January 30, 2010

Bass-baritone eager to sing at home, in English

By Anne Midgette [Washington Post, 31 January 2010]

Eric Owens enjoys singing in English. “I always get so jealous of Italians and native Germans,” says the opera singer. As an American singing opera, “even if you get really fluent, there’s always a certain amount of disconnect, because you didn’t grow up with the language,” Owens says. “When I sing American music, it’s really satisfying to identify and connect so well with the text.”

PURCELL: The Fairy-Queen

Music composed by Henry Purcell. Libretto anonymously adapted from William Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

First Performance: 2 May 1692, Queen’s Theatre, Dorset Garden, London.

| Roles: | |

| Drunken Poet | Bass |

| First Fairy | Soprano |

| Second Fairy | Soprano |

| Night | Soprano |

| Mystery | Soprano |

| Secrecy | Countertenor |

| Sleep | Bass |

| Corydon | Bass |

| Mopsa | Soprano/Countertenor |

| Nymph | Soprano |

| 3 Attendants to Oberon | 1 Soprano, 2 Countertenors |

| Phoebus | Tenor |

| Spring | Soprano |

| Summer | Countertenor |

| Autumn | Tenor |

| Winter | Bass |

| Juno | Soprano |

| Chinese Man | Countertenor |

| Chinese Woman, Daphne | Soprano |

| Hymen | Bass |

Synopsis:

Act 1

The first scene set to music occurs after Titania has left Oberon, following an argument over the ownership of a little Indian boy. Two of her fairies sing of the delights of the countryside (“Come, come, come, come, let us leave the town”). A drunken, stuttering poet enters, singing “Fill up the bowl”. The stuttering has led many to believe the scene is based on the habits of Thomas d’Urfey. However, it may also be poking fun at Elkanah Settle, who stuttered as well and was long thought to be the librettist, due to an error in his 1910 biography.

The fairies mock the drunken poet and drive him away.

Act 2

It begins after Oberon has ordered Puck to anoint the eyes of Demetrius with the love-juice. Titania and her fairies merrily revel (“Come all ye songsters of the sky”), and Night (“See, even Night”), Mystery (“I am come to lock all fast”), Secrecy (“One charming night”) and Sleep (“Hush, no more, be silent all”) lull them asleep and leave them to pleasant dreams.

Act 3

Titania has fallen in love with Bottom (now equipped with his ass’ head), much to Oberon’s gratification. A Nymph sings of the pleasures and torments of love (“If love’s a sweet passion”) and after several dances, Titania and Bottom are entertained by the foolish, loving banter of two haymakers, Corydon and Mopsa.

Act 4

It begins after Titania has been freed from her enchantment, commencing with a brief divertissement to celebrate Oberon’s birthday (“Now the Night”, and the abovementioned “Let the fifes and the clarions”), but for the most part it is a masque of the god Phoebus (“When the cruel winter”) and the Four Seasons (Spring; “Thus, the ever grateful spring”, Summer; ”Here’s the Summer”, Autumn; “See my many coloured fields”, and Winter; ”Now Winter comes slowly”).

Act 5

After Theseus has been told of the lovers’s adventures in the wood, it begins with the goddess Juno singing an epithalamium, “Thrice happy lovers”, followed by a woman who sings the well–known “The Plaint” (“O let me weep”). A Chinese man and woman enter singing several songs about the joys of their world. (“Thus, the gloomy world”, “Thus happy and free” and “Yes, Xansi”). Two other Chinese women summon Hymen, who sings in praise of married bliss, thus uniting the wedding theme of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, with the celebration of William and Mary’s anniversary.

[Synopsis Source: Wikipedia]

Click here for the complete libretto.

Click here for the complete text of A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Prelude to The Fairy Queen — Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment Conducted by William Christie:

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Midsummer_Rackham.gif image_description=A Midsummer-Night's Dream by Arthur Rackham audio=yes first_audio_name=Henry Purcell: The Fairy-Queen first_audio_link=http://www.operatoday.com/Fairy_Queen.m3u product=yes product_title=Henry Purcell: The Fairy-Queen product_by=Pamela Coburn, Soprano; Lynne Dawson, Soprano; Elisabeth von Magnus, Alto; Paul Esswood, Countertenor; Neil Mackei, Tenor; Robert Holl, Bass. Concentus Musicus Wien. Arnold Schoenberg Chor. Nikolaus Harnonocurt. Live performance, 8 July 1992, Stefaniensaal des Grazer Congress im Rahmen der “Styriarte 1992”.In perfect harmony

By Allan Moses R. [The Hindu, 30 January 2010]

French soprano soloist Marion Baglan and pianist François-Marie Juskowiak evoked a thunderous response from a packed audience at The Alliance Française in a concert recently.

January 29, 2010

Lyric Opera of Chicago’s The Merry Widow

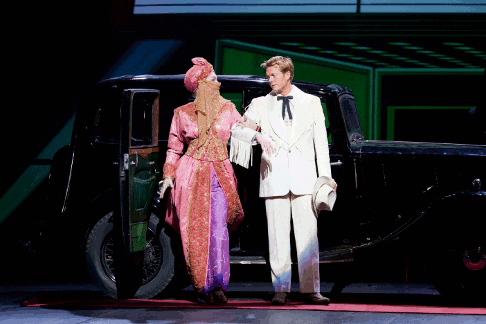

Paris in the opening years of the twentieth century is evoked in shifting venues from the Petrovenian embassy in Act I to the widow’s mansion and to Maxim’s in Acts II and III. The widow Hannah Glawari is sung by Elizabeth Futral in a performance ranging from touching sentimentality to lyrical purity and joyous sparkle in duets and ensembles. Her suitor from the past, Count Danilo Danilovich, as portrayed by Roger Honeywell moves convincingly from the pleasure-seeking rake to the man who still loves Hannah despite circumstances that interrupted their earlier courtship. A secondary romantic involvement is pursued between the married Valencienne and her admirer Camille de Rosillon, sung and acted plaintively in this production by Andriana Chuchman and Stephen Costello respectively. A large supporting cast is drawn into the comedic and wistful resolution of Hannah’s fortunes and amorous interests.

Paul La Rosa, Elizabeth Futral and David Portillo

Paul La Rosa, Elizabeth Futral and David Portillo

After a spirited orchestral introduction led by conductor Emannuel Villaume

the first act of Lehár’s operetta introduces both celebration and

conflict. This scene, as staged in Lyric Opera’s new production,

communicates an appropriate amount of business, replete with arrivals, wooing,

and worries over the homeland. Baron Zeta broaches this latter topic by

accepting congratulations in behalf of the Petrovenian head of state while at

once lamenting the precarious financial issues of the homeland. In his

portrayal of Zeta, Dale Travis assumes a Central European accent and delivers

an effective mix of enthusiasm and anguish. After summarizing the economic

concerns, he insists that the recently widowed Hanna Glawari must remarry a

Petrovenian citizen so that her inheritance might remain in the domestic

treasury. During Zeta’s distracted narration of such details his wife

Valencienne is subjected to the repeated attentions of the nobleman Camille de

Rosillon. Although obviously flattered by these advances, Valencienne expresses

her irritation when Camille writes “I love you” on her fan. In the

duet “Listen please” Valencienne reminds him of her intentions to

remain faithful to her husband Zeta and suggests that he marry another.

Chuchman and Costello fulfill the individual roles of Valencienne and Camille

admirably yet their vocal and dramatic talents seem transformed to a still

higher level when they sing together. In this first duet they epitomize the

conflicts of love and duty as their voices blend to communicate a convincing

emotional fervor.

Stephen Costello and Andriana Chuchman

Stephen Costello and Andriana Chuchman

Once the young couple leaves, the widow Hanna Glawari appears, trying to

deflect the repeated attempts at adulation from men who wish to curry her

favor. In her first aria (“Gentlemen, how kind”) Ms. Futral strikes

a balance between a woman who demonstrates a vocally receptive sense of being

flattered and the realistic widow who suspects any suitor of opportunism. As

Hanna, for the present, leaves and repeated calls for Danilo’s needed

presence are sounded (“Affluent widows double in charm”), the

bachelor enters a near-empty stage. While staggering in apparent inebriation

from the top of a staircase Roger Honeywell portrays Danilo not so much as

dissolute but rather as one avoiding the confrontation of daily responsibility

by losing himself in the swirl of activity at Maxim’s. In his aria

“Oh, Fatherland” Honeywell muses with wistfulness on the duties of

a minor nobleman that he fulfills for his country, but activities of the

evening cause a suspension of the sense of homeland. When Hanna reenters she

finds Danilo, in utter exhaustion, asleep on a divan. Ms Futral attempts to

mask the surprise of Hanna, just as Mr. Honeywell’s Danilo can only

appear confused while he recovers his composure. A renewed attraction between

the principals, interrupted by the realities of an earlier, societal marriage,

is evident for a moment before distance again sets in. Danilo insists that he

will never express love for Hanna, while others vie for a dance with the widow.

When she suggests such a dance with Danilo, he offers it to any other man for

10000 francs. Hanna is incensed and Danilo seems, at first, resolved in his

sullenness. Yet Honeywell shows his character softening, and both agree finally

to the proposed dance. As the act concludes Hanna and Danilo, as portrayed

here, seem temporarily reconciled, if only for the evening, in a dance and song

that bears a glimmer of more for the future.

In Act II of the operetta the action takes place in the garden of the widow’s Parisian home. Hungarian dances are performed first to celebrate the ruler’s natal day: in Lyric Opera’s production both colorful costumes and skillful choreography assure a lively introduction to the celebration. As an extension of these festivities the widow sings the traditional Hungarian song of the vilja. Ms. Futral performed the justly famous song of the wood-sprite, or vilja, with moving emotional force. As she described the feelings of the huntsman who becomes enamored of the sprite in the forest, Ms. Futral’s character itself seemed to bloom, so that buried emotions could again be kindled. A further encounter with Danilo, who arrives to participate in the widow’s reception, contributes to renewed confusion and bruised emotions, with both characters stomping away in opposite directions. The scene is then left to the naïve pair Valencienne and Camille, who both avail themselves of the solitude to discuss openly the state of their love. Despite the protestations of Valencienne, Camille serenades her with the aria “Just as the rosebud blossoms in the light of May.” Mr. Costello flourished here as an ardent lover in the solo aria in which his vocal modulations and use of legato were especially well received. The two withdraw into the garden’s pavilion in time for Valencienne’s husband Zeta to return and peer curiously into the enclosure. Although he at first believes that he sees his wife with Camille, Hanna changes places with Valencienne in order to save her reputation. The widow and Camille emerge from the pavilion declaring their intention to marry, an announcement which confuses Zeta and irritates even further Danilo. Mr. Honeywell gave convincing expression to his pique in the aria “Fall in love often,” as he rushed off at the close of the act to console himself in diversion at Maxim’s.

Roger Honeywell and Elizabeth Futral

Roger Honeywell and Elizabeth Futral

It is indeed here at Maxim’s that the numerous conflicts and emotional tensions are ultimately settled during Act III of the operetta. After the mood is set by an orchestral introduction including strains from the “Merry Widow Waltz,” we see the various girls of the club along with Valencienne dancing to entertain Danilo. Further communication from the homeland prompts the widow to admit that she never intended marriage to Camille and that her motives consisted in the protection of another woman’s honor. At this Danilo admits his love for Hanna, and they sing the duet “Strings are sighing.” Futral and Honeywell express their bond, leading eventually to the consent of marriage, in touching unison as they conclude aptly on the lines “We’ve gone soaring to the heights” and “It’s you I love alone!” Only the breach between Valencienne and Zeta must be repaired. When the jealous husband discovers the fan on which Camille had written of his love, Valencienne convinces Zeta to read the declaration on the reverse: “To my loving husband from his adoring wife.” All is now well in the emotional world of The Merry Widow, as depicted in Lyric Opera of Chicago’s delightfully musical production.

Salvatore Calomino

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Futral_MW_Chicago.png image_description=Elizabeth Futral as Hanna Glawari [Photo by Dan Rest courtesy of the Lyric Opera of Chicago] product=yes product_title=Franz Lehár: The Merry Widow product_by=Hanna Glawari: Elizabeth Futral; Danilo: Roger Honeywell; Valencienne: Andriana Chuchman; Camille: Stephen Costello; Baron Zeta: Dale Travis; Njegus: Jeff Dumas; Raoul St. Brioche: David Portillo; Viscount Cascada: Paul La Rosa; Pritchitch: Larry Adams; Kromov: James Rank; Bogdanovich: Bernie Yvon; Sylviane: Mary Ernster; Praskovia: Ann McMann; Olga: Susan Moniz. Conductor: Emmanuel Villaume. Director: Gary Griffin. Set Designer: Daniel Ostling. Costume Designer: Mara Blumenfeld. Lighting Designer: Christine Binder. Projection Designer: John Boesche. Chorus Master: Donald Nally. Choreographer: Daniel Pelzig. Ballet Mistress: August Tye. Wigmaster and Makeup Designer: Richard Jarvie. product_id=Above: Elizabeth Futral as Hanna GlawariAll photos by Dan Rest courtesy of the Lyric Opera of Chicago

January 28, 2010

Simon Boccanegra, New York

Simon Boccanegra excited his particular ire: he would waste three or four paragraphs trying to figure out the plot and then toss out the name of a singer or two. How many people do go to a Verdi opera for the sake of the plot? I hoped he was the only one — but the other night, on the bus down Broadway after this latest Met Simon, I heard a couple of opera-goers complaining that they found Simon more incomprehensible than Trovatore (I find Trovatore crystal clear, by the way), and an old friend said, “How come Fiesco, after twenty-five years in disguise, just happens to become the guardian of an orphan who just happens to be his lost granddaughter?” This is, of course, a stumbling block, what the French call, translating another Verdi opera, La force de la coïncidence. You should do what Verdi did with such absurdities: Ignore them and focus on the music. The plot is not what the opera is about — not this opera.

What Simon is about — besides the father-daughter theme (here also grandfather-granddaughter) always explosive in the operas of the childless Verdi — is color. The prologue, for instance, set in an alleyway in fourteenth-century Genoa, includes confrontations among four characters, not one of them of a higher voice than baritone. Even the offstage women’s prayers for the dead are offset by a basso Miserere. All the murky political and personal doings are shrouded in shadow, and this shadow only dissipates in Act I against the shimmering dawn-over-the-sea music of Amelia’s aria, yet even her happiness at the beauty of the scene and at finding true love is intruded upon by minor-key forebodings. The whole opera is prevailingly dark, with only the shimmer of the sea, the warmth of the glorious father-daughter duet and the occasional beacon of the one soprano voice in the great crowd scenes that end Acts I and III.

I call this Verdi’s “light-in-the-darkness” period, a series of experiments he made in tonal color by setting a single soprano to shine out over massed crowds of dark sound. Thus we have Leonora’s “Vergine degli angeli” in Forza, Oscar’s high melody in “E scherzo od e follia” in Ballo in Maschera, the Celestial Voice in Don Carlos, the priestess in Aida. The effect is to make the drama personal, to remind us that amidst the mobs carrying us along in life’s big events, the individual soul is suffering individual anguish. Leonora de Vargas isn’t just joining the monks in prayer — she has her own guilt to expiate, her own questioning of God’s purpose; Oscar is not merely apprehensive at the witch’s prophecy, he is a believer in her powers, which suddenly seem to threaten his beloved sovereign; the priestess does not merely hope for the triumph of the choral manhood of Egypt, she seems to be making a direct appeal to “immenso Ftha” for divine favor.

Adrianne Pieczonka as Amelia Grimaldi

Adrianne Pieczonka as Amelia Grimaldi

In Simon Boccanegra, God is not the problem; politics are — to the point that Amelia’s personal problems could be overwhelmed in mob violence, here vocalized. But all politics are local, and Verdi presents the individual point of view by having her soprano trill through the dark concertato that ends Act I, her descending arpeggio of mourning riding free beside her father’s deathbed in Act III. Verdi has evoked the darkness of grim scheming and civil conflict, but Amelia’s voice reminds us of individual experience and personal loss.

My Amelias go back to Gabriela Tucci and have included Maliponte, Arroyo, Te Kanawa, Mattila, Guryakova and Gheorghiu — all superb except the last, whose voice seemed small for Verdi in a room the size of the Met. On this occasion, Amelia was sung by Adrianne Pieczonka, a handsome woman whose voice is cool, lovely, and sizable without audible effort, but her “Com’e in quest’ora bruna” was uneven, with a swoopiness whenever she leaped above the staff that was also present for the rest of Act I. In her duet with Domingo (is there a lovelier father-daughter duet in all Verdi?), she was better when leaps were not required of her, but the great trill in the concertato was mud. She warmed up in Act II, and the arpeggios that must gleam at Simon’s deathbed did so. It was not clear whether the Canadian soprano was having a difficult night or was simply miscast. The Met needs a Verdi soprano with a voice this big and beautiful, but she should be in better control of her instrument.

Plácido Domingo’s decision to take on the baritone doge’s role (not his first such exploration at the Met — he has sung Gluck’s Oreste here) was surely the reason the Met was packed, and the crowd was so unfamiliar with the opera and with the baritone color in which he sang that they failed to greet his initial entrance with intrusive applause — bravos all round for that! The applause (and flowers) at evening’s end made up for that to be sure. His performance was more than satisfactory — from a tenor-out-of-water at nearly seventy, it was a far more finished a vocal interpretation than, say, José Cura’s Stiffelio. Domingo has always been a baritonal tenor — to the frustration of those tenor-lovers who like the near-desperation certain voices make in attaining high notes. Domingo recorded bits of Rossini’s Figaro and Verdi’s Posa long ago, but Simon is one of Verdi’s signature baritone parts. There was a sense that the lower depths, the baritonal resonance, the depth and echo, were not well served, that he does not resonate there — but he was on pitch and in character, clearly enjoying his interactions with old friends like James Morris and James Levine.

Plácido Domingo as Simon Boccanegra, Adrianne Pieczonka as Amelia Grimaldi, Marcello Giordani as Gabriele Adorno and James Morris as Fiesco

Plácido Domingo as Simon Boccanegra, Adrianne Pieczonka as Amelia Grimaldi, Marcello Giordani as Gabriele Adorno and James Morris as Fiesco

Marcello Giordani sang like a god in Act I and grew a little sloppy thereafter, though without the strain and pitch problems that have sometimes dogged him in Donizetti. Verdi is the right place for him.

James Morris no longer sings Wotan or Hans Sachs, but his Fiesco reminds us that in his early decades he was known for his Mozart and bel canto. No longer having great caverns of voice to draw upon, he husbanded his resources well and sang on the lighter side of this dark role, without wobble and without disgrace. Patrick Carfizzi made an appropriately histrionic Paolo, the slimy fixer of Genoa, catching the character’s inner torments and rages with a serene Verdi line. Paolo is often an apprentice Simon, as Ford is an apprentice Falstaff, and Carfizzi should be interesting when he takes up the title role.

In James Levine’s capable hands, all the parts of this subtle score interacted smoothly whether the singer was staring only at him — as Domingo usually did — or not. The music of the great duet seemed to breathe with the surf rolling into Genoa, and Verdi’s intricate games with strings and winds created a sense of symphonic mood, a pervading unease highlighted by the thundering brasses he would use again and again in the operas that followed.

Giancarlo del Monaco’s production in Michael Scott’s colorful sets does not clarify the complicated plot, beginning as it does in fourteenth-century Genoa (as Verdi desired) and then apparently lurching to seventeenth-century Venice in the Council Chamber scene for no reason except that Tintoretto on the ceiling looks pretty and nobody knows what the Genovese council chamber did look like. Peter McClintock has elided some of Del Monaco’s more hamhanded bits of direction — crowds move naturalistically, a happy change, and Fiesco no longer draws a sword to rush at Simon three times in the course of the opera; only once. Still, as he never does lay a paw on him, these madcap outbursts tend to make Fiesco look ineffectual at best. Verdi intended Fiesco to possess a dignity evidently beyond Del Monaco’s narrow imagination.

John Yohalem

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Domingo_Boccanegra.png image_description=Plácido Domingo as Simon Boccanegra [Photo by Marty Sohl courtesy of The Metropolitan Opera] product=yes product-title=Giuseppe Verdi: Simon Boccanegra product_by=Simon Boccanegra: Plácido Domingo; Amelia Grimaldi: Adrianne Pieczonka; Gabriele Adorno: Marcello Giordani; Fiesco: James Morris; Paolo: Patrick Carfizzi; Pietro: Richard Bernstein. Metropolitan Opera chorus and orchestra, conducted by James Levine. Performance of January 25. product_id=Above: Plácido Domingo as Simon BoccanegraAll photos by Marty Sohl courtesy of The Metropolitan Opera

New Music Director for Opera Orchestra

By Dave Itzkoff [NY Times, 28 January 2010]

Eve Queler, the founder and longtime music director of the Opera Orchestra of New York, who has seen the institution through recent financial struggles, is preparing to step down. The orchestra said in a news release that it had appointed Alberto Veronesi, the Italian conductor, as music director starting with its 2011-12 season.

January 25, 2010

Le Poème Harmonique

By Allan Kozinn [NY Times, 26 January 2010]

Emilio de’ Cavalieri, though hardly known today, was a friendly competitor of the Florentine Camerata, the group of musicians and theorists whose ideas about text setting and drama led to the creation of opera around 1600. The Camerata’s style came to represent early Baroque vocal music as we know it. But Cavalieri’s music offers a fascinating glimpse of an alternative approach, and the performance of his “Lamentations of Jeremiah” by the French early-music ensemble Le Poème Harmonique at the Church of St. Mary the Virgin near Times Square on Saturday evening captured his distinct, sometimes exotic accent.

War and Peace, Theatre Royal, Glasgow

By Andrew Clark [Financial Times, 25 January 2010]

It is a popular misconception that masterpieces arrive in fixed form, like a gift from heaven. Some of the most successful operas - Carmen, Don Carlos, Boris Godunov , to name but three - have extremely messy histories, and until recently no one bothered if the edition was bowdlerised.

Florida Grand Opera's Eglise Gutiérrez lifts `Lucia di Lammermoor ' to modern heights

By David Fleshler [Miami Herald, 25 January 2010]

As traditionally performed, Donizetti’s opera Lucia di Lammermoor is 2 ½ hours of Scottish castles, mist-shrouded lakes, swordsmanship and tragedy.

London’s Rambunctious Rake

First and foremost, the Royal Opera House’s Rake boasts an A-list cast that is as fine as can currently be assembled. Of especial interest to me was young bass Kyle Ketelsen’s role debut as Nick Shadow. He definitely did not disappoint. Mr. Ketelsen always offers a consistent, rich, and suave tonal delivery and he is possessed of one of the most secure techniques of any voice heard before the public today.

His is a sizable instrument which can easily ring out in the house one minute, and scale back to a hushed, intense sotto voce the next. He bought his usual intelligence and superb musicianship to bear in what has to be considered a major role assumption in his growing repertoire (and reputation). As wonderful as is his vocalizing, Kyle also scores big — make that waaaaaay big — as an actor. In fact, I would be hard pressed to think of any male singer active that is his equal for stage presence, character delineation, vocal color, uninhibited movement, and dramatic understanding. The card scene could have served as Masters Class in theatrical nuance.

Repeated performances and even more experience will only deepen his already commendable interpretation. You heard it from me: Kyle Ketelsen will be the Nick Shadow of choice for future productions. I am not alone, the entire audience roared its approval with a vociferous ovation.

Happily, he was in great company. Toby Spence as Tom Rakewell served up splendid, secure singing all evening, and he managed to touch me deeply in his final scene as no one has before. My previous outing with the staged opera was limited to two disparate but troublesome productions in Aix and Salzburg respectively, but both starring the late Jerry Hadley in one of his best roles.

Although Jerry had more squillo in his voice, the concepts sadly kept him on the surface of the role. Mr. Spence was able to delve deeply into the character’s psyche, and while he appears and acts suitably boyish, his real-time maturity has been deployed effectively in defining Tom’s life journey and descent into madness.

He is a highly accomplished lyric tenor to be sure, but like many such well-schooled light voices, the artist can be counted upon to deliver more in the area of consistency of pleasing tone, than can be easily offered in terms of varied dramatic utterance. It is to his credit that he used his considerable acting skill to create a plausible illusion of varied tonal color.

Toby Spence as Tom Rakewell and Rosemary Joshua as Anne Trulove

Toby Spence as Tom Rakewell and Rosemary Joshua as Anne Trulove

Another brilliant lyric voice and vibrant stage presence was on hand in the person of Rosemary Joshua’s Anne. This wonderful artist goes from strength to strength and she, too, has an awesome arsenal of technical skills at her command. Just listen to her soaring fearlessly through the most angular phrases and meandering melismas, and then turn around to melt our hearts with utterly focused limpid singing of the first order. Kate Royal had been advertised for the part, but while Ms. Joshua offers a slightly more mature take on the role, she is slim, lovely, and still has the Wow Factor for me, as when I first heard her Cleopatra in Miami and said “Wow, who is this fabulous soprano?”

Patricia Bardon, a veteran of the 2008 mounting of this production, returned as Baba the Turk and successfully managed her rich bottom range and ringing top to deliver a fully committed traversal of one of opera’s most unique characters. She looked smashing, too, pulling off the difficult task of being bearded but yet seeming alluringly sexy. Stalwart comprimario Graham Clark treated us to a vocally secure and theatrically vibrant turn as the auctioneer Sellem, and company principal Jeremy White was solid of voice and stature as Trulove. Frances McCafferty seemed game to do anything (and did) as a randy Mother Goose, although there were a few frayed notes at the extremes of the range.

The orchestra had a remarkably fine night, not only playing the rhythmically challenging score cleanly, but also investing Stravinsky’s masterpiece with all the vibrant panache and passion it needs to make its mark. This can be attributed to the controlled baton of Ingo Metzmacher. I have encountered the maestro’s work on several occasions now. He is never less than inspired, and his musical stewardship is never less than remarkable. It is pleasure to watch his star on the rise.

Kyle Ketelsen as Nick Shadow

Kyle Ketelsen as Nick Shadow

Stage director Rober Lepage is always preceded by his large reputation, and for once it is a reputation founded on thoughtful experimentation informed by a respect for the original work. Mr. Lepage’s interpretation of this challenging piece is never less than hugely entertaining and ultimately it is enormously affecting. He has managed to find the honesty in Auden’s dark humor, and delivered some well-calculated laughs all the while retaining the underlying serious narrative. He was ably abetted in this fanciful pursuit by the witty set design of Carl Fillion; the colorful, characterful costumes by François Barbeau; and the evocative lighting devised by Boris Firquet. (It should be noted that Sybille Wilson has directed the revival, presumably with fidelity to the original staging.)

The production team has loosely devised their vision around a concept of Hollywood in its (now-) glorified heyday, with nods to such iconic films as Sunset Boulevard, The Snake Pit, Destry Rides Again, A Star is Born, among others. Nick Shadow is presented as an old school film director, a veritable Cecil B. De-vil, often riding herd and riding high over the proceedings from a camera crane and therefrom controlling the fates of his players.

This decidedly allowed for many images of great resonance, and some wholly engaging set changes which we came to anticipate with relish. I will never forget the slow inflation of Tom’s blow-up Hollywood star dressing trailer, or the disappearance of the lasciviously poised Goose and Tom as they sunk through the center of the red draped bed to the depths of the trap door, nor Anne’s goofy convertible car ride with scarf billowing in the breeze.

However, it has to also be said…it didn’t quite work as a totally integrated piece of theatre. At the end of the day, had I not read the program notes I might not have grasped this overall conceit until we were well into the piece. Unlike the recent Fanciulla in Amsterdam that established its intent early on to tap into Old Hollywood images, this Rake apparently began on a flat plain with an oil derrick in …where? Texas? Oklahoma? I was willing to go with that, but it soon seemed a red herring of sorts. When we finally start to get it, we wasted some time and attention playing catch-up in retrospect.

Patricia Bardon as Baba the Turk and Toby Spence as Tom Rakewell

Patricia Bardon as Baba the Turk and Toby Spence as Tom Rakewell

Nevertheless, it cannot be denied that The Rake’s Progress was a highly diverting, conscientiously considered, and wholly professional evening at the opera. By assembling a world class cast and pairing them with its usual awesome musical and theatrical assets, the Royal Opera House has once again reminded me that it is Europe’s premiere company.

James Sohre

image=http://www.operatoday.com/ROH01341.png imagedescription=Toby Spence as Tom Rakewell [Photo by Johan Persson courtesy of the Royal Opera House]

product=yes

producttitle=Igor Stravinsky: The Rake’s Progress

productby=Trulove: Jeremy White; Anne Trulove: Rosemary Joshua; Tom Rakewell: Toby Spence; Nick Shadow: Kyle Ketelsen; Mother Goose: Frances McCafferty; Baba the Turk: Patricia Bardon; Sellem: Graham Clark. Royal Opera. Conductor:

Ingo Metzmacher. Director: Robert Lepage; Revival Director: Sybille Wilson; Set Designer: Carl Fillion; Costume designs: Francois Barbeau; Lighting Designer: Etienne Boucher; Video: Boris Firquet; Choreography: Michael Keegan Dolan.

product_id=Above: Toby Spence as Tom Rakewell

All photos by Johan Persson courtesy of the Royal Opera House

Stirring Storytelling and Amorous Rapture

By Steve Smith [NY Times, 25 January 2010]

Ask any serious vocal enthusiast to provide a list of the finest singers currently working, and the chances are good that Bernarda Fink, an Argentine mezzo-soprano, will figure in. Here in New York, where Ms. Fink has appeared infrequently, her renown stems primarily from her performances on CD, including opera recordings conducted by René Jacobs and highly desirable recital discs on the Harmonia Mundi label.

Kerry Andrew — An Interview

TM: Where were you born and raised?

KA: I was born and raised in High Wycombe, which is a nondescript town in Buckinghamshire, outside London.

TM: What sort of music were you exposed to in your family as a child?

KA: My parents aren’t musicians, and don’t play instruments, but my dad was always interested in singing. Once I was about ten, I joined the church choir with him. I lived in Canada, when I was very small, for three years, and my parents got into a lot of country music. I listened to a lot of classic country, like Johnny Cash and Willie Nelson.

TM: When did you go to Canada?

KA: When I was very small, age three to six. Not old enough to take much in, I don’t think.

TM: Where did you live?

KA: We lived in Toronto.

TM: Was it a shock to move there from the London area?

KA: It was more of a small culture shock coming back. Not for very long, because I was still tiny. My Canadian accent was dispelled pretty quickly. I have never been back, actually — I would love to go back to Canada. I have always meant to, and haven’t quite made it.

TM: So your father sang in the church choir.

KA: I joined quite soon after him. I sang for ten years.

TM: Was this Church of England?

KA: Catholic. And Catholic choirs in the UK are pretty bad! You get much better choirs at the Church of England than you generally do in Catholic churches. Nobody is paid to sing in a Catholic choir except for in very posh Catholic churches in London, so it’s often rather amateur. But I learnt to sing in parts there, which was hugely valuable.

TM: The same is true in the United States, with the best music at the Episcopal Church. You must also have explored other musical areas as a child.

KA: Nothing out of the ordinary. I went to school, and like many school kids, at least then, I learned two instruments - first the flute, then the piano. I got a scholarship at a weekend music center, which I went to from the age of 10 to 18 — so every Friday night and Saturday morning I was doing extra music, mostly classical.

This was in High Wycombe, at a music center that is still going. You got to do choir, theory, musicianship, a couple of instruments, and wind orchestra or orchestra, depending on what you were playing. It was really good, really good. Without all that extra weekend activity I am sure that I would not be a musician now.

TM: For those of us in the USA the English educational system is a mystery. What sort of schools did you go to?

KA: I went to a very ordinary state primary and middle school until the age of 12, and in Buckinghamshire, you did the 12+. If you passed you went to a grammar school, so I went to a girl’s grammar school for the next six years, up to eighteen. It works in different ways all over the country, so you can have non-fee-paying grammar schools, but you still pass an exam to get there. There are private schools, independent schools, and state schools.

TM: To have a public school that is just boys or just girls in the USA is very unusual. What was the music like there?

KA: It was quite traditional, but very good. I was the only one, when I was sixteen to eighteen, who was picked to do two music A-levels — I did theoretical music and practical music. The exams were quite intense, actually, but I was given one-to-one tuition to do that.

TM: You were singing, and playing flute, and piano. Do you still play flute and piano?

KA: I play quite a lot of piano. I am a bit of a jobbing piano player — I couldn’t give a concert, but I play piano in one of my bands, and for all of my teaching. I should pick up my flute. One of my New Year’s resolutions last year was to pick up my flute again, and I played it once, on about January the fifth! I am just too busy.

TM: Did you listen to pop, or rock, or jazz? World music?

KA: Jazz: not until a lot later. I listened mostly just to pop music, influenced by what was in the charts. When I was ten I was into Kylie Minogue and Jason Donovan! By the time that I was sixteen, it was lots of British indie bands and a bit of hip-hop. I was a slow developer — you get a lot of prodigious talents who are listening to Berio at age seven, or John Coltrane at age nine… I was just not like that!

TM: When you left grammar, you went on to university.

KA: At York University. It has a fabulous music department — I will praise it to the hilt, because it’s brilliant, and I had the time of my life there. I did a degree in music, and stayed on and did a Masters in Composition. Then I did a Ph.D in Composition, first part-time, while I was living in London, and then I went up and finished it off full-time. All in all, I was at York for about nine years. So I must really like the place!

TM: We Americans have no sense of scale for England. How far was York from London by train?

KA: Just under two hours.

TM: It seems like it must be impossibly far north, if you think of Michael Palin and his Yorkshire accent.

KA: It’s a great city. For me moving from a slightly dull town to a bijou city was a really good move. There was just enough culture there for me to ease myself in — it would have been a shock if I had moved to London straightaway.

I think the department is starting to change now, actually. For a long time you could choose all the modules that you wanted to do — you didn’t have to do a rigorous training in theory and orchestration and music history — you went straight in and did loads of practical, fun projects. You could choose a project a term, from Popular Music to studying Debussy, from Electroacoustic Composition to Community Music — you could mix and match, and tailor your degree to suit you.

TM: Which did you choose?

KA: I did Popular Music early on, and did a hip-hop project. I have always really loved hip-hop. I revisited it for my MA, and did a seminar on the history of hip-hop, or the way it was then. I did Debussy, and Music Education which was very valuable, because I do so much music education now. I did a lot of composition, and I ended up doing a lot of music theater — experimental music theater, not musical theater — as director, producer, or musical director, and sometimes a performer. And I ended up singing. I have never really had any singing lessons, although now a lot of my living is singing. I was exposed to so much there - being in choirs, and singing a lot of new music — that it got me to where I am now.

TM: At what point did you decide that you wanted to be doing composition?

KA: At sixteen. I wanted to go to a college, like the Royal College of Music, and was encouraged not to by my music teachers, who thought that a university department with a real spread of musical activities would be much better for me than just having a composition degree. I wouldn’t have ended up singing had I done composition at the Royal College, had I even been given the place.

There are great composers teaching at York: Roger Marsh, Bill Brooks, Nicola LeFanu, who has just retired recently. Roger Marsh was my teacher for quite a few years, and he was a big influence.

TM: Could you say a little more about those two?

KA: Nicola LeFanu was the head of the department when I started. She writes very beautiful, often quite detailed contemporary classical work, which has included several operas. Roger Marsh has written experimental music theater works, music using interesting texts, and music drawing on Japanese music, which is something that I have gotten into as well.

TM: Were there particular models of composition that he was imparting?

KA: No, it was quite open. You studied a lot of twentieth-century music, and eventually you wrote your own pieces. What was great about York was that there was such a strong culture of not just writing new music, but playing and performing it, so students were willing and ready to try out your work. It was a fantastic environment for trying out new ideas.

TM: What choirs did you sing in at York?

KA: They had a chamber choir and a larger university choir. The chamber choir split so that there was an extra small chamber choir just for performing new music, and I was quite involved in that one. There is now a really good ensemble called The 24 which solely performs new music, and that is run by the great tenor John Potter, who is a great influence on the group that I am in, juice. He’s been instrumental in developing the new music side of the vocal department at York. He’s recorded John Dowland songs with the likes of double bass player Barry Guy and saxophonist John Surman, he works extensively with Gavin Bryars, and has an ensemble called Red Byrd — he’s fabulous.

TM: Yes indeed. Perhaps you could talk about your choral music. So much sacred music is in such poor taste, and your works are fresh and different, but still drawing on the English choral tradition. What would you say are the sources for your inspiration?

KA: Although I sang in a church choir for many years, it was a Catholic choir, and we weren’t singing wonderful pieces by Howells [said with a smile], or Stanford or Parry, or anything like that. I did sing quite a lot of good sacred music once I was at university.

The choral music I write comes from a mixture of the little church music that I have known, but mostly from listening to much more experimental vocal ensemble music or choral music by people like — I know you won’t think it from listening to dusksongs — Berio and Xenakis and lots of Meredith Monk. At university I didn’t write traditional choral music — I wrote quite experimental works. The reason that I have ended up writing a lot of decently successful choral music is because I entered a piece in the Temple Church Choir Composition Competition, and won. From that Oxford University Press, who are my main publishers, asked me to write a piece, and it’s just developed from there. The commission from the Ebor Singers for dusksongs came from my having established myself with the OUP publications, and the fact that they know me from York, since it is a York-based ensemble.

I am interested in vocal music generally, so although I have written a lot of sacred choral music, it’s because I have been asked to. Even though I grew up in the Catholic Church, I am a total atheist now, quite emphatically so.

I am really interested in words as well. I am interested in vocal music because I love writing, and have always written poetry, some of which has been published in small presses. I have written lots of lyrics. What I always enjoy doing, and this is also true for the sacred music, is just responding to the words. That’s the most important thing. I try to find a way to make words as interesting and illuminating as possible.

TM: To go back a little, what piece was it that won the competition?

KA: A piece called maranatha. It was for the first of the Temple Church Choir Composition Competitions in 2002. They gave a number of texts that you might want to set for a five-minute choral work. The first text was just one word — maranatha. It is Aramaic, and means “Lord, come!” or “The Lord has come”. At the time, at university, I had been getting into setting really small bits of text, splitting them up, using just tiny bits of words, and exploring their sonic possibilities. I decided to choose that word, maranatha, because it was the shortest, along with the fact that it has these two meanings. I explored the sounds of the mmm — aaa — rrrr aaa—naa-tha. The piece won, and Faber Music decided to publish it. It was a good start.

TM: What came next?

KA: O lux beata Trinitas, which Oxford University Press asked me to do, to be included in a book of anthems, for quite competent choirs; from the suggested texts I chose a lovely Latin one. I like to combine languages, so there was Latin and English, with the two going alongside each other. Paul Gameson got the Ebors to perform it, and they liked it so much that they thought they would create a commission using this as a starting point. And so the Compline Mass, dusksongs, has O lux beata Trinitas as its final movement.

TM: You have various other venues as a performer. Could you talk about juice?

KA: juice (www.juicevocalensemble.net) is a trio that I co-founded with Sarah Dacy and Anna Snow. We all went to York, so we have all come from that brilliant vocal department, and been influenced by the likes of John Potter, and all the music we were exposed to — Berio, John Cage, Meredith Monk. We had sung together a little bit at university and found that we had a rapport, and when we all moved to London in 2003 we officially formed the group. We are an experimental vocal trio coming from a contemporary classical tradition, which is still our core, but we are also really interested in singing elements of folk music, world music, jazz and pop, as long as there is something a little bit twisted or experimental about it. We try to put quite eclectic programs together. We’ll do music with electronics, or electronics and visuals, a little bit of music theater, sometimes collaborations…

TM: Is there a CD out yet, or is that on the way?

KA: This year hopefully! We’re part of a loose alternative classical scene in London, with other groups like ours mixing contemporary classical with elements of pop or electronica. Other groups are the Elysian Quartet, Sarah Nicolls, a pianist who does a lot of stuff with electronics, and Gabriel Prokofiev, who is a composer and DJ, and runs the ‘nonclassical’ label, which we should be on in 2010. We hope to start recording soon, and it will be out at some point later in the year.

TM: Music for just voices?

KA: It’s still undecided, actually. Gabriel’s initial albums on nonclassical were his own string quartets, for the Elysian Quartet, where you would have a four-movement quartet, which he would get DJs and producers to remix, so you have a part-acoustic, part-remixed album. That’s generally the format of the nonclassical releases so far. Gabriel and juice are trying to decide if it will be just a cappella, or juice and electronics, or a cappella pieces and remixes.

TM: You mentioned the various influences on juice. How do these filter into your life? Do you seek them out?

KA: It’s a real mixture. It’s from recommendations, it’s me finding artists on MySpace, searching around online….All of juice’s ears prick up when we hear a group or a vocalist doing something new and exciting with their voices. We’re big fans of Zap Mama, who are quite an influence on us. Do you know them?

TM: They were big in the United States.

KA: A lot bigger than they were in the UK.

TM: They were huge — everybody knew who they were.

KA: Their first album was a big influence.

TM: Tell me about your alt-folk thing.

KA: I have been working on my own solo stuff for about a year, under the name You Are Wolf (www.myspace.com/youarewolf). I wanted to explore folk music, because it was something I had listened to for the last fifteen years — English folk music in particular. I have been arranging English folk songs using a loop station, which enables me to perform basically solo, feeding my voice into the loop station, and building up vocal layers around the songs.

TM: You mentioned enjoying twisting music with juice. How do you twist around the folk music?

KA: The first song on my soon-to-be-self-released EP is called “All things are quite silent”, which I picked up from an English folksong book, just the melody and the words. I have never heard a recording, so I didn’t come to it with any preconceptions. I learnt the tune, and developed a layered vocal version, where I take a couple of bits of the beginning of the folksong, and create loops out of those that go on underneath. I explore treating my voice, making it sound like the sea, bleeps, whistles, and cracks, and I tried to turn it into a very dark song. It’s about a girl losing her man to the sea — he’s gone off to be a sailor. The last verse is faintly optimistic, where she hopes he will come back soon. I sing those words, but underneath I produce all these cracking, creaking, nasty-sounding effects from my voice which suggest that …

TM: …he’s not coming back.

KA: There’s a lashing sea and wind…I guess that’s a good example of twisting it up.

TM: How do you integrate Berio and Xenakis? I know the Cries of London by Berio, but I wouldn’t have thought of Xenakis as having much connection with the vocal world. It seems like it takes someone with extensive experience with the voice to write effective choral music.

KA: I agree — that is usually the case. I say Xenakis because I studied his piece Nuits which is a really good choral work with lots of microtonal writing, all in these lovely little blocks. It was an influence on me because I have been interested in having lots of vocal lines doing very similar things all at once.

I teach a lot of projects on composing for voice with juice, and we always say “sing your music”. Even if you are not a singer, don’t sing in a choir or in public, it’s all about getting it in your voice. Sometimes you get composers who write difficult, angular things for the voice that don’t feel very natural. That’s not to say that you can’t write difficult, angular material for the voice, but some work better than others. I always recommend singing your parts, just to see if it generally feels natural, works with the words, and works within the range of the voice.

It’s very useful to be in juice, and have so much experience about how a vocal ensemble works. Knowing how voices relate to each other when you haven’t got any backing, any piano or organ or anything else, knowing about voice-leading and tuning. I am lucky that a lot of that comes naturally to me because I have done so much of it. That said, I can’t write a string quartet to save my life! It’s what you know.

TM: The composers who take this route to composition are few. In 1500, in England, if you were a composer, you were a singer, but not anymore.

Frequently there seems to be a connection between the scene for early music and the contemporary music scene, with musicians who may not do much in between doing both sixteenth and twenty-first century music, for example. Is there a connection for you between the early music scene and what you do?

KA: Not really!

TM: Though you mentioned John Potter.

KA: John Potter is someone who makes that connection, both as a soloist with his John Dowland work for example, and in his previous work in the Hilliard Ensemble. Trio Medieval are another ensemble who sing mostly early music, but do some contemporary music as well. If you sing early music you have a straighter voice which, perhaps, suits a lot of contemporary writing. It depends.

I quite like listening to early music, and I personally love a straight vocal sound, both in choral music and in solo or small ensemble singing. But juice doesn’t sing any early music — we are all about the now!

TM: Are there other areas you are moving into or would like to explore further?

KA: I am in two other bands, actually. I sing with a group called Metamorphic, who are a jazz sextet, doing original jazz. I also co-founded DOLLYman (you can hear us at myspace.com/dollyman). Until recently we were a four-piece group, all from York at some point, with me singing and playing some piano, melodica and glockenspiel. We have James Lindsay, a cellist who also sings and plays keys, Matt Dibble who is a fantastic clarinet and sax player, and Lucy Mulgan, who is a bass player. We have spent a couple of years having a lot of fun. It’s not professional, it’s just fun. We all write material for the band which is sort of jazz……..ish. There’s a bit of jazz, a bit of experimental classical music as well, a bit of pop. And now we’ve got a drummer, Pat Moore, so we feel more like a proper band - ha!

TM: Is there a CD in the offing?

KA: We are talking about recording this month or next month, but I can’t make any promises!

TM: What sort of jazz does Metamorphic play?

KA: The pianist and band founder, Laura Cole, would say Kenny Wheeler, Moondog, Bjork, Radiohead, Keith Jarrett and many more. And we are doing some recording this year as well — I can’t keep up with it!

TM: I’m at a loss for words. Your projects are so various. Is this something true for your generation? Or is it just your path?

KA: There are lots of people in my age group who are doing a lot of different musical activities. I could name my friend Laura Moody, who is the cellist in the Elysian Quartet, but who has developed solo leftfield pop for cello and voice, and also plays cello in the West End. Gabriel Prokofiev is another — he’s a DJ, a contemporary classical composer, a producer — he produces a grime artist called Lady Sovereign who is on the UK’s celebrity Big Brother at the moment.

I don’t know if it is because you have to be multi-disciplinary these days to be successful, or just because you simply enjoy being that way. I just love all sorts of music, and slowly over the last ten, fifteen years I have been finding my way through that. You just keep following your path until another opportunity appears, and then you follow that one, and you might have a few paths you are going down in the end. I also think that it is practical as a professional musician today to have fingers in lots of pies — you never know what will take off and won’t.

TM: This seems immensely different from the generation of Birtwistle and Davies.

KA: Birtwistle hates pop music!!! He hates it! [laughs]. It is a different generation. There is a problem with kids not being exposed to any classical music or creative music making, or at least hardly any. Birtwistle and Maxwell Davies came out of a time when they did do a lot of that in school, and that’s fantastic.

It’s just the way the world is. You are exposed to so much music. I have the shortest attention span. I can listen to half a track on MySpace and say “yeah. Next! Next!” But I think it’s awful to damn pop music. Most people listen to just pop music, and there’s a reason for that. Lots of it is really great, and gets you going [looks serious and nods head] or [mock-cries] or [dances] or a doing bit of all of those. You shouldn’t dismiss it.

TM: You mentioned no string quartets, and I presume there’s no solo piano music from your pen yet. Do you see moving in that direction at some point, or is that of no interest?

KA: It would be of interest….I did a lot of vocal music at university, and it’s been like a stone gathering moss as it rolls downhill. I often regret that I haven’t, alongside that, been writing loads of orchestral works and chamber music…but that’s just the way it is! If a string quartet asked me to write one, then I would!

Some of the music that I have written for DOLLYman would fit happily into a contemporary classical music concert, so I have made my own opportunities, I suppose. I would love to write more theatrical works, and ask instrumentalists to be part of that.

TM: If you look ten years down the road, where would you see yourself, musically?

KA: I would hope that all of the things I am in involved in at the moment were ten times as successful as they are now.

TM: Who would you like to have commission you?

KA: I have become so used to linking performance and composition that just thinking of myself solely as a composer can be hard… The absolute ideal would be Bang on a Can All-Stars, because they are interested in the sort of music as I am. The Elysian Quartet. I would almost be more interested in being commissioned by the fantastic Scandinavian pop group Efterklang, or Antony Hegarty, or Björk — people interested in the outer limits, but still within pop music.

TM: Are there other activities you would like to mention?

KA: Keeping up with tradition of Britten, Maxwell Davies and co, I do a huge amount of educational and community work. This is both as a workshop leader, performer and composer, with organisations like Wigmore Hall, Trinity College, Drake Music, Creative Partnerships, Live Music Now and others. It feels valuable, and it’s good to be delivering some high-quality musical experiences to kids.

I also curate an occasional experimental vocal night, Gobsmack, in London, through the music networking organization Music Orbit. And I’m a keen blogger — both on my own cultural life (http://de-composing.blogspot.com) and sporadically on football (www.feverbitch.com)!

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Kerry%20Andrew%20%282%29.png image_description=Kerry Andrew

product=yes producttitle=An Interview with Kerry Andrew productby=By Tom Moore

War and Peace at the Theatre Royal, Glasgow

By Richard Morrison [Times Online, 25 January 2010]

It was a British opera company — Sadler’s Wells, in 1972 — that presented the first complete staging of Prokofiev’s Tolstoy adaptation. Now a remarkable Scottish-Russian collaboration has led to the world premiere of this epic masterpiece in its original version. And it is startlingly different. Where is the ear-splitting choral roar that usually opens the work? Or those tractor-thumping anthems to indomitable Russian peasants and their saintly leaders?

Dido and Aeneas by Les Arts Florissants

Producers of opera certainly wish it, for they turn to Dido all the time, in every sort of production and circumstance. Dido, brief and elementary as it is, is a complete work, even “grand” (as William Christie suggests in this DVD’s supplemental film), in the range of emotions it takes us through, the completeness of the story we are asked to feel, the “Shakespearean” variation (as director Deborah Warner suggests in the same film) between heroic tragedy and madcap humor. Dido repays every sort of effort, from amateur to elitist.

Les Arts Florissants are more familiar from their grandiose productions of such works as Lully’s Atys, Charpentier’s Medée, Rameau’s Les Boréades and Monteverdi’s Il Ritorno di Ulisse, but Dido might have almost been composed with their gracious style in mind. Deborah Warner’s production plunks the characters down in a girls’ school (the site of Purcell’s original commission), and leaves the girls such duties as mimed history, shrieking courtiers, masked demons and so on, which they acquit with brio. An inserted prologue presents actress Fiona Shaw reciting (and enacting) Ted Hughes’s version of “Echo and Narcissus” and some bits of Eliot and Yeats on love affairs gone awry, just to put us in the mood for Arcady and broken hearts in lieu of an overture. (Purcell’s, if it ever existed, is lost.)

What follows is always delicious to watch: muscular tumblers writhing together while suspended from the ceiling represent a visible thunderstorm, the sorceress demonstrates her evil by puffing a cig, while her goth attendants snort cocaine in Madonna lingerie, the “spirit” they invoke gives Aeneas’s valet a talking seizure, and Dido takes poison and goes blind, reaching for Belinda’s hand, and fading away in her arms. The set is classic, court and pool and glade, against a shimmering curtain of metallic beads, filmed in Paris’s sumptuous — but not dauntingly enormous — Opéra-Comique.

Delicious too the performances: Malena Erdman’s delicate Dido, each phrase sweet with ardor or drawn out in pain, bustling Judith van Wanroij’s Belinda the motherly confidante, Christopher Maltman’s robust (if sometimes wobbling) Aeneas, Hilary Summers’s louche and envious Sorceress. The English diction of this international company is exceptional: you won’t need titles, even for the choruses. An orchestra of twenty ranges emotionally over the cues of Purcell’s music and Tate’s libretto.

The supplementary film interviews Christie (in French) on the edition of Purcell used and where and why enhanced or revised (it is unclear whether the score as we have it is complete, or exactly when or why it was composed), Warner (in English) on her inspiration from the girls’ school idea and the body of “Arcadian” myth and poetry that Purcell’s audience would have known, but requires a refresher for most modern viewers — so that she and Christie and Fiona Shaw came up with the classically referenced prologue and other references within the staging, to Dido’s earlier widowhood, to Troy’s fate, to Rome’s destiny, and to Diana and Actaeon.

John Yohalem

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Dido_FRA.png image_description=FRA Musica FRA 001 product=yes product_title=Henry Purcell: Dido and Aeneas product_by=Malena Ernman (Dido), Judith van Wanroij (Belinda), Hilary Summers (Sorceress), Céline Ricci (First Witch), Ana Quintans (Second Witch); Christopher Maltman (Aeneas), Marc Mauillon (Spirit), Damian Whiteley (Sailor). Prologue: Fiona Shaw. Les Arts Florissants, conducted by William Christie. Directed by Deborah Warner, sets and costumes by Chloe Obolensky. Produced by Opéra Comique in cooperation with De Nederlandse Opera and des Wiener Festwochen. Film by François Roussillon. Supplement: A vision of Dido and Aeneas, with William Christie and Deborah Warner. FRA Musica and Opéra Comique. 66 minutes, subtitled. Film: 23 minutes. product_id=FRA Musica FRA 001 [DVD] price=$26.99 product_url=http://astore.amazon.com/operatoday-20/detail/B002QXI2N6January 24, 2010

Opera review: Long Beach Opera stages 'Good Soldier Schweik'

By Mark Swed [LA Times, 24 January 2010]

Robert Kurka’s “The Good Soldier Schweik” is a sassy opera. Long Beach Opera is a sassy company. So there was never need to wonder whether this plucky American cult opera from the 1950s should suit the American opera company known for its profuse pluck. Of course it did Saturday night in an entertaining production at Center Theater of the Long Beach Performing Arts Center that will be repeated in Santa Monica on Saturday.

January 22, 2010

Fischer, NSO mine the beauty in 'Das Lied von der Erde'

By Anne Midgette [Washington Post, 22 January 2010]

The tenor begins with a drinking song and ends with a drinking song. The mezzo-soprano begins and ends with one of the most haunting oboe melodies in the orchestral literature.

Il Mondo della Luna (The World on the Moon)

Haydn is often considered the father of the symphony, the string quartet and the piano sonata, but he is seldom mentioned in an operatic context. That’s not because he wasn’t any good at it — he was often very good. But he was seldom consistently good at opera, and he never found — or sought, maybe — the sort of mature libretto that would display his talents as Lorenzo da Ponte displayed those of Mozart, Salieri and Martin y Soler. Haydn’s operas seem a series of amiable misfires with charming moments — but I’ve only attended seven of them, and none were his grand operas, Armida and Orlando Paladino, which may play differently.

As the operatic world scours forgotten and therefore fresh scores, Haydn, a familiar name, is bound to seem appealing even without Maria Theresa’s imprimatur (“Whenever I want to hear good opera, I go to Esterhàza,” she said, probably as much to goad the management of her court theater back in Vienna as to compliment her host). Haydn’s style is familiar to us, all modern opera singers being trained to perform Mozart, and the forces required are seldom large.

Carlo Goldoni, librettist

Carlo Goldoni, librettist

Il Mondo della Luna, using a popular libretto by Goldoni that was

set by everyone from Galuppi to Paisiello, is a typical buffo tale of a rich

old fool, Buonafede (“good faith”), opposed to the marriage of his

two daughters and their maid to the three impecunious men they love, with the

sly twist that the old coot has a hobby: astronomy. One of the boyfriends,

Ecclitico (“ecliptic”), is a charlatan astrologer who pretends to

transport the old boy to the moon. Buonafede, presented to the lunar emperor,

is dazzled by Lunatic mores and court etiquette (Maria Theresa probably loved

this part), but he regrets his womenfolk are missing the fun. Quicker than you

can say, “May the farce be with you,” they arrive! — beamed

by transporter, one presumes. The emperor marries the venal maid, Lisetta, and

his chamberlain and master of ceremonies wed the two daughters. Wedding hymns

are sung in the Lunatic tongue. Buonafede is puzzled that the girls already

speak it so well, and though furious when he learns he has been bamboozled,

accepts the fait accompli. In the full libretto, he reflects philosophically

that you really need to travel to get the right perspective on life back home

— but the moral was one of Gotham Chamber Opera’s omissions.

Gotham has created one of the more dazzling entertainments of the New York season by presenting this nonsense in the Hayden Planetarium at the Museum of Natural History, replete with instrument panels, space suits (the elegant and witty costumes are by Anka Lupes), globular space helmets, acrobatic “moon nymphs” and above it all, on the 180-degree dome, shooting stars, exploding galaxies, shots of earth and the moon, and the wildest light show since psychedelia fell from fashion. Viewers of a certain age (mine) may recall The Saint in its heyday, but the music was better at the planetarium and the show a lot shorter. The whole run has sold out, and it’s hard to imagine anyone attending who would not gladly go again.

The one exception I would take is, in fact, to the evening’s brevity. Over-anxious not to bore, music director Neal Goren and director Diane Paulus may have left too much out. Over half the opera was omitted — on the grounds, Goren says, that the cuts were less than top-drawer Haydn. That may be true, and no one wants more secco recitative “dialogue” than we absolutely need, but confining most of the singers to one aria apiece means the characters are one-dimensional, silhouettes of slight interest or humanity. You cannot tell the sisters apart, for one thing — from the synopsis in the program, I’m not sure which one marries which lover — and you do not know or care if their feelings are sincere. In a farce, someone ought to want something sincerely or the crazy shenanigans aren’t as funny; there’s no contrast. You need Kitty Carlisle as a backdrop for the Marx Brothers.

In Il Mondo della Luna, Gotham goes for constant entertainment rather than letting the drama merely rest, at any point, upon the skills of the singers, the beauty of the often wonderful music. This is a current trend, and those of us who like singing may find that, fun as it is, it can go too far in an MTV direction. On the plus side, it sure was fun.

It would be difficult to single out any performer among the seven flawless players of this ensemble cast. Marco Nisticò seemed to be enjoying himself as the bubbling blowhard Buonafede, and he had the most to do, swinging hips as he ornamented his arias. Nicholas Coppolo gets special notice for being so slimy a phony as Ecclitico and then leaping seamlessly into the role of ardent lover to sing a rapturous duet with his Clarice (Hanan Alattar — or was it Flaminia, Albina Shagimuratova? Well, each one had an aria, and both were excellent). Rachel Calloway, as pert Lisetta, demonstrated the swagger of a chambermaid is exactly the right style for an empress. Timothy Kuhn sang an alluring love song to himself — director Paulus’s idea, not Haydn’s, but charming in context, and Matthew Tuell triumphed as the spunky valet who ascends to the lunatic throne. This was far and away the best all-around cast I have encountered in a Gotham production, each of them worthy at the very least of another aria or one of the omitted da capos. They were also all Lucy-ready farceurs — though a very little “disco” dancing in eighteenth-century costume goes a long way, and after an hour of it one wondered if director Paulus had run out of ideas or was simply bored by the characters. The Gotham orchestra played music that was always pleasant and sometimes heavenly.

Impossible to discuss the event and not mention Philip Bussmann, credited with Video and Production Design, who made a charming evening a spectacular one. And the Gotham team for dreaming this up, and the Museum of Natural History for recognizing a major opportunity when it came their way.

John Yohalem

image=http://www.operatoday.com/IL-MONDO-Photo-1-small.gif image_description=Nicholas Coppolo and Hanan Alattar [Photo by Richard Termine courtesy of Gotham Chamber Opera] product=yes product_title=Franz Joseph Haydn: Il Mondo della Luna (The World on the Moon) product_by=Clarice: Hanan Alattar; Flaminia: Albina Shagimuratova; Lisetta: Rachel Calloway; Ecclitico: Nicholas Coppolo; Cecco: Matthew Tuell; Ernesto: Timothy Kuhn; Buonafede: Marco Nisticò. Gotham Chamber Opera at the Rose Center Planetarium, American Museum of Natural History, conducted by Neal Goren. Performance of January 20. product_id=Above: Nicholas Coppolo and Hanan Alattar [Photo by Richard Termine courtesy of Gotham Chamber Opera]Respighi — Works for solo voice and orchestra

Among his works for solo voice and orchestra, are settings of texts by the English poet Shelley, Aretusa [“Arethusa”] (1910-11), and La Sensitiva [“The Sensitive Plant”] (1914). (Respighi composed a third piece with a text by Shelley, Il Tramonto [“The Sunset”], a work with string quartet, even though it is sometimes performed by string orchestra, but it is not included in this recording.)

This recording of La Sensitiva is an engaging piece because of the florid vocal line and the evocative accompaniment. The sonorities are reminiscent of some of his tone poems, with solo wind timbres and richly scored strings. As full as the orchestra can be, Respighi never allows the scoring to obscure the voice, and in this recording Damiana Pinti offers a fine reading of the text. Her voice is resonant and textured, as the singer uses various shadings to color the line. As clear as her middle and lower registers are, Pinti has a clear and even upper range, which serves the piece well. Moreover, in the sustained passages, Pinti’s tones have a fine shape, which underscores her carefully enunciated text. While Respighi is known for his instrumental piece, those familiar with his music may wish to hear this vocal setting, which serves Shelley’s text well, which is served well through its translation into Italian. Yet the accompaniment not only supports the voice in this piece, but reinforces the mood and sense of the text. If some aspects of Respighi’s programmatic music emerge in this work, it is not unwelcome, but certainly another means of appreciating this extended piece for solo voice and orchestra.

A similar piece, Aretusa, is equally colorful, as the orchestral accompaniment serves to reinforce the meaning of the text. These somewhat programmatic gestures offer some contrast to the relatively declamatory vocal line. Pinti offers as expressive a reading of Aretusa as she does in La Sensitiva. Here, here the sometimes rich and dark shadings are impressive, and Pinti is good to shape the line through her pacing and dynamics; likewise, Marzio Conti provides solid leadership of the orchestra. With music like this, where the accompaniment intersects the vocal line, the clean entrances and precise releases are crucial to executing the pieces well.

The other work on this disc is the ballet La Pentola Magica (1920), one of the composer’s five ballets, the best known being La Boutique Fantasque, (1918), which is based on music originally composed by Gioacchino Rossini. La Pentola Magica, translated as “The Magic Plot” is work in two parts, which conveys a fable about a Russian princess who longs for a handsome young prince to relieve her of her boredom. Despite attempts to entertain the princess, she is enchanted by the song of a Russian peasant. The peasant dances around a purportedly magic pot, and the princess wants it, since it appears to have supernatural properties. Ultimately the peasant will surrender the pot for kisses from the princess. The court astrologer shows the czar what is happening, and he throws a shoe at his daughter. Yet after she repulses the peasant, the peasant reveals himself as a handsome prince, and the work ends with the princess weeping for her loss.

La Pentola Magica contains some engaging music, not only in its evocation of the Russian court, but also in the entertainments for the princess, as found in the dance of the Armenian slave. Respighi used the opportunity to create some colorful episodes. While Respighi makes use of chromaticism, his harmonic structures remain solidly tonal; dissonances occur, sometimes to offer some color, but the music is never atonal.

All in all, the three pieces found in this recording offer a different side of Respighi than found in the more familiar tone poems about Italian subjects. While it is possible to find some contrast to those tone poems in the suites of Ancient Airs and Dances, the settings of poetry by Shelley are good examples of Respighi’s vocal writing. At the same time the ballet La Pentola Magica demonstrates yet another side of the composer’s musical imagination, which is given a convincing interpretation by Conti and the Orchestra Sinfonica del Teatro Massimo di Palermo. The sound on the CPO recording is clear and distinct, and this supports the colorful scoring that characterizes Respighi’s music.

James L. Zychowicz

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Respighi_Pentola.gif image_description=Respighi: La Pentola product=yes product_title=Ottorino Respighi: La Pentola Magica, La Sensitiva, Aretusa. product_by=Damiana Pinto, mezzo soprano, Orchestra Sinfonica del Teatro Massimo di Palermo, Marzio Conti, conductor. product_id=CPO 777-071-2 [SACD] price=$16.99 product_url=http://astore.amazon.com/operatoday-20/detail/B000GQL8O0January 21, 2010

Netrebko and Hvorostovsky, Royal Festival Hall, London

By Richard Fairman [Financial Times, 21 January 2010]

It has been a very odd winter for celebrity concerts in London. There was Cecilia Bartoli flouncing around in velvet breeches pretending to be a castrato, Bryn Terfel whip in hand as the devil, Angela Gheorghiu trailing a little-known Romanian tenor and a fleeting appearance by Renée Fleming that was over almost before it had begun.

Monteverdi, 1610: Vespers to Usher in the Baroque

By James R. Oestreich [NY Times, 21 January 2010]

As Monteverdi’s magnificent 1610 Vespers gathers momentum in its inexorable march through a big anniversary year, it quickly becomes evident that comparisons, however odious, are inevitable. This vast canvas from the dawn of the Baroque — formally, the “Vespro Della Beata Vergine” (“Vespers of the Blessed Virgin”) — offers such a rich ground for competing scholarly views and conjecture that performances differ radically, one shedding light on another.

January 20, 2010

Norma, Théâtre du Châtelet, Paris

By Francis Carlin [Financial Times, 20 January 2010]

Meet Amy Winehouse’s double as she joins her friends at the Charenton asylum and gives Norma the Marat/Sade treatment.

January 19, 2010

For Verdi, Masquerading as a Baritone

By Anthony Tommasini [NY Times, 19 January 2010]

In 1959, when he was 18, Plácido Domingo auditioned for the National Opera in Mexico City as a baritone. The jury was impressed but told Mr. Domingo that he was really a tenor. Two years later he sang his first lead tenor role, Alfredo in Verdi’s “Traviata” in Monterrey. And so began one of the great tenor careers in opera history.

Simon Boccanegra, Metropolitan Opera, New York

By Martin Bernheimer [Financial Times, 19 January 2010]

Most singers spend their autumnal days pasting carefully censored clippings into their scrapbooks and boring their grandchildren with exaggerated tales of distant triumphs. Domingo, who celebrates his 69th birthday tomorrow, knows nothing about resting on laurels. In fact, he knows nothing about resting.

Operatic Italian

Pulling operatic libretti from Mozart to Verdi, Thomson introduces the student to word-for-word translation, grammatical concepts, and the natural pronunciation and cadence of the language, while unfolding this intricate language in a practical and applicable manner.

Thomson’s main premise for using libretti as source material is that the language of the libretto is filled with literary, poetic and old-fashioned vocabulary devices. The current language learning paradigm found in university language courses aims to teach the student vocabulary and grammar to survive and thrive in that particular modern country. Basic themes include food, travel, and paying for a bus ticket. While practical information for the average Italian learner, music students would be hard-pressed to find an opera entitled Dovè la mia valigia? with which to apply this knowledge.

Operatic Italian is well organized and direct, introducing each libretto example with it’s corresponding musical score, IPA translation, English word-for-word translation, and marked accents for atypical words. Thomson’s goals for the student are to 1) recognize parts of speech 2) understand verb tenses and their functions 3) develop an understanding of grammar peculiarities found in literature. Chapter topics of particular interest to the music student include pronunciation and developing an Italian accent, understanding what is lost in translation from Italian to English, what to appreciate in libretti, and Dante’s influence on Italian literature (opera libretti included).