an evil demon called Sarastro and he swears to save her.

A clap of thunder heralds the arrival of the queen, who promises that her daughter shall be Tamino’s bride if he rescues her. The ladies remove Papageno’s padlock and give Tamino a flute to help him in his quest and, ordering Papageno to go with him, give him a set of bells to use in time of need, explaining that three spirits will guide Tamino to Sarastro’s domain.

Scene 2. A room in Sarastro’s palace

Pamina tries to escape from the advances of the moor Monostatos, who is supposed to be guarding her. She faints and Papageno appears. He and Monostatos take each other for the devil and Monostatos flees. Papageno tells Pamina about the handsome prince who has fallen in love with her and is coming to rescue her and she consoles him on his wifeless state with the assurance that a loving heart will surely find a partner.

Scene 3. Pillars leading to the temples of wisdom, reason and nature

The three spirits leave Tamino in front of the pillars. He is turned back by unseen voices as he tries to enter the first two temples and a priestly figure bars his way to the third. From this man, the speaker, Tamino learns that although Pamina is in Sarastro’s realm, things are not as the Queen of the Night has represented them. But Tamino is not yet fit to understand the mysteries of the temples where Sarastro rules in wisdom. The Speaker disappears, but the voices tell Tamino that Pamina is alive. He expresses his joy by playing the flute and animals gather round to listen. He hears Papageno’s pipes and sets off to find him. Meanwhile Papageno and Pamina have been following the sound of the flute. They are overtaken by Monostatos and slaves who are about to drag them off in chains when Papageno remembers his magic bells. Monostatos and the slaves dance off, forgetting their intention.

Sarastro and priests of the brotherhood arrive and Pamina tells him that she has tried to escape because of Monostatos. Sarastro is kind, but tells her that she cannot yet be set free because of her mother’s evil influence.

Monostatos has captured Tamino. Pamina and Tamino rush into each other’s arms. Sarastro orders that Monostatos be whipped and Tamino and Papageno be led into the temple to be purified.

Act II

Scene 1. A grove in Sarastro’s domain

Sarastro urges the brotherhood to allow Tamino to undergo the trials that will make him worthy to join their band, explaining that the gods have ordained Pamina as Tamino’s wife; it is for this reason that he took her from her mother, whose aim is to destroy the temple.

Scene 2. A temple courtyard at night

Two priests ask Tamino and Papageno if they are prepared to undergo the trials. Tamino is ready. Papageno demurs, but weakens when told that the gods have a wife in store for him, just like himself and called Papagena. The priests impose silence on them, warn them against the wiles of women and leave them in the dark. The three ladies appear and threaten vengeance, but Tamino ignores them, advising Papageno to do the same. The ladies are driven off by the brotherhood. The priests commend Tamino for his steadfastness and lead him and the reluctant Papageno off to the next trial.

Scene 3. A garden lit by the moon

Monostatos tries to kiss the sleeping Pamina, but is frightened off by the arrival of the Queen of the Night, who gives Pamina a dagger, ordering her to kill Sarastro and bring back to her the circle of the sun which had been given to Sarastro by her late husband. When Pamina expresses her revulsion at the though of killing, Monostatos tells her that she can only save herself and her mother by loving him. Sarastro drives him away and assures Pamina that her mother is safe from him, since no thoughts of vengeance are permitted in his realm.

Scene 4. A hall

Tamino and Papageno are led in by the priests and left alone. Papageno complains of thirst and an old woman gives him water, tells him he is her sweetheart and disappears. The spirits bring back Tamino’s flute and Papageno’s bells, which had been taken from them. They also bring a feast which Papageno attacks with gusto, while Tamino abstains, playing the flute instead.

The sound draws Pamina, who is distressed when Tamino refuses to speak to her. Even Papageno, his mouth full of food, does not answer. She longs for death.

Scene 5. A subterranean vault

The priests rejoice at Tamino’s progress. Sarastro tells Tamino and Pamina to bid each other farewell for ever. Papageno is rejected by the brotherhood, but replies that there are more of his kind than theirs in the world. All he wants is a wife. The old woman appears; and, when he reluctantly promises to be faithful, changes into a young and beautiful girl, Papagena. But she is taken away by the priests.

Scene 6. A garden

The three spirits stop Pamina from killing herself, assuring her that Tamino would be heartbroken; they offer to take her to him.

Scene 7. Two mountains, one spitting fire, the other with a waterfall

Two men in armor guard the approaches. They tell Tamino that he may now speak to Pamina, and together they undergo the ordeals of fire and water, Tamino playing the flute as they go.

Scene 8. A garden

The boys prevent Papageno from committing suicide in his despair at the loss of Papagena. Following their advice, he plays his magic bells and she appears. They make joyful plans for a philoprogenitive future.

Scene 9. An underground vault

The Queen of the Night, her ladies and Monostatos, who has joined them in the hope of getting Pamina, attack the temple but are repulsed and defeated.

Scene 10. The temple of the sun

Sarastro leads the brotherhood in celebration of the triumph of light, and Tamino and Pamina are united in marriage.

[Synopsis Source: Opera~Opera]

Click here for the complete libretto.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Zauberflote_Salzburg_2006.png image_description=Genia Kühmeier (Pamina), Diana Damrau (Königin der Nacht) [Photo: Salzburger Festspiele] audio=yes first_audio_name=W. A. Mozart: Die Zauberflöte first_audio_link=http://www.operatoday.com/zauberflote2.m3u product=yes product_title=W. A. Mozart: Die Zauberflöte product_by=René Pape (Sarastro)Paul Groves (Tamino)

Genia Kühmeier (Pamina)

Christian Gerhaher (Papageno)

Irina Bespalovaite (Papagena)

Diana Damrau (Queen of the Night)

Franz Grundheber (Speaker/First Priest)

Inga Kalna (First Lady)

Karine Deshayes (Second Lady)

Ekaterina Gubanova (Third Lady)

Members of the Vienna Boys' Choir (Three Boys )

Xavier Mas (Second Priest)

Michael Autenrieth (Third Priest)

Burkhard Ulrich (Monostatos)

Simon O'Neill (First Armed Man)

Peter Loehle (Second Armed Man)

Konzertvereinigung Wiener Staatsopernchor

Wiener Philharmoniker

Riccardo Muti (cond.)

Live performance, 29 July 2006, Großes Festspielhaus, Salzburg

A rare treasure in Saint Louis. . .

Although Cosa rara’s eponymous rare treasure concerns the honesty of a beautiful woman, Opera Theatre surely enjoyed the play on words in presenting this rarely performed but once-treasured opera. The company has successfully contextualized Mozart in its last few seasons by presenting works of his contemporaries, including Grétry’s Beauty and the Beast (1771) and Cimarosa’s The Secret Marriage (1792). Vincent Martín y Soler’s opera continues this trend, since nearly everything about Una cosa rara reminds us of its more familiar Mozartian brethren.

Born in Spain two years before Mozart, Martín lacked his contemporary’s astonishing precocity, though by his early twenties he had composed comic operas for many important Italian towns. He moved to Vienna in 1785, four years after Mozart’s own arrival. The following year each man composed an opera for Emperor Joseph II’s Italian theater. Mozart inaugurated his partnership with librettist Lorenzo da Ponte, culminating in Le nozze di Figaro. Martín likewise collaborated with da Ponte on his comic opera, Una cosa rara. Figaro’s modest success in May 1786 was overshadowed by Una cosa rara’s triumphant debut eight months later. In October 1787 Martín penned a follow-up hit with the immensely popular pastoral work L’arbore di Diana. Less than a month later, Don Giovanni opened in Prague. In it, Mozart acknowledged his peer’s popularity by quoting a tune from Cosa rara during the Act II dinner entertainment. These textual and musical links to Mozart are not just historical happenstance, but structurally important in Cosa rara. Da Ponte’s influence weighs heavily, with both the plot and the characters echoing Figaro and Così fan tutte. Although Martín’s musical style lacks the spice of Mozart at his best, Cosa rara is perfectly passable as good 18th century opera. For us just as for the Viennese, Martín’s pleasant pastoral ditties digest easily.

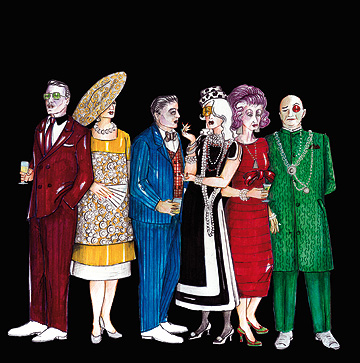

Stage director Chas Rader-Schieber conceived Opera Theatre’s Cosa rara as a farcical world of warped whimsy, albeit with a rather friendly touch. His vision was amply fulfilled by the aforementioned sheep on wheels, pink flamingos, garden gnomes, etc. These flamingos extended beyond mere props, even decorating the outdoor gardens at intermission. The set and the costumes seemed to get as much or more attention than the music, since each character’s entrance was accompanied by applause or laughter. The costumes continued to get more and more outlandish, culminating in the high (or low?) point of the Queen’s Act II hunting outfit, which featured giant pink glittering antlers affixed to her head. It was all extremely silly, but the cast (and audience by extension) seemed to have a ball.

Although the visual spectacle of this production dominated at times, the vocal performances were solid as well, with some truly excellent moments. Soprano Mary Wilson was both impressive and endearing as the dotty Queen of Spain, and she certainly seemed to enjoy her silly onstage shenanigans. She wowed the audience during many of her numbers, particularly the virtuoso rondo in Act II. A great example of Cosa rara’s more elevated musical style for the noble characters, Wilson nailed the difficult technical passages in this aria with finesse and good taste in ornamentation. Her son the Prince was interpreted in a delightfully hammy manner by tenor Alek Schrader. With his over the top pink and black sequined costume, his platinum blond wig a cross between Madame Pompadour and rockabilly à la Jerry Lee Lewis, Schrader titillated the audience throughout. His difficult Act II recitative and aria was very nicely sung, although perhaps one might desire a little more power in the finish. Corrado’s part, sung by Paul Appleby, was much less substantial, with only short solos.

Maureen McKay and Alek Schrader

Maureen McKay and Alek Schrader

On to the peasants! Soprano Maureen McKay was absolutely delightful as the ingenuous shepherdess Lilla, and had the audience in stitches from her first entrance, running frantically onto stage and literally throwing herself at the Queen’s feet. Though this particular performance had a few isolated strained notes in the higher register, McKay has a lovely clear voice, and her perfect acting really helped make the production. Lilla’s lover Lubino, a rather dimwitted impetuous shepherd, was well-served by Keith Phares’ rich baritone voice and excellent diction. Phares particularly amused the audience with his ridiculous Act I parody of a vengeance aria. If Lilla and Lubino represent the perfect shepherd couple, their counterparts Ghita and Tita offer (still more) comic relief. Ghita was saucily interpreted by soprano Kiera Duffy, while Matthew Burns took the bass role of Tita. The two bickered impressively, interspersing their arguments with hilarious make-out sessions. Both singers had some of the more difficult patter singing in Cosa rara, which they managed with aplomb. Matthew Burns’s voice was especially impressive, as was his stellar diction.

The orchestra members, drawn from the Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra, were well conducted by Corrado Rovaris. They performed the 18th century style cleanly and followed the singers sensitively, with the only minor shortcoming being the occasional trampling of forte-piano alternations.

Hugh Macdonald’s new English singing translation certainly added to the hilarity of it all. He clearly reveled in fashioning silly rhymes such as mooning and spooning and swooning, and even alerted the audience to the arrival of the melody famously quoted in Don Giovanni. His new translation played a major role in the successfully slapstick comedy of this Cosa rara, cramming in jokes, puns, wink-wink references, and general silliness by the handful.

Opera Theatre’s rare treasure in this performance seemed to lie not in the revitalization of some forgotten masterpiece, but in presenting an opera completely without pretensions, a perfectly frivolous summer treat.

Erin Brooks © 2008

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Cosa_rara01.png image_description=Mary Wilson as Queen Isabella (Photo by Ken Howard courtesy of Opera Theatre of Saint Louis) product=yes product_title=Vincent Martín y Soler: Una cosa rara o sia Belleza ed onestá [A Rare Treasure, or Beauty and Honesty] product_by=Queen Isabella (Mary Wilson); Prince Giovanni (Alek Schrader); Corrado, (Paul Appleby); Lilla (Maureen McKay); Lubino (Keith Phares); Tita (Matthew Burns); Ghita (Kiera Duffy); Lisargo (David Kravitz). Musicians of the Saint Louis Symphony, conducted by Corrado Rovaris. Directed by Chas Rader-Shieber, with sets by David Zinn and costumes by Clint Ramos. product_id=Above: Mary Wilson as Queen IsabellaAll photos by Ken Howard courtesy of Opera Theatre of Saint Louis

Choral Music by Dvořák and Brahms

Yet his Requiem, Op. 89, which received its premiere in 1891, is an equally find work that deserves a similar kind of popularity. While stated explicitly with reference to Brahms’ Deutsches Requiem all Requiems are, ultimately for the living, and the approach each composer has taken in setting the text of this rite also reflects something of the intended audience of the piece.

Composers in the nineteenth century approached the Requiem Mass in various ways, from the dramatic setting by Berlioz to the more personal expression of the sentiments of the rite by Brahms in his Deutsches Requiem. Dvorak treated the Requiem in a more conventional manner by using the text of the Requiem Mass associated with the Catholic liturgy, an idiom that should be familiar to the audience he addressed. While it bows to convention, such adherence to tradition should not suggest anything mundane. On the contrary, Dvorak’s setting bears attention for the way in which he expressed this text in one of the finer scores of his artistic maturity. A work for four vocal soloists, chorus, and orchestra, it is a powerful large-scale work that brings to mind some of the composer’s symphonic music, while simultaneously relying on choral sonorities for some of its more poignant effects. As occurs in Dvorak’s later symphonies, the interplay of textures is an important aspect of the score, which is as colorful as some of the composer’s operas.

The second section, the Gradual in which the text reiterates the prayer for peace (“Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine, / Et lux perpetua luceat eis. / In memoria aeterna erit justis / ab auditione mala non timebit.”) the juxtaposition of the soprano solo with the chorus is memorable, especially in the context of the sometimes transparent orchestration. Likewise, the Dies irae that follows involves the traditional melodic formulation associated with the chant and also the exploits the thunderous sound of percussion and brass. In contrast to the relentless trumpets of Verdi’s well-known Requiem, the softer, more subdued sonorities that Dvorak used in his setting create a different, more intimate effect. In contrast to the terrors at the prospect of divine judgment, the listener gains a sense of consolation and the prospect of eternal peace. In these and other ways, Dvorak approached the Requiem with the same sense for building on tradition as he did in his symphonic works. The result is a score that deserves to be heard more often, not only on recordings, but also in live performances.

This recording of Dvorak’s Requiem preserves a performance given on 13 November 2005 at a concert given in the memory of Grand Duke Adolf of Luxemburg (also Duke of Nassau), and the quality of the effort is apparent from the outset. The solo parts are sung by Mechthild Bach (soprano), Stefanie Irányi (alto), Markus Schäfer (tenor), and Klaus Mertens (bass). Mertens is, perhaps, the most familiar soloist, also performs Brahms’ Vier ernste Gesänge on this recording. He is balanced well by Schäfer, whose ringing sound captures well the solo line for the tenor. Mechthild Bach brings some fine touches to the soprano part, which involves some sustained passages that demand an accomplished winder. Likewise, Stefanie Iránji works well with Bach and other soloists when the concertato-like sonorities contrast the full chorus throughout much of the work.

Even with a less extensive discography than that which exists for the Stabat Mater, Dvorak’s Requiem is available in several fine performances, and this particular performance can be counted among the notable ones. The sound on this particular Hänssler recording is, perhaps, a bit close and, as a result, does not always allow for the full sonorities of chorus or the combined chorus and orchestra to have the ambiance that would emerge in the actual hall. While not completely dry, it lacks the resonance one would associate with Dvorak. Even so, the sound is quite crisp and captures well the clearly articulated texts. The diction of the soloists is matched by the similarly precise entrances of the entire chorus, which Doris Hagel leads masterfully.

This recording includes on the second disc a performance of Brahms’ Vier ernste Gesänge by Klaus Mertens. Since the length of Dvorak’s Requiem forces a recording onto two CDs, the inclusion of this late work by Brahms is quite welcome, especially since it involves Mertens, whose performance in Dvorak’s Requiem is impressive. A cycle of settings for solo voice, the four songs have texts from the Old and New Testament that deal, in a sense, with the last things, that is, those enduring points of contemplation regarding existence, love, and salvation. Neither a Requiem, per se, nor funereal in tone, the Vier ernste Gesänge from 1896, the year before its composer died, are nonetheless reflective in nature, and Mertens’ interpretation captures that sense well. His resonant voice and fine diction are essential to the quality of this recording.

James L. Zychowicz

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Dvorak_Brahms_Requiems.png

image_description=Antonin Dvorak: Requiem, Op. 89; Johannes Brahms: Vier erste Gesänge, Op. 121

product=yes

product_title=Antonin Dvorak: Requiem, Op. 89; Johannes Brahms: Vier erste Gesänge, Op. 121

product_by=Mechthild Bach, soprano, Stefanie Irányi, alto, Markus Schäfer, tenor, Klaus Mertens, bass. Kantorei der Schlosskirch Weilburg, Capella Weilburgensis, Doris Hegel, conductor

product_id=Profil Medien PH06050 [2CDs]

price=$34.99

product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/Drilldown?name_id1=3313&name_role1=1&comp_id=58859&genre=43&bcorder=195&label_id=5269

June 19, 2008

Mozart and Lortzing from Hamburg Opera on film

Cinematography, hair, costumes: all are redolent of a proud stage tradition adapted - not always with subtlety - to the needs of the camera, circa 1970. In 2008, what might have seemed hopelessly dated, even musty, actually carries a sort of "toy world" appeal.

The chief drawback of most filmed opera, especially from this era, is that the intimacy and varied perspective of the camera cannot mitigate the artificiality of the sound, which not only relies on lip syncing but also maintains a consistently flat audio stage, belying the naturalistic movements of the both camera and actors. To the credit of both the Lortzing and Mozart sets, excellent conductors lead energetic performances from the Hamburg Philharmonic State Orchestra. Charles Mackerras deals with Lortzing's perky - perhaps excessively perky - score to the comic Zar und Zimmerman with flair and good spirits. An entire opera based on a series of mistaken identities (Peter the Great has gone "undercover" to learn more about the world), Zar und Zimmerman has never really established itself outside of its home country. This video doesn't exactly make one regret that fact, but it does offer an extremely attractive cast doing their best to make the time pass pleasantly. Lucia Popp's absolutely sweet Marie stands out, with Raymond Wolansky as Peter the Great right behind her. In the tenor role of Peter Ivanov, Peter Haage's chubby male ingenue may annoy some as much as he did your reviewer.

Hans Sotin has the comic villain role in the Lortzing, and he reappears in Die Zauberflöte as Sarastro. Veteran Horst Stein leads an old-fashioned performance, appropriately enough for this production, directed with a disappointingly scant amount of invention by Sir Peter Ustinov. The illustrious cast included Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau as the Speaker, Nicolai Gedda as Tamino, Edith Mathis as Pamina, Cristina Deutekom as the Queen of the night, and William Workman as Papageno. Their vocal contributions are all solid, but Ustinov fails to inspire them to offer more than perfunctory acting. Deutekom sings a fearsome Queen while her face remains entirely impassive. No one lip syncs all that well, but Workman in particular barely seems to be trying. The three boys compete to find pitch, with no winner. Monostatos appears in blackface. All in all, despite the camera, the opera remains stagebound and rarely shows sign of life.

Hans Sotin has the comic villain role in the Lortzing, and he reappears in Die Zauberflöte as Sarastro. Veteran Horst Stein leads an old-fashioned performance, appropriately enough for this production, directed with a disappointingly scant amount of invention by Sir Peter Ustinov. The illustrious cast included Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau as the Speaker, Nicolai Gedda as Tamino, Edith Mathis as Pamina, Cristina Deutekom as the Queen of the night, and William Workman as Papageno. Their vocal contributions are all solid, but Ustinov fails to inspire them to offer more than perfunctory acting. Deutekom sings a fearsome Queen while her face remains entirely impassive. No one lip syncs all that well, but Workman in particular barely seems to be trying. The three boys compete to find pitch, with no winner. Monostatos appears in blackface. All in all, despite the camera, the opera remains stagebound and rarely shows sign of life.

The Lortzing DVD preserves a charming performance of an opera little known in the US, so it is worth a look. Fine DVDs of Die Zauberflöte, however, can easily be acquired, so anyone thinking of this set should either be a fan of the cast or a devotee of mediocre TV direction.

Chris Mullins

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Lortzing.png image_description=Albert Lortzing: Zar und Zimmermann product=yes product_title=Albert Lortzing: Zar und Zimmermann product_by=Peter the Great (Raymond Wolansky), Peter Ivanov (Peter Haage), Van Bett (Hans Sotin), Marie (Lucia Popp), Admiral Lefort (Herbert Fliether), Lord Syndham (Noël Mangin), Marquis de Châteauneuf (Horst Wilhelm), Widow Browe (Ursula Boese), Officer (Franz Grundheber). Ballet and Chorus of the Hamburg State Opera, The Philharmonic State Orchestra Hamburg, Charles Mackerras, conductor. product_id=Arthaus Musik 101269 [DVD] price=$29.98 product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/Drilldown?name_id1=7315&name_role1=1&comp_id=197478&bcorder=15&label_id=4357Karajan opera highlights on Classics for Pleasure

The Cosi fan Tutte is the well-regarded 1954 set, in dry, flat mono. In its 72 minutes, the highlights favor act one and the first two scenes of act two. Most of the opera's most beloved music does come in these sections, but any sense of the dramatic resolution gets lost in the quick jump to the supposedly joyous final ensemble.

Is it just the faded quality of the mono sound that makes it difficult for your reviewer to find the sparkle and charm that the performance promises? Elisabeth Schwarzkopf sings with style and accuracy, but little warmth. Nan Merriman's Dorabella makes the most of her act one solo, "Smanie implacabili," infusing her reading with an edge of anger reminiscent of Donna Elvira. After that, she slips into the ensembles and loses any profile. Rolando Panerai and Leopold Simoneau, as the two lover/soldiers, sound appropriately fresh. Not much of Sesto Bruscantini's Don Alfonso can be heard, which may explain the lack of dramatic impetus. Ultimately, Karajan seems to have gotten the note-perfect performance he wanted, but the lack of edge tends to make the numbers run together.

The 1971 Fidelio finds Karajan urging on the drama. The strings cut through impatiently, horns ring out with emphatic despair. But every moment seems to come in its own little interpretive capsule, unconnected to the next. Jon Vickers, who had already offered a remarkable Florestan on the famed Klemperer set, may be acting when he lets his voice sound worn at times, or it may be the singer coping with Karajan's sometimes languid tempo. Helga Dernesch faces a similar challenge in the rhythmically fragmented "Abscheulicher!" solo. She relies more on lungpower than interpretation, but that also has its merits. The rest of the cast makes little impression, although Karl Ridderbusch makes Rocco less annoying than the character can be.

The 1971 Fidelio finds Karajan urging on the drama. The strings cut through impatiently, horns ring out with emphatic despair. But every moment seems to come in its own little interpretive capsule, unconnected to the next. Jon Vickers, who had already offered a remarkable Florestan on the famed Klemperer set, may be acting when he lets his voice sound worn at times, or it may be the singer coping with Karajan's sometimes languid tempo. Helga Dernesch faces a similar challenge in the rhythmically fragmented "Abscheulicher!" solo. She relies more on lungpower than interpretation, but that also has its merits. The rest of the cast makes little impression, although Karl Ridderbusch makes Rocco less annoying than the character can be.

At an hour of music without dialogue, a Fidelio highlights set may be the way to go for some listeners, as it contains much of the opera's best music. Both this Fidelio and the Cosi certainly deserve acknowledgement as offering expert performances in many regards, but with strong competition from other sets for both operas, these two highlights CDs can best be recommended to die-hard fans of HvK.

Chris Mullins

image=http://www.operatoday.com/karajan_cosi.png image_description=Mozart: Così fan tutte (highlights) product=yes product_title=Mozart: Così fan tutte (highlights) product_by=Schwarzkopf, Merriman, Simoneau, Panerai, Otto, Bruscantini, Philharmonia Orchestra, Herbert von Karajan product_id=EMI Classics for Pleasure 393 3692 [CD] price=$7.99 product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/Drilldown?name_id1=8429&name_role1=1&name_id2=56047&name_role2=3&label_id=1132&bcorder=361&comp_id=17374Discover forgotten operettas

The Ohio Light Opera reconstructs shows to their past splendor for 30th anniversary

By Elaine Guregian [Akron Beacon Journal, 19 June 2008]

One era's giant scandal is another era's forgotten memory.

Take, for example, the Mayerling Incident.

SF Opera scores a triumph

[Photo by Terrence McCarthy courtesy of San Francisco Opera]

[Photo by Terrence McCarthy courtesy of San Francisco Opera]

by Jason Victor Serinus [Bay Area Reporter, 19 June 2008]

Ariodante's plot may have its giggle-inducing inanities, but its oft-florid music is glorious. Given the excellence of SFO General Director David Gockley's cast, we will be extremely fortunate to experience another equally glowing rendition of Handel's seldom-performed opera of 1735 in our lifetimes.

A Slimmed-Down Diva Keeps Her Vocal Heft

By VIVIEN SCHWEITZER [NY Times, 18 June 2008]

By VIVIEN SCHWEITZER [NY Times, 18 June 2008]

LONDON — The drama following the 2004 dismissal of the soprano Deborah Voigt from a production of Strauss’s “Ariadne auf Naxos” at the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden here had many elements of the work itself: an opera within an opera that blends comic and tragic aspects and caricatures the lofty ideals of high art. Ms. Voigt’s dismissal, because she was too large to wear the cocktail dress stipulated by the director or adhere to his staging concepts, prompted an avalanche of international interest that ranged from buffa laughs about fat ladies singing to ponderous editorials about the meaning of “sacred art” versus Hollywood ideals of beauty.

June 17, 2008

A novel approach to modern opera

Robin Usher [The Age, 17 June 2008]

Robin Usher [The Age, 17 June 2008]

LIKE many love affairs, Andrew Schulz's relationship with opera has its ups and downs. "I have mixed feelings about it and I become very frustrated at opera performances that are ossified and lack vitality," he says.

Early Music Festival Opens in the Key of DIY

By Anne Midgette [Washington Post, 17 June 2008]

By Anne Midgette [Washington Post, 17 June 2008]

The early music movement has come a long way in terms of acceptance and understanding, but it still projects a sense of do-it-yourself. The Washington Early Music Festival, which opened its fourth season Sunday night, offers, in this spirit, a nice balance of professionalism and small-scale intimacy. On the one hand, it casts a spotlight on the breadth of early music that has grown up in this area in the last couple of decades -- all of the performers this season (which runs through June 28) are locally based. On the other, it still feels appealingly homemade.

Euro keeps scared music lovers from Vienna state opera

[Earth Times, 17 June 2008]

[Earth Times, 17 June 2008]

Vienna - The Vienna State Opera recorded this season's lowest attendance rate during Austria's Euro 2008 match against Germany - because music lovers were scared by the nearby Euro fan zone, the opera said Tuesday. The opera filled only 79 per cent of its seats on the Monday match night, compared with an average of 99 per cent during the season.

Spivs, rockers and sopranos

By Andrew Clark [Financial Times, 17 June 2008]

By Andrew Clark [Financial Times, 17 June 2008]

The test of any Ariadne, beyond the quality of singing, is whether it makes sense of the work’s inbuilt collisions – between vulgar comedy and high seriousness, idealism and pragmatism, modernist self-consciousness and old-world geniality, sincerity and hubris.

'Tosca' Time at the New York Philharmonic

By JAY NORDLINGER [NY Sun, 16 June 2008]

By JAY NORDLINGER [NY Sun, 16 June 2008]

In these last weeks of the 2008-09 season, the New York Philharmonic is providing a night at the opera. They do this every once in a while — put on an opera-in-concert. The current offering is Puccini's "Tosca." And the Philharmonic will perform it twice more, tomorrow and Thursday nights.

June 15, 2008

Plácido Domingo’s miraculous autumn

The direction was self-managed by the singing company with very few “Italian-style rehearsals” (the pun is reportedly due to Plácido Domingo himself). Despite lacking costumes and props, the bodies kept moving and interacting throughout, so that, in the end, the chairs remained empty most of the time. The “Italian-style” label was also applicable to the tenor’s German diction, with consonants softened and vowels broadly open; probably more gracefully that any native singer would, yet not marring the text’s understanding. Other than a handful of specialists, actually, who really understands Wagner’s language? Ask any educated German for confirmation…

A 67-year-old Siegmund would make news anyway, but Domingo’s is simply a miracle for clarion tones, power and tenderness. This February at La Scala, where he sang the title-role in Alfano’s Cyrano de Bergerac, I had noticed his intelligence in overcoming the disadvantages of age through the frugal management of his resources until the final act. This was a different case, since Siegmund disappears after Act 2, so no such contrivances were needed and his stage charisma could deploy right from the start in a perfect combination of acting skills and velvety vocal color.

Nobly pathetic when retelling the mishaps of his family, he unsheathed sarcasm and proud challenge during his confrontations with Hundig, conjured delicate emotions in the hymn to Spring and warlike excitement in his appeal to the sword (“Nothung! Nothung!”) at the end of Act 1. Even Evelyn Herlitzius, a mercurial Brünnhilde of no particular firmness in her high tones, could not escape his manly spell during their duet on the battlefield in Act 2. With her beautiful central range, perfect intonation, and the coy passion of certain feminine motions, Waltraud Meier’s Sieglinde proved a worth partner for the hero; as a duly hateful Hundig, young René Pape could well abuse her with his marble bass, but could hardly shake her soft dignity.

Equally well matched (so to say) was the godlike couple in the Walhalla: Alan Held, the experienced Wagnerian from Washburn, Illinois, made an embittered but quite not unsympathetic Wotan, while Jane Henschel was a Fricka of inflexible decision and generous vocal means. In the patrol of Valkyries, Michelle Marie Cook (Gerhilde) and Gemma Coma-Alabert (Rossweisse) emerged for their burnished instruments, while brave Inés Moraleda (Grimgerde) reaped additional applause and flowers from the audience because of her noticeably advanced pregnancy. Conductor Sebastian Weigle, the home orchestra and everybody else were fêted much beyond the Liceu’s usual restraint; as to Don Plácido, his (purposely?) belated appearance for the curtain calls unleashed a standing ovation that was little short of mutinous.

Carlo Vitali

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Meier_Domingo-ph-Bofill_pet.png image_description=Waltraut Meier (Sieglinde), Plácido Domingo (Siegmund) [Photo: Antoni Bofill] product=yes product_title=Richard Wagner: Die Walküre product_by=Gran Teatre del Liceu, BarcelonaSemi-staged production

Performance of 1 June 2008 product_id=Above: Waltraut Meier (Sieglinde), Plácido Domingo (Siegmund)

Photo © Antoni Bofill

MOZART: Die Zauberflöte — Salzburg 2005

Music composed by W. A. Mozart. Libretto by Emanuel Schikaneder.

First Performance: 30 September 1791, Theater auf der Wieden, Vienna

| Principal Characters: | |

| Sarastro Priest of the Sun | Bass |

| Tamino a Javanese Prince | Tenor |

| An Elderly Priest [‘Sprecher’; Orator, Speaker] | Bass |

| Three Priests | Bass, Tenor, Spoken Role |

| The Queen of Night | Soprano |

| Pamina her daughter | Soprano |

| Three Ladies attendants to the Queen | Two Sopranos, Mezzo-Soprano |

| Three Boys | Two Sopranos, Mezzo-Soprano |

| Papagena | Soprano |

| Papageno a birdcatcher, employed by the Queen | Baritone |

| Monostatos a Moor, overseer at the Temple | Tenor |

| Two Men in Armour | Tenor, Bass |

| Three Slaves | Spoken Role |

Synopsis:

Act I

Scene 1. Among rocky mountains

Pursued by a serpent which he is unable to kill because he has run out of arrows, Prince Tamino faints. Three veiled ladies kill the serpent and fall in love with the handsome stranger, each wishing to stay with him while the others tell their queen what has happened. Eventually all go. A feather-clad, pipe-playing figure arrives: Papageno the bird catcher, who claims to have killed the serpent. The three ladies padlock his mouth to stop him telling more lies. They give Tamino a portrait of Pamina, daughter of the Queen of the Night and when he falls in love with it, they tell him she has been carried off by an evil demon called Sarastro and he swears to save her.

A clap of thunder heralds the arrival of the queen, who promises that her daughter shall be Tamino’s bride if he rescues her. The ladies remove Papageno’s padlock and give Tamino a flute to help him in his quest and, ordering Papageno to go with him, give him a set of bells to use in time of need, explaining that three spirits will guide Tamino to Sarastro’s domain.

Scene 2. A room in Sarastro’s palace

Pamina tries to escape from the advances of the moor Monostatos, who is supposed to be guarding her. She faints and Papageno appears. He and Monostatos take each other for the devil and Monostatos flees. Papageno tells Pamina about the handsome prince who has fallen in love with her and is coming to rescue her and she consoles him on his wifeless state with the assurance that a loving heart will surely find a partner.

Scene 3. Pillars leading to the temples of wisdom, reason and nature

The three spirits leave Tamino in front of the pillars. He is turned back by unseen voices as he tries to enter the first two temples and a priestly figure bars his way to the third. From this man, the speaker, Tamino learns that although Pamina is in Sarastro’s realm, things are not as the Queen of the Night has represented them. But Tamino is not yet fit to understand the mysteries of the temples where Sarastro rules in wisdom. The Speaker disappears, but the voices tell Tamino that Pamina is alive. He expresses his joy by playing the flute and animals gather round to listen. He hears Papageno’s pipes and sets off to find him. Meanwhile Papageno and Pamina have been following the sound of the flute. They are overtaken by Monostatos and slaves who are about to drag them off in chains when Papageno remembers his magic bells. Monostatos and the slaves dance off, forgetting their intention.

Sarastro and priests of the brotherhood arrive and Pamina tells him that she has tried to escape because of Monostatos. Sarastro is kind, but tells her that she cannot yet be set free because of her mother’s evil influence.

Monostatos has captured Tamino. Pamina and Tamino rush into each other’s arms. Sarastro orders that Monostatos be whipped and Tamino and Papageno be led into the temple to be purified.

Act II

Scene 1. A grove in Sarastro’s domain

Sarastro urges the brotherhood to allow Tamino to undergo the trials that will make him worthy to join their band, explaining that the gods have ordained Pamina as Tamino’s wife; it is for this reason that he took her from her mother, whose aim is to destroy the temple.

Scene 2. A temple courtyard at night

Two priests ask Tamino and Papageno if they are prepared to undergo the trials. Tamino is ready. Papageno demurs, but weakens when told that the gods have a wife in store for him, just like himself and called Papagena. The priests impose silence on them, warn them against the wiles of women and leave them in the dark. The three ladies appear and threaten vengeance, but Tamino ignores them, advising Papageno to do the same. The ladies are driven off by the brotherhood. The priests commend Tamino for his steadfastness and lead him and the reluctant Papageno off to the next trial.

Scene 3. A garden lit by the moon

Monostatos tries to kiss the sleeping Pamina, but is frightened off by the arrival of the Queen of the Night, who gives Pamina a dagger, ordering her to kill Sarastro and bring back to her the circle of the sun which had been given to Sarastro by her late husband. When Pamina expresses her revulsion at the though of killing, Monostatos tells her that she can only save herself and her mother by loving him. Sarastro drives him away and assures Pamina that her mother is safe from him, since no thoughts of vengeance are permitted in his realm.

Scene 4. A hall

Tamino and Papageno are led in by the priests and left alone. Papageno complains of thirst and an old woman gives him water, tells him he is her sweetheart and disappears. The spirits bring back Tamino’s flute and Papageno’s bells, which had been taken from them. They also bring a feast which Papageno attacks with gusto, while Tamino abstains, playing the flute instead.

The sound draws Pamina, who is distressed when Tamino refuses to speak to her. Even Papageno, his mouth full of food, does not answer. She longs for death.

Scene 5. A subterranean vault

The priests rejoice at Tamino’s progress. Sarastro tells Tamino and Pamina to bid each other farewell for ever. Papageno is rejected by the brotherhood, but replies that there are more of his kind than theirs in the world. All he wants is a wife. The old woman appears; and, when he reluctantly promises to be faithful, changes into a young and beautiful girl, Papagena. But she is taken away by the priests.

Scene 6. A garden

The three spirits stop Pamina from killing herself, assuring her that Tamino would be heartbroken; they offer to take her to him.

Scene 7. Two mountains, one spitting fire, the other with a waterfall

Two men in armor guard the approaches. They tell Tamino that he may now speak to Pamina, and together they undergo the ordeals of fire and water, Tamino playing the flute as they go.

Scene 8. A garden

The boys prevent Papageno from committing suicide in his despair at the loss of Papagena. Following their advice, he plays his magic bells and she appears. They make joyful plans for a philoprogenitive future.

Scene 9. An underground vault

The Queen of the Night, her ladies and Monostatos, who has joined them in the hope of getting Pamina, attack the temple but are repulsed and defeated.

Scene 10. The temple of the sun

Sarastro leads the brotherhood in celebration of the triumph of light, and Tamino and Pamina are united in marriage.

[Synopsis Source: Opera~Opera]

Click here for the complete libretto.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/damrau_queen.png image_description=Diana Damrau as Queen of the Night audio=yes first_audio_name=W. A. Mozart: Die Zauberflöte first_audio_link=http://www.operatoday.com/zauberflote1.m3u product=yes product_title=W. A. Mozart: Die Zauberflöte product_by=Sarastro (René Pape)Tamino (Michael Schade)

Queen of the Night (Anna-Kristiina Kaappola)

Pamina (Genia Kühmeier)

Speaker (Franz Rundheber)

First Lady (Edith Haller)

Second Lady (Karine Deshayes)

Third Lady (Ekaterina Gubanova)

Papageno (Markus Werba)

Papagena (Martina Janková)

Monostatos (Burkhard Ulrich)

First Man in Armor (Simon O'Neill)

Second Man in Armor (Günther Groissböck)

First Priest (Franz Grundheber)

Second Priest (Xavier Mas)

Three Boys (Members of the Vienna Boys Choir)

Konzertvereinigung Wiener Staatsopernchor

Wiener Philharmoniker

Riccardo Muti (cond.)

Live performance, 30 July 2005, Grosses Festspielhaus, Salzburg

See Venice and then die

The 17 scenes in this opera, succeeding at a very tense pace, profited by the Liceu’s sophisticated machinery and lighting equipments to turn the whole into a motion picture, if one unrelated to Luchino Visconti’s award-winning masterpiece Morte a Venezia. Incidentally, the opera and the film share both the same year of first release (1973) and the ominous fame of swan songs of their respective creators, neither of these having survived 1976. At that time, the openly homoerotic charge of Thomas Mann’s original novel (1913) still worked as a stumbling block for mainstream opera-goers, but nowadays the coming-out of respectable old professor von Aschenbach is probably perceived as no big news and definitely not worth such a tragic punishment as death by cholera or, arguably, a “passive” suicide.

Guilt and punishment are such stuff as tragedy is made of. Since the shift in current morals caused feeling of guilt to disappear from the Western public discourse on homosexuality (even less so in Spain, where gay couples are legally allowed to marry), tragicism is no longer an option for staging Death in Venice. Thus director Willy Decker felt bound to pepper the story a bit by adding such hypes as Aschenbach kissing the boy Tadzio on a megascreen or desperately waltzing with him around the stage. True, all that happens as if in a dream, but when the agonizing scholar gets overwhelmed by a heap of naked male bodies choking him to death, one cannot help wondering how counter-heroically all that display of flesh can work, irrespective of the viewer’s sexual leanings. Let’s stop it here, lest both the director and this reviewer be exposed as homophobics in disguise…

The tribute to postmodern commonsense having been paid, Decker felt free to follow the libretto as literally as librettist Myfanwy Piper had done with Mann’s novel. His Venice is a disquieting city peopled by ruffians, gondoliers, porters, whores and peddlers of dubious goods and services, their faces and clothes painted with garish clown-like colors. The hollow cosmopolitan socialites assembling in the Grand Hôtel des Bains at the Lido are their victims, yet Aschenbach cannot sympathize with them either. All he is after is ideal beauty, whether in a Caravaggio painting on display at a museum or in Tadzio’s angelic face. In the end, both images morph in front of his eyes into one nightmarish obsession, while the Gods of Greece — Apollo and Bacchus — fight over his soul with contrasting messages from heaven, as in a mystery play. The sets are gorgeous, with blue skies recalling Magritte and pitch-black waters in realistic movie projections.

left: Uli Kirsch (Tadzio) [with Aschenbach’s Dopplegänger], right: Hans Schöpflin (Aschenbach)

left: Uli Kirsch (Tadzio) [with Aschenbach’s Dopplegänger], right: Hans Schöpflin (Aschenbach)

The same struggle between life and death breathed from the orchestral pit, mirroring the shifts of wind and tide from the iodine scent of the open sea to the heavy stench of the Lagoon in Summer and back — a common experience for Venice visitors, cleverly described in the libretto. Under Sebastian Weigle’s baton, the taxing score emerged in a glory of harmonies and colors: full-tone scales alternating with polytonalism, piano with Java-style gamelan and far-away echoes of the Baroque. Also the singing company was top-level. The German tenor Hans Schöpflin spun his exquisite mezza voce over the stream of inner monologues and extatic flourishes devised by Britten for his aging mate Peter Pears. Aschenbach’s protean opponent, tempter, flatterer, was the Texan baritone Scott Hendrick, always magnetic throughout his seven so diverse roles. Countertenor Carlos Mena, a reputed Baroque specialist, lent his sunny and mellow alto range to Apollo’s oracles. Within the swarm of cameo roles, particular praise was deserved by the sanguine Begoña Alberdi in the double bill of Strawberry Seller / Newspaper Seller, and by Leigh Melrose, a New Yorker, whose extended narrative solo as The English Clerk in the travel bureau (“In these last years/ The Asiatic cholera has spread/ from the Delta of the Ganges”) conveyed a thrill of Doomsday.

Carlo Vitali

Death in Venice, Act 2, sc. 10 (The strolling players)

Death in Venice, Act 2, sc. 10 (The strolling players)

A new co-production with Teatro Real, Madrid

Performance of 30 May 2008 product_id=Above: Waltraut Meier (Sieglinde), Plácido Domingo (Siegmund)

All photos © Antoni Bofill

June 9, 2008

Songs by Henry & William Lawes

Blaze sings with consummate control, impressive technical agility, a broad dynamic range and expressive flair; Kenny is his perfect accompanimental match, playing with flexibility, engaging adornment, dynamism, and unusual clarity of tone.

Many of the pieces here show the English response to continental progress, advances that travel, international marriages, publication, and the presence of foreign musicians at court would have made familiar. Italy’s new text-centered baroque aesthetic, defined in works like Caccini’s Le nuove musiche, found an English echo in expressive, songs with declamatory elements and Italianate ornamental idioms. Henry Lawes’ “A Tale Out of Anacreon” and “Amarillis by a Spring” or William Lawes’ “O Let Me Still and Silent Lie,” are fine examples of this Anglo-Italianism; the “aye me” of “O Let Me Still and Silent Lie” is as doleful as any madrigalistic ohime. Compositional tongue in cheek, in the song “In quell gelato core,” Henry Lawes went so far as to set the table of contents of an Italian song anthology, a convincing aria di piu parte with all Italian idioms and ornamentations “thereunto appertaining.”

The serious, impassioned Italianate songs are placed in counterpoint here with instrumental pieces—the broody and moody lute fantasia by Cuthbert Hely is especially notable—and strophic songs with triple meter dance elements like “O My Clarissa” or “Amidst the Myrtles as I Walk.” The performances of these songs are unflaggingly captivating, not least for the animating and beguiling use of the plucked strings. With harp, guitar, and theorbo all engaged, who can resist? Although historically it is the declamatory songs that have seemed most significant, in this anthology, I suspect it is these pieces that will most readily gratify, a pleasant reminder of the congeniality of the English ayre and the persistence of its tradition.

The saga of the Lawes brothers is one marked by sad poignance, for William lost his life in 1645, fighting for the royalist cause at the Battle of Chester. The concluding work on the recording is Henry’s “Pastoral Elegie to the memory of my deare Brother.” The text speaks of William’s ability to “allay the murmurs of the wind,” to “appease the sullen seas,” to “calme the fury of the mind.” The imagery here reminds of the Orpheus archetype certainly, but in more concrete terms, it underscores the dynamic power of musical expression. In the “Songs by Henry & William Lawes,” this is amply and wonderfully on display.

Steven Plank

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Lawes_songs.png

image_description=Songs by Henry & William Lawes

product=yes

product_title=Songs by Henry & William Lawes

product_by=Robin Blaze, countertenor; Elizabeth Kenny, lute and theorbo; with Rebecca Outram, soprano; Robert MacDonald, bass; William Carter, lute, guitar, and theorbo; Frances Kelly, double harp.

product_id=Hyperion CDA67589 [CD]

price=$21.99

product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/album.jsp?album_id=150297

Star Power in Paris “Capuleti”

No question that soprano Anna Netrebko is one of opera’s most visible, most glamorous, and most sought-after marquee names. And the French are positively nutty for mezzo Joyce DiDonato (the rest of the world is catching up) who has scored several (deserved) major career successes in the French capital. Small wonder then that there was a profusion of musical thrill seekers brandishing “je cherche billets” placards outside the sold-out Bastille house.

To get it out of the way up front (as it were): in spite of being five months pregnant, Ms. Netrebko was a radiant and wholly successful “Giulietta.” She was beautifully costumed in a flowing white gown to minimize the modest protrusion of a tummy, and she moved with her usual freedom and grace, including carefully assisted kneeling and fainting moments as required by the plot. Only when she was flat on her “dead” back did her condition become more apparent.

Her full-bodied, creamy lyric voice not only rang out thrillingly in the hall, but she commanded several breathtaking high-flying pianissimi as well. In her current “condition” it seemed that she may have divided up a few of the longer phrases to maintain breath control, but nowhere was this disturbing to the overall line. She nailed all of the familiar set pieces, and the audience responded with predictably enthusiastic ovations.