October 30, 2009

Tancredi by Opera Boston

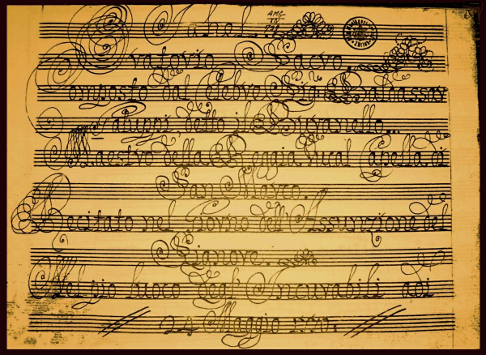

The sands were running out. It is in this light, perhaps, that we may view the opera that made his reputation throughout Italy: young man in a hurry to show off everything he can do in the way of melody, declamatory recitative, duets both pathetic and passionate, and one of those soon-to-be-world-renowned Act I “Rossini” finales. That Tancredi was the giant step may surprise modern audiences, for the opera is not a comic one — at least not intentionally. Tancredi is serious — even tragic, if the alternate “Ferrara” ending rediscovered by Philip Gossett is used, as it was by Opera Boston.

Rossini is best remembered as a composer of comic operas like L’Italiana in Algeri (four months after Tancredi) and Il Barbiere di Siviglia (three years later). But it isn’t just the stories that tag him: his music has a tendency to bubble, to froth, even when the direst matters are under discussion or depiction. His thunderstorms never threaten the levees, you can dance to his martial choruses, and as for pathos — that relies to a tremendous extent on the gifts of the individual singer. Rossini’s orchestra won’t tug your heartstrings all by itself — they are present to accompany, perhaps to sympathize, with the singing actors of his day, who prided themselves on the subtlety of feeling they could express. Composers who used too many instruments, too heavy and participatory an orchestra, were generally reviled in Italy as “Germanic.” You know — heavy metal thumpers like Mozart — but also, later, Meyerbeer, Weber, and even Verdi. If the orchestra takes the lead role, who is the prima donna here? Who is accompanying whom?

Rossini lived to see the taste change, and his great serious operas — Tancredi, Semiramide, Otello, L’Assedio di Corinto, Mosé in Egitto — all but forgotten. Singers forgot how to sing them and audiences forgot how to appreciate them. They have returned to favor in the last generation or two, a phenomenon led by dynamic mezzo-sopranos who could do what needs doing with a Rossini trouser role or pathetic heroine: Giulietta Simionato, Teresa Berganza, Marilyn Horne, Lucia Valentini-Terrani. Tancredi was one of Horne’s great roles, and it was she who brought back the forgotten tragic ending. (Rossini’s audience insisted that the hero survive, and there’s no particular reason he shouldn’t.) Today Horne’s successors include Cecilia Bartoli, Vivica Genaux, Joyce DiDonato and Ewa Podleś. Tancredi is especially identified with the latter, and Boston Opera staged it for her at the sumptuous, exquisitely restored Majestic Theatre, where any spectacle is sure to seem more of a treat.

Podleś is not a singer to everyone’s taste. Her voice is idiosyncratic to a degree, with a huge range from plummy low notes to a sturdy upper register, exceptional coloratura technique and sometimes imperfect line. The ranges break and re-break, there are melting legatos with growly interruptions. Her dramatic commitment, however, is total, and her use of her skills — and her flaws — is canny and entirely at the service of dramatic presentation. A tragic monologue by Podleś is never just a collection of notes but felt emotion in beautiful song. Her tone is shaded with doubt or anguish, her cascades of ornament underline passionate resolve. A Podleś performance is what bel canto is about, and she has a passionate following, out in force in the Boston performances. They were well rewarded.

As a stage figure, Podleś is matronly but in trouser parts she carries her weight in a way that seems masculine, not laughable. The Bostonians were only close to laughter at one point, when for the umpteenth time Tancredi muttered that no one had ever suffered as he was suffering — laughable since he was suffering only due to his inability to believe his lover had not betrayed him — and that was the librettist’s fault.

It was a star performance in a star part, and at 57 Podleś shows no sign of flagging powers. Her death scene in particular, nearly unaccompanied and quite startling for the era, was intensely theatrical.

The plot of Tancredi is drawn from a Voltaire tragedy; boiled down to libretto form, it is one of those tiresome stories based on a silly misunderstanding. If the heroine would only say, “But I didn’t send that (unaddressed) love letter to a Saracen; I wrote it to Tancredi,” everything might be cleared up. She never does say this, for reasons perhaps clearer in the play. True, Tancredi is in exile, proscribed as a traitor by those who fear his popular appeal, and to have written to him at all makes Amenaide a disobedient daughter and citizen. It might even endanger Tancredi, who, unrecognized, is back in town to fight the national (Saracen) enemy, and who also accepts (but why?) that the intercepted letter must have been written to another man — hence our lack of sympathy with his unreasonable suspicions. Why does Amendaide never speak? Because it would end the opera too soon? That’s not a good reason. She never offers us another.

With a story of this sort, the watchword for the director should surely be a Hippocratic: First, do no harm. You can’t make it make sense; the singers will do that (or they won’t). But don’t insert subplots that have nothing to do with the action — you will only raise questions that no one will ever answer. This is just what director Kristine McIntyre has done. She has decided Amenaide is pregnant out of wedlock, and presents this to us by having her stripped to her slip at the end of Act I. At this point everyone on stage is singing something, but no one refers to the pregnancy. Why show it if you’re not going to talk about it?

Either Tancredi has been sneaking home pretty often or the pregnancy has lasted several years — or else Amendaide really is sleeping around. These are questions Rossini never raised and therefore does not address. Tancredi wears no mask — why does no one recognize him if he was in town two months ago? If he made love to Amenaide, why is he so quick to believe her faithless? Why is the government willing to put her to death, though any Christian regime would surely spare a pregnant woman, at least until delivery? And why does her father forgive her, as no Sicilian father would in this or any other era?

McIntyre’s reasoning appears to have been that her soprano, Amanda Forsythe, really is pregnant. The rational response would be to put her in a larger costume and ignore it. Shazaam! No inane unanswered questions.

It is also clear why McIntyre set the piece in 1935 — nothing to do with political resonance (as she claims), but because the costumes are cheaper to procure than those of twelfth-century Sicily would be. She make think fascism in Italy between the world wars was an important issue — it is — but it’s not an issue Rossini ever addressed, and it does not explain how a Muslim army could be besieging Syracuse in the 1930s.

This was not a staging to inspire pleasure. The sets, too: ugly brick walls.

Amanda Forsythe, a popular presence in Boston’s opera scene, sang Amenaide. She has a very sweet, rounded soprano and ornaments elegantly, but her voice is quite small. The high points of the performance were her duets with Podleś, who gallantly scaled her own voice down to match Forsythe’s, so that we reveled by the minute in their deliciously twining phrases: bel canto heaven. Yeghishe Manucharyan, as Argirio, her unsympathetic father, displayed impressive skill at Rossini passagework in a thin, unattractive tenor. His sound was stronger in Act II, but not enough to make me eager to hear this voice again. DongWon Kim was impressive in the thankless role of villainous Orbazzano, and Victoria Avetisyan revealed a pleasing mezzo as Isaura, who has a “sherbet” aria in Act I. Sherbet arias were inserts, often written by some student or hack, and there is no reason to include them unless the singer justifies it. The second such aria was too much for its second comprimario. Conductor Gil Rose accompanied the vocal flights with welcome restraint, and the Act I finale built very nicely, but he didn’t draw a very impressive “Rossini crescendo” from his players during the overture.

A friend points out that none of the oversexed castrato or trousered female roles in opera ever do actually father a child, in or out of wedlock — that job is left to a tenor, baritone or bass. (One exception: Cherubino fathers a child — but we don’t find out about it until Beaumarchais’ sequel, La Mére Coupable, which was sort of made into an opera in Corigliano’s Ghosts of Versailles.) Opera lovers are cool with a woman singing of love to another treble voice, but shouting “Daddy!” to an alto parent evidently pushes the barrier. No doubt modern opera composers will update this convention in short order.

John Yohalem

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Tancredi_Ferrara.png image_description=Cartel del estreno de Tancredi (Rossini) en el Teatro Comunale de Ferrara en 1813 [Wikimedia Commons] product=yes product_title=G. Rossini: Tancredi product_by=Tancredi: Ewa Podleś; Amenaide: Amanda Forsythe; Argirio: Yeghishe Manucharyan; Orbazzano: DongWon Kim; Isaura: Victora Avetisyan. Opera Boston, at the Cutler Majestic Theatre. Conducted by Gil Rose. Performance of October 25.Verdi's ”Trilogy“ at Parma

Parma devotes the months to a major Festival, with other activities in nearby towns. Parma’s Verdi Festival aims at producing, by 2013, a boxed set of Teatro Regio DVDs with all Verdi’s operas in a special edition.

In Florence, the Teatro del Maggio Musicale Fiorentino produced “the big three” — Rigoletto, Il Trovatore and La Traviata — heard together on three successive nights. These were all entirely new productions by a young team, specialists in low cost but innovative work. This festival, a co-production with the elegant, classical Teatro Romolo Valli will continue in Reggio Emilio, “Verdi country”, but will not be heard in Parma.

Scene from Il Trovatore

Scene from Il Trovatore

Prices were quite low by European standards. The house was sold out in the

first week of bookings, proceeds reaching € 600.000, about two thirds of

the cost. As comparison, ticket sales in Italian houses cover, on average,

about 12% of production costs. Nearly 25% of the audience was made up of young

people under 26. Usually, the average of the audience is around 55 in Italian

opera houses. For many of them, it was the first time they’d been in an

opera house so they looked enthralled.

Ripa di Meana and his team (Edoardo Sanchi, set design, Silvia Aymonimo costumes, Guido Levi lighting). Guido Levi in charge of lighting.see the three operas as a single piece of musical theatre in three parts, viz. Rigoletto as a dark introduction in various shades of black and grey, Il Trovatore as a fantastic tragedy in blue and red, and La Traviata as a flowery dream.

This Rigoletto is “noir” rather than a dark introduction to the cycle. The entire plot is played in a bleak night. Very simple elements on the huge stage of the Teatro del Maggio Musicale:a movable wall squeezing the protagonists in a deadly tie, an oversized period car (a 1940s Buick?) where the Duke consummates his orgies, a small white doll house for Gilda, and old boat on the Mincio for the final scene. It is a tragedy without any glimmer of hope, not even in Caro Nome, or in the Love Duet.

Stefano Ranzani’s baton and the Maggio Musicale Orchestra (one of the very best orchestra in Italy for both opera and symphony ) were perfectly in line with this reading of the opera. Ranzani emphasizes the C flat and the D flat so that even the orchestra emanates a bleak color and atmosphere. Alberto Gazale was an excellent Rigoletto both dramatically and vocally and had a superb partner in Desirée Rancatore as Gilda; the opening night, (October 3rd), at the audience’s request, they had to encore the final scene of the second acts (“Sè, Vendetta, Tremenda, Vendetta”). It was harder to judge Gianluca Terranova who was called at the last moment to replace James Valenti as the Duke. He is a generous tenor, with an excellent acute and a strong volume, but uncertain phrasing — probably because he had to jump in the role without any rehearsal.

The following night Il Trovatore was played to a full house. On stage, there were no castles, no cloisters, no prisons, just a large early 20th century elegant living rooms with blue walls and a shocking red pyre (when required) or arches for the second act ‘s convent. However, the Count and Manrico (and their retinues) are in Medieval armour, whilst Eleonora, Azucena and the others in modern attire. The heightens the timeless reading of a plot where only Azucena is the character with psychological development. The others are stereotypes, almost a pretext for their arias, duets and concertatos. Some of the audience did not appreciated this interpretation of Il Trovatore, but at the end the applauses submerged the boos. Massimo Zanetti offered a carefully discreet conducting — in Il Trovatore the orchestra is mostly a support to the singers.

Scene from Il Trovatore

Scene from Il Trovatore

Juan Jesùs Rodrìguez, Anna Smirnova and Stuart Neill are well known serious, experienced professionals. Stuart Neill gave a vibrant high C at the end of “Di Quella Pira” without attempting to sustain it too long. The real surprise was the young Arkansas soprano Kristin Lewis; a true soprano assoluto with a very large extension, a pure emission, an excellent coloratura and the skill to go up quite naturally to the highest tonalities and go down, equally naturally, to the lowest. She lives in Vienna and sings mostly in Europe. It is easy to foresee that she will go far.

La Traviata had a single set: a large Art Nouveau living room with camellia flowers on the wall paper as well as in many vases and pots. Lighting provides various shades of green and of white on the walls. An oversize sofa dominates Violetta’s apartment in the first and third act; furnished in turn of the century style. The dreamy atmosphere is already in the introduction when Violetta is on stage longing for a bourgeois family life. But she really lives a Baudelaire’s environment where we nearly smell opium.

Conductor Daniele Callegari slowed the tempos gently — the performance lasts slightly longer than three hours, with two intermissions — in order to gently heighten the dreamy atmosphere.

Andrea Rost proved that her vocal instrument is still perfect even though quite a few years have elapsed since the seasons when she was the major star of La Scala . Her singing was passionate; she did not circumvent any of the traditional virtuoso, added (over the centuries) to Verdi’s original writing such as the B flat at the end of “Sempre Libera”. Saimir Pirgu is young (28 years old), and athletic. His Libiamo requires acrobatic skills. He is good looking; and his voice has thickened in the last couple of years. He is now a perfect Alfredo, especially for his tender phrasing. He should resist the temptation to take on tenore spinto roles, but he would be probably excellent in many Massenet and Gounod parts. Luca Salsi is a good Giorgio Germont but maybe too young for the role. It is not clear whether Saimir Pirgu’s Germont senior is just an old-fashioned Provincial country gentlemen or a hypocrite. Nonetheless, on a Sunday matinee, the audience was enthusiastic, applauding during the performance.

Giuseppe Pennisi

Production Staff and Cast

Franco Ripa di Meana, director. Edoardo Sanchi, sets. Silvia Aymonino, costumes. Guido Levi, lighting. Orchestra e Chorus del Maggio Musicale Fiorentino. Piero Monti, chorus master.

Rigoletto

Stefano Ranzani: conductor.

Gianluca Terranova:James Valenti; Shalva Mukeria: Il duca del Mantova; Alberto Gazale: Rigoletto; Désirée Rancatore: Gilda; Konstantin Gorny: Sparafucile; Chiara Fracasso: Maddalena; Giorgia Bertagni: Giovanna; Armando Caforio: Il Conte di Monterone; Roberto Accurso: Il Cavaliere Marullo; Luca Casalin: Matteo Borsa; Andrea Cortese: Il Conte di Ceprano; Miriam Artiaco: La Contessa di Ceprano; Vito Luciano Roberti: Usciere di corte; Elisa Luppi: Un paggio.

Il Trovatore

Massimo Zanetti: conductor.

Juan Jesús Rodríguez: Il Conte di Luna; Kristin Lewis: Leonora; Anna Smirnova: Azucena; Stuart Neill: Manrico; Rafal Siwek: Ferrando; Elena Borin: Ines; Cristiano Olivieri: Ruiz; Alessandro Luongo: Un vecchio zingaro; Fabio Bertella: Un messo.

La Traviata

Daniele Callegari: conductor.

Andrea Rost: Violetta Valéry; Milena Josipovic: Flora Bervoix; Sabrina Modena: Annina; Saimir Pirgu: Alfredo Germont; Luca Salsi: Giorgio Germont; Aldo Orsolini: Gastone; Francesco Verna: Il Barone Douphol; Gabriele Ribis: Il Marchese d’Obigny; Michele Bianchini: Il Dottor Grenvil; Leonardo Melani: Giuseppe; Salvatore Massei: Un domestico; Pietro Simone: Un commissionario.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/RIGOLETTOmmf01.gif image_description=Rigoletto at the Verdi Festival [Photo by Giuseppe Cabras/New Press Photo courtesy of Teatro del Maggio Musicale Fiorentino] product=yes product_title=Giuseppe Verdi: Rigoletto, Il Trovatore and La Traviata product_by=Verdi Festival, Parma product_id=Above: Rigoletto at the Verdi FestivalAll photos by Giuseppe Cabras/New Press Photo courtesy of Teatro del Maggio Musicale Fiorentino

October 29, 2009

Ned Rorem premiere at Oxford Lieder Festival

It’s strange that Rorem is relatively unknown outside the US, because there have been so many excellent recordings. There’s no excuse, Perhaps though this Oxford performance, by the Princes Consort, will put things right.

Evidence of Things Not Seen is a collection of 36 songs that flow together to form a whole greater than its parts. The first group of songs are optimistic, open ended. Rorem calls them “Beginnings”. “From whence cometh song?” is the very first line. The same questioning reappears throughout the cycle, expressed in Rorem’s characteristic rising and falling cadences.

“Middles” (the middle section) explores ideas more deeply, rather like development in symphonic form. There are some very strong songs here, such as ..I saw a mass, from John Woolman’s Journal. Woolman was a Quaker, and Quaker values infuse the whole 80 minute sequence. Indeed, the the title Evidence of Things Not Seen comes from William Penn. Rorem’s cadences are light quiet breathing, the way Quakers think things through in silent contemplation. Two songs to poems by Stephen Crane, The Candid Man and A Learned Man, provide counterpoint. The candid man blusters, using violence to impose his will.

Rorem chooses his texts carefully. Middles ends with a song to an 18th century hymn text by Thomas Ken which leads into Julien Green’s He thinks upon his Death. W H Auden jostles with Robert Frost, Colette with A E Housman. Mark Doty and Paul Monette write poems referring to AIDS. Jane Kenyon’s The Sick Wife poignantly describes a woman lost , still young, to some illness that keep her alive but barely sensate. In its own simple, direct way it connects to the final song, in which Penn reflects on the Bible. “For Death is no more than the Turning of us over from Time to Eternity”. Whatever the Evidence of Things Not Seen may be, following the journey in a performance as good as this is a moving experience.

The Oxford Lieder Festival often introduces performers and repertoire before they become mainstream. That’s why, for a small festival, it’s cutting edge, and one of the best ways to keep a finger on the pulse of what’s happening in song.

The Prince Consort

The Prince Consort

The Prince Consort are something of an Oxford Lieder discovery, although they have also appeared at the Wigmore Hall. This is a lively, flexible ensemble which brings together some of the most exciting young singers around. Many are already quite high profile — some have been heard at the Royal Opera House, Glyndebourne and Salzburg. They were represented tonight by the founder, the pianist Alisdair Hogarth, and the singers Anna Leese, Jennifer Johnston, Nicholas Mulroy and Jacques Imbrailo (a former Jette Parker artist).

Their fresh, vivacious approach suits Rorem’s music well. The Prince Consort have just released a recording of Rorem’s On an Echoing Road. on the audiophile label Linn. It’s good. That cycle includes many songs showing the influence of English composers like Ralph Vaughn Williams and Roger Quilter, so it’s a good choice for the English market. The audience at Oxford was sparse, perhaps because those who don’t know Rorem assume that if he’s modern and American they might not like him. But Rorem is steeped in the European tradition and was associated with poets like W H Auden. Perhaps now England will be aware how Rorem has rejuvenated the genre of English song.

Anne Ozorio

[Note: The recording Ned Rorem - On an echoing road by Prince Consort is available for download here.]

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Rorem16.gif imagedescription=Ned Rorem [Photo courtesy of The Ned Rorem Website]

product=yes producttitle=Ned Rorem: Evidence of Things Not Seen productby=The Prince Consort, Oxford Lieder Festival, Holywell Music Room, Oxford, England. 25th October 2009. product_id=Above: Ned Rorem [Photo courtesy of The Ned Rorem Website]

October 26, 2009

An Interview with Ileana Perez-Velazquez

Composer Ileana Perez-Velazquez was born and raised in the highly musical nation of Cuba, where she studied in Havana at the Escuela Nacional de Artes (high school) and the Instituto Superior de Artes (university-level). Later she took advanced degrees in music at Dartmouth and at Indiana University. She has a recent CD devoted to her work on the Albany label, and is presently a professor of music at Williams College in Massachusetts. We spoke on Sept. 11, 2009 via Skype.

TM: You were born in Cienfuegos, Cuba. Please tell me about your family, and about growing up there.

IP-V: My grandfather loved music, wasn’t a musician, but was connected to popular musicians from the Orquesta Aragon, which was famous in the fifties, sixties and seventies….

TM: It’s still famous.

IP-V: The Orquesta Aragon is actually from Cienfuegos. My grandfather had a business, a little food business, and the Orquesta Aragon used to rehearse next door. I had not been born yet. My grandfather became friends with them, and helped them when they were still unknown . They became very popular, and moved to Havana, where they had their career, and every time Rafael Lay and others visited Cienfuegos they would go to see him. My grandfather had strong connections with music, and loved it, but never studied it because he did not have the means. He wasn’t poor, but he couldn’t afford it.

He made my mother study piano, which she did for eight years, but she did not enjoy practicing. She didn’t want to be a professional musician, but she would play piano every afternoon at home. During the first two years of my life, she was playing, and I was totally in love with it. By the age of three I was sitting on top of the piano while she was playing, trying to learn something.

They had a deep influence on me in my early years. When I was learning my first pieces, my grandfather would sit down with me, and listen, and try to put some emotion in my playing, even if he didn’t know musically what he was talking about.

TM: What kind of music was your mother playing — classical, popular?

IP-V: Classical, although she also enjoyed playing from the Emilio Grenet compilation of Cuban popular music. When Orquesta Aragon moved to Havana, my grandfather was friends with Orquesta Los Naranjos in Cienfuegos, who were popular musicians, and once in a while my grandfather took me there to see them play. I had that popular influence, and classical influence from my mother.

TM: How far is Cienfuegos from Havana?

IP-V: These days it is three hours drive. It is a town in the south of the island, and it is absolutely beautiful with sea all the way around, inside a bay. The name means “One Hundred Fires”. It is not a small town, but it is not a big city either. In the fifties there was a very strong “Pro Musica” organization there supporting classical music. If you look at the number of musicians from Cuba at that time it is very impressive for a small island. My main composition teacher was Carlos Fariñas, who was also from Cienfuegos.

At any rate, when I was a child the trip from Cienfuegos to Havana was six or seven hours. There was no main highway through the island — everything was little back roads, and it would take forever to get to Havana when I was a child.

TM: A provincial town.

IP-V: Very much so. It is different now — I was there last August — but it is still provincial.

TM: How was it affected by the Revolution?

IP-V: Just as was the case everywhere in Cuba, a lot of people left in the early 1960s — well, not a lot, but those who were wealthy and were intimidated by the Revolution. It’s hard for me to say, since I was born after the Revolution, in 1964, and the Revolution was in 1959. What I remember was that my grandfather did not like the Revolution, and my father did, living in the same house. Luckily, my father was a very respectful man, and so would not argue with my grandfather.

My grandfather lost his business, because the Revolution nationalized everything. He was unhappy, because he had worked all his life building his small business, and then it was taken away. On the other hand, my father came from a very poor family that had nothing, and so he was very happy about it. The Revolution meant that my father could get an education, and go to the university. After graduating as an engineer, he died, when he was only thirty-seven years old. I was fourteen at the time.

To go back to your question, the Revolution affected people in an emotional way. Within the same family you could see people who had different opinions. Cubans are always passionate about their opinions, and get very emotional very quickly.

TM: Perhaps the Revolution did not have such an effect on the musical scene in Cienfuegos?

IP-V: The Revolution created a music school for children in Cienfuegos which I attended from the age of six on. It was a small school, but with good teachers. There was an excellent pianist, my teacher there, who had studied in Havana, and was very well-regarded, and she had happened to move back to Cienfuegos. She played beautifully. I still remember her playing the Revolutionary Etude of Chopin — very fast, very intense — she was a very good pianist.

TM: What was her name?

IP-V: Mercedita.

TM: Where did your family come from?

IP-V: On my mother’s side, my grandfather, who had the store, had come from the Canaries — not him, but his parents. His wife, my maternal grandmother, was one hundred percent Spanish, but I can’t say from what part of Spain, because they had been in Cuba for generations. She grew up among people who had supported the Cuban revolution against Spain. The woman who raised my grandmother, her aunt, was this amazing woman who was good friends with Máximo Gomez [1836-1905] and some of the important historical figures of the revolution. I grew up hearing all sorts of interesting stories about her bravery — she would go to a Spanish party dressed like the Cuban flag. That taught me that women could do a lot — she was an influence that showed me that I could do something with my life.

On my father’s side everything is less clear, because my father’s father also died very young — both of them died from cancer. Just a few months ago I asked my mother “Who was this guy, my grandfather?” He was a gallego, from Spain, from Galicia. My father’s mother was probably a Cuban for generations — I don’t really know.

I might have mulato ancestry on my father’s side, but I don’t know for sure.

TM: Not so unusual in the Caribbean.

IP-V: No, because we are a mixture of so many things. My sisters have blue-green eyes and dirty-blond hair, and I am nothing like that, although we are 100 percent sisters. Physically I don’t look anything like them. They take after the gallego man who was my grandfather.

TM: Were you brought up in a Catholic family? Was there a presence of the Church?

IP-V: That’s a very good question. My grandmother was Catholic — very much so, and on my mother’s side, they kept all their Catholic saints in the house, but because of the Revolution they could not go to church, because of repression against the church during the first twenty years of the Revolution — not physical repression, but if somebody wanted to go to the university, and he was a religious person, it would be more difficult to get in, because they thought it wasn’t a good thing. My grandparents were going to take me to be baptized, and when my father came in he was very upset and said that it wasn’t a good thing to be baptized, and so I was never baptized. But I was always curious about the church — I would go and look, but I wouldn’t go in.

That is something I have in common with many Cubans of my generation. A lot of Cubans ended up going to church later on. One of my sisters goes to church, and so does my mother. With the visit of John Paul II in the nineties things changed dramatically.

TM: Your mother played piano. Did you get started in music with piano?

IP-V: Yes. I studied piano all the way through to my college years at ISA — Instituto Superior de Artes. When I was there I was a double major in piano and composition. I practiced six hours a day, and performed the Stravinsky concerto. I like playing contemporary music — Stravinsky, Bartok — but I also like playing Scriabin, Chopin, Bach. I know the piano repertoire very well because I played a lot of it.

I started playing Bach when I was very little — Mozart, Beethoven, everything. I played mostly classical music, although I also played the music of Cuban classical composers, which in the last two centuries has been influenced by some elements of Cuban popular music such as rhythm and timbre.

TM: You went from Cienfuegos to Havana.

IP-V: From third to sixth grade I was studying in Cienfuegos. When I was eleven my father decided that if I were to be a serious musician I needed to study somewhere where there was a more serious school of music. In Cienfuegos I had a very good piano teacher, and very good solfege and ear training, but they only had instructors for four instruments. So I went to Santa Clara, which is north of Cienfuegos. At the time it was two hours drive. So by eleven I was no longer living at home, because I wanted to get a better education.

My father was studying at the university in Santa Clara, and I was studying at the school of music there. He was at a dorm, and I was at another, so he would visit me a couple of times a week, and I would go back home once a month. I studied there in seventh, eighth and ninth grade.

When I finished ninth grade there was a national competition in Cuba for admission to the national school of arts. I went to Havana for the audition, and was selected to continue in Havana.

At fourteen I started at ENA — the Escuela Nacional de Artes. Later the name was changed to the Escuela Nacional de Música. This is a school that is equivalent to high school level in the United States, but a school that is totally focused on music, a Conservatory. We did not study the sciences, but very deeply in music, literature, and history. My science background for electronic music I had to do on my own, later. That was a challenge!

After four years there I started at the Instituto Superior de Artes. Here people often start studying music in college, but there are no master’s or doctoral degrees in music in Cuba. We have music education at an earlier age.

TM: What was the musical environment like in Havana? Did you hear international popular music from abroad? A composer from Argentina or Brazil in the seventies or eighties might have heard Chick Corea or Yes or the Beatles. What did you hear in Cuba?

IP-V: People in the Communist Party would say that these influences were negative, so they were very much prohibited. People listening to this music were doing so illegally. I was exposed to it because I was at music school, and my friends would have recordings, but at home I couldn’t listen to it — my father would get upset. In that sense it was lucky that I wasn’t at home, so I could hear some. I did not hear as much as I would have liked to, but I did have some sense that those things existed.

Havana is more open. When I was in Cienfuegos and Santa Clara there was more of a small-town mentality. They were not open to anything like that — it was not supporting the Revolution. The artists and intellectuals lived in Havana so that made things more accessible. When I was at the Escuela Nacional de Artes I was exposed to jazz, the Beatles, and all of that. Again, not as much as I would have liked. Some of my friends would play jazz.

TM: What contemporary classical music did you play, did you hear in Havana?

IP-V: I had a wonderful group of friends in Havana who loved contemporary music. After school was over, starting at 10 PM, we would get together, and play all kinds of contemporary music. I had a friend, who also became a composer — she is now in Spain — Fernando Rodriguez. He became the president of this club. It was called the Club Federico Smith, with members a few years older than me — I was the little girl joining the group. We would stay up until 2 AM listening to “From the Canyons to the Stars” — pieces that the school didn’t play for us - the recordings probably came from Federico Smith, an American in Cuba, who had died — all kinds of contemporary music. We did not have the scores for a profound analysis of these works but I was exposed to a lot when I was fourteen.

I also read so much literature. All my grounding in poetry comes from those years. At the same time I was playing classical music on the piano, playing chamber music, singing in choirs.

Here anybody had a tape recorder — but in Cuba, oh no. Only a few had tape recorders to play anything. Not me. My family had nothing. My father had died by that point, and I had almost no money. All I had to survive at that point was the food that they put on my plate in the dormitory where I lived, and ten Cuban pesos a month which my mother would send, which was equivalent to almost nothing. So I had no way of having access to information not offered at school unless a friend liked me and shared it with me. I am not complaining because I had good teachers of classical music at school.

TM: When did you start to compose? What inspired you?

IP-V: I was always interested. At eleven I started writing little things, but I started in earnest at the school at fifteen with my teacher of harmony, who was a composer himself. His name was Enrique Berver. He had lived and studied in Paris for quite a few years, and had awareness of contemporary harmony. He would take me to his house and show me techniques that he did not present in class. And he told me I had talent. And I was like….Nobody would tell me that. Who was I? Nobody. When I was fifteen, all by myself, in the middle of Havana, with all these people. He was very encouraging.

I started, like anybody would, making short piano pieces, and then I got really into it. I loved it. I had always loved it, but before that there had not been anyone to say “Go ahead and do it!”

That’s important. I have a three-year old now, and as he grows, if I feel that he has the talent I will say “do it!”. A little person needs some support.

TM: What was the music that inspired you. You mentioned Messiaen. What else grabbed you?

IP-V: Stravinsky, Bartok — I totally loved Scriabin. Villa-Lobos, from Brazil. I loved Piazzolla. I wrote a piano trio with influences from Piazzolla in the second movement. Obviously it doesn’t really sound like Piazolla. Now I am more interested in other things, but I still recognize his value.

TM: With whom did you study composition at ISA?

IP-V: Carlos Fariñas. He was a great teacher. When I first came, I always had all these ideas, and they would change dramatically, very quickly — that’s my personality. He taught me that music needs time to convey the message. You need time to develop the motive so that it can later change into something else. He was trying to put some rigor into the way that I approached my compositions. He taught me skills. There came a time when I was ready for more, but he was still that way, but I am very grateful to have studied with him in my early years.

TM: What was his pedagogical background? Did he teach serial technique?

IP-V: He was very open-minded, and did not push any esthetics on me. I studied serialism, but never wrote serial pieces. I have never written serialism, and am not interested in doing that any time soon. [Laughs]. Maybe never!!! Of course I respect the value of it, but I never had to do it. I have heard that in the USA they forced students to do that in academia.

I was lucky I never had to go through it. I had it as homework, and I did my assignments, but it was not my creative work.

We were encouraged to find our own voices, a way to express ourselves. We didn’t have to follow a particular international school, where people said “This is what we should be doing”.

TM: In Brazil, which has some cultural similarities with Cuba, as a mulato country with a strong musical culture, composers consciously consider what there is that is Brazilian in their music. Is there a tension between writing music that is contemporary and music that is Cuban? Is this something that is important for you?

IP-V: It is — it’s still important for me. I don’t have to challenge myself to do it. I think it comes naturally.

TM: Anything you write is Cuban.

IP-V: It’s not Cuban in the traditional sense. A Cuban might say “Who says that’s Cuban”? A person from the street, with no musical background, would not see the connections, because they are not clear, but I think they are there.

In the seventies, when I was growing up, Cuba was closed to foreign influences, and none of that music would be playing on the TV or radio. We did not have an invasion of pop, as you did in other countries, where the industry came and took over, and quashed the authentic local music. They could not do that with Brazil, whose music is so beautiful and so strong.

We started to have that challenge in the eighties and the nineties, but I left in 1993. Now, when I go there, I see people doing hip hop mixed with salsa. Unfortunately I don’t like hip hop…I can see its value, but musically it doesn’t capture my attention.

In Cuba we were lucky to have intellectuals who were able to write a document to convince the government that we should be able to play contemporary music, for example. In Russia, the composers had to write for the people. In Cuba I could write my contemporary music, and we had international contemporary music festivals every year. Now, playing American music on the street was something else again. They didn’t want that.

With respect to being a Cuban composer, I can think of a friend who does this more intentionally than I do. My friend will actually take material from folk music, and work with these elements, so that they are more obviously present.

My music is different, because I try to avoid the repetitive patterns that are characteristic of folk music. It’s not that I don’t like folk music, but that folk music is there, and so strong, and so beautiful, and so wonderful. Why would I need to rewrite it again? It already exists. I am trying to do something that is my own, something that I would say is more creative, but I don’t want to offend anybody, so I will say something that is more able to express myself, rather than taking repetitive rhythmic and/or melodic patterns from folk music and throwing it into my music.

TM: You finished your bachelor’s in 1987, and came to do a masters’ in the US in 1993.

IP-V: In between I was in Bogotá, Colombia. In 1990 I decided that I needed to go outside Cuba. In 1988 I won first prize in a young people’s festival in Cuba, and the prize was to go to Hungary to the Bartok Festival. In 1990 I went back and met Ligeti. He seemed to like what I presented, and wrote a letter of reference for me. I couldn’t study with him, because by then he had already stopped teaching. He mentioned Donatoni. I wrote to Donatoni, who said he would be happy to have me as a student, but that I would need to find a scholarship, and of course Cuban money had no value outside Cuba, and I did not have any connections in Italy.

The next year, in 1991, there was an international electronic music festival, and Jon Appleton came. He heard my music, and offered me a scholarship to study at Dartmouth. I said “Great!” because I needed to go out and learn more, especially in the area of electronic music, because I had learned a lot about acoustic music, but we did not have much experience with electronic music because of lack of resources and information. Technology requires money.

I went to the US Embassy, but never got a visa, and ended up going to Colombia, where I taught at the national university, and helped to organize a festival to which we invited Jon Appleton. I suggested to them that they invite him, and luckily they listened to me. Jon went personally with me to the US Embassy, and finally I got the visa after two years, and came here to study in 1993. It was a long story.

TM: And Dartmouth was very different from Cuba.

IP-V: My goodness.

TM: Very cold.

IP-V: I will never forget the snow all the way up to my knees. Every night I would leave the studio at 1 AM after I had finished my work.

TM: And a long way from any city.

IP-V: Coming from Havana, and Bogotá, and going to Dartmouth, was like “Oh my God, what did I do with my life???” But just I worked intensively for two years, and then it was over. It was a cultural shock, too. People are very different, the weather is different…everything was different. People, instead of talking to each, would send emails. That was a shock. They were in the same room, and they would send emails to each other. And I thought “What’s wrong with these people? They don’t talk, or what?”

It was a cultural shock — it’s not so bad now, but it took me a while.

TM: You went from there to Indiana.

IP-V: After two years of one-hundred percent focus on electronic music, I wanted to do acoustic music.

TM: People I knew at Princeton referred to these as silicon- and carbon-based music.

IP-V: That’s right. I thought “Give me some instruments now! I need to write for instruments again.” Indiana also has a Latin-American Music Center, with Carmen Tellez there, and all her friends — it was a group of Latino people with whom I thought I would feel more connected from the human point of view.

TM: Please talk about the works on your CD [“an enchanted being, salty waters, and infinite stones”, Albany TROY 987], which has a variety of different ensembles. I thought the titles were quite interesting.

IP-V: I love poetry — when I have the time I write some poetry.

TM: For examples, Duendes alados [Winged sprites].

IP-V: Don’t ask me where it came from, because it’s from my imagination. Duendes are magical creatures, and with wings they are even more magical.

TM: When people write string quartets, they tend to think of abstract music — Beethoven, Bartok — but they don’t think of winged sprites.

IP-V: I didn’t mean to write a “serious” string quartet. In fact, I didn’t call it “String Quartet” — it’s just a series of pieces. Of course the four movements are part of one composition, but I never intended it to be a “great string quartet” in the serious classical way.

TM: Which is perhaps liberating as you are writing it.

IP-V: Exactly. It made me have fun in writing the music, and that’s what composition should be — something that we enjoy, not just when it is performed, but the process of composing the music. It’s not a party, but it’s enjoyable in the sense that it is satisfying, and we can enjoy the entire process, as opposed to having the painful obligation of writing something great.

TM: Was it a commission by the performers?

IP-V: By the Hopkins Center at Dartmouth, which has a series of commissions. Originally it was to be a percussion quartet, for the Amadinda Quartet, but I got a letter saying that Amadinda had dissolved, and that now it would be a string quartet! How do I go from a percussion quartet to a string quartet! I was happy to do it, and that’s how it came out.

TM: Some pieces have titles in English, and some in Spanish. Is there a reason for that?

IP-V: Our Sacred Space is in English, because it is a quote from a Buddhist who wrote in English, who said that we are always at the center of the universe, and we can always feel that we are in our sacred space. In other cases, sometimes it sounds beautiful in English, sometimes in Spanish

TM: Please talk about Encantamiento, with Sally Pinkas. She is an exceptional pianist….

IP-V: And a great friend. She is a lovely person. There is actually a new version of Encantamiento out by Pola Baytelman on a CD which she will release on Albany this year [released May 2009, TROY 1116] . It sounds like a different piece. I like both. The Baytelman version is slower in pace, but the polyrhythmia is so intense. Sally’s is brilliant technically because it goes faster, but perhaps the polyrhythms are not as clear….I love both versions — it is amazing that talented performers can do this with one’s music.

TM: Please say a little about Un ser encantado.

IP-V: That’s an older piece. I wrote it while I was still at Indiana. The poetic images from the titles of each movement are what I was thinking about in writing the piece. At the time I was very interested in timbre, so there is a lot of exploration of the sounds of the percussion instruments, mixed with the sound of the piano in such a way as to make an atmosphere that sometimes is transparent and sometimes heavier and more percussive.

It’s full of rhythmic contrasts.

TM: There seems to be a narrative focus to the works on your CD. This is often something that helps to make electroacoustic music work, since rather than being tied to instrumental techniques and motives, it can be more pictorial and cinematic.

IP-V: I think it is easier for the audience to perceive the piece that way, because especially if a piece is for tape, it is harder to make a connection with whatever is going on an empty stage. If there are just two loudspeakers there, and that is all, they have to close their eyes, and try to imagine what is going on. In both cases, titles are very important, because a title can help the imagination of a person who is listening to a work.

TM: Do you continue to work with both tape and instrumental music?

IP-V: I intend to do so. In recent years I have received commissions from ensembles who want to perform my music. Right now I am writing an acoustic piece for Continuum, but after that I want to write a piece for percussion and electronics for a wonderful percussionist here [at Willliams College].

Acoustic music, in my opinion, is more likely to be preserved forever, if it is good music. We have a heritage of centuries of music, so to produce something that is likely to last, it has to be more than excellent. But, so what! I will take the challenge.

But if I play the electronic music of the sixties to my students they say “it sounds like a really old synthesizer. Those sounds are not interesting anymore. I don’t like it.” They feel no connection because the technology has evolved tremendously since then. This is a challenge that electronic music faces from the passage of time. But if I play a Bartok quartet, the students still think it is the greatest. But for electronic music, even ten years makes a difference. In the eighties frequency modulation sounds were used, but nobody wants to hear that anymore. There are one or two pieces that are references, but only in classes, because they are not heard in concerts. This is a big challenge.

So, yes, I am interested in continuing to work in the field, but I am very aware of the challenges involved.

TM: Do you have another CD of your works in the pipeline?

IP-V: I have a couple of pieces in mind. At the moment there will be a piece of mine for mezzo and piano on an anthology of works by Cuban composers — Tania Leon, Sergio Barroso, Orlando Jacinto Garcia which will be released by Innova [scheduled for fall 2009].

TM: Please talk about your vocal works — songs, dramatic works.

IP-V: Nanahual, with two versions, one for soprano, one for mezzo. The original was for soprano, but a mezzo asked me for a version, and it turned out that the one which was recorded was the mezzo version. For that piece I wrote the poetry myself, based on Nahuatl legend.

After that I wrote a piece for Aguava New Music Ensemble, based on texts by Rabindranath Tagore, Like the subtle wings of love. Presently I am working an piece for soprano, and four instruments — violin, cello, clarinet, and piano, using poetry from a young Cuban poet who is now in Miami — Carlos Pintado, an emerging poet. I found his poetry to be expressive and beautiful.

I actually wrote an opera very early on, at ISA, but it has never been performed, and since so much time has passed, I would have to review it before it went before the public.

TM: What was the title?

IP-V: I called it Inmanencia. It is based on a Latin American legend, in a poetic version by a friend. Very poetic and full of symbols.

TM: A one-act opera?

IP-V: Yes.

TM: What is your next big project?

IP-V: I take my life one day at a time. I like writing music that I know is going to be performed, and of course it is harder to get good and multiple performances of music for orchestra and large ensembles.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Ileana.png image_description=Ileana Perez-Velazquez product=yes product_title=An Interview with Ileana Perez-VelazquezThe Turn of the Screw at ENO

‘You see, I’m bad, aren’t I?’ declares Miles, teasingly, at the end of Act 1. Indeed. The ‘evil’ which James desires that his readers should merely ‘imagine’ is unambiguously paraded before our eyes by McVicar: the children romp riotously in a frenzied nursery scene; Quint glints malevolently from the Tower, and brazenly challenges a hysterical Governess; Miss Jessel wails with bitter fury, grasping at Flora in a desperate bid for Quint’s attention; the Governess rampantly suffocates the children she professes to protect.

Cheryl Barker (as Miss Jessel a former governess) and Nazan Fikret (as Flora)

Cheryl Barker (as Miss Jessel a former governess) and Nazan Fikret (as Flora)

The dimly-lit stage suggests first the cold, charmless recesses of Bly, then

the eerie expanse of the gardens and lake, as filmy, translucent screens

shimmer back and forth, brushed evocatively by Adam Silverman’s subtle

lighting. The occasional gleam glances on an iron bedstead, an ancient piano, a

painted rocking horse, as McVicar assembles an authentically Victorian domestic

world, faithfully to James’ original setting. In the shadows, servants

scurry back and forth, their reflections caught in the rolling panes, hinting

at other presences and snatched visions. Aware of the critical debates

concerning James’ ambiguous novella, Britten declared that he wanted

‘real’ ghosts singing ‘real’ music – no symbolic

groaning and shrieking! – but, one might argue that in this production

the ghosts are in fact all too real: despite the presence of the sleeping

Governess during their Act 2 Colloquy, these are genuine physical beings, not

imagined phantoms or indefinite apparitions.

In this unequivocally corrupted world, Mrs Grose is certainly right to fear for the safety of her charges, Flora and Miles. And this was a magnificent performance by Dame Anne Murray, whose lyrical, eloquent cries convincingly conveyed the housekeeper’s heartfelt anxiety, motherly love and tremulous fear for the children’s welfare. In the ‘Letter Scene’, Murray’s clear, focused lines powerfully demonstrated her genuine concern when Miles is dismissed from his school; although the appearance of Quint’s uncanny celeste motif hints at the cause of Miles disgrace, Murray’s outpouring of relief that the Governess shares her faith that Miles cannot be truly ‘bad’ was truly touching.

Despite rather woolly diction, the Welsh soprano Rebecca Evans went from strength to strength as the performance progressed. The occasional ‘catch’ in the voice was evident in the opening scene, marring for example her telling line ‘O why did I come?’; but as her confidence grew she produced some beautiful, floating curves in the upper register, subtly lingering, abstractedly, and perfectly conveying the deluded romanticism of a dreamer whose unworldliness proves more dangerous than the actual horrors she imagines. Transfigured by a single beam of light, Evans’ final, chilling wail, over the body of the dead Miles was both poignant and emotionally piercing.

Cheryl Barker (as Miss Jessel a former governess), Rebecca Evans (as The Governess), Nazan Fikret (as Flora) and Ann Murray (as Mrs Grose the housekeeper)

Cheryl Barker (as Miss Jessel a former governess), Rebecca Evans (as The Governess), Nazan Fikret (as Flora) and Ann Murray (as Mrs Grose the housekeeper)

The dual role of the Narrator/Quint was performed by tenor Michael Colvin. He projected well in the Prologue, carelessly flickering through the pages of the manuscript which holds that tale, his confident, warm voice aptly conveying the nonchalance, bordering on neglect, of the handsome guardian, and also foreshadowing the seductive charm of Peter Quint himself. Quint’s first vocal utterance, his unearthly nocturnal appeal in Scene 8, ‘At Night’, slyly crept in, oozing bitter-sweet charm and building to a commanding, hypnotic plea. However, Colvin did not always capture vocally either the pernicious seductiveness or menacing malevolence of the presumptuous valet. Certainly his actions leave little room for doubt: he whips the bed clothes from the sleeping boy’s bed, lures and urges him to embrace ‘freedom’. But, it was not until the Act 2 battle between Quint and the Governess that Colvin captured the truly forceful note of desperate evil as he implored Miles to steal the letter. Cheryl Barker, as Miss Jessel, was equally compelling: she avoided overstatement and dramatic extremes, balancing menace with lyricism, indicative both of her spurned love for Quint and her despair at his betrayal.

Completing a superb cast, Charlie Manton as Miles and Nazan Fikret as Flora were outstanding, never overshadowed or out-sung by their professional partners. Manton’s Miles was certainly a match for any of the adults: effortlessly evading their attempts to constrain and curtail his burgeoning individuality and maturity. His ‘Malo song’ was beautiful in its innocence and purity, the intonation perfect and the words delivered with unaffected clarity, as the cor anglais twined sinuously around the haunting melody. And, the Act II piano-playing scene was expertly pulled off, as the precocious young boy convincingly mimed his way through an increasingly piquant sequence of piano pieces, thereby distracting his guardians and liberating Flora to flee to the arms of Miss Jessel. A final-year undergraduate at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, Nazan Fikret is an experienced in this role, which she first sang aged twelve, and her confidence and accuracy suggest a promising talent.

Returning to conduct The Turn of the Screw in London for the first time since 1956, Sir Charles Mackerras created unstoppable musico-dramatic momentum in the pit, the sliding screens allowing him to maintain the expressive tension in the instrumental interludes, as each scene merged seamlessly into the next. This was both powerful ensemble work and impressive solo playing. Every colour and nuance was presented with precision and force; indeed, one would scarcely guess that there were only 13 players in the pit - the timpani outbursts were spine-shuddering. A curtain call presentation by current Music Director Ed Gardner to Mackerras acknowledged the latter’s achievement over 61 years, at this theatre and internationally; clearly there are no signs of a diminishing of the conductor’s dramatic insight or musical energy.

Britten’s opera is essentially an ‘intimate’, even private, work: 16 short scenes interspersed with tightly twisting instrumental variations enact a psychological drama presented by just 6 soloists accompanied by only 13 instrumentalists. Yet together, McVicar and Mackerras argued persuasively that the horrors and fears that this Jamesian tale reveals are vast and threaten us all.

Claire Seymour

image=http://www.operatoday.com/the_turn_of_the_screw010.png image_description=Cheryl Barker (as Miss Jessel a former governess) and Michael Colvin (as Peter Quint a former man-servant) [Photo by Clive Barda courtesy of the English National Opera] product=yes product_title=Benjamin Britten: The Turn of the Screw product_by=Governess: Rebecca Evans; Mrs Grose: Ann Murray; Peter Quint/Narrator: Michael Colvin; Miss Jessel: Cheryl Barker; Flora: Nazan Fikret; Miles: Charlie Manton. Director: David McVicar. Conductor: Sir Charles Mackerras. English National Opera, London Coliseum. Thursday 22nd October 2009. product_id=Above: Cheryl Barker (as Miss Jessel a former governess) and Michael Colvin (as Peter Quint a former man-servant)All photos by Clive Barda courtesy of the English National Opera

Ravel and L’Heure Espagnole at Covent Garden

Yet this is not an evening of dark cynicism: John MacFarlane’s front cloths for Ravel’s L'Heure Espagnole and Puccini’s Gianni Schicchi for — a glimpse of busty cleavage, enticing coils of pasta — signal that it’s earthly pleasure and not divine punishment which is centre stage in these witty, delightful productions.

Macfarlane’s set for Ravel’s one-act gem is inspired. Frustrated by her husband’s prim devotion to his business affairs, and longing for more action in the boudoir, Concepcion, the frisky wife of the town clockmaker, Torquemada, is literally confined in the false proscenium. There are many clever touches; as when the embossed rose wallpaper and rich curtains are slyly transformed by Mimi Jordan Sherin’s slick lighting from shop décor to bedroom draperies. Torquemada’s weekly maintenance tour of the civic clocks offers Concepcion her sole hour of freedom, and the passionate poet, Gonzalve, is quick to take advantage. But, on this occasion, Torquemada has ordered Ramiro, a muleteer, to wait in the shop. The overwhelming number of ticking clock faces reminds us of just how little time Concepcion has to enact her plan, adding a tinge of hysteria to the frantic mood. And, there is plenty of opportunity for farce and slapstick, as first Gonzalve and then a second admirer, the banker Don Inigo Gomez, hide in the clocks, while Concepcion decides to spurn both, in favour of the brawny Ramiro.

The characters are parodies worthy of commedia dell’arte — the bloated banker, the idealist poet, the gullible youth, the frustrated housewife — and they are clothed in suitably garish costumes by Nicky Gillibrand. The Romanian soprano, Ruxandra Donose, is impressive as the aptly named Concepcion, fully convincing as she grows ever-more frustrated and desperate, and singing with superb projection. As the muscular muleteer, Ramiro, Christopher Maltman’s bright, golden sound is perfect. Maltman bounds with puppyish energy, happily heaving and twirling grandfather clocks at Concepcion’s whim, and showing both heft and lyricism in this detailed interpretation of the role. The hapless poet, Gonzalve, is sung by the French tenor, Yann Beuron, whose warm, passionate tone conjures a suitably dreamy air; Andrew Shore delivers a typically witty and well-timed cameo as the blustering Gomez.

Ravel’s score is rich and ravishing, almost too sophisticated for the ribald tale it illuminates. Pappano paced it perfectly, allowing us to appreciate how deftly Ravel eases between genres — here the lilt of a pasodoble, now a jazzy syncopation, next a pulsing habanera. Ravel is just as capable of musical irony as Les Six, and just as adept at pastiche and parody as Stravinsky. This is a dense, detailed score, with castanets, tambour de basque and sarrusophone supplementing just a few of the sounds supplementing the large orchestral forces. Drawing exquisitely refined playing from the ROH orchestra, Pappano reined in the forces at his disposal, never overwhelming his singers, while allowing the details to serve the stage incident.

A chorus of show-girls joins the cast for the final number on lust and love, the dazzling glitz and glamour both darkly ironic and lushly entertaining: we heed the moral, while relishing the rollick.

Maria Bengtsson as Lauretta and Thomas Allen as Gianni Schicchi

Maria Bengtsson as Lauretta and Thomas Allen as Gianni Schicchi

Long overshadowed by its tragic partners in Puccini’s triptych Il

Trittico, Gianni Schicci is a delicious satire on avarice. Buoso

Donati’s death prompts an anxious search by his presumptuous but

down-at-heel family for his will: locating it, Rinuccio demands permission to

marry the peasant girl, Lauretta, in exchange for handing it to his aunt, Zita.

All are distraught to discover that Buoso has left his fortune to a monastery,

but Rinuccio assures them that there is someone who can help — Gianni

Schicchi, Lauretta’s father. Impersonating first a doctor who declares

Buoso revived, and then Buoso himself, Schicci conjures a plan to ensure his

and the lovers’ future wealth and happiness, while the Donatis make

greedy grabs for their inheritance, torn between their avarice and their social

pretensions.

Jones gives us quite a dark reading of this score: the grimy, drab 1950s décor, complete with peeling wallpaper, broken television set and rusting radiators, certainly enhances the Donatis’ mood of desperation. The large cast, including children and farceurs, are expertly choreographed throughout, in an astoundingly detailed, meticulous staging which demonstrates both imagination and an intelligent responsiveness to Puccini’s score. Not a movement, gesture or facial expression is misplaced: manic it certainly is, but never messy.

The cast are uniformly superb — a convincing portrait of collective greed. Yet each character is fully individualised through gesture. This revival featured many of the original cast, and they clearly enjoyed themselves, musically and dramatically. Mezzo-soprano Elena Zilio was outstanding in the role of Aunt Zita, confident and controlled; while Gwynne Howell made for a distinguished Simone, the head of the grasping clan. They were matched by fine performances from Marie McLaughlin (La Ciesca), Jeremy White (Betto di Signa), Robert Poulton (Marco), Alan Oke (Gherardo) and Janis Kelly (a hand-bag swinging Nella).

From left to right: Jeremy White as Betto di Signa, Gwynne Howell as Simone, Janis Kelly as Nella, Elena Zilio as Zita, Marie McLaughlin as La Ciesca, Robert Poulton as Marco, Thomas Allen as Gianni Schicchi

From left to right: Jeremy White as Betto di Signa, Gwynne Howell as Simone, Janis Kelly as Nella, Elena Zilio as Zita, Marie McLaughlin as La Ciesca, Robert Poulton as Marco, Thomas Allen as Gianni Schicchi

The celebrated aria, ‘O mio babbino caro’, is probably the only number from this dazzling score which is familiar to many in the audience. Here, rather than stopping the show, it was expertly incorporated into the dramatic fabric. Maria Bengtsson charmed and delighted as Lauretta; her powerful, affecting rendition was aptly supported by Pappano, who shaped the phrases sensitively and eloquently. Bengtsson was ably partnered by the American tenor, Stephen Costello who, as the dashing, aspiring young lover, both looked and sounded the part, his ardent tenor ringing out warm and true. In the title role, Thomas Allen gave a typically consummate musical and dramatic performance.

These two stylish, clever stagings offer an evening of light mischief, musical charm and dramatic froth. Delicious — not to be missed.

Claire Seymour

image=http://www.operatoday.com/HEURE-370-DONOSE%20AS%20CONCEPCION-%28C%29PERSSON.png image_description=Ruxandra Donose as Concepcion [Photo by Johan Persson courtesy of the Royal Opera House] product=yes product_title=Maurice Ravel: L’Heure espagnoleGiacomo Puccini: Gianni Schicchi. product_by=Director: Richard Jones. Set Designer: John Macfarlane. Costume Designs: Nicky Gillibrand. Lighting: Mimi Jordan Sherin. Choreography: Lucy Burge. Illusionist: Paul Kieve. Conductor: Antonio Pappano.

L’Heure espagnole — Torquemada: Bonaventura Bottone; Concepcion: Ruxandra Donose; Gonzalve: Yann Beuron; Ramiro: Christopher Maltman; Don Inigo Gomez: Andrew Shore.

Gianni Schicchi: Thomas Allen; Lauretta: Maria Bengtsson; Rinuccio: Stephen Costello; Simone: Gwynne Howell; Zita: Elena Zilio; Betto di Signa: Jeremy White; Marco: Robert Poulton; La Ciesca: Marie McLaughlin; Gherardo: Alan Oke; Nella: Janis Kelly product_id=Above: Ruxandra Donose as Concepcion

All photos by Johan Persson courtesy of the Royal Opera House

Der Rosenkavalier at the MET

If it had been redesigned and restaged by Luc Bondy of this season’s Tosca, the rising curtain would not show us a splendid rococo bedroom with St. Stephen’s Cathedral subtly phallic in the distance but would be placed in an underground dormitory where three strapping stablehands would service the Marschallin whenever Octavian took a breather. No doubt we will live to see such a Rosenkavalier. For the moment, happily, we’ve still got the forty-year-old Nathaniel Merrill production on Robert O’Hearn’s sets, in which pretty much every action seems to take place synchronically with descriptions of or references to that action in Strauss’s score. How very Old Hat! (The hats — and gowns and wigs and uniforms — are probably less old, actually, though still in the proper style.)

Miah Persson as Sophie

Miah Persson as Sophie

Last Monday, the production looked spiffy — how much of it is original

and not rebuilt and repainted, I wonder? — and Edo de Waart led a

sparkling performance of this most graciously autumnal of chestnuts. The comic

business may be familiar, but it went off without a hitch, from the

well-behaved lapdog and the wheezing lawyer in Act I to the dozen sword-waving

hussars in Act II to the raucous children in Act III. Stage direction is

credited to Robin Guarino, and there are some touches I don’t remember:

Did the children always mistake Valzacchi and Faninal for their Papa and have

to be rerouted? (That was funny.) Did the egotistical Singer (Barry Banks, in

full satirical glory) always trample his music in disgust when leaving the

levee? (So was that.) Did Baron Ochs always try to make out with another, more

willing maid of the Marschallin when Mariandel proved elusive? Most interesting

of all, maybe, did the Marschallin always totter about on an imaginary crutch

when daydreaming of her future, aged self? Or has Renée Fleming come up with

that bit in the years since she sang it last? She possesses comic chops she has

scarcely used in her prima donna career — as has been true of

many great stars.

What all this shows is the novelty that can be added, as casts change and work out new business, even in the most traditional stagings of thrice-familiar operas.

Susan Graham as Octavian and Renée Fleming as Marschallin

Susan Graham as Octavian and Renée Fleming as Marschallin

As she has approached the Marschallin’s years (allowing for inflation of the youthful stage from the 1760s to our era), Fleming’s voice has grown thinner, less penetrating on top but fuller, more satisfying in the lower reaches, with less of the famous velvet cream that thrills her fans but annoys those of us who have found her phrasing inexact. These sins were always less noticeable in German roles anyway — Strauss keeps her on her mettle. She was humorous here, as suits a Viennese, and maintained hauteur without the goddess-like dimension Kiri Te Kanawa used to bring, perhaps inappropriately, to the final scene.

Susan Graham makes a more convincing bumptious boy than she does a graceful lady in certain other roles. While Fleming’s voice has lost some luster on top, Graham’s I find thinner, ungraceful, in the lower reaches, more inclined to the blundering quality of “Mariandel,” even when she is singing Octavian’s lines. Her acting is appealing in both the amorous scenes with Fleming and the “flirtatious” punches she gives the Baron whenever he grabs “Mariandel” inappropriately — but the dramatic peak of the night came when Graham and Miah Persson’s Sophie stopped dead, half bowing, eye to eye, infatuated at first glance at the presentation of the rose and seemed almost unable to continue in their aristocratic ritual.

Susan Graham as Octavian, Renée Fleming as Marschallin, Miah Persson as Sophie and Kristin Sigmundsson as Baron Ochs

Susan Graham as Octavian, Renée Fleming as Marschallin, Miah Persson as Sophie and Kristin Sigmundsson as Baron Ochs

Miah Persson has a lively, energetic, easy high soprano, vocally lacking nothing called for by the part, but she lacked for me certain ideal Sophic qualities: there was less girlishness, less poutiness than with most. She was a woman, not a child — but Sophie is specifically a naïve fifteen. Her chatter on being introduced to the Marschallin was too calm for chatter, her breasts seemed awfully prominent and exposed for a girl fresh from a convent, and her grin is too wide; too, she is the tallest Sophie ever to grace this production — she has all the goods for Sophie, but she isn’t Sophie, at least not in this production. Perhaps they play the part more maturely in her native Sweden, a country sadly lacking in aristocratic convents.

Kristin Sigmundsson, tall even beside Susan Graham, made a grabby, sleazy, stingy, you-love-him-because-you-loathe-him Baron Ochs. His grainy voice is not what one would want in a lover in any case, and both his topmost and bottom notes were weak to inaudibility, but he inhabited the role to perfection. Hans-Joachim Ketelsen sang a fine Faninal, less dignified than some — but then, the man is a ridiculous snob, redeemed only because the piece is a comedy with Mozartean aspirations. Wendy White, as Annina, and Jennifer Check, as Sophie’s governess had the loudest voices on stage, though Jeremy Galyon’s policeman came close.

Some of the less well-judged cutenesses that afflicted recent revivals are gone, and the entire presentation is snappier. Either Robin Guarino or Edo de Waart should have most of the credit, but all hands win applause.

John Yohalem

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Fleming_Marschalin.png image_description=Renée Fleming as Marschallin [Photo by Ken Howard courtesy of The Metropolitan Opera] product=yes product_title=Richard Strauss: Der Rosenkavalier product_by=Octavian: Susan Graham; Marschallin: Renée Fleming; Sophie: Miah Persson; Baron Ochs: Kristin Sigmundsson; Italian Singer: Barry Banks; Faninal: Hans-Joachim Ketelsen; Annina: Wendy White. Conducted by Edo de Waart. Metropolitan Opera. Performance of October 19. product_id=Above: Renée Fleming as MarschallinAll photos by Ken Howard courtesy of The Metropolitan Opera

Pascal Dusapin: Faustus, the Last Night

This version of Faust differs from others, since it eschews the traditional narrative which starts with Faust signing a pact with the devil, moves to the sometimes picaresque adventures of the ensorcelled Faust, and ends with the devil claiming his soul. Instead of retelling the story, Dusapin assembled the English-language libretto from various sources to create a text focused on the trials and temptations of Faust during the minutes before his fateful contract with the devil is due. In a sense Dusapin takes his cue from Marlowe’s climactic soliloquy from the end of his Tragical History of Doctor Faustus:

Ah Faustus,

Now hast thou but one bare hour to live,

And then though must be damned perpetually,

Stand still, you ever-moving spheres of heaven,That time may cease ad midnight

never come!....

O lente, lente currite noctis equi!

The stars move still; time runs; the clock will strike;

The devil will come, and Faustus must be damned. . . .

(Act 5, lines 57-61; 66-68)

In creating this work, Faust is not necessarily a character worth saving, with the inanity of his diabolic pact made painfully clear, and Mephistopheles characterized with the dimensionality which makes him more than a minion of Satan, but approaching the persona of Lucifer in challenging the nature of mortal existence. The conversational tone of Faustus, the Last Night may be traced to the kind of opera Strauss created in Capriccio, in the medium foregoes the depiction of physical action to result instead in a shift of thought and concept. (The concept is also used in Henri Pousseu’s Votre Faust (1969), which revolves around a discussion about the prospect of an opera on the subject of Faust.) The conversational aspect of Dusapin’s Faustusalso echoes some elements of early opera, which resulted in various settings of familiar myth. Akin to those early seventeenth-century works, music in Faustus serves as a means to an end, a way for Dusapin to convey the verbal ideas effectively. At times, too, the score functions as a kind of soundtrack in order to allow the work to shift between scenes smoothly and offer cues to mood and tone.

The performers as a whole conveyed the work effectively. The English-language text emerges clearly, and while listeners should not have a problem with the enunciation, subtitles are possible in the original language, as well as French and German. Since the libretto is not published with the DVD, those interested in exploring the text further may use the subtitles as a point of departure (future DVDs like this would benefit from the inclusion of the full text in the digital medium, as a matter of convenience for the user). As Mephistopheles, Urban Malmberg personifies the role. His command of the part is remarkable and serves as a foil for the doomed Faustus, as depicted by Georg Nigl. At times Malmberg and Nigl overlap their lines, as found in the score, and this underscores the blurring of their characters in this work. In Dusapin’s Faustus, Mephistopheles can be as absorbed in thought as Faust. In lieu of a stage devil who simply represents the diabolical forces, Mephistopheles offers some comments which can be as intriguing as the ones Dusapin puts into Faust’s mouth.

This resembles the interchangeability which occurs in modern productions of Don Giovanni in the singers who portray the title character and his servant Leporello sometimes switch their roles between performances. In this sense, Malberg and Nigl work well together in this work to create a good dynamic, and the other principals respond well to it. The angel is one of the more engaging of Dusapin’s characters, and Caroline Stein gave the role the level of definition to counterbalance Mephistopheles. The other two characters, Robert Wörle as Sly (derived from the character in the prologue to Shakespeare’s Taming of the Shrew) and Jaco Huijpen as Togod offer various perspectives on the dilemma in which Faust finds himself. Throughout the performance the conductor Jonathan Stockhammer allows the orchestra to support the singers deftly. His tempos reflect his sensitivity to the text, which emerges clearly in an engaging reading of the score for this new version of the Faust legend.

James L. Zychowicz

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Naive000898.png image_description=Pascal Dusapin: Faustus, the Last Night product=yes product_title=Pascal Dusapin: Faustus, the Last Night product_by=Georg Nigl (Faustus); Urban Malmberg (Mephistopheles); Robert Wörle (Sly); Jaco Huijpen (Togod); Caroline Stein (L’ange | The angel); Orchestre de l’Opéra de Lyon, Jonathan Stockhammer, conductor. product_id=Naïve MO 782177 [DVD] price=$??? product_url=http://astore.amazon.com/operatoday-20/detail/B000H0MH4AOctober 25, 2009

Baldassare Galuppi: Jahel

Had Burney visited Venice and the Incurabili short earlier, on May 24, he might have attended the premiere of Jahel, a Galuppi oratorio recently unearthed at the Zurich Central Library in Switzerland — probably a remake of the score already performed at the Ospedale dei Mendicanti in 1747 and 1748. By 18th-century standards, 23 years was quite a long time-span in the change of musical taste. Perhaps that’s why in 1772 Galuppi reverted to the same subject on a different libretto and with a larger cast of characters under the title Debbora prophetissa, but the core story remained the same, based on chapters 4-5 of Judges in the version provided by the Latin Vulgate Bible.

Actually, despite the triumphs gathered by his operas in London, Saint Petersburg and Vienna, nowhere did Galuppi enjoy more popular acclaim than as a composer of Latin oratorios on Bible subjects for the Ospedali of his native Venice. It is reported that his Tres pueri hebraei in captivitate Babylonis — premiered in 1744 at the Mendicanti — scored some hundred (paying) performances, a feat comparable to those of modern musical theater. Unfortunately, the 1770 version of Jahel is all we are left with in this genre, since two more oratorios surviving in musical sources (Adamo caduto of 1747) and Il sacrificio di Jephtha of 1749) are in Italian.

At the outset of the eighteenth century, the language of oratorios at the Incurabili became exclusively Latin, to remain so under the musical directorship of Porpora, Jommelli, Cocchi, Ciampi, and Baldassare Galuppi. A similar trend affected more or less the remaining three Ospedali. Although the librettists’ choice was for a simplified variety of Latin, aping at the stock imagery from contemporary cantata and opera seria texts, one wonders whether the traditional status of Venice as a target for multinational operagoers could account for such an unexpected association between Latin and bel canto on a scale even larger than in Catholic church-service proper.