April 28, 2010

The Power of Powder: Thomas Adès at the Royal Opera House, London

In 15 years, Powder Her Face has gone from new music cult hit to an opera of international significance. The Tempest notwithstanding, it’s Adès’s finest work. He’s gone on to fame, fortune and Los Angeles, but hasn’t quite recaptured the vitality of his early work. More recently, he’s revisited Powder Her Face, writing a suite based on it, so maybe that will reinvigorate his creative juices.

So cherish this wonderful production directed by Carlos Wagner. The production is every bit as much of a star as the Duchess of Argyll, who inspired the opera in the first place. In 1963, she appeared naked, but for a string of pearls, in photos which caused a scandal, because she was performing on naked men (one of whom was later revealed as Douglas Fairbanks Jr.)

“In your face” is probably an indelicate term to use in the circumstances, but it describes the magnificent staging well. There’s no way round the fact that the Duchess was destroyed by hypocrisy. In the small space of the Linbury Studio, Conor Murphy’s giant staircase overwhelms, but that’s the point: there’s no escape! It’s a brilliant piece of theatre in itself, because it changes character in each scene. In the end, Paul Keogan’s lighting turns it into a lurid neon sunset, the perfect coda to the Duchess’s life.

Rebecca Bottone as Mistress

Rebecca Bottone as Mistress

The stairs also mean the cast can go up and down using the whole performance space, overcoming the cramped limitations of the small stage. Perhaps that’s a reverse metaphor for the Duchess, too. With her wealth and beauty she could have lived a charmed life, if she’d conformed. Instead she grabbed life greedily, imbibing to the full. The headless men in the notorious photos got away scot-free, as did the philandering, brutish Duke, but the Duchess’s reputation was destroyed. Defiant to the end, she cocoons herself away from a world that’s changing in ways she can’t understand (“Buggery, legal?” she exclaims.) Her end is sordid, but she keeps her dignity, at least in delusion. Larger than life personalities just don’t fit in grubby society.

The music’s remarkably inventive. Saxophones and jazzy clarinets evoke the glamour of 1930’s London. “They don’t know how to do parties now,” she wistfully tells a young reporter. Adès’ does luscious elegance, but undercuts it with sharp, dissonant edges. The luxury is illusion. Debutante balls were a meat market for the upper classes, nothing romantic. The Duchess buys sex from a waiter. “You can get anything with money,” she cries. But others have more money, and more power. The Courts condemn her, to the prurient delight of the “lower” class, represented by Bottone and Paton in dirty macs. And when the money runs out, the Duchess is evicted.

Iain Paton as Waiter and Joan Rodgers as Duchess

Iain Paton as Waiter and Joan Rodgers as Duchess

Adès weaves elusive sounds into his orchestra. At the beginning of the second Act, he starts with solo accordion, played in a mysterious, bluesy fashion.. It makes an excellent bridge between past and present. Later, accordion, harp and piano (Adès’s instrument and “voice”) combine, wheezing, wailing and tensely staccato percussive blasts. It’s surreal, like hearing the ghosts of the past dancing in Hell. At the end, sinister cracks and whirrs are heard. They’re the sound of fishing rods being reeled in. Like a fish, the Duchess has been caught and dies.

The opera is both diamond hard and brittle, but then, that’s the subject. The Duchess wasn’t a nice person even though she was a product of the circles she moved in, and the men around her are worse. Her sexuality is compulsive, and fundamentally unerotic. (It’s the role, not Rodger’s portrayal, which is superb.) Perhaps the maid gets more fun. Bottone’s high-pitched shrieks at the top of her register (an Adès’ trademark) are well deployed. She’s the voice of anarchy. Her voice rips apart the silky surface of propriety.

Anne Ozorio

image=http://www.operatoday.com/%C2%A9BC20080607158-JOAN-RODGERS.gif image_description=Joan Rodgers as the Duchess [Photo by Bill Cooper courtesy of the Royal Opera House]

product=yes

producttitle=Thomas Adès: Powder Her Face

productby=Joan Rodgers: the Duchess, Alan Ewing, Iain Paton, Rebecca Bottone (multiple roles), Timothy Redmond (conductor), Royal Opera House Orchestra and guest artists. Carlos Wagner (director), Conor Murphy (designs), Paul Keogan (lighting) Tom Baert (choreography). Linbury Studio Theatre, Royal Opera House, London. 26th April, 2010.

product_id=Above: Joan Rodgers as the Duchess

All photos by Bill Cooper courtesy of the Royal Opera House

April 27, 2010

Floyd’s Susannah in Boston

Susannah is an opera in two acts by American composer Carlisle Floyd, who wrote both the libretto and music. The story is very loosely based upon the story of Susanna and the Elders found in the Apocrypha. In the biblical story, Susannah is found bathing naked by two elders. They threaten to claim she is unchaste unless she agrees to have sex with them. Susannah refuses, is subsequently arrested and about to be put to death, when the prophet Daniel appears and proves her innocent.

Floyd’s version is much darker and leads to tragedy. He updated the story to the mid-twentieth century backwoods of Tennessee. Susannah Polk is an 18-year-old innocent girl who lives with her oft-drunk brother, Sam. When she is discovered innocently bathing naked in the woods by the Church Elders who are looking for a new baptismal site, they and their wives accuse her of being a sinner and pressure Little Bat McLean, her young friend, to lie and say that he was seduced by her. At a revival meeting, Olin Blitch, a traveling preacher, is unsuccessful in getting her to repent. He follows Susannah to her home to continue asking her to repent, but he ends up pressuring her into sex. Now knowing that Susannah was a virgin and that the charges against her are false, Blitch tries to persuade the townspeople to forgive her, but they refuse. Susannah’s brother Sam returns home. After he discovers what has happened, he kills Blitch and runs away. The townspeople try to force Susannah to leave the valley, but, rifle in hand, she drives them off. Only Little Bat remains. Susannah pretends to try to seduce him and then pushes him away.

Susannah premiered at Florida State University in 1955 with Phyllis Curtin in the title role. After many performances in America and abroad, it finally received its Metropolitan Opera premiere in 1999. Today, Susannah is second only to Porgy and Bess as the most performed American opera. It likely has entered the permanent operatic repertory. It is easy to see why. Floyd refers to his works not as operas but as music dramas. Fortunately, Floyd’s talent as a writer is equal to his talent as a composer. The end result is a perfect fusion of word and music that is universal, timeless, powerful and beautiful.

Adam Canedy as Olin Blitch.

Adam Canedy as Olin Blitch.

In mid-April, Floyd reunited with Curtin to be in residence when Boston University School of Music and School of Theater mounted a new production of Susannah. The two met and worked with students, took part in portions of the rehearsal period, and held pre-show discussions before the first two performances.

Although both are now well into their eighties, age has not diminished their acumen. It was also more than a “do you remember when” experience. Their comments were illuminating with Floyd, in particular, showing himself to be strongly opinionated.

In discussing the gestation period of the opera, Curtin recalled how Floyd had come to her with portions of the partially completed score to ask if she would be willing to sing the part so as to advance possible production of the work.. At that time, Curtin had the more established career. Curtin said that she readily agreed as soon as she saw the music. She also said “I had just finished performing Salome so I knew how to play a bad girl.”

Act II, Scene 5 - Susannah facing down the mob.

Act II, Scene 5 - Susannah facing down the mob.

Curtin also recalled how, in the late 1950’s, she went to Floyd and asked him to write a concert piece for her. Floyd responded by writing an aria based on a chapter from Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights. Curtin said that after the concert at which she sang the aria, the first thing asked was where is the rest of the opera. The end result was that Floyd then had to write the complete opera.

It has long been speculated that Floyd wrote Susannah in response to the McCarthy led witch hunts against communists and subversives in the 1950s — an operatic equivalent of Arthur Miller’s The Crucible. Floyd has always denied this, but in the question and answer sessions preceding the performances he softened his position. While continuing to deny a direct connection, he went on to say that, in writing Susannah, he obviously was subliminally influenced by the climate of fear generated during the McCarthy era. He then spent several minutes describing the reign of terror that descended upon Florida State University during this period, of the campus committees set up there and elsewhere to insure “correctness”, and how even the slightest suspicion was enough to destroy a career.

Floyd also revealed for the first time that he didn’t read the biblical story of Susannah until several years after he completed the opera. He said that he just took the short summary of an idea that a friend proposed as the possible subject for a new opera and went from there entirely on his own.

When asked why he had always written his own libretti, Floyd replied that that was the only was he could assure that he had total control as to the outcome of the work. He also said that writing the libretto was the more difficult part of the process — one that had become even more difficult for him in recent years, as a result of which he was currently not composing.

When questioned as to whether or not he had gone back and re-written any of his operas or if he wanted to, Floyd replied that, with the exception of one opera that was completely re-written for a specific purpose, he had never re-written or desired to re-write any part of his operas. “Why should I?” he said, “I’ve said everything that I want to say before I release a work for performance.” He also quoted Verdi who, during the difficulties he was experiencing in revising Simon Boccanegra, said to the effect that “When you rewrite your work it’s difficult not ending up with a five-legged stool.”

When asked what had surprised him the most since the debut of the work, Floyd referred to the role of Olin Blitch. “When I saw Mack Harrell in the role, I didn’t think that it could ever be played in any other way. I subsequently discovered that the role can be played in many ways.”

When Floyd was questioned as to what advice he would give to sopranos who sing the role of Susannah, he paused for a few seconds before saying “Don’t exhibit any self-pity. So much happens to Susannah during the course of the opera, the audience will fully be with you without your help.”

The Boston University production of Susannah double cast the roles of Susannah and Olin Blitch, with the remaining roles single cast. All are students at B.U. Soprano Chelsea Basler and baritone Adam Cannedy headed the second evening’s cast.

Chelsea Basler was simply superb in the title role. Floyd makes great demands of any soprano singing the role. The music of the opera appears deceptively simple but it is not. At times very lyrical in nature, at other times the brass and woodwinds dominate the music. Consequently, you need a soprano who can not only spin the lyrical lines and pianissimos of “Ain’t It a Pretty Night?” in Act I but also be able to shout down the mob in Act II. Basler met all of the musical demands of the role. She was also a singing actress, effectively portraying Susannah’s journey from the young, free spirit portrayed at the start of Act I to the embittered woman she is turned into by the end of Act II. Particularly noticeable was the intensity with which she approached the role. Her reaction to her persecution was simply heartbreaking.

Adam Cannedy made an effective Olin Blitch, with a sonorous and secure voice. The role was deliberately underplayed, making Blitch a more human figure as against a Burt Lancaster “Elmer Gantry” type. It is difficult to cast young baritones in this type of role as they won’t mature vocally for several more years. Also, in a role that has been defined by such singers as Norman Treigle and Samuel Ramey, putting a young singer in this role is like asking a 26-year-old actor to play Macbeth. Cannedy came close to meeting these challenges.

Clayton Hilley acquitted himself with full honors in the role of Sam, Susannah’s brother. He has a gorgeous tenor voice that was used to full effect. He also was successful in accomplishing the difficult task of portraying a character who is drunk most of the time he is on stage without turning into a caricature. The surprise of the evening was Omar Najmi portraying Little Bat McLean. Only a first year Master’s student at B.U., he gave a very strong, secure vocal performance while at the same time, from an acting standpoint, effectively communicating that Little Bat is mentally challenged.

The Boston University Chamber Orchestra was conducted by William Lumpkin. With thirty-seven members, I don’t know why it is called a “chamber orchestra.” The first performance indicated that the orchestra needed one more rehearsal. The orchestra was in secure form for the second night.

Sharon Daniels, who is Director of Opera Programs and the Opera Institute at Boston University, directed the production. A former soprano who sang the role of Susannah several times including twice with the composer as stage director, she was the one responsible for bringing Floyd and Curtin to B.U. for this production. Under Daniels’ direction, every singer, singing not only in English but in dialect, could be clearly heard and largely understood while on stage. The chorus was not a chorus but a group of townspeople, each not only having its own character but re-acting as to what is going on on stage. Daniels has long had that great ability to portray individuals on stage as real people in natural situations and not as actors or singers performing before the public. Daniels is both a major and unique talent who should be directing in much larger opera venues.

Credit must also be given to the student production team for the success of the performances. Many of today’s scenic designers meet Susannah’s challenge of ten scenes in two acts by giving audiences near empty stages decorated with a few pieces of ribbon and twigs. Scenic designer John Traub instead directly confronted the challenge, creating a natural, woodland glen framing individual sets for each scene while at the same time allowing for the rapid scene changes that today’s audiences, condition by television and film, now demand. He was matched in talent by Costume Designer Elizabeth McLinn and Lighting Designer Mary Ellen Stebbins, the latter providing nuanced lighting that subtly directed the audience’s attention to what was going on on stage without the audience realizing that it was being led.

With the advent of Peter Gelb at the Metropolitan Opera and the series of productions that are being “updated” in New York and elsewhere to great controversy, there has been an increase in discussion as to whether opera or realistic productions of opera has any future in America. If other academic opera centers are performing at or near the level exhibited by Boston University in this endeavor, then opera and realistic opera productions both have a strong future in America.

One last comment. God must have a special love for retired sopranos. Although Phyllis Curtin has now passed four score and eight years, she remains a very beautiful woman.

Raymond Gouin

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Susannah_BU.gif image_description=Chelsea Basler as Susannah [Photo by B.U. Photography] product=yes product_title=Carlisle Floyd: Susannah product_by=Boston University College of Fine Arts at Boston University Theatre Mainstage product_id=Above: Chelsea Basler as SusannahAll photos by B.U. Photography

Smut and loathing in Powder Her Face

By Barry Millington [Evening Standard, 27 April 2010]

If for no other reason, Thomas Adès’s and Philip Hensher’s Powder her Face will go down, like the Duchess of Argyll herself, for an act of dubious taste. The first blow-job on the operatic stage is administered by the “Dirty Duchess” (sadly based on a real-life celebrity), servicing a waiter in her hotel room.

Il barbiere di Siviglia, Arizona Opera

It is the first play of a trilogy that includes La folle journée ou Le mariage de Figaro, which was made into the opera Le nozze di Figaro by Mozart, and La mère coupable, which was set by Corigliano as The Ghosts of Versailles. Over the years, various composers of operas and singspiels have used it as the basis of their compositions. Ludwig Benda and Johann André wrote music to it in 1776. Johann Elsperger based a singspiel on it in 1780. Composer Giovanni Paisiello and librettist Giuseppe Petrosellini made Le barbier into an opera and it appeared first in Russian translation at the imperial court of St. Petersburg in 1782.

In 1783, The Barber’s story appeared as Die unnützige Vorsicht, a translation of the subtitle, The Useless Precaution. In 1794, The Spanish Barber by British born composer Alexander Reinagle was sung across the ocean in the brand new United States. It is said to have been a favorite of George Washington. In 1796, Nicolas Isouard, an organist from Malta who had moved to Paris to compose, set the story to music and it was presented at the Opéra Comique. When Rossini and librettist Cesare Sterbini chose that story and premiered their opera in 1816, Paisiello’s fans heckled the performance. At the second performance, however, the audience realized that Rossini’s version was well worth hearing, and from then on it became at least as popular as Paisiello’s work, which was also played for many years.

On April 24, Arizona Opera presented the last opera of its 2009-2010 season, a rousing rendition of Gioachino Rossini’s The Barber of Seville, at Phoenix Symphony Hall. The traditional production was by Bernard Uzan with detailed and functional sets by David Gano. The costumes by Anna Bjornsdotter were flattering to the artists as well as correct for the time and place. With Artistic Director Joel Revzen in the pit with the excellent Arizona Opera Orchestra, everything was ready for a fine performance. The overture was played with clarity and translucence. It seemed that the players could go as fast as the wind and still play each note precisely.

Unfortunately, after the overture, and while the tenor was singing his most difficult first aria, ushers allowed latecomers into the hall and accompanied them with flashlight beams and whispers.

Tall, good-looking Brian Stucki is a wonderful new coloratura tenor who can sing the most graceful lines of Almaviva’s music in correct style. A good actor, he has all the essentials for comedic timing. As Rosina, Elizabeth DeShong sang with honeyed tones and quite a powerful voice. She also let the audience know from the beginning that she was not about to submissively obey her guardian, Dr Bartolo.

Elizabeth DeShong as Rosina, Peter Strummer as Bartolo and Joshua Hopkins as Figaro

Elizabeth DeShong as Rosina, Peter Strummer as Bartolo and Joshua Hopkins as Figaro

This was Joshua Hopkins’s first Figaro, but no one would have known it from his performance. He was an authoritative barber who sang with robust sounds and had both vocal and stage tricks up his sleeve. Bass-baritone Peter Strummer was thoroughly amusing as the self-righteous Dr Bartolo. His slow tones had polish. His patter was understandable and secure. As the conspiratorial Don Basilio, Kurt Link did not wear the traditional hat, but he was a great comic villain whose voice was redolent with colorful deep tones.

Grace Brooks was a Berta who thought both Dr Bartolo and Rosina were crazy. She is still in the AZ Opera Young Artist Program, but she is fast becoming a finished singer and her aria was a delight to hear. Although John Fulton did not have an aria, he portrayed both Fiorello and the Sergeant with thoughtful consideration of their situations.

The all male chorus led by Julian Reed sang with gusto and harmonized accurately. Reed also played the beautifully modulated recitatives on the harpsichord. This was a hilariously funny show and the laughter almost drowned out some of the music, but the Barber is a true comedy and it was good to see it so well appreciated by the Arizona audience.

Maria Nockin

image=http://www.operatoday.com/AZ_Barber_1%283%29.gif image_description=Brian Stucki as Almaviva and Elizabeth DeShong as Rosina [Photo by Tim Fuller / Arizona Opera] product=yes product_title=Gioachino Rossini: Il barbiere di Siviglia product_by=Figaro: Marian Pop (April 23, 25, May 2)/Joshua Hopkins (April 24, May 1); Rosina: Patricia Risley (April 23, 25, May 2)/Elizabeth DeShong (April 24, May 1); Almaviva: Victor Ryan Robertson (April 23, 25, May 2)/Brian Stucki (April 24, May 1); Bartolo: Peter Strummer; Basilio: Kurt Link; Fiorello: John Fulton; Sergeant: John Fulton; Berta: Grace Brooks; Notary: Cameron Schutza. Arizona Opera. Conductor: Joel Revzen. Director: Bernard Uzan. product_id=Above: Brian Stucki as Almaviva and Elizabeth DeShong as Rosina [Photos Tim Fuller / Arizona Opera]Towards the light: Juilliard students present Poulenc’s Dialogues

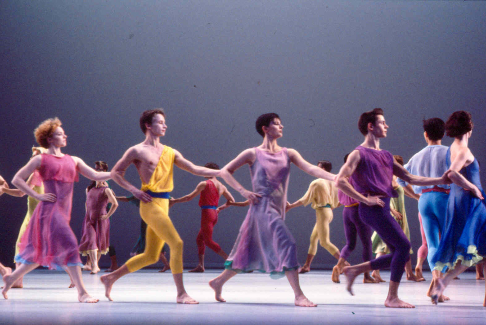

A dramatic swath of red fabric dominated the stage in the Peter Jay Sharp Theatre and the Juilliard orchestra, lead by Anne Manson, launched bravely into the action.

In the first scenes, set in the home of the Marquis de la Force in the midst of Revolutionary Paris, tenor Paul Appleby sang with great dramatic and musical impetus as the Chevalier de la Force. He sounded at ease singing in French and was among only a small number of the cast able to carry off Poulenc’s syllabic vocal setting with both fluid phrasing and a clear line reading of the text. As his father the Marquis, Timothy Beenken looked and sounded out of place. A truly terrible wig did him no favors and, as can only be expected in a student production, he simply seemed too green for the role. This was also the case with Tharanga Goonetilleke as his daughter Blanche.

In an opera full of compelling characters, Blanche is the most crucial because, by inhabiting both the outside world and the sanctuary of the convent, she becomes the lynchpin of the action and the audience’s proxy. (Furthermore, as Poulenc was famously called a half monk, half delinquent by the Paris press, she also serves as a surrogate for the composer himself.) Her intense fears and ultimate moral and existential dilemma should evoke empathy, not sympathy. Rather than seeming troubled or conflicted, Ms. Goonetilleke seemed mercurial or even coquettish. Blanche need not be likeable, but her moods must follow the psychology of Poulenc’s vivid orchestration. From her awkwardly timed entrance, it was clear that Ms. Goonetilleke, while a competent and attractive performer and singer, needs more time to develop the sensitivity required for this role.

Poulenc’s opera is filled with moments of dramatic prescience that parallel a building musical foreboding. To create a compelling momentum in this opera of short scenes and tableaux, it is necessary for these moments to be connected in a sort of symbolic storyline that is as crucial as the actual plot. For example, in the interview between Blanche and the Old Prioress, it must be made clear that Madame de Croissy has taken the young girl’s measure not because the older woman is prophetic, but rather because she identifies with Blanche and shares her fears. As the Prioress, Lacey Jo Benter sang and acted well but the impact of her death was lessened by the pallid approach to her first scene with Blanche.

All of the singers, not just Ms. Benter, suffered from director Fabrizio Melano’s choice to connect the various scenes and interludes by stringing them together without blackouts. At best this was awkward for the singers left onstage, but it occasionally had confusing consequences, especially in the instances where two scenes set months or years apart became effectively elided. Furthermore, because the lights remained on in between scenes, the audience sat and watched as Ms. Benter walked onstage and climbed into bed immediately before the death scene in which the Prioress asks if she might finally be well enough to sit in a chair, bedridden as she is with her fatal illness. Her death, which should be excruciating to watch, was therefore a little bizarre.

Such inconsistencies aside, many elements of Melano’s direction served the drama well. The red curtain was particularly inspired as it subtly evoked not only the typical theatrical curtain, but also a patriotic flag and even the guillotine itself. The beam of light used to delineate the convent from the outside world was visually arresting, and the intense glare from the stage right entrance produced silhouettes on the convent wall – clear physical projections of the worldly illusions mentioned in the libretto.

Among the rest of the student cast, Renée Tatum and Haeran Hong made strong impressions as Mother Marie and Soeur Constance, respectively. Tatum imbued her role as the Assistant Prioress with the required gravitas and she used all of Poulenc’s generous musical substance as inspiration for her subtle acting. Not only did Ms. Hong perform with the same musical style and charm she exhibited during the Metropolitan Opera National Council Audition finals, but she also portrayed a fully realized character from the moment she entered as the young novice. She exceeded expectations of any student and could easily perform the role in a professional production. Both her voice and her face have an angelic beauty and she appeared both brave and vulnerable in the opera’s crushing final moments, when Constance is left alone as a single voice at the end of the Salve Regina only to be joined by Blanche at the last second.

In the end, it speaks to the level of the students at Juilliard that the school is able to present such a complex, demanding opera. But it is an even greater testament to the quality of Poulenc’s opera that only rare performers can truly do it justice.

Alison Moritz

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Carmelites_Compiegne.gif image_description=The Carmelite Martyrs of Compiègne product=yes product_title=Francis Poulenc: Dialogues des Carmélites product_by=Tharanga Goonetilleke (Blanche de la Force); Paul Appleby (Chevalier de la Force); Lacey Jo Benter (Madame de Croissy); Emalie Savoy (Madame Lidoine); Renée Tatum (Mother Marie of the Incarnation); Haeran Hong (Sister Constance); Timothy Beenken (Marquis de la Force); Carla Jablonski (Mother Jeanne); Naomi O'Connell (Sister Mathilde); Javier Ernesto Bernardo (The Chaplain); Daniel Curran (First Commissary); Drew Santini (First Officer); Adam Richardson (M. Javelinot); Adrian Rosas (Second Commissary); Andreas Aroditis (Jailer); Timothy McDevitt (Thierry). Juilliard Opera and the Juilliard Orchestra. Conductor Anne Manson. Director Fabrizio Melano.April 26, 2010

Der Fliegende Holländer, New York

We must be grateful for what we can scrounge, and Der Fliegende Holländer, Wagner’s Weber-like romantic fable of the vampire-like sea captain doomed to sail till he meets the woman faithful to death, in August Everding’s outsize production, provides some sumptuous music-making. Holländer, indeed, has grown sufficiently unfamiliar to New Yorkers that many members of the audience were outraged to find they were expected to sit still for two and a half hours without intermission (though you’d have to go back nearly forty years to find a Met production of the opera that did include intermissions), and several of them walked out during the second scene-changing entr’acte.

Stephen Gould as Erik

Stephen Gould as Erik

The vocal standard of the evening was impressively high. Finnish

bass-baritone Juha Uusitalo, who has been singing Wotan around Europe, gave us

a suave, passionate Dutchman with a smooth, even, grateful sound. A tall man

and a fine actor, he was got up to look pale, raven-haired, huge of eye and

lofty of brow, rather like Wagner’s friend, King Ludwig of Bavaria

— appropriately; the king drowned.

Uusitalo would have been the star of the evening had not Hans-Peter König been singing the bumptious Daland. König has one of those godlike basses (think Matti Salminen or Kurt Moll), clear and even from top to bottom, enormous but graciously so, never oppressive, never bellowed, as gently nuanced as if he were singing lieder. You will think: if there’s a God, he sounds like this. It was the A-list performance of the night.

Stephen Gould, an American tenor who has been singing Siegfried in Vienna to great acclaim, made his Met debut as Erik. An enormous figure on stage, Gould has a voice as sturdy as his linebacker build and a clarion delivery, but has a tendency to hurl it out brusquely when romantic gentility seems called for, especially in this dreamy role. His bark was not harsh but it was unfinished — which seems right for the half-savage Siegfried but not for Erik. When he sang, one pricked up one’s ears — but when Mr. König sang, pricking up of ears wasn’t necessary — the voice came out into the theater and seduced us. Russell Thomas provided an energetic Steersman, seeming a bit small-scale in such company.

Deborah Voigt as Senta and Juha Uusitalo as the Dutchman

Deborah Voigt as Senta and Juha Uusitalo as the Dutchman

Deborah Voigt sang her first staged Senta. She looked good and hurled herself ardently about the room — at one point bringing the house to giggles, unintentionally one supposes: As Erik described his dream of the arrival of the Dutchman, she abruptly “assumed the position,” head back, legs spread, in anticipation. Her voice, though, was not in happy estate, stringy and unattractive for much of the night and occasionally flat. She nailed the “treu” on her final “treue als dem Tod,” but it was a bit late in the evening to rescue this heroic figure. Senta is a young girl with an earth mother coiled audibly within her, bursting out into thrilling cries. Senta — indeed Wagner — is not a good choice for Voigt’s instrument these days.

Hans-Peter König as Daland and Russell Thomas as the Steersman

Hans-Peter König as Daland and Russell Thomas as the Steersman

In the pit, Kazushi Ono, undeterred by occasional intrusive applause and the departure of those unwilling to do without intermissions, kept the oceanic rhythms of this nautical ghost story in driving motion. The only sounds one regretted were not in his department at all — the squeak of the metal gangway as it descended to the stage in Act I. It has indeed been years since its last use (seven by the story, ten at the Met), and we had an undesired squealing obbligato. This however had been oiled away by the final scene — good catch, Met crew!

John Yohalem

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Voigt_Senta.gif image_description=Deborah Voigt as Senta [Photo by Cory Weaver courtesy of The Metropolitan Opera] product=yes product_title=Richard Wagner: Der Fliegende Holländer product_by=Senta: Deborah Voigt; Dutchman: Juha Uusitalo; Daland: Hans-Peter König; Erik: Stephen Gould; Steersman: Russell Thomas. Metropolitan Opera chorus and orchestra conducted by Kazushi Ono. Performance of April 23. product_id=Above: Deborah Voigt as SentaAll photos by Cory Weaver courtesy of The Metropolitan Opera

Wagner’s Götterdämmerung and Schreker’s Die Gezeichneten

The program for Götterdämmerung omitted a credit for the role of Alberich (sung ably by Richard Paul Fink), requiring the inclusion of a slip of paper to amend the error. A larger inserted sheet advertised the upcoming three cycles of the Freyer production of Der Ring des Nibelungen, but the calendar of dates cited no month — time means little in the mythical world of Wagner’s masterpiece, one might propose.

Freyer is not an artist averse to rough edges, so these managerial slips would probably just amuse him. After all, as Brünnhilde sent the ravens off to Valhalla to tell Wotan of the end of his world, on Freyer’s set the raven cut-outs, located at either end of the stage lip, rose up to reveal two prompters, chest-high, backs to the audience but scores before them. Not long before that, a computer malfunction left the projected backdrop strewn with line after line of computer gibberish, but since one line of that was a time clock running down, perhaps it was part of Freyer’s design all along.

If Freyer’s climax disappointed (which it did), it wasn’t because of these intentional or inadvertent glitches, but because his invention did not match the boldness and incision seen in the earlier parts of this long, long show (and most of his other stagings of the Ring operas). Gibichungs on wires tumbling through the air behind a scrim of flames came off as more Cirque du Soleil than riotous or avant-garde. To the vociferous critics of Freyer’s work, it must be said that the mythic ponderousness seen in most stagings of Wagner’s work — a quality that those critics would insist is embedded in the libretto — holds little interest for Freyer. His vision is centered on identity, the no-man’s-land distance between what each character thinks of him or herself and what events reveal the truth to be. Thus, Freyer created the painted cardboard facades that characters carried before them, right from Das Rheingold until the end of Götterdämmerung. At that end, Linda Watson’s Brünnhilde couldn’t take the subterfuge anymore, and knocked not only her own flat representation to the ground, but those of the other characters then on stage. She had truly learned contempt for the ring, and the limitless avarice and ambition it inspired.

Surely Freyer’s sense of humor traumatized those most offended by his staging, especially the portrayal of Siegfried, a muscle-bound doofus who, nonetheless, came off as the only genuine, likable figure in the world. John Treleavan continued to make some of the more unpleasant sounds a tenor can make and still manage to create an appealing characterization that excused most, if not all, the barking and yelping. Most of the first two acts Watson seemed to holding back on the best part of her voice, its sheer formidable size, as if keeping a reserve for her monumental closing scene. In the event, her full power did not reveal itself even then, another factor that made the last 15 minutes of this five-hour extravaganza the least impressive section.

Front: John Treleaven (Siegfried), Back: Stacey Tappan (Woglinde), Ronnita Miller (Flosshilde), Lauren McNeese (Wellgunde) [Photo by Monika Rittershaus courtesy of the Los Angeles Opera]

Front: John Treleaven (Siegfried), Back: Stacey Tappan (Woglinde), Ronnita Miller (Flosshilde), Lauren McNeese (Wellgunde) [Photo by Monika Rittershaus courtesy of the Los Angeles Opera]

Eric Halfvarson triumphed as Hagen, his gruff, imposing bass as frightening as his portrayal. Freyer’s work here (with costumes designed by himself and his daughter Amanda) is emblematic of the Freyer approach. Hagen wore a bright yellow jacket, and around Halfvarson’s waist were two limp, yellow-clad dwarf legs, while the singer’s lower half was a pair of black trousers with white chalk streaks (matching some of other design elements). When Hagen stood behind his facade, he could drape the legs over the front, making him look truly troll-ish. At other times, though, Freyer had no hesitance about having the singer stride the stage, the dwarf-legs dangling feebly at his waist. This sort of staging element drove some attendees crazy, as Freyer quite obviously had no interest in naturalistic representation. For those accepting of this theatrical compromise, nothing distracted from the complete portrayal of Hagen as detailed in Wagner’s libretto — ugly, scheming, manipulative, and ultimately doomed.

Alan Held as Gunther and Jennifer Wilson as Gutrune both sang impressively from behind their blank, infantile Gibichung masks — masks that were able to make Siegfried’s deception when he kidnapped Brünnhilde plausibly staged, for once. Michelle DeYoung joined Jill Grove and Melissa Citro as the three Norns, and Ms. DeYoung also made for a fine Waltraute.

The pit reconfiguration did dampen the sound a bit too much as James Conlon continued to lead the Los Angeles Opera orchestra with finesse and power. The horns in particular had a great, great day on Sunday. There were a small number of departures from the audience after the first act, but most stayed, and then lingered to stand through the final ovations, which rose to a peak of volume when Conlon appeared. The conductor is truly becoming the heart and soul of Los Angeles Opera, which may save it come the day that Placido Domingo no longer leads — ostensibly — the company.

Not to say that Conlon is perfect. He managed to find the funding for his Recovered Voices series, which undoubtedly has brought some exposure to some interesting work — that of composers whose careers were crushed by the Nazis. However, opera being the expensive enterprise that it is, your reviewer can’t help but wonder if compromised stagings of these rare (for a reason, too often) operas really fits the managerial profile of a company that operates out of the Dorothy Chandler, a 3000+ seat hall. The last performance of Shreker’s Die Gezeichneten on a Thursday night saw a house with decent attendance but far from a sell-out. Conlon’s devotion to this music is evident in the power and beauty of the orchestra’s performance. Schreker’s score, however, sounded like a never-ending striving for sensual effects, with no solid lyrical themes as a foundation. The harmonic language tended to the sort of overripe modalities of the score to a Cecil B. De Mille Biblical extravaganza. Schreker’s libretto is even more hopeless, an incomprehensible mish-mash of perversion and political intrigue, mostly told through interminable dialogues with next to no action actually seen on stage.

Director Ian Judge had to work around the revolving platform built for Freyer’s production, and Judge found clever ways to exploit his limited resources, including some tasteful projection effects (designed by Wendall K. Harrington). An interesting cast tried their best, with Robert Brubaker outstanding as Alviana Salvago, the hump-backed dwarf who searches hopelessly for love while finding ample opportunities for sexual degradation. Anja Kampe sounded great as Carlotta Nardi, Salvago’s obsession. A huge cast of other able singers strode on and off but your reviewer could not make sense of their motivations and stopped caring by the end of the second act. Even an orgy in an island grotto couldn’t make him linger.

At least partly due to the cost of the Freyer Ring, next season there will only be six main stage opera productions, and the Recovered Voices series will take a hiatus. Perhaps future ventures in the series should be staged in some alternative, more intimate home, where those who share Conlon’s passion for this niche can settle in comfortably for their dose of early 20th century Viennese perversity and pretentiousness.

Chris Mullins

image=http://www.operatoday.com/StigmatizedLAO.gif imagedescription=Martin Gantner (Count Tamare), Anja Kampe (Carlotta) in The Stigmatized [Photo by Robert Millard courtesy of the Los Angeles Opera]

product=yes producttitle=Richard Wagner: Götterdämmerung; Franz Schreker: The Stigmatized productby=Los Angeles Opera. Click here for production and cast information. product_id=Above: Martin Gantner (Count Tamare), Anja Kampe (Carlotta) in The Stigmatized [Photo by Robert Millard courtesy of the Los Angeles Opera]

New ‘Figaro’ sparkling, beautiful

By John Coulbourn [QMI Agency, 26 April 2010]

As anyone who has ever enjoyed either Pierre Beaumarchais’ classic comedy or Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s opera buffa adaptation of his play can tell you, The Marriage of Figaro is not exactly a marriage made in heaven.

Alan Rich, Los Angeles Music Critic, Dies at 85

By Allan Kozinn [NY Times, 26 April 2010]

Alan Rich, a critic whose eloquent and passionate writing about classical music in both New York and Los Angeles made him an important voice in the American musical world over a long career, died on Friday at his home in West Los Angeles. He was 85.

April 24, 2010

HAHN: Le Marchand de Venise

Music composed by Reynaldo Hahn to a libretto by Miguel Zamacoïs after William Shakespeare’s play of the same name.

First Performance: 25 March 1935, Paris Opéra

Cast:

Antonio — a merchant from Venice; Christian

Bassanio — Antonio’s friend, in love with Portia; Christian

Gratiano, Salanio, Salarino, Salerio — friends of Antonio and Bassanio;

Christian

Lorenzo — friend of Antonio and Bassanio, in love with Jessica;

Christian

Portia — a rich heiress

Nerissa — Portia’s waiting-maid

Balthazar — a servant of Portia

Stephano — a servant of Portia

Shylock– a rich Jew, father of Jessica.

Tubal — a Jew; Shylock’s friend

Jessica — Daughter of Shylock, in love with Lorenzo; Jewess, converts to

Christianity

Launcelot Gobbo — a foolish man in the service of Shylock

Old Gobbo — the father of Launcelot

Leonardo — servant to Bassanio

Duke of Venice — Venetian authority who presides over the case of

Shylock’s bond

Prince of Morocco — suitor to Portia

Prince of Aragon — suitor to Portia

Magnificoes of Venice, officers of the Court of Justice, Gaoler, servants to

Portia, and other Attendants

Synopsis of Play:

Bassanio, a young Venetian, of noble rank but having squandered his estate, wishes to travel to Belmont to woo the beautiful and wealthy heiress Portia. He approaches his friend Antonio, a wealthy and generous merchant, who has previously and repeatedly bailed him out, for three thousand ducats needed to subsidize his traveling expenditures as a suitor for three months. Antonio agrees, but he is cash-poor; his ships and merchandise are busy at sea. He promises to cover a bond if Bassanio can find a lender, so Bassanio turns to the Jewish moneylender Shylock and names Antonio as the loan’s guarantor.

Shylock hates Antonio, both because he is a Christian and because he insulted and spat on Shylock for being a Jew. Also, Antonio undermines Shylock’s moneylending business by lending money at zero interest. Shylock proposes a condition for the loan: if Antonio is unable to repay it at the specified date, he may take a pound of Antonio’s flesh. Bassanio does not want Antonio to accept such a risky condition; Antonio is surprised by what he sees as the moneylender’s generosity (no “usance” — interest — is asked for), and he signs the contract. With money at hand, Bassanio leaves for Belmont with his friend Gratiano, who has asked to accompany him. Gratiano is a likeable young man, but is often flippant, overly talkative, and tactless. Bassanio warns his companion to exercise self-control, and the two leave for Belmont and Portia.

Meanwhile in Belmont, Portia is awash with suitors. Her father has left a will stipulating each of her suitors must choose correctly from one of three caskets — one each of gold, silver, and lead — before he could win Portia’s hand. In order to be granted an opportunity to marry Portia, each suitor must agree in advance to live out his life as a bachelor if he loses the contest. The suitor who correctly looks past the outward appearance of the caskets will find Portia’s portrait inside and win her hand.

The first suitor, the luxury and money-obsessed Prince Of Morocco, reasons to choose the gold casket, because lead proclaims “Choose me and risk hazard”, and he has no wish to risk everything for lead, and the silver’s “Choose me and get what you deserve” sounds like an invitation to be tortured, but “Choose me and get what all men desire” all but spells it out that he that chooses gold will get Portia, as what all men desire is Portia. Inside the casket are a few gold coins and a skull with a scroll containing the famous verse All that glitters is not gold / Often have you heard that told / Many a man his life hath sold But my outside to behold / Gilded tombs do worms enfold / Had you been as wise as bold, Young in limbs, in judgment old / Your answer had not been inscroll’d: /Fare you well; your suit is cold. His judgment captured by outward appearances, he is an unfit suitor for Portia and his bachelor life begins.

The second suitor is the conceited Prince Of Aragon. He decides not to choose lead, because it is so common, and will not choose gold because he will then get what many men desire and wants to be distinguished from the barbarous multitudes. He decides to choose silver, because the silver casket proclaims “Choose Me And Get What You Deserve”, which he imagines must be something great, because he egotistically imagines himself as great. Inside the casket, however, is the picture of a court jester’s head on a baton and remarks “What? A grinning idiot? Did deserve no more than this?” The scroll reads: Some there be that shadows kiss/Some have but a shadow’s Bliss/Take what wife you will to bed/I will ever be your Head — meaning that he was foolish to imagine that a pompous man like him could ever be a fit husband for Portia, and that he was always a fool, he always will be a fool, and the fact that he chose the silver casket is mere proof that he is a fool.

The last suitor is Bassanio. He realizes that the line “who chooseth me must give and hazard all he hath” could be a reference to the fact that marriage is a tremendous gamble and could mean a drastic turning point in one’s life, and chooses lead. The speech he gives before opening the leaden casket proclaims “So may the outward shows be least themselves. The world is still deceived with ornmament.” Before choosing the least valuable, ostentatious, and meager metal, Bassanio, proclaims “thy paleness moves me more than eloquence and here choose I joy be the consequence.” He makes the right choice.

At Venice, Antonio’s ships are reported lost at sea. This leaves him unable to satisfy the bond (in financial language, insolvent). Shylock is even more determined to exact revenge from Christians after his daughter Jessica flees his home to convert to Christianity and elope with Lorenzo, taking a substantial amount of Shylock’s wealth with her, as well as a turquoise ring which was a gift to Shylock from his late wife, Leah. Shylock has Antonio arrested and brought before court.

At Belmont, Portia and Bassanio have just been married, as have Gratiano and Portia’s handmaid Nerissa. Bassanio receives a letter telling him that Antonio has defaulted on his loan from Shylock. Shocked, Bassanio and Gratiano leave for Venice immediately, with money from Portia, to save Antonio’s life by offering the money to Shylock. Unknown to Bassanio and Gratiano, Portia has sent her servant, Balthazar, to seek the counsel of Portia’s cousin, Bellario, a lawyer, at Padua.

The climax of the play comes in the court of the Duke of Venice. Shylock refuses Bassanio’s offer of 6,000 ducats, twice the amount of the loan. He demands his pound of flesh from Antonio. The Duke, wishing to save Antonio but unwilling to set a dangerous legal precedent of nullifying a contract, refers the case to a visitor who introduces himself as Balthazar, a young male “doctor of the law”, bearing a letter of recommendation to the Duke from the learned lawyer Bellario. The “doctor” is actually Portia in disguise, and the “law clerk” who accompanies her is actually Nerissa, also in disguise. Portia, as “Balthazar”, asks Shylock to show mercy in a famous speech (The quality of mercy is not strained—IV,i,185, arguing for debt relief), but Shylock refuses. Thus the court must allow Shylock to extract the pound of flesh. Shylock tells Antonio to “prepare”. At that very moment, Portia points out a flaw in the contract (see quibble): the bond only allows Shylock to remove the flesh, not the “blood”, of Antonio. Thus, if Shylock were to shed any drop of Antonio’s blood, his “lands and goods” would be forfeited under Venetian laws.

Defeated, Shylock concedes to accepting Bassanio’s offer of money for the defaulted bond, but Portia prevents him from taking the money on the ground that he has already refused it. She then cites a law under which Shylock, as a Jew and therefore an “alien”, having attempted to take the life of a citizen, has forfeited his property, half to the government and half to Antonio, leaving his life at the mercy of the Duke. The Duke immediately pardons Shylock’s life. Antonio asks for his share “in use” (that is, reserving the principal amount while taking only the income) until Shylock’s death, when the principal will be given to Lorenzo and Jessica. At Antonio’s request, the Duke grants remission of the state’s half of forfeiture, but in return, Shylock is forced to convert to Christianity and to make a will (or “deed of gift”) bequeathing his entire estate to Lorenzo and Jessica (IV,i).

Bassanio does not recognize his disguised wife, but offers to give a present to the supposed lawyer. First she declines, but after he insists, Portia requests his ring and his gloves. He parts with his gloves without a second thought, but gives the ring only after much persuasion from Antonio, as earlier in the play he promised his wife never to lose, sell or give it. Nerissa, as the lawyer’s clerk, also succeeds in likewise retrieving her ring from Gratiano, who does not see through her disguise.

At Belmont, Portia and Nerissa taunt and pretend to accuse their husbands before revealing they were really the lawyer and his clerk in disguise (V). After all the other characters make amends, all ends happily (except for Shylock) as Antonio learns from Portia that three of his ships were not stranded and have returned safely after all.

[Synopsis source: Wikipedia]

Click here for the complete text of the play. image=http://www.operatoday.com/Sully.Portia.png image_description=Thomas Sully. Portia and Shylock, 1835. audio=yes first_audio_name=Reynaldo Hahn: Le Marchand de Venise first_audio_link=http://www.operatoday.com/Merchant.m3u product=yes product_title=Reynaldo Hahn: Le Marchand de Venise product_by=Porti: Michele Command; Nerissa: Annick Dutertre; Jessica: Eliane Lublin; Shylock: Christian Poulizac; Bassanio: Armand Arapian; Antonio: Marc Vento; Gratiano: Leonard Pezzino; Lorenzo: Tibere Raffali; Tubal: Jean-Louis Soumagnas; Le Prince d’Aragon: Jean Dupouy; Le Prince du Maroc/Le Doge: Pierre Nequecaur; Le Masque/La Voix: Christian Jean; L’Audencier: Lucien Dallemand; Grand Venise: Alain Charles; 1st Venetien: Michel Maranpuis; 2nd Venetien: Michel Cadiou; 1st Juif: Jean Jusconte; 2nd Juif: Robert Paleque; 3rd Juif: Jean Degarras; Un Serviteur: Michel Taverne; Salarino: Henri Pichon. Choeurs et Orchestre du Theatre National de L’Opera. Direction: Manuel Rosenthal. Paris 1978Shadowboxer, the opera

Opera Today is pleased to publish reviews of this work by five students of Dr. Olga Haldey, a frequent contributor to this site. Each of these reviews provides a unique perspective on the merits of the work and its performance. These reviews are:

- Shadowboxer — The Inner Life of Joe Louis by Jessica Abbazio

- A “CNN Opera” — Shadowboxer at UMD by Kelly Butler

- A “CNN Opera” — Shadowboxer at UMD by Kelly Butler

- Shadowboxer — The Rise and Fall of an American Hero by John Devlin

- Shadowboxer’s Left Jab by Deborah Thurlow

- Shadowboxer — A Tormented Joe Louis by Kate Weber-Petrova

Opera Today congratulates each of these writers and, of course, Dr. Haldey in affording them with an important educational opportunity. Writing about music generally, and opera in particular, is difficult because its essential task is to translate the language of music and to describe the elements of the theatrical experience into words that are meaningful to the reader. Critical reception of music, moreover, significantly shapes the cultural discourse. The teaching of informed critical writing, then, goes far in influencing our aesthetic values in the present and over time.

Additional details regarding this production may be found here.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/joe_louis.png image_description=Joe LouisShadowboxer — A Tormented Joe Louis

Directed by Leon Major and authored by librettist John Chenault and composer Frank Proto, this work will capture the imagination of opera lovers and sports fans alike.

Shadowboxer tells the story of Joe Louis, the African-American boxing legend who held the heavyweight boxing title from 1937 until 1949. Despite widespread racism in the United States during this period, Louis became a national hero. In his fights against German boxer Max Schmelling in particular, Louis’s life in the ring came to symbolize the larger political struggle between democracy and Nazism that was central to World War II. Thus many Americans tuned in to Louis’s fights in hopes that his victory in the ring could also signal a political and ideological victory for America and the Allies. His story came to symbolize something greater than one man’s journey, and the far-reaching significance of his life was what first captured the imagination of Maryland Opera Studio’s Artistic Director Leon Major.

Ask Major about the genesis of Shadowboxer, and he will inevitably recount his childhood memories of the famous 1938 rematch between Louis and Schmelling, during which Louis scored a knockout in the first round. Thus his fascination with Louis dates back many years. In fact, Major had been toying with the idea of an opera based upon the life of Louis for over two decades before approaching John Chenault and Frank Proto. Their creative collaboration spanned a period of roughly two years, and culminated with a series of performances at the Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center that began on April 17th and runs through April 25th.

Though Shadowboxer is based upon the life of a boxing legend, it is not confined to the boxing ring. Rather, it is a psychological drama that takes place in the landscape of Joe Louis’s mind. During the final moments of his life at his Las Vegas home, an elderly Louis is forced to confront a barrage of vivid and painful memories that become increasingly fragmented and incoherent as death draws near. The opera is a portrait of Louis’s final moments and the nightmarish fantasies that he must grapple with as he reflects upon his trials, triumphs, and failures. Chenault transforms the life of this American hero into a sweeping tale of human struggle, victory and defeat, suffering and joy.

The musical score of Shadowboxer is equally broad in its scope. Frank Proto drew upon his decades of experience as a composer and performer of classical music, jazz, and even Broadway show tunes to create a musical language that is as multifaceted as his musical background. Far from being a stylistic hodgepodge, however, Proto’s score captures the phantasmagoric nature of Louis’s consciousness and is an apt musical counterpart to the drama onstage. Shifting between a dissonant 21st-century idiom and a jazz-infused style that draws inspiration from American popular music of the 1930s and 40s, Proto’s score reflects the sounds of Louis’s heyday as they would be remembered in the murky recesses of the boxer’s deteriorating mind. Under the direction of conductor Timothy Long, the singers and instrumentalists of the University of Maryland give a compelling performance of Proto’s imaginative score.

The opera’s intriguing storyline and music should be enough to arouse curiosity in most music and sports lovers, but for those who are still not inspired to swing by the Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center this weekend, Major’s staging of the production should provide further incentive. Major does not simply approach Shadowboxer using a traditional arsenal of production tools. Rather, he considers how the cinematic and visual “literacy” of today’s audience members make them particularly receptive to the use of multimedia technologies in the performing arts, and he incorporates those technologies with a discerning eye. Multimedia designers Kirby Malone and Gail Scott White join forces with scenic designer Erhard Rom, lighting designer Nancy Schertler, and costume designer David Roberts to create a synthesis between classic production techniques and modern technologies.

Rom’s deconstructed stage design functions as the ideal backdrop for Schertler’s expressive lighting, which is used to convey the variegated landscape of Joe’s mind. At times, Schertler spatters the stage with dispersed beams of light and shadow, which serve as a visual counterpart to Louis’s fractured memory. During other scenes, she envelops the stage in suffocating ashen shades that — combined with grey costumes and a choir of masked faces––project Louis’s isolation and confusion as he sifts through hazy memories and painful emotions. Especially memorable is the scene in which Louis’s wife Marva sings her heart-wrenching aria “I love the man who isn’t there” immediately after handing her husband divorce papers. Schertler captures the mental anguish of both characters by bathing the stage in an eerie red glow. As Marva sings over martial rhythms played by the orchestra, her towering shadow looms above Louis, a devastating reminder of the torment he caused her by his womanizing lifestyle.

The asymmetric shapes and contoured screens of Rom’s stage design also pair well with the digital projections of Malone and Scott White. Avoiding naturalistic backdrops in favor of expressive abstractions, Malone and Scott White create a living world of action onstage. Their projections function as settings, dreamscapes, and reflections of Louis’s mind. Cloudy images of black and white shadows communicate Louis’s mental confusion and muddled memory, whereas projected details of the boxing ring set the scene, without suggesting a concrete reality. Photographs and newspaper headlines from Louis’s fights in the years leading up to World War II are juxtaposed with scenes of the raging war in Europe, thereby indicating how his victories in the ring were perceived as political and ideological triumphs. In this manner, the projections become characters in their own right, commenting upon the action and communicating the far-reaching implications of Louis’s life in the ring.

Such incorporation of modern technologies in opera is likely to make most traditionalists uneasy, but Malone and Scott White leave no doubt as to their artistic integrity. Their incorporation of new media not only enhances the psychological drama onstage, but also helps to make the production contemporary and relevant to a 21st-century audience.

Finally, we turn our attention to those artists who breathe life into the score and libretto of Shadowboxer, the performers themselves. Composed primarily of singers from the Maryland Opera Studio, this cast of performers includes many vocalists who will likely have successful singing careers upon leaving the University of Maryland. This is certainly true of Jarrod Lee, whose portrayal of old Joe Louis is, without a doubt, the highlight of the show. With a rich baritone voice that seems to glide effortlessly through even the most demanding passages, Lee gives a performance that is both musically refined and poignantly acted. His sensitive portrayal of Louis is the crux of the show’s effectiveness as a psychological drama. University of Maryland faculty member Carmen Balthrop also gives a captivating performance and nearly steals the show with her stirring portrayal of Louis’s mother. Also noteworthy are Adrienne Webster (Marva Trotter, Louis’s wife) and VaShawn McIlwain (Jack Blackburn, Louis’s trainer), whose impressive vocal abilities are matched by their talent for dramatization. Less impressive is Duane Moody’s portrayal of young Joe Louis. Moody does not convincingly project the youthful vigor and tenacity of the heavyweight boxer. Furthermore, his performance emphasizes the boxing champion’s vices, but fails to effectively communicate his dignity and humanity.

In spite of this single shortcoming, Shadowboxer is well worth the trip to College Park, and one can only hope that its premiere at the University of Maryland will inspire future performances. In an era when opera must compete with mass consumerism and digital technologies, it is refreshing to see a new work that merges the performing arts with new media, and that explores timeless themes in more contemporary contexts.

Kate Weber-Petrova

University of Maryland

All photos by Cory Weaver/University of Maryland — College Park

Shadowboxer’s Left Jab

With music by Frank Proto and libretto by John Chenault, Shadowboxer culminated a twenty-five year old dream of MOS director Leon Major to bring Louis’s rags-to-riches-to-rags story to the opera house.

Longtime collaborators Proto and Chenault have written a challenging, provocative, and somewhat problematic work. It was skillfully produced, despite some writing flaws: Major and his MOS forces pulled out all the stops, with many saving effects that supported the sagging score. Chenault devised his libretto as a series of flashbacks the older Louis has after a heart attack. The main confusion arose with having three Joes onstage, often simultaneously. Older Louis watched as Young Joe (played by tenor Duane Moody) re-enacted his various flashbacks. Young Joe stood alongside older Joe during many scenes, mirroring his actions or even relating to him, and would blend in and out of the crowd. Two actors, playing Joe the Boxer (Nickolas Vaughn) and Joe’s Opponents (Craig Lawrence), mimed several of the famous boxing matches. The boxing actors brought to the stage the needed raw energy and passion raised during a fight. One wished for a single person to play Young Joe, who could also act the boxing scenes, or even one singer-actor throughout the show, rather than three. Luckily, Major imaginatively guided the interaction of the three Joes, so the confusion was less apparent.

Unfortunately, Chenault‘s solo lines for older Louis, which are certainly intended to be introspective, came across as rambling, and told rather than revealed the character’s thoughts. Proto’s angular musical lines did not aid these solo sections, but rather showed an accomplished instrumental composer struggling to set philosophical words. The result had too many moments of the older Louis singing challenging intervals, rather than well-crafted vocal lines setting a succinct script. Fortunately, Jarrod Lee (playing Old Joe) made music and drama out of the disjointed lines. What a relief near the end of Act II to hear Lee sing a real tune about life being beautiful!

Proto’s highly complex music includes a full pit orchestra, a 15-member singing cast and a choral ensemble, as well as the unique feature of an onstage jazz band. The jazz band adds the sound element of the era, not so much as period music, but as its musical descendant. Timothy Long expertly conducted the difficult score, and seemed quite at home directing the club-influenced method of throwing the tune back and forth between the band and the orchestra. Both ensembles played sensitively, and seemed at ease with the harmonic and rhythmic language of the score. When the full company was in action--reliving the fights or relating to each other--the entire production gleamed with energy.

Often wearing faceless, half-skull masks, the choral ensemble acted as a Greek chorus, singing Proto’s Swingle-Singer-influenced harmonies with confidence, and often, chilling beauty. They gave voice to Louis’s memories of the moment. Each singer sat or stood near a black chair, symbolically lifting it up, turning it on its side, or switching it to another angle to move in or out of the action. Some of the best music, and the most notable performances, came from three sets of trios surrounding Louis. (Need we mention the recurring jazz trio, or even trinity, theme pervading the script?) VaShawn Savoy McIlwain gave a strong, earthy, no-nonsense performance as trainer Jack Blackburn. Along with McIlwain, Robert King (Julian Black) and Benjamin Moore (John Roxborough) rounded out this strong trio of men guiding Louis’s career. The Three Reporters, representing the press (Andrew Owens, Andrew McLaughlin, and Colin Michael Brush), offered solid vocal harmonies and acted with appropriate slime as they either kept their racism in check or pounced on Louis when he lost. The Three Beauties, depicting the wide variety of Louis’s female companions and sung by Madeline Miskie, Amelia Davis, and Amanda Opuszynski, melted over both young and old Joe. Their supple voices blended well, often using a straight vocal tone more akin to musical theatre or jazz.

Strong lead performances were given by professor Carmen Balthrop, who portrayed Louis’s mother, Lillie Brooks, with inner dignity, and deep, maternal emotion; Adrienne Webster (Louis’s wife Marva Trotter), who gave herself completely to the role with powerful, emotional singing; and Peter Burroughs, who generated the necessary bravado for German boxer Max Schmeling. Jarrod Lee gave an outstanding performance as he embodied the aged and broken Louis. He sang nearly ninety-five percent of the opera wheeling around in a wheel chair. The logistics and energy of continuing that for two hours was a feat unto itself. Exhibiting excellent musicianship, he sang the difficult, angular vocal lines with a commanding, emotional baritone throughout the opera. Lee is certainly a singer to watch in the future.

Set designer Erhard Rom brought ringside flavor to his stage with an open floor, the moveable black chairs, and three angular screens suspended from the ceiling, hugging the up, left and right stage perimeter. Lighting, hung from crisscrossed girders, added to the angularity of the stage, the screens, and the musical lines. Spotlights were often boxing-ring square, rather than the customary round spots. Projection designers Kirby Malone and Gail Scott White chose images, such as boxing ring corners, old radios, and fight scenes, to enhance the subtext of the libretto. A memorable effect occurs in Act I: as the older Louis reminisces about various boxers, each boxer’s individual picture appears to fade in and out of a swirling fog on the left or right screens. Kirby and Malone added a moving-picture element several times when a photo would appear on each screen in sequence, as if it were a film. Often the cast sang against the actual film footage of scenes from World War II and boxing matches. This did not distract, but rather enhanced the words and mood with more of a background visual effect. Fight sound clips were also interspersed periodically. Near the end of Act II, Louis hears the voices of boxers Jack Johnson and Muhammad Ali speak to him through an onstage solo sax and trumpet. Their words flash on the screen as the instrumental voices “talk.” A tighter conversational script for Joe would have given the audience a better chance to imagine the other boxers’ words. As it was, the instrumentalists appearing onstage weakened the dramatic effect.

The life of boxer Joe Louis inspires sober reflection upon the realities of living in a racist society, then and now. Chenault featured this topic prominently, and appropriately, throughout the opera. Proto, Chenault and the entire MOS team have certainly fulfilled Major’s dream to show the life of “a man who boxed for a living.” They have launched another complex hero for the opera world to celebrate, and to contemplate.

Deborah Thurlow

University of Maryland

Shadowboxer — The Rise and Fall of an American Hero

That idea came to fulfillment this week at the University of Maryland’s Clarice Smith Center for the Performing Arts. Major, director of the Maryland Opera Studio, gave this reason for the project’s prolonged genesis: “I knew that I wanted to do an opera on the life of this great American hero. The question was—when would I find the right composer/librettist team to make this work?”

He found that team two years ago. Inspired by the work of Frank Proto, composer-in-residence of the Cincinnati Symphony, he called Proto to discuss the project. Soon afterward, Proto and his librettist partner, John Chenault, were commissioned to write Shadowboxer.

The project that then began to unfold was one of enormous complexity. The initial focus, however, was a simple question: Joe Louis the boxer was an American hero, but was Joe Louis the man equally heroic? This issue is the focal point of the opera and the most poignant element of the production. Major, Proto and Chenault force the audience to ask itself the question: does this man deserve my admiration, or even my respect?

It is a powerful question to ask. The opera does indeed pay tribute to the life of a noble man, a man whom Major, Proto and Chenault all view as a hero. But their portrayal of Louis shows a battered, broken and unstable invalid, confined to a wheelchair for the duration of the piece. In fact, the opera begins with Louis having a heart attack. It then flashes backward in time as a cast of figures from Louis’s fragmented memory drifts gradually in and out of focus. This device reveals Louis’s weakness, not his strength. He becomes a fallen hero as Major forces us to redefine our sense of what a hero really is.

Chenault uses a variety of figures to add this new dimension to the character. Similar to the way in which Alice Goodman reveals the human side of Richard Nixon in Nixon in China, Chenault wants to show the personal side of Joe. The man had friends, Chenault states, from “all strata of life. He knew royalty, but he also knew the shoeshine on the corner of the street.” In Shadowboxer, we see how these different influences profoundly affected Louis as we follow two main character groups.

The first comprises real people, all of whom were close to Louis: his trainer, Jack Blackburn; his agent, John Roxborough; his manager, Julian Black; his wife, Marva; and his mother, Lillie. These characters force Louis to confront the human element in his life—how his actions, fame, and fortune affect those around him. We witness the true love of his mother and of his wife, and the loyal support of his entourage.

In contrast, Chenault also includes a large chorus, composed partially of different groups of caricatures representing the types of people who had a negative impact on Louis. There are three beauties, all of whom successfully seduce Louis and abuse his famous generosity. There are also three fickle reporters who capitalize on both his successes and his failures.

The contrasting elements in Louis’s life are echoed in Proto’s score. The music to Shadowboxer is extraordinarily challenging. When the singers received their first version of piano-vocal scores over a year ago, questions were asked: “Will anyone know if I don’t sing the right notes?” and even more importantly, “What are the right notes?!”

These questions arose because the score is mostly atonal, resulting in vocal lines that are difficult for the singers to navigate, tune and memorize. Chorus members have the added challenge of having to hold their parts against those of their highly dissonant neighbors. These parts often enter on a pitch that is dissonant with the pitches already being sung, without the benefit of an aural cue from the orchestra. The singers not only meet these challenges, but are able, despite the atonal crunch, to create a canvas of haunting beauty. The dissonance that pervades the music adds to the portrayal of the nebulous nature of Louis’s mind.

Apart from the musical difficulties that result from learning an atonal opera, conductor Tim Long faced the additional challenge of having to coordinate the normal pit orchestra, soloists and chorus with an onstage jazz band, offstage chorus, and onstage jazz instrumentalists. A single conductor (even with multiple monitors projecting Long’s image to the singers, both on- and offstage) proved insufficient, so assistant conductor Michael Ingram was called upon to conduct the offstage groups. Ingram had to watch Long on a television monitor and conduct — with a glow stick, no less — ahead of that image, in order for the alignment to sound correctly in the hall. After many rehearsals spent perfecting the timing, these different musical elements combine to form a wonderful tapestry upon which the Louis story is told.

Several of the soloists deliver noteworthy performances that deserve special mention. Carmen Balthrop is captivating as Lillie, Louis’s mother. She sings a gripping aria about the pain of a mother watching her son do battle in the ring. With stunning emotional power, Adrienne Webster (Marva) captures the audience in a fiery aria chastising Louis’s promiscuity.

Jarrod Lee is superior in both his singing and acting as Old Joe, the most difficult role in the opera. He portrays the frail Louis who watches all of the action, interacting with the figures from his past as he floats from memory to memory. Never breaking his intense focus, Lee provides visceral reactions as he gains insight into his own life. Especially during the second act, a large musical burden is placed upon the Old Joe character. Lee navigates the difficult singing with masterful skill, and brings depth and honesty to the role.

Equally compelling are Major’s directorial decisions. He deals with the parallel time-frames of the opera in two significant and related ways. First, he keeps the chorus onstage at all times. This chorus includes the soloists who portray the opera’s other major characters. Second, Major masks all of the ensemble members; they unmask only to assume a solo role. These devices allow Major to deploy a larger chorus, have characters drift into and out of Louis’s mind in a fluid fashion, and keep the idea of each of these characters present throughout the work. In this way, Major is able to manipulate time, seamlessly integrating the present with scenes from Louis’s past. Major’s masked chorus is an excellent solution to a difficult problem, and creates a clear picture for the audience.

This chorus creates an especially memorable first scene when it is seated onstage and Louis wheels his way among its members. As Louis passes, the masked figures turn and lean towards him, then slowly re-center themselves after he moves away. This places Louis in a type of purgatory where he is held by spirits. The journey that we then begin with Louis becomes a necessary one for him to regain understanding in his life.

The chorus is the first of a series of successful visual elements in the opera. Costume designer David Roberts artfully dresses each character in varied shades of grey. The only color is found in Louis’s red-checkered bathrobe—a subtle and constant reminder that the action takes place in Louis’s memory. The set is also a unique design that allows for three hanging screens along the back of the stage. Throughout the opera, the screens reflect commentary on the action as relevant pictures and video are projected upon them. Projection designers Kirby Malone and Gail Scott White display flashes of newspaper headlines hailing Louis’s boxing exploits, quotes from his competitors that added edge to Louis’s competitive fire, and swirling smoke during periods where he fights to regain clarity of memory.

The use of projection is sparing, though sometimes too overt. For instance, at the end of the opening scene described above, each of the main characters stands and unmasks while his or her name is projected above. The resulting introduction of the protagonists feels forced, especially given that Chenault seamlessly weaves character introduction and plot development in the scenes that follow. The projections are most effective when they add to the liveliness of Louis’s post- fight celebrations by flashing news headlines and photos of revelers in Harlem.

Frank Proto and John Chenault’s Shadowboxer pursues a noble social goal. Like another modern opera, Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess, it explores the question of race; like Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth, it examines the citizen’s relationship to the state. But at its heart, Leon Major explains, “It is not an opera about a boxer; it is an opera about a man who makes his living as a boxer.” In Shadowboxer, we are provided with a transcendent view inside the mind of a great, and fallen, American hero.

John Devlin

University of Maryland

A “CNN Opera” — Shadowboxer at UMD

The unexpected subject matter, juxtaposing the seedy world of boxing with the sophistication of opera, is bound to raise a few eyebrows. However, it contains topics typically found in opera: love, betrayal, sex and scandal. Every aspect of the show – music, lighting, costumes, staging, and audio-visual effects – is carefully designed to create a story which takes place in the abstract reflections of Joe’s memory. The unique subject coupled with Leon Major’s brilliant staging, an exceptional production team, and a crew of fresh, young voices, provides an intriguing and gratifying night at the opera.

The libretto, created by John Chenault, is not just a chronological biography of Joe's life; the story begins just before Joe's death. Continually jumping through time, the opera explores moments of triumph and the moments where the protagonist allows his demons to prevail. Through the journey, we are introduced to three Joe's: Old Joe in a wheelchair (Jarrod Lee), young, vibrant Joe eager to tackle the world (Duane A. Moody), and boxing Joe for the fight scenes (Nickolas Vaughn). On the surface, clear racial tensions are addressed, but there is more to Joe's story than the trials and tribulations of an African-American trying to succeed in a white world. From Joe’s perspective, we witness his vulnerability to women, his issues with the IRS, and the unjust title of democratic symbol the US media placed upon Joe during World War II. This “CNN opera” is much like John Adam’s Nixon in China, in that we see the real Joe behind the media portrayal, allowing the audience to formulate their own perceptions of Joe Louis.